calsfoundation@cals.org

Little Rock (Pulaski County)

State Capital, County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 34º44’43″N 092º16’31″W |

| Elevation: | 350 feet |

| Area: | 120.05 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 202,591 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | November 7, 1831 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

2,167 |

3,727 |

12,380 |

13,138 |

25,874 |

38,307 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

45,941 |

65,142 |

81,679 |

88,039 |

102,213 |

107,813 |

132,483 |

159,151 |

175,795 |

183,133 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

193,524 |

202,591 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

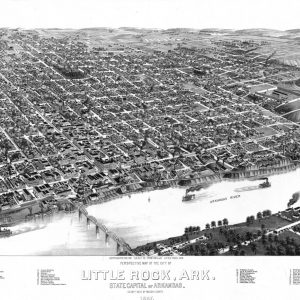

Little Rock, Arkansas’s capital city, is situated on the south bank of the Arkansas River near the geographic center of the state, making it a natural hub for commerce. In addition, the state’s three major landforms join within the city limits: the foothills that rise northwest to the Ozark Plateau, the Delta lands that extend east to the bank of the Mississippi River, and the rolling plains that stretch southwest into Texas. This confluence makes Little Rock a natural political center.

Pre-European Exploration

The Arkansas River Valley, including the location of “the little rock,” was claimed by the Quapaw when Europeans first explored the region. The Quapaw, members of a group of Dhegiha-Siouan-speaking tribes which also includes the Osage, resided in southeast Arkansas in the late seventeenth century and continued to live primarily along the Arkansas River until they were forced to leave in 1824. (Their designation as “Arkansea,” or“people of the south,” by Illinois tribes led to the name of the river and, ultimately, of the state.) Although no settlement or trading post is known to have existed precisely at “the little rock,” a community of mixed Quapaw-French families did live nearby from about 1790 to 1820, resulting in the designation of one of Little Rock’s oldest neighborhoods as the Quapaw Quarter.

European Exploration and Settlement

One of the first European explorers in the region, Jean-Baptiste Bénard de La Harpe, observed geological changes at the water’s edge in 1722. On April 9, he made note of “rocks sticking out of the ground,” referencing the first rock up the river, but he did not name it. La Harpe was more enthusiastic when it came to what he called the French Rock—“le Rocher Français”—the “bluff of mountainous rock” up the bend and north of the river, now called the Big Rock. The French called the smaller outcropping on the south bank “le Petit Rocher” (the little rock), with the name first showing up on a map in 1799.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

“The Rock” was included in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, but the first settlement near the landmark was not made until the spring of 1812 when a trapper named William Lewis built a cabin on the bank of the river about 100 yards north from where the Old Statehouse stands today. Lewis left that October but filed a pre-emption claim on the land at the Federal Land Office in Nashville, Tennessee. According to the British naturalist Thomas Nuttall, no one permanently settled at “The Rock” until the spring of 1820, when a group of men established a town at the site. In March of that year, a U.S. post office with the name “Little Rock” was established.

Land speculators, armed with Lewis’s pre-emption claims and New Madrid Certificates (from the New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811–1812), soon arrived on the scene to stake claims. New Madrid claimants renamed the town “Arkopolis” and began selling lots. In the midst of the chaos, the Arkansas territorial capital was scheduled to move to Little Rock on June 1, 1821. Disgruntled settlers disguised themselves as Indians to move buildings at night in support of their claims. In the end, the claims were ruled invalid as the Quapaw had not ceded the land at “The Rock” until 1818, and a compromise was reached. The name changed back to Little Rock, and in the fall of 1821, the Arkansas territorial capital was moved there from Arkansas Post. Little Rock was incorporated as a town in 1831 and as a city in 1835.

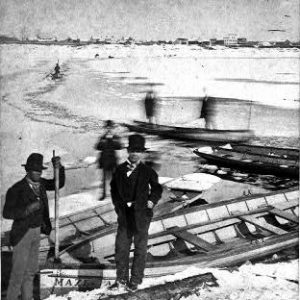

The Eagle was the first steamboat to navigate up the Arkansas River to Little Rock, arriving on March 16, 1822.

