calsfoundation@cals.org

Hope (Hempstead County)

County Seat

| Location: | 33º40’04″N 093º35’27″W |

| Altitude: | 350 feet |

| Area: | 10.68 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 8,952 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | April 8, 1875 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

1,233 |

1,937 |

1,644 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

3,639 |

4,790 |

6,008 |

7,475 |

8,605 |

8,399 |

8,830 |

10,290 |

9,643 |

10,616 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10,095 |

8,952 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hope is on Prairie De Roan in southwest Arkansas. It is divided by Union Pacific Railway tracks traveling from northeast to southwest and is the birthplace of William Jefferson Clinton, the fortieth and forty-second governor of Arkansas and the forty-second president of the United States. Hope received national attention when Clinton closed his nomination acceptance speech at the 1992 Democratic National Convention with the words, “I still believe in a place called Hope.”

Reconstruction through the Early Twentieth Century

The town developed as the Cairo and Fulton Railway (predecessor to the Union Pacific) tracks were being laid from Argenta (now North Little Rock (Pulaski County)) to Fulton (Hempstead County). The first passenger train pulled into “Hope Station” on February 1, 1872. By the time the railway offered lots for sale, the wood-frame depot was almost complete. James Loughborough, the railroad company’s land commissioner, had named the workmen’s camp in honor of his daughter, Hope. The railway company drew the plat of the town and sold the first lots on August 28, 1873. The state had given the land to the company to defray building expenses. Walter Shiver built the first house near the depot in 1873. The town was incorporated on April 8, 1875, and the first officials were elected May 14. The Barlow Hotel opened in 1886, seeking to fill the need for lodging and dining (and continued as a successful business for eight decades). Three more railways arrived in Hope by 1902. Passenger service continued until 1971.

By 1900, the town had begun to produce its own electricity, an idea promoted by retired steamboat Captain Judson T. West, who had moved to Hope in 1875. An artesian well supplied water for the city. According to an 1888 article in the Arkansas State Gazetteer, Hope’s industries, businesses, and attractions included lumber mills, a wagon factory, a cotton compress, two banks, a hotel, several stores, a newspaper, a public school, and an opera house. In 1909, a Black man, possibly named Dillard, was lynched in Hope. Two years later, Charles Lewis, an African American man, was also lynched in Hope for allegedly making threats against the wife of a prominent planter. In 1921, another a black man, Browning Tuggle, was hanged from the water tower by a mob of hundreds for allegedly attacking a white woman.

Until construction of a highway bridge at Fulton in 1930, traffic crossed the Red River on a ferry. The routing of U.S. 67 (Broadway of America) through Hope in 1936 brought tourism.

The Arkansas Supreme Court declared Hope the county seat on May 11, 1939, after five bitterly fought elections to move the courthouse from Washington to Hope. An act of Congress in May 1824 had named Washington the county seat, but Hope citizens believed their town had become the commercial center of the county and its location more accessible. The Public Works Administration built Hope’s courthouse in 1939. Another New Deal structure is the Hope Girl Scout Little House.

World War II through the Modern Era

On July 1, 1941, the government announced a land condemnation order, and work began on the Southwestern Proving Ground (SPG). The government built the army ordnance plant on 50,000 acres of farmland just north of Hope. Four dozen army officers directed the activities and were assisted by an Army Air Corps detachment of about 150 men. Civilian employees—more than 750 daily—were transported by bus from Hope and surrounding counties. The plant was completed, and the first ammunition was tested January 1, 1942. Work continued until the end of the war in 1945. Some of the employees, both civilian and army, remained in Hope.

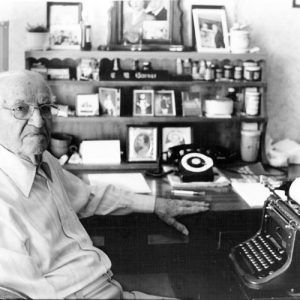

The Southwestern Proving Ground Airport was deeded to the city and dedicated as the Hope Municipal Airport on April 27, 1947, with an air show. In June, the government deeded 750 acres near the airport to be leased in support of the airport. During this same year, singer, activist, and writer Claud Wilton Garner published his first novel.

The War Assets Administration turned over to the city the deeds for 2,500 acres of the Southwestern Proving Ground land for an industrial area. When industry seeks to locate, the Federal Aviation Administration must approve the company’s lease or purchase of the land. The money is deposited in the Hope Municipal Airport Fund for its upkeep. Manufacturers in the industrial park include Temple Island, Borden Resins, Klipsch and Associates, and Tyson Foods. The American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars helped the city buy the officers quarters (now Oakhaven, an incorporated city) to assure veterans an opportunity to buy one of the houses. The federal government sold much of the original 50,000 acres of proving ground land to former owners.

