calsfoundation@cals.org

West Ninth Street (Little Rock)

aka: West 9th Street

West Ninth Street in Little Rock (Pulaski County) emerged as a predominately African American neighborhood during the Civil War. In 1863, the Federal army, which occupied Little Rock, began constructing log cabins in the area for freed slaves. After the war, many stayed and settled there. By 1870, what was originally known as Little Rock’s West Hazel Street was renamed West Ninth Street. More African Americans settled west of Mount Holly Cemetery between 9th and 12th streets. As the population grew, a five-block section along West Ninth Street, between Broadway and Chester, became the center of the Black business district.

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, African Americans created fraternal organizations, one of the most prominent of which was based on West Ninth Street. The Mosaic Templars of America (MTA) was established in 1882 by Chester W. Keatts and John Edward Bush, two former slaves who later became employees of the U.S. Postal Service’s Railway Mail Service. Bush also served as principal of the Capital Hill School, Little Rock’s first public school for African Americans. The MTA offered life and burial insurance policies. By 1883, the MTA had received its official state charter. From 1884 to 1895, the order operated the Mosaic National Building and Loan Association (MNBLA), which provided loans to MTA members who were considered “good credit risks.” In 1913, the MTA built its headquarters at the corner of 9th and Broadway, and this became a center for business and entertainment in the West Ninth Street district.

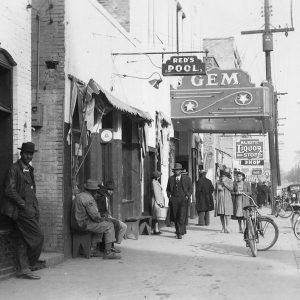

Jim Crow laws were statutes passed in most states in the South starting in the 1880s, creating artificial racial barriers between African Americans and whites. These laws prevented them from going to the same schools, riding in the same railcars, and sitting in the same sections at public venues. As a consequence of increased segregation, West Ninth Street became known as “the Line,” the name connoting the color line separating Black and white communities. The area surrounding the West Ninth Street was known by this time as the “colored section” of Little Rock and “a city within a city.”

Taborian Temple opened in 1918 at 800 West 9th on the opposite end of “the Line” from the Mosaic Templars building. Black business owners occupied five blocks between West Broadway and Chester streets in downtown Little Rock, with a laundromat, restaurants, stenographer and notary public offices, retail shops, and more. The 1920s was known as the “Golden Era” for the area’s Black community. West Ninth Street continued to grow throughout this time, but the Great Depression of the 1930s devastated many businesses and fraternal groups in downtown Little Rock, including the Mosaic Templars. Between 1930 and 1935, eleven percent of West Ninth Street’s businesses (sixteen total) closed. The Templars themselves declared bankruptcy soon after the crash, which resulted in the closing of the Mosaic State Hospital by 1940, as vacancies increased. By 1935, the Mosaic State Temple building had ten vacancies, with its entire second floor of offices completely vacant.

During the 1930s, social clubs began using Taborian Temple’s spacious third floor for dances and club meetings. Clubs like the Modernistic Club and, later, Club Morocco and Twin City Club established their spots in the building and sponsored dances there. On January 31, 1935, the Les Quatre Roses Club sponsored its first annual dance at Taborian’s Dreamland Ballroom. Approximately 250 guests enjoyed live music performed by the legendary jazz singer Billie Holiday. Dreamland Ballroom became known for hosting high-class and high-profile events, featuring big names in music such as Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, Nat King Cole, Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, B. B. King, and a host of others. By the 1940s, Philander Smith College and Dunbar High School also used the Dreamland Ballroom for social functions. In 1941, S. W. Tucker opened a new nightclub called The Club Aristocrat, changing the name of the former Dreamland Ballroom. Meanwhile, the Morocco sponsored artists such as Sam Cooke, Etta James, Count Basie, and Otis Redding.