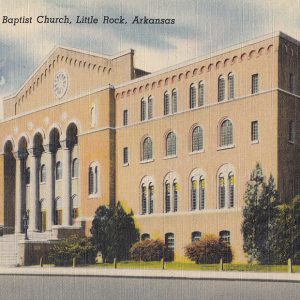

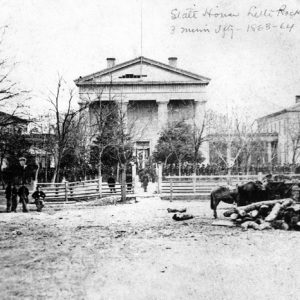

The Old Statehouse at Markham and Center was started in 1833 and completed in 1842. In the meantime, Arkansas was admitted to the Union as a slave state on June 15, 1836. Religious services for both enslaved persons and Free Blacks were provided by First Negro Baptist Church, founded in 1845 and later known as First Missionary Baptist Church. Free schools for white boys and girls started in Little Rock in the 1853. Gas lighting came to Little Rock in 1860, followed by the telegraph in 1861, just in time to report the early battles of the Civil War. Arkansas reacted to the news and seceded from the Union on May 6, 1861. Even before the state seceded, the Little Rock Arsenal had been seized by volunteers from several counties to prevent it from falling under federal control.

Civil War through Reconstruction

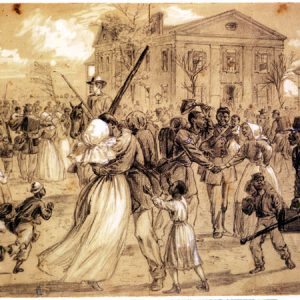

During the war, activity in Little Rock ground to a halt. When the Confederate army departed Arkansas and went across the Mississippi River in April 1862, the state was left undefended. Union troops feinted as close to Little Rock as Searcy (White County), fifty miles away, and the state government was hastily removed to Hot Springs (Garland County) for a few weeks. Between 1863 and 1865, both Confederate and Union forces constructed fortifications to protect Little Rock; Confederates concentrated efforts on the north side of the river, while Union efforts were built south of the city.

In 1863, Union troops skirmished along the north side of the Arkansas River as a diversion but put up a pontoon bridge nine miles south of the city on the morning of September 10 and, after a few shots, occupied Little Rock by 4:30 that afternoon. The Confederate capital was permanently removed to Washington (Hempstead County), while a provisional Unionist government was set up at Little Rock. A minor skirmish at Little Rock in late 1864 provided Union forces with further intelligence. At the end of the war, Little Rock, which had a population of 3,727 in 1860, built a cemetery on Confederate Boulevard (now Springer Street) to inter the remains of 2,000 Confederate and 2,000 Union soldiers.

Held in 1865 in Little Rock, the Convention of Colored Citizens united African Americans in the state with the goals of protecting their newly granted emancipation and advocating for greater civil rights, such as suffrage and education.

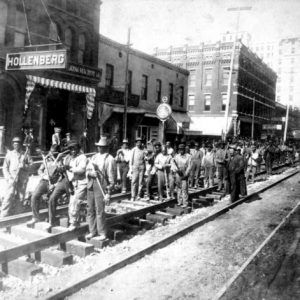

In 1873, during Reconstruction, the railroad finally reached Little Rock with the building of the Baring Cross Bridge at the foot of Cross Street.

In 1874, the city experienced a local war known as the Brooks-Baxter War when Republican Joseph Brooks seized the Old State House as governor after the courts declared him elected over Elisha Baxter. A cannon named “Lady Baxter” was placed on the lawn of the Old Statehouse, and both sides called up troops. Governor Baxter appealed to President Ulysses S. Grant. U.S. troops were moved from the Little Rock Arsenal to downtown on April 20, 1874. A special session of the legislature was called for May 11, 1874, which confirmed Baxter as governor, and Brooks withdrew. There were about 200 men killed in the confrontation.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

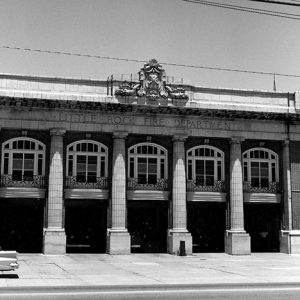

Both the University of Arkansas School of Medicine (now the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences) and the first telephone exchange opened in Little Rock in 1879. The short-lived Little Rock University opened in 1882; its buildings were eventually taken over by Maddox Seminary, also short-lived. Electric service was introduced in 1883, and in 1887, the first streets in Little Rock were paved with cobblestone. This is also the year the first sewer lines were laid. The Little Rock Fire Department started in 1892. The M. M. Cohn department store was relocated to Little Rock after being founded in Arkadelphia (Clark County) in 1874 and quickly became an established firm, lasting more than a century.

In 1888, three women started a women’s weekly newspaper, Woman’s Chronicle, that ran through 1893; one of its primary focuses was suffrage for white women.

In 1892, Henry James was lynched for the alleged sexual assault of a young child. When Governor James Phillip Eagle attempted to take action against one of the shooters, the mob turned on him.