Big Arkie, a thirteen-foot-long alligator, was caught in Hope in 1952. For eighteen years, he drew crowds to the Little Rock Zoo.

By the mid-1950s, Hope could not meet the demand for electricity and water. Its board of directors passed an ordinance requesting a Water and Light Commission, which was established in 1957 by legislative Act 115. Water is pumped from Millwood Dam through the Graves-Foster Water Treatment Plant at Fulton.

The Interstate 30 bridge over the Red River was completed in 1966. On November 10, 1972, the final section of I-30 officially opened, greatly improving travel from Little Rock (Pulaski County) to Dallas, Texas. The shift of businesses from downtown Hope to interstate exits had already begun. The Clinton Bypass, opened in sections since 1990, takes Arkansas 29S and U.S. 278E around the east side of Hope, providing an alternate traffic flow for heavy trucks.

Education

As was true across the South, Hope had a dual educational system until desegregation was accomplished in 1969, following government guidelines. Hope’s first public school for white children began in a small former Presbyterian church in 1880. The first teacher, Charles Bridewell, had had a private school the previous four years. The school board’s first building venture was a two-story red frame building in 1888. Its ad for a design was answered by fifteen-year-old Willis Jefferson Polk, an Illinois architect’s apprentice. The building was used for twenty years for the entire school, but, when increased enrollment demanded, a “dream school” was built in 1908 on today’s courthouse site. It was named Garland Grammar School and became Garland High School in 1922 but was condemned in 1930 because of poor construction. With the sale of its property to the county and revenue from consolidation of several rural schools, a modern three-story brick building was constructed at the south end of Main Street in 1931. It has been used as a high school since then.

The first school for black children was in a one-room building on South Hazel Street that opened October 1, 1886, with Henry Clay Yerger, an African American, the only teacher. A few years later, Yerger built Shover Street School. Later, Yerger was instrumental in securing funding for his educational projects from the General Education Board, the Rosenwald Foundation, and Smith-Hughes and Slater Funds; in 1918, he built a dormitory to accommodate girls who wanted to attend high school. A teacher-training summer school that Yerger established in 1895 continued until 1935. It was one of three summer schools for black teachers in Arkansas; the others were in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) and Little Rock. On October 18, 1935, Yerger was honored for his fifty years of teaching with a two-day event, during which the high school was named Henry Clay Yerger High School.

Hope public schools include William Jefferson Clinton Primary (kindergarten through fourth grades), Beryl Henry Elementary (fifth and sixth), Yerger Middle School (seventh and eighth), and Hope High School.

Red River Vocational Technical School, on sixty acres in south Hope, opened in 1966. On July 1, 1996, it became part of the University of Arkansas system and was renamed the University of Arkansas Community College at Hope. After the growth of a Texarkana (Miller County) campus, opened in 2012, the college was renamed University of Arkansas University of Arkansas Hope-Texarkana (UAHT) in 2019.

Industry

Hope’s economy has always depended on farming. Cotton was the chief crop until the 1920s. More than 30,000 bales a year were produced in the mid-1930s. So many buyers had offices on 2nd Street that it was known as Cotton Row. The United Cotton Seed Oil Mill was a successful industry as long as cotton was grown. More diversified farming began to be encouraged when the University of Arkansas Experiment Station was established near Hope in 1930.

The poultry industry in Hope began when Freda R. Greenan moved her business to Hope from Illinois in 1951, helping to revive the economy by encouraging farmers to raise chickens. Though she sold Corn Belt Hatcheries of Arkansas in 1964, the industry remains. A hospital and three banks also provide jobs.

Hempstead County’s rich hardwood forests provided good timber for lumber companies and manufacturers. The Ivory Handle Factory, incorporated in 1901, produced hardwood handles that were shipped worldwide, in addition to other wood products. It became Bruner Ivory Handle Factory in 1933, was sold to a Tennessee company in 1980, and closed in 2004.

The clay soil of the land south of Hope had been used to make pottery and bricks for many years when Norris P. O’Neal came to town on May 13, 1901, to establish Hope Brick Works. The last bricks were made there in November 2000, and the company was sold in January 2001.

On February 23, 2017, the Hempstead County Quorum Court voted to purchase the three-story Farmers Bank & Trust Building on 200 E. Third Street to serve as the new courthouse, the old one having been deemed unsafe due to mold and asbestos. Voters in 2020 approved a sales tax, to be in effect for two years, to fund renovations, and the grand opening for the new courthouse was celebrated on May 19, 2022.