A spirit of entrepreneurialism hit West Ninth Street with the American entry into World War II in 1941. Due to racial segregation, Black soldiers had only two options for entertainment venues close to Camp Robinson: Washington Avenue in North Little Rock (Pulaski County) and West Ninth Street in downtown Little Rock. The soldiers liked the downtown atmosphere, which created a business boom for West Ninth. The area also became a main hang-out spot for high school and college students. Attractions ranged from the Gem Theater to Dean Johnson’s Café and Drive-In. Liquor, music, pool halls, night clubs, and live entertainment events attracted soldiers and students, as well as the aristocrats of the Black community.

West Ninth boomed during the 1940s and 1950s, with dance clubs and live entertainment providing an outlet for the Black community. However, despite (or due to) the many flourishing businesses along West Ninth Street, this Little Rock community faced demolition and clearance as part of the national Urban Renewal project. Urban Renewal came by way of the Federal Housing Act of 1949, which aimed to modernize “blighted” areas within cities. The Little Rock Housing Authority (LRHA) told owners to sell at the appraised price or expect further action, including eviction by court order. B. Finley Vinson, former director of the LRHA and its slum clearance and urban redevelopment project at the time, later stated that “the city of Little Rock through its various agencies including the housing authority, systematically worked to continue segregation.” For those who refused to sell, the LRHA then began evicting residents and business owners from downtown, after which West Ninth Street’s businesses rapidly declined, with most closing by the mid-1960s.

Housing units were constructed on the far edge of Little Rock’s city limits for former residents who once occupied the West Ninth Street area. Between 1958 and 1961, plans were underway to turn West 8th and 9th streets into one-way streets. This would have been detrimental to the last few remaining businesses left on these streets, and local business owners took their case to court, but to no avail, and the streets became one-ways. With businesses and churches closed, and many residents gone, West Ninth Street was no longer “the mecca of entertainment in the South.” Also affecting businesses and homes in the area was the construction of Interstate 630 beginning in the 1960s, which has been blamed for significant social alterations in the state’s capital city, exacerbating racial and economic divides.

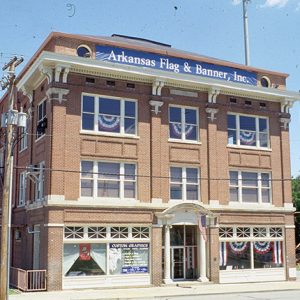

The only surviving structure from the heyday of the neighborhood is Taborian Hall, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982. In 1991, Arkansas Flag and Banner purchased the building, and business owner Kerry McCoy began working to renovate Dreamland Ballroom. In 2018, it was announced that the U.S. Department of the Interior and the National Park Service planned to award a $499,668 improvement grant for the ballroom’s restoration.

For additional information:

Bush, A. E., and P. L. Dorman. History of the Mosaic Templars of America: Its Founders and Officials. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2008.

Lost West Ninth Street. Roberts Library of Arkansas History and Art, Central Arkansas Library System. https://robertslibrary.org/lost-west-ninth-street/ (accessed November 4, 2021).

Love, Berna J. End of the Line: A History of Little Rock’s West Ninth Street. Little Rock: Center for Arkansas Studies, 2003.

Smith, Shanika. “The Success and Decline of Little Rock’s West Ninth Street.” Pulaski County Historical Review 67 (Summer 2019): 41–50.

Sorrows, Devin Matthew. “Life along the Color Line in Little Rock: An Archeological Investigation of Two Sites on South Arch Street.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2019.

———. “Memory Unearthed: An Archeological Investigation of Two Sites on Little Rock’s Historic West Ninth Street.” Pulaski County Historical Review 68 (Fall 2020): 66–70.

Vinzant, Gene. “Mirage and Reality: Economic Conditions in Black Little Rock in the 1920s.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 63 (Autumn 2004): 261–278.

Shanika J. Smith

Henderson State University

Mosaic Templars Headquarters

Mosaic Templars Headquarters  Mosaic Templars Headquarters

Mosaic Templars Headquarters  Taborian Hall

Taborian Hall  Taborian Hall Interior

Taborian Hall Interior  Taborian Hall, 1918

Taborian Hall, 1918  West Ninth Street

West Ninth Street  West Ninth Street

West Ninth Street  West Ninth Street

West Ninth Street  West Ninth Street

West Ninth Street

This is really sad! 😢 There were some nice little houses that could’ve been restored.