In 1893, in exchange for property atop Big Rock, the U.S. government deeded the arsenal at 9th and Ferry to the city. This building was the birthplace of General Douglas MacArthur, and it and the surrounding grounds have been named MacArthur Park in his honor. Opened in 1885, West End Park encompassed a six-block area between 14th and 16th Streets and Park and Jones (formerly Kramer Street). By the late 1920s, much of the land had become the site of what is now Central High School. In 1897, the “Free Bridge,” the first non-railroad bridge, was built across the Arkansas River connecting Little Rock with its Eighth Ward, modern-day North Little Rock (Pulaski County).

Early Twentieth Century

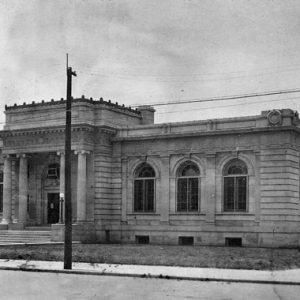

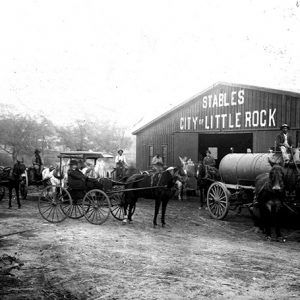

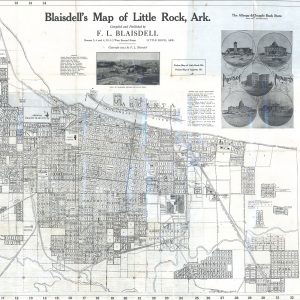

Construction of the Arkansas State Capitol, at the head of Capitol Avenue, was started in 1899 and finished in 1914, the same year the Rotary Club of Little Rock was established. Intra-urban streetcars had been operating in Little Rock since the 1870s, but not until 1902 was the Little Rock Railway & Electric Company (LRREC) firmly established. In 1903, the city decreed segregation on city streetcars (Jim Crow segregation lasted into the 1960s), and the 3rd Street viaduct was built across railroad tracks west of the city, opening the way westward to the town of Pulaski Heights, which was annexed in 1916. Also in 1903, Little Rock’s Eighth Ward on the north side of the Arkansas River, in a legal maneuver, voted to secede from Little Rock by annexing itself to the newly formed town of North Little Rock. The present City Hall at Markham and Broadway was completed in 1908.

Progressive candidate Charles Edward Taylor took the office of mayor in April 1911 and sought to tackle the problems of vice and sanitation in the city. The Little Rock Censor Board formed in 1911 for the purpose of regulating entertainment based on moral judgments, and Taylor also worked to shut down known “houses of ill repute” such as those in the districts colloquially known as “Battle Row” and “Fighting Alley.” Municipal garbage collection started in 1912.

The Picric Acid Plant built outside Little Rock in 1918 was a munitions plant that produced the highly explosive chemical picric acid for use during World War I. It was one of only three federal facilities in the United States.

Little Rock’s airport had its beginning in 1917, during World War I, when the federal government acquired forty acres for a field. An aviation supply depot was also constructed during World War I, in 1918. It closed in the early 1920s. In 1930, Little Rock purchased the field and, in 1942, named it Adams Field for Captain George Adams of the Air National Guard, who was killed there when his airplane’s propeller assembly exploded.

Little Rock’s first skyscraper, a ten-story building known as the Southern Trust Building opened in 1907. The city’s first radio station, WSV, began broadcasting in April 1922. The Missouri Pacific Hospital was established in 1925, and the following year Velvatex College of Beauty Culture, then the state’s only approved beauty school for people of color, was incorporated.

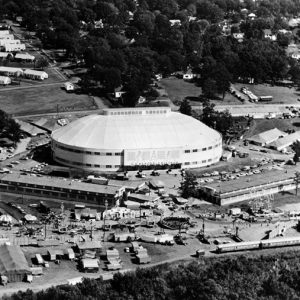

The Little Rock Zoo started by chance. After the 1926 state fair closed at Fair Park (now War Memorial Park at Markham and Fair Park), city officials found a number of abandoned animals left on the grounds. Pens were built to keep the creatures and then, in the 1930s, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) erected the rock buildings that are still a part of today’s zoo.

October 1, 1927 was declared Charles Lindbergh Day after the famous pilot landed in Little Rock as part of a larger tour. The Little Rock parade was attended by 75,000 people, after which Lindberg gave a speech celebrating advances in aviation.

The Flood of 1927 washed away part of the Baring Cross Bridge. That same year, the new Little Rock Senior High School at 14th and Park (now Central High School) opened in time for the fall semester. College classes that were offered on the second floor of the new high school later moved to a site at State Street between 13th and present-day Daisy L. Gatson Bates Drive, which was named Little Rock Junior College.

