calsfoundation@cals.org

World War II

During World War II, Arkansas underwent fundamental social and economic changes that affected all parts of the state. From the creation of ordnance plants to the presence of prisoners of war (POWs) and Japanese-American internees, the impact of the war meant that the Arkansas of 1945 was vastly different from the Arkansas of 1941. In some ways, this reflected issues particular to Arkansas, while in other ways it reflected the profound changes that the United States as a whole underwent during the war. Along with the lingering effects of the Great Depression, the transformations that were brought about by World War II were to form a clear break between prewar and postwar Arkansas. Industrialization, urbanization, and migration all dramatically transformed the state.

The war had a great economic and social impact on the people of Arkansas. During the war, an estimated 194,645 Arkansans (about ten percent of the 1940 population of 1,949,387) served the nation in the various branches of the U.S. armed forces, and 3,519 were killed as a result of combat. Eleven men with Arkansas ties—four of them graduates of the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County)—earned the Medal of Honor in World War II. Arkansas National Guard troops saw service in combat theaters around the world, including units sent to Alaska in the months before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, where they fought small but brutal battles with Japanese troops in what has been called the Williwaw War (so named after strong winds associated with the weather of the region).

Families in Arkansas had to endure the worry and fear of sending family members off to war while at the same time struggling with the many changes taking place on the home front. For most, the immediate concern was dealing with the rationing of a vast array of consumer products. Most items were in short supply, and some items, such as new car tires, became all but unobtainable. To provide additional food, many Arkansans in towns and cities planted Victory Gardens in any available space to grow what they could to augment their rations. On February 8, 1943, Governor Homer Adkins proclaimed a “Victory Garden Day” to promote the practice across Arkansas. Even though the state ranked toward the bottom in terms of per capita income, this poverty did not stand in the way of citizens doing what they saw as their patriotic duty. During the war, Arkansas ranked twelfth overall in terms of war bond money raised among the forty-eight states of the Union.

As the U.S. military geared up to fight the Axis powers, a large number of wartime production plants were built across the country. Arkansas was home to six of these military ordnance plants. Built in the central and southern parts of the state, they were located in Camden (Ouachita County), El Dorado (Union County), Hope (Hempstead County), Jacksonville (Pulaski County), Marche (Pulaski County), and Pine Bluff (Jefferson County). The new plants became an important source of industrial jobs for Arkansas, which had suffered severe job loss during the Great Depression. At the peak of military production, more than 25,000 defense workers—mostly women—produced hundreds of millions of pounds of explosive material (such as ammonium picrate and nitrate) and millions of tons of other war materiel (such as detonators, fuses, and explosive primers). Housing and transportation for these “instant” cities became a pressing issue, as plants were constructed in record time in order to gear up the nation for war. Five of the facilities (Camden, El Dorado, Jacksonville, Marche, and Pine Bluff) were engaged in the actual production of war materiel, and the sixth, in Hope, was designated as a proving ground for the testing of ordnance being produced elsewhere.

However, the relatively low industrial wages paid in Arkansas led to a massive outflow of workers to other states. Between 1940 and 1943, more than ten percent of Arkansans left the state to work elsewhere. Many never returned to Arkansas, settling in areas such as Michigan and California. Meanwhile, nearly fifty percent of the state’s teachers, who normally earned around $700 a year, left the field of education during the war to earn the higher wages being paid in wartime industries—up to $2,400 a year. This led many schools to fail due to a lack of teachers, thus further hindering attempts to improve the educational achievement of Arkansans.

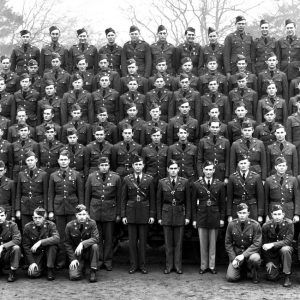

World War II opened up Arkansas to the rest of the country. Service personnel from other parts of the United States were exposed to Arkansas when they were stationed at camps around the state during the war. Camp Joseph T. Robinson in North Little Rock (Pulaski County) became a massive military installation with tens of thousands of soldiers living there at any one time. First built in 1917 for training during World War I, it was known as Camp Pike until it was renamed in 1937 for U.S. Senator Joseph Taylor Robinson. The U.S. entry in World War II saw a great expansion of the camp, which served as a site for both basic training and the training of medics for the U.S. Army. By 1946, about 750,000 troops had passed through the camp in the previous five years. Part of the camp was also used to house German POWs.

The large number of African-American troops who served in World War II brought about tensions in Arkansas as African-American soldiers from the North who trained and passed through the state at times refused to show deference to local whites. More and more Black troops chafed under the blatant hypocrisy of fighting for the idea of liberating nations overseas while facing racism both at home and in the military.

The demand for training facilities led to the construction or expansion of a number of facilities across the state. One of the larger facilities was Camp Chaffee (now Fort Chaffee), where construction was started in 1941 on a facility that eventually covered an area more than 100 square miles. A number of smaller facilities were built in rural areas around the state. Among these were U.S. Army airfields in towns such as Walnut Ridge (Lawrence County), Newport (Jackson County), and Stuttgart (Arkansas County). Arkansas also played host to a most unusual military base, Camp Magnolia, which was located near Magnolia (Columbia County). This was a camp that housed conscientious objectors (COs), those who refused to serve in the armed services. The men who were sent to the camp worked on conservation projects in the area. Relations between the men at the camp and local citizens were contentious, as COs were considered unpatriotic.

