calsfoundation@cals.org

Williwaw War

The “Williwaw War” has become the common term for the World War II conflict between American and Japanese troops in the Arctic Aleutian Islands. The term “williwaw” apparently dates to the nineteenth century, though its origin is uncertain; it describes sudden violent gusts of wind, often accompanied by rain, snow, and fog. The Aleutian theater in the war held particular interest for Arkansans: according to a story widely believed at the time (and which may actually be true), the loss of a coin toss in July of 1941 resulted in assignment of the 206th Coast Artillery Regiment of the recently federalized Arkansas National Guard to Aleutian duty. The winners (as they then thought), New Mexico’s 200th, were dispatched to the tropical Philippines, just in time for the Japanese invasions.

The 206th arrived in Alaska in August of 1941, along with another Arkansas Guard unit, the 153rd Infantry Regiment. The infantry went mostly to the mainland, but the 206th constructed its primary base at Dutch Harbor on Amaknak Island, one of the Fox Islands group in the middle of the 1,400-mile chain. There they settled into what was intended as a defensive posture to prevent the Japanese from establishing naval or air facilities for strikes against the U.S. mainland. The Japanese, having similar worries about the vulnerability of their homeland to attack from U.S. forces in the Aleutians, soon established bases on Attu and Kiska, two of the archipelago’s westernmost islands.

The worst enemy of both groups was weather. The islands were regions of incessant rain and never-ending winter. A typical year sees 200 days of rain; daily lows in the thirties are common even in summer. This weather often killed soldiers, who drowned in high seas, got lost in fogs and crashed or died of exposure, or were killed in high winds by flying debris. The isolation, combined with wartime stress, also sapped morale—men in the north took their own lives in appalling numbers.

But sometimes the weather lifted. When it did, war came to the Aleutians. The Japanese bombed Dutch Harbor in 1942, and they were expelled from Attu and Kiska in 1943. The fight for Attu was fierce, with high casualties on both sides (more than 2,300 Japanese soldiers died, with only twenty-eight prisoners taken; 549 Americans were killed, and more than 1,100 were wounded). Kiska was different; American forces bombed and assaulted the island in August, but the Japanese had evacuated the garrison two weeks earlier. If the Aleutian engagements were at best a minor front in the Pacific theater, it is clear that American forces by their presence deterred any notions Japanese war planners might have entertained for Arctic-based attacks upon the American homeland.

The war’s worst victims were the Aleuts, who were evacuated into miserable living conditions and returned after unconscionable delays to find their homes looted and destroyed by their ostensible protectors. A Japanese invasion via the Aleutians greatly stimulated American awareness of and attention to Alaska. The Alaska Highway would be the best-known wartime engineering feat, but the war years also saw the development of telephone connections between Alaska and the lower forty-eight states. Amaknak Island has an Aleutian World War II National Historical Park and Visitor Center, dedicated to honoring the wartime service of U.S. and Canadian soldiers, as well as memorializing the maltreatment of the Aleuts.

For additional information:

Charles A. Williams Jr. Collection. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas. Finding aid online at https://cdm15728.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/findingaids/id/3032/rec/1 (accessed February 23, 2024).

Goldstein, Donald M., and Katherine V. Dillon. The Williwaw War: The Arkansas National Guard in the Aleutians in World War II. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992.

Maxwell, William E. “A History of the 206th Coast Artillery (Anti-Aircraft) Regiment of the Arkansas National Guard in the Second World War.” MA thesis, University of Central Arkansas, 1992.

Robert B. Cochran

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Military

Military Russell, William Leon

Russell, William Leon World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967 Lucien Abraham

Lucien Abraham  Alaska Defense Corps Patch

Alaska Defense Corps Patch  Umnak Island Supplies

Umnak Island Supplies  Umnak Island Village

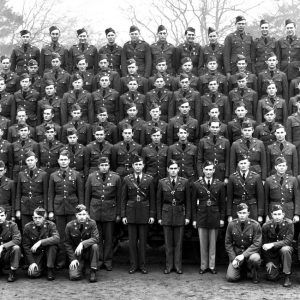

Umnak Island Village  Williwaw War Troops

Williwaw War Troops  Williwaw War Troops

Williwaw War Troops  Williwaw War

Williwaw War  Williwaw War

Williwaw War  Williwaw War

Williwaw War

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.