For the first half of the twentieth century, West 9th Street was an African-American city within a city, with black businesses, churches, banks, and social halls located along the street. It was anchored at 9th and Broadway by the three-story national headquarters of the Mosaic Templars of America (MTA), a black fraternal organization dating from 1883 that provided insurance and other services to African Americans in twenty-six states during an era when few aids were available to minorities. This intersection and surrounding neighborhood area saw horrible violence in 1927 when John Carter was lynched and his body was desecrated in the midst of three hours of rioting which had to be stopped by the Arkansas National Guard. The Mosaic Templars ended in receivership in 1930 due to a sharp decline in premium revenue at the start of the Great Depression. Though much of 9th Street no longer resembles what it had once been, the Mosaic Templars has been reconstructed as a museum of African-American history.

Ray Winder Field, first known as Travelers Field, opened in 1932 and served as the home to the Arkansas Travelers off and on until its demolition in 2012.

Little Rock hosted the national United Confederate Veterans Reunion for the years of 1911, 1928, and 1949.

Beginning as early as 1915 but continuing on through the 1970s, blockbusting was a technique used by realtors to convince white people to sell their homes by threatening that the area might soon also be home to African Americans. Little Rock, being the most urban area in the state, experienced this more than other Arkansas communities, with neighborhoods like Pine Forest and Oak Forest being targeted by blockbusters.

World War II through the Faubus Era

Because of war in Europe, Camp Robinson, located northwest of North Little Rock and called Camp Pike during World War I, was reactivated in September 1940 as a cantonment for 50,000 soldiers. Its presence resulted in a severe housing shortage in Little Rock, which was rectified by the building of Cammack Village as a suburb during 1941–1943 to provide homes for the families of army officers based at the camp.

Shortly after the war, Timex and Westinghouse opened factories in Little Rock. On December 17, 1945, most of the employees of the Southern Cotton Oil Mill went on strike. The strike remained peaceful until December 26, when a strikebreaker killed one of the striking workers. However, rather than charging the murderer, local authorities charged five strikers under the state’s Anti-Labor Violence Act of 1943, which make strikers criminally liable for any violence that occurred during such a labor action. The legal struggle that continued for more than seven years helped to realign traditional Arkansas politics.

Little Rock’s first TV station, the 100-watt UHF Channel 17 KRTV, began telecasting in April 1953. KATV started operation in December of that year. The first modern shopping center in Little Rock, the Town and Country Center at Asher and University, was built in 1956. Also in 1956, KOKY, Little Rock’s first radio station staffed by and aimed toward African Americans, was founded. It later moved to Sherwood (Pulaski County).

In 1957, the curriculum at Little Rock Junior College was expanded to four years, and the school operated on a new campus at 28th and University Avenue as Little Rock University until 1969, when it merged with the University of Arkansas system as the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UA Little Rock).

In the fall of 1957, the Little Rock School District started an approved integration plan at Central High School. There was local opposition, and Governor Orval Faubus “interposed” himself between federal decrees and Central High School by calling out Arkansas National Guard units to prevent integration of the school. The federal government ordered the 101st Airborne Division to Little Rock, and under the guard of federal troops, integration at Central proceeded. However, in a vote held the next spring, Little Rock voters chose to close Little Rock high schools for the 1958–59 school year. This was soon perceived as a mistake, and all the city high schools were reopened in 1959 as integrated schools, though many white families, as a result, moved their children to private or suburban schools. The Labor Day Bombings of 1959 was one of the last highly visible attempts against these progressive changes.

In November 1957, citizens of Little Rock voted to change from a mayor-alderman city government to a city manager–board of directors form of governance. This change had been promoted by the Good Government Committee, an confederacy of local business elites opposed to the coalition of trade unionists an African Americans that had elected Woodrow Wilson Mann mayor.

Water for Little Rock was originally drawn from sources such as the Arkansas River, wells, and a lake in Saline County. In 1958, construction of Lake Maumelle on Arkansas Highway 10 was completed, and the city had a source of clean water. However, as the city expanded westward, residential developers began buying land around the lake, and there is now a contentious debate about residential developments near the lake because of possible pollution caused by lawn fertilizers and other factors related to developed land.

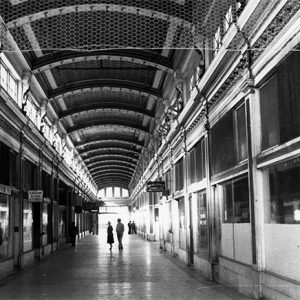

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform

In 1962, an urban renewal program in Little Rock did away with many of the stores on Main Street, and in 1964, the Quapaw Quarter Historic District was formed to save the old homes on the east side of town. (Urban renewal had already extinguished the predominately Black community of West Rock.) In 1977, in an effort to save downtown, Main Street was closed to vehicular traffic and made into a pedestrian mall. A half-block shopping mall, the Main Street Mall, opened in 1987, but continuing efforts to popularize a traffic-free downtown failed, and a redesigned Main Street was opened again to vehicular traffic in 1991.