In addition to the hundreds of thousands of American troops who passed through the state, Arkansas also found itself hosting two very different groups of people during the war: Japanese-American internees from the West Coast of the United States and Axis prisoners of war. In the wake of the December 7, 1941, Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, many Americans were concerned about the loyalty of Japanese Americans living on the West Coast. Even though the majority of the internees were American citizens, 110,000 Japanese Americans were relocated against their will (and in violation of their civil rights) to remote locations far from the West Coast, for fear that they would carry out acts of sabotage against military installations or that they would spy for Japan. Arkansas was home to two of these internment sites: one at Rohwer (Desha County) and a second at Jerome, in an area that covered parts of Chicot and Drew counties. Between 1942 and 1945, almost 16,000 Japanese Americans were held in these two camps. The presence of so many Japanese Americans caused tensions with local Arkansans, who were not prepared for such an influx of a specific ethnic group. They also resented the living conditions of the camp, which were better than what some local residents experienced.

Even while suffering this gross violation of their civil rights, however, many men in the camps who were of military age chose to fight for the same government that was imprisoning their families. The camp at Rohwer produced 274 volunteers, and fifty-two joined from the Jerome camp. The men from both camps joined the U.S. Army’s 442nd RCT (Regimental Combat Team) that fought with great valor in Italy. One of the Rohwer enlistees, Ted Tanoye, was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for action at Molino A Ventoabbto, Italy.

Along with the internment of Japanese Americans, Arkansas saw the introduction of more than 23,000 German and Italian POWs to camps in the state. The U.S. government did not want to open POW camps in the United States, but Britain simply lacked the space and resources to take care of them. Due to concerns over security and the potential for panic and fear among the general populace, the POWs were often sent to mainly rural sites in the United States. In Arkansas, while the main camps were located at Camp Chaffee in Fort Smith (Sebastian County), Camp Dermott in Dermott (Chicot County), and Camp Robinson in North Little Rock, POWs were distributed among thirty branch work camps, mostly located in isolated sections of the Delta region. Camp Dermott was located at a site that was formerly used as the Jerome Relocation Center for Japanese Americans. Many of the Germans and Italians who were housed there were members of the Afrika Korps who had been captured in fighting in North Africa.

The end of the war brought an abrupt change to Arkansas. After the victories in Europe and the Pacific, the demand for war materiel vanished, and the jobs in the ordnance plants mostly disappeared. While many parts of the United States saw a prolonged postwar economic boom, Arkansas was in many ways bypassed in this regard. The lack of long-term investment in basic infrastructure, economic development, and educational opportunities was to be felt in postwar Arkansas as the population fell by almost 40,000 between 1940 and 1950. Many people who had left for better paying wartime jobs in other states simply stayed away. Especially dramatic was the decline in the African-American population, which fell from 482,578 in 1940 to 388,787 in 1960, a twenty-percent drop. Not until 1971 did the population of Arkansas rise above what it had been in 1940.

Throughout this period, Arkansas had undergone a dramatic change. In 1940, just over half the people in Arkansas lived on farms. By 1950, only forty-two percent of the population lived on farms as Arkansas became increasingly urban. Agriculture had also changed as farms became more mechanized. In 1940, there were 12,564 tractors in the state; by 1945, there were 26,537 tractors in use. Arkansas entered the post–World War II era facing many social and economic challenges, as one generation of Arkansans gave way to another.

For additional information:

Arnold, Norma Sims, “On the Home Front: Clark County in World War II.” Clark County Historical Journal (2023): 99–133.

Bolton, Charles S. “Turning Point: World War II and the Economic Development of Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 61 (Summer 2002): 123–151.

Goldstein, Donald M., and Katherine V. Dillon. The Williwaw War: The Arkansas National Guard in the Aleutians in World War II. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992.

Johnson, Ben F. Arkansas in Modern America since 1930. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2019.

National Archives State Summary of War Casualties from World War II for Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard Personnel from Arkansas. https://www.archives.gov/research/military/ww2/navy-casualties/arkansas.html (accessed April 18, 2022).

National Archives World War II Honor List of Dead and Missing Army and Army Air Forces Personnel from Arkansas. https://www.archives.gov/research/military/ww2/army-casualties/arkansas.html (accessed April 18, 2022).

Nieser, Tracy. “The History of Camp Pike, Arkansas.” Pulaski County Historical Review 41 (Fall 1993): 64–71.

Orr, Tabitha. “Clifford Minton’s War: The Struggle for Black Jobs in Wartime Little Rock, 1940–1946.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 76 (Spring 2017): 23–48.

Polston, Michael David. “‘Howling Celebration of Complete Victory’: Little Rock Celebrates End of World War II.” Pulaski County Historical Review 73 (Fall 2025): 56–61.

Pritchett, Merrill R., and William L. Shea. “The Afrika Korps in Arkansas, 1943–1946.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 37 (Spring 1978): 3–22.

Ratermann, Travis. “A Week of Tragedies: Two Camp Robinson Battalions Overcome Accidents to Help in the World War II Effort.” Pulaski County Historical Review 68 (Spring 2020): 2–11.

Smith, C. Calvin. War and Wartime Changes: The Transformation of Arkansas, 1940–1945. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1986.

Drew Philip Halevy

Bentonville, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.