Interstate 630, Little Rock’s major east-west expressway, was started in the 1960s as the 8th Street Expressway but was later added to the interstate system as I-630. It was completed in 1977 and, in 1990, opened the way to Chenal Valley, 7,000 acres of land recently annexed to the western edge of Little Rock. Chenal Valley contains some of the city’s newest and most exclusive suburbs. The construction of this interstate contributed to—and reflected—the racial divides happening in the city. During the 1980s, Little Rock experienced significant white flight, with white people leaving racially mixed downtown areas for suburban areas in western Little Rock or neighboring cities. Later in the 1980s, a group of citizen activists launched the “Save the River Parks” campaign to prevent the construction of a highway along the southern bank of the Arkansas River.

Little Rock’s modern port, with its own 1,500-acre industrial park and shortline railroad, went into operation in 1969, only months after the McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System made the Arkansas River navigable up to Little Rock. Also in 1969, Little Rock voters approved restaurants serving mixed drinks to the public, opening the door to increased convention business.

The Little Rock Uprising of 1968 took place in response to the questionable death of a young black man in the penal system. What began as a peaceful march and rally turned confrontational and mounted into violence for several days, including several acts of arson. In 1974, Little Rock hosted the second National Black Political Convention.

In 1973 Little Rock annexed an area which included Mabelvale (Pulaski County), while Pankey (Pulaski County) was annexed in 1979. A flood in 1978 killed ten due to outdated drainage systems.

The present terminal at the Little Rock National Airport was built in 1972. In 1973, a small company named Federal Express (FedEx), located at the airport, requested an increase in the length of a landing strip and construction of a second. The airport commission refused, so FedEx moved to Memphis that year. The airport has since been greatly expanded and now covers 1,350 acres.

Meanwhile, the city purchased railroad land along the south bank of the river from the Baring Cross Bridge to the Junction Bridge and cleared tracks. In May 1983, the Julius Breckling Riverfront Park was opened just in time for that summer’s Riverfest. Buildings along East Markham (now President Clinton Avenue) were cleared, and the River Market District came into being in 1996.

The Arkansas Women’s Training Project (AWTP) started in 1980 in Eureka Springs (Carroll County) and relocated in 1982 to Little Rock; it incorporated as the Women’s Project in 1985. The feminist, anti-racist organization aims to eliminate systemic sexism and racism and has worked all over the state to help women and families.

With the takeover of the Arkansas Gazette by the Arkansas Democrat in 1991, creating the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Little Rock became home to Arkansas’s only daily statewide newspaper. In the wake of this, the magazine Arkansas Times converted to an alternative weekly, which ran through 2018, before converting back into a glossy magazine. The alternative newspaper Little Rock Free Press was started in 1993 by Dottie Oliver, and ran until 2005, when it began statewide circulation and became Arkansas Free Press. It continues today as an online publication.

On March 1, 1997, there was a tornado outbreak that was one of the deadliest in the state. Sixteen tornadoes were produced by four supercell thunderstorms, four of which caused the outbreak’s twenty-five fatalities.

In 2004, a “River Rail” streetcar line was put into operation to connect Little Rock’s River Market District with North Little Rock’s downtown. In 2007, River Rail service was extended to the William J. Clinton Presidential Center and Park and the Heifer International world headquarters.

The Little Rock Marathon has run annually since 2003.

The USS Little Rock (LCS-9), the second ship to be named for the city, officially joined the U.S. Navy in 2017. The first USS Little Rock (CL-92) was turned into a museum.

In recent years, Little Rock has become more diverse. Besides two Spanish-language newspapers, El Latino and ¡Hoy! Arkansas, and a Spanish-language radio station, the city has a Buddhist center, an Islamic center, a Hindu center, two Korean churches, and two Orthodox churches. However, the city has also been a focal point regarding the issue of police violence, as exemplified by the 2010 killing of Eugene Ellison by a member of the Little Rock Police Department. In 2018, Frank Scott Jr. became the first African American elected mayor of Little Rock (Charles Bussey Jr. and Lottie Shackelford had previously served as mayor but were elected by the city’s board of directors).

Little Rock was one of many Arkansas locations affected by the Flood of 2019. On March 31, 2023, the city was hit by a tornado that damaged large portions of the city’s western and northwestern areas before proceeding across the river.

Education

Little Rock School District boundaries are not contiguous with city limits, especially to the west. The district has been completely out from under federal court supervision relating to the 1957 desegregation crisis since 2014. Little Rock is home to the Arkansas School for the Deaf and the Arkansas School for the Blind. Numerous private schools, both primary and secondary, are located within the city.

One of the earliest colleges in Little Rock, long defunct, was St. Johns’ College, which operated from 1859 to 1861 and then, after serving as a hospital during the Civil War era, was open again from 1867 to 1882. Institutions of higher learning in Little Rock include historically black Philander Smith University (founded in 1877), the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (1879), Arkansas Baptist College (1884), the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (1969), the University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law (1975), and the University of Arkansas Clinton School for Public Service (2005).

Industry

A number of nationally known companies are headquartered in Little Rock. Dillard’s, Inc., the nationally known department store chain that started in 1938 with William T. Dillard’s purchase of a small store in Nashville (Howard County), moved its corporate headquarters to Little Rock in 1964. The future Alltel, Inc., began in 1943 in Little Rock’s Hillcrest neighborhood shopping center, installing poles and equipment. In January 2009 Alltel merged with Verizon Wireless, based in New Jersey, which chose to make the Little Rock offices a regional headquarters. Acxiom, Inc., which was founded in 1969 in Conway (Faulkner County), had its headquarters to Little Rock from 1999 to 2017. WEHCO Media, Inc., based in Little Rock since its creation in 1909, is a privately-owned communications company which operates daily and weekly newspapers, magazines, and cable television companies in six states.

Heifer Project International was founded in 1944 by Dan West. The project long had an animal holding center in Perry County and, in 1971, moved its headquarters from St. Louis, Missouri, to Little Rock to be closer to the holding center. A new world headquarters for Heifer International was opened in downtown Little Rock in 2006 at 1 World Avenue, and a global village and education center opened in 2009.

Although located in Pulaski County north of Jacksonville, the Little Rock Air Force Base is generally associated with Little Rock. The site was chosen in 1952 after the citizens of Arkansas donated 6,000 acres. The base was activated on August 1, 1955, and, after serving many missions, including acting as a base for Titan II missile operations during the 1960s, is today America’s only C-130 training base.

The Group is an intentional community that relocated from Lamar (Johnson County) to Greers Ferry (Cleburne County) and finally to Little Rock. They have established a number of successful businesses, including the Internet service provider Aristotle, Inc.

Non-Profit and Religious Organizations

Camp Aldersgate has served the community in many ways since opening in 1947, including as a camp location for: peaceful integration talks during the Central High Crisis, children with physical and developmental disabilities, and evacuees from Louisiana after Hurricane Katrina.

Winrock International houses its headquarters in Little Rock. Its project foci are as far-reaching as agriculture, clean energy, and immigration. It opened in 1973 and is named for Governor Winthrop Rockefeller.

The nuns of the Carmelite Monastery of St. Teresa of Jesus have served the Little Rock area since 1950. Among the most noteworthy religious schools are the Episcopal Collegiate School, which provides education for grades pre-K through twelfth, Catholic High School for Boys, and Mount St. Mary Academy for girls. The Missionary Baptist Seminary trains pastors of that denomination.

Attractions

BANKS & BUSINESSES

The forty-story Simmons First National Bank Tower at Broadway and Capitol, erected in 1986, is the tallest building in Arkansas. The building was known as the TCBY Tower until 2004 and then as the Metropolitan National Bank Building before Simmons First National Bank acquired Metropolitan.

BODIES OF WATER

Fourche Creek runs through southern Little Rock. Two Rivers Park lies between the the Arkansas River and the Little Maumelle River on land that used to be the Pulaski County Penal Farm.

BRIDGES

The Rock Island Bridge was originally constructed as a railroad bridge in 1899; it was converted to serve as a pedestrian bridge in 2011 to complement the William J. Clinton Presidential Center and Park. The Pulaski County Pedestrian/Bicycle Bridge, popularly known as the Big Dam Bridge, opened in September 2006, crossing the Arkansas River atop the Murray Lock and Dam west of Little Rock; it is the second-longest bridge built for pedestrians in North America.

CEMETERIES

Mount Holly Cemetery, dating to 1843, is located on the west side of Broadway between 11th and 13th streets. Other notable historic cemeteries include Little Rock National Cemetery and Oakland-Fraternal Cemetery.

DISTRICTS

Central High School and the surrounding area have been designated the Central High School Neighborhood Historic District. Other Little Rock districts include: Capitol-Main Historic District; Downs Historic District; Hanger Hill Historic District; Paul Laurence Dunbar School Historic District; and the Quapaw Quarter, where the Governor’s Mansion is located. The River Market District is home to the Witt Stephens Jr. Central Arkansas Nature Center.

FOOD & DRINK

Little Rock is home to some of the oldest restaurants in the state, such as Lassis Inn, catfish restaurant founded in 1905, and Bruno’s Little Italy, which first opened in 1949. During the twenty-first century, several breweries opened in Little Rock, including Diamond Bear Brewery, which later moved across the river to North Little Rock, and Lost Forty Brewing, the state’s largest brewery. Little Rock is also home to Rock Town Distillery, currently the state’s largest distillery.

OPEN TO THE PUBLIC

The Historic Arkansas Museum at 200 East 3rd Street was completed in 1941. It houses a museum and many restored buildings from Arkansas’s territorial days. The William J. Clinton Presidential Center and Library, named for William Jefferson Clinton, the forty-second president of the United States, opened in November 2004 at 1200 President Clinton Avenue.

Other modern attractions include Gillam Park, Wildwood Park for the Arts, the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts, the Robinson Auditorium, the Esse Purse Museum, the L. C. and Daisy Bates Museum, and the Museum of Discovery. War Memorial Stadium regularly hosts sporting events. White Water Tavern is a renowned venue for musical performance, while Murry’s Dinner Playhouse has been providing theatrical entertainment since 1967, while Weekend Theater has been staging theatrical performances at its present location since 1993.

PROPERTIES LISTED ON THE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES

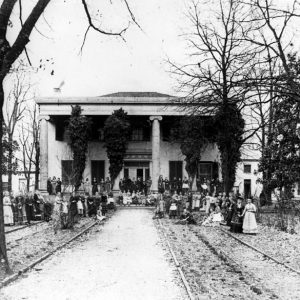

Significant for their architectural as well as historic value, many Little Rock properties are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, including: Trapnall Hall, Taborian Hall, and Curran Hall, which houses the Quapaw Quarter Association; Frederica Hotel, Lafayette Hotel, Marion Hotel, and Albert Pike Hotel and Albert Pike Memorial Temple (named for Albert Pike); the Cornish House, the Fowler House, the Hotze House, the First Hotze House, the Gustave B. Kleinschmidt House, the Marshall House, the Packet House, the Ten Mile House, the Thomas R. McGuire House, the William Woodruff House, and the White-Baucum House; St. Edward Catholic Church, the Cathedral of St. Andrew, Trinity Episcopal Cathedral; the Lincoln Building, the Democrat Printing and Lithographing Company Building; Lake Nixon, Boyle Park, Union Station, Trinity Hospital, Alexander House, Florence Crittenton Home, Shiloh Missionary Baptist Church, Gay Oil Company Building, Lincoln Avenue Viaduct, Lamar Porter Athletic Field, the Kahn-Jennings House, and Little Rock Fire Station No. 9, and the Tower Building.

In addition to being listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the Hornibrook House is now a bed and breakfast called The Empress, and the Villa Marre is a well-known landmark which was used in the opening credits of the television Show Designing Women. Presbyterian Village was built in 1965 as a new approach to progressive healthcare and living for senior citizens and remains popular today.

SCHOOLS

Little Rock Central High School, located at 1500 Park Street and the scene of the 1957 desegregation crisis, was built in 1927 as Little Rock Senior High School. Until 1940, this school was the largest high school building in the nation. In 1954, it was renamed Little Rock Central High School when Hall Senior High was built in the western part of the city.

The red-brick passenger terminal of the Choctaw Freight Terminal is now part of the Clinton School.

Notable Figures

ACTIVISM & CIVIL RIGHTS

Ed Whitfield, a civil rights activist most notable for the 1969 armed takeover of the student union at Cornell University, was born in Little Rock.

EDUCATION

Helen Booker Ivey was a longtime teacher and principal in Little Rock public schools. The Colored Branch of the Little Rock Public Library was renamed in her honor in 1951. The branch remained the primary library for Little Rock’s black community until the library system was fully integrated.

FILM

Actresses Fay Templeton and Gail Davis were born in Little Rock, as was child actress Ann Gillis. Filmmakers Brent Renaud and Craig Renaud were raised in Little Rock. Matt Besser is an Arkansan comedian, actor, writer, director, and teacher.

GOVERNMENT

City officials of note have included mayors Alexis Karl Hartman, Frederick Kramer, J. V. Satterfield, and Pratt Remmel; city manager John Meriwether; and city director Sharon Priest. Irma Hunter Brown became the first African-American women elected to the Arkansas House of Representatives and the first elected to the Arkansas Senate.

INDUSTRY

Additional figures of note include businessman Nathan Warren, entrepreneur Myra Jones, and Sharper Image founder Richard Thalheimer. Odell Smith of Little Rock was the state’s foremost trade union leader in the middle of the twentieth century.

LAW

Lawyers of note include Absalom Fowler, Frank Chowning, James McHaney, and Sidney Williams.

LITERATURE

Authors such as Dee Brown, Charles Portis, Grif Stockley, Melissa Scott, Kevin Brockmeier, and Ayana Gray have made their homes in Little Rock.

MEDIA

Morgan Beatty was one of the most eminent reporters and commentators during the early years of broadcast news. Little Rock was also home to journalist Herbert Denton Jr.

MEDICINE AND SCIENCE

Sophronia Reacie Williams was one of the first African-American nurses in hospitals and universities in Missouri, Ohio, and Colorado. Isaac Thomas “Ike” Gillam IV was first Black person to lead a NASA center as the Director of NASA’s Dryden Flight Research Center. John Jumper was a co-recipient of the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

MUSIC

Sister Ernestine Washington was a gospel singer associated with the Church of God in Christ (COGIC). Among the city’s more eclectic residents of note were Elton and Betty White, an interracial couple with a significant age difference whose musical performances shocked and delighted, featuring highly sexualized song lyrics. Little Rock has also been home to avant-garde cellist Charlotte Moorman, alternative rock band Evanescence, and singer and actor Dick Hogan, among many others.

RELIGION

Reverend Caleb Darnell Pettaway led the National Baptist Convention of America from 1957 to 1967.

SPORTS

Solly Drake and Sammy Drake were the first African American brothers to play major league baseball in the modern era. Derek Fisher is one of the most successful basketball players to hail from Arkansas.

For additional information:

Balko, Radley. “Big Trouble in Little Rock: A Reformist Black Police Chief Faces an Uprising of the Old Guard.” The Intercept, December 18, 2021. https://theintercept.com/2021/12/18/little-rock-black-police-chief-keith-humphrey/ (accessed June 29, 2023).

Bell, James W. Little Rock Handbook. Little Rock: James W. Bell, 1980.

Bell-Toliver, LaVerne, ed. The First Twenty-Five: An Oral History of the Desegregation of Little Rock’s Public Junior High Schools. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2018.

Campbell, Monica N. “‘Slums Are Our Most Expensive Luxuries’: Little Rock’s Metroplan and the Making of the Neoliberal City, 1939–1980.” PhD diss., University of Mississippi, 2021. Online at https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/2150/ (accessed June 29, 2023).

Chovanec, Zuzana, and Timothy S. Dodson. “The Early History of Streetcar Transportation in Little Rock, 1870–1948.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 54 (April 2023): 44–58.

City of Little Rock. http://www.littlerock.org/ (accessed June 29, 2023).

Craw, Michael. “Exit, Voice, and Neighborhood Change: Evaluating the Effect of Sub-Local Governance in Little Rock.” Urban Affairs Review 55 (March 2019): 501–529.

Cross, Isaac J. “Little Rock’s Unique Political Opportunities for Black Arkansans, 1865–1905.” MA thesis, Arkansas Tech University, 2023.

Feild, Charles R. Feild Notes on Little Rock: History and Memoir, 1622–2024. Little Rock: Nandina Books, 2025.

Hanley, Ray. Little Rock Then and Now. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2007.

Herndon, Dallas. T. Why Little Rock Was Born. Little Rock: Central Printing Company, 1933.

Jennings, Jay. Carry the Rock: Race, Football, and the Soul of an American City. New York: Rodale, 2010.

Kirk, John A. Beyond Little Rock: The Origins and Legacies of the Central High Crisis. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2007.

———. Redefining the Color Line: Black Activism in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1940–1970. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002.

Lester, Jim, and Judy Lester. Greater Little Rock. Norfork, VA: The Donning Company, 1986.

Mapping Little Rock History. Center for Arkansas History and Culture, University of Arkansas at Little Rock. https://mappinglittlerockhistory.ualr.edu/ (accessed November 6, 2024).

Mills, Letha, and H. K. Stewart. Little Rock: A Contemporary Portrait. Chatsworth, CA: Windson Publications, 1990.

Pierce, Michael. “Revenge of the Elite: The City Manager System and the Collapse of Racial Moderation in Little Rock, 1955–1957.” Arkansas Times, March 2018, pp. 67–75. Online at https://www.arktimes.com/arkansas/revenge-of-the-elite-in-little-rock/Content?oid=28592759 (accessed June 29, 2023).

Richards, Ira Don. Story of a Rivertown: Little Rock in the Nineteenth Century. Benton, AR: 1969.

Roy, F. Hampton, Charles Witsell Jr., and Cheryl Griffith Nichols. How We Lived: Little Rock as an American City. Little Rock: August House, 1984.

Terry, Bill. “Little Rock’s Most Crucial Election: The Thorny and Contrary Issue of How Does Your City Grow.” Arkansas Times, October 1976, pp. 8–15, 26–30.

Vinzant, Gene. “Mirage and Reality: Economic Conditions in Black Little Rock in the 1920s.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 63 (Autumn 2004): 261–278.

Williams, C. Fred. Historic Little Rock: An Illustrated History. San Antonio, TX: Historical Pub. Network, 2008.

Witsell, Charles, and Gordon Wittenberg. Architects of Little Rock: 1833–1950. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2014.

James W. Bell

Pulaski County Historical Society

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.