Attractions

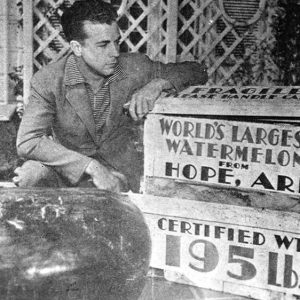

John S. Gibson, a druggist who also sold seeds, started a watermelon-growing competition to promote the economy in the 1920s. It has continued to draw interest, especially after the Ivan and Lloyd Bright 1979 and 1985 melons were listed in the Guinness Book of World Records. The Hope Chamber of Commerce sponsored the first Watermelon Festival in 1926; in August 2004, more than 20,000 attended the four-day event.

The 1912 Iron Mountain depot was rededicated in 1996 as a visitor center and museum. Exhibits include the history of Hope, the story of Hope’s world champion watermelons, Missouri Pacific Railroad memorabilia, and the life of Clinton from Hope to the White House.

The Coliseum is the center of activities, including the Third District Fair and Livestock Show, the Watermelon Festival, and other community events. On December 28, 2005, two small lakes adjoining the park were dedicated as the Mike and Janet Huckabee Lakes. They were built by the Game and Fish Commission, the Arkansas Department of Transportation, and the Rotary Club to be used at no charge.

The Cairo and Fulton depot, Hope’s oldest building, was restored to its original condition after serving as a freight depot for fifty-three years since 1912 and the general office of Stephens Grocer Company for thirty-four years. In 1999, the Harold Stephens family donated the building to the city. It was dedicated March 12, 2004, and is now the Chamber of Commerce headquarters and the Paul W. Klipsch Conference Room and Memorial Garden.

Famous Residents

President Clinton was born William Jefferson Blythe III in Hope. When he was seven, his widowed mother married Roger Clinton, and the family moved to Hot Springs (Garland County). Later he took his stepfather’s name. His renovated first home is maintained by the William Jefferson Clinton Birthplace Foundation and visited by tourists from all over the world. Also from Hope joining Clinton in the White House were: Thomas F. “Mack” McLarty, his first chief of staff; and Vincent Foster Jr., deputy White House counsel.

Mike Huckabee, Arkansas’s forty-fourth governor, was born and raised in Hope and had a career as a Southern Baptist minister before entering politics. His wife, Janet McCain Huckabee, is also from Hope, as is their daughter, Sarah Huckabee Sanders, who served as the press secretary for President Donald Trump. George Frazier was a well-known business, civic, and political leader in Hope for six and a half decades. Mack McLarty’s father, Thomas Franklin (Frank) McLarty II, was a national leader in the truck-leasing business.

One of the Southwestern Proving Ground army ordnance officers, Major Paul W. Klipsch, an Indiana native, chose to stay in Hope after World War II. In 1948, he and one employee began the production of his now internationally famous Klipsch horns, speakers used in theaters and home stereo systems.

Artist Effie Anderson Smith was born near Nashville (Howard County) but spent most of her childhood and early adulthood in Hope before moving to the southwestern United States. Additional residents of Hope have included: politician Kelly Bryant, politician David Armstrong, Judges Ed McFaddin and Doris Pryor, newspaperman Alex Washburn, Lieutenant General Harry Jacob Lemley Jr., and performer Ketty Lester. Hidden Figures, a book and major motion picture from 2016, told the story of Dorothy McFadden Hoover and her peers, the first black women pioneering the field of aeronautical mathematics and research.

For additional information:

Bowden, Bill. “Little-Pond Hope Spawned Big Names.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, April 21, 2019, pp. 1A, 8A.

Roueché, Berton. Special Places: In Search of Small Town America. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1982.

Shiver, Harry W., ed. Hope’s First Century: A Commemorative History of Hope, Arkansas. Hope, AR: Hope Centennial Committee, 1974.

Southwest Arkansas Regional Archives. Washington, Arkansas.

Williams, Joshua. Hope. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2010.

Mary Nell Turner

Hope, Arkansas

Barlow Hotel

Barlow Hotel  Clinton Birthplace

Clinton Birthplace  Bill Clinton Presidential Campaign

Bill Clinton Presidential Campaign  Bill Clinton

Bill Clinton  Orval Faubus with Hope Melon

Orval Faubus with Hope Melon  FEMA Trailers

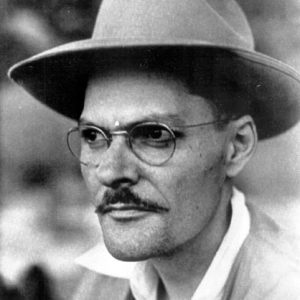

FEMA Trailers  Claud Garner

Claud Garner  Giant Watermelon

Giant Watermelon  Gibson Residence

Gibson Residence  Hempstead County Courthouse

Hempstead County Courthouse  Hempstead County Map

Hempstead County Map  Hope Savings Bank & Trust

Hope Savings Bank & Trust  Hope Street Scene

Hope Street Scene  Hope Street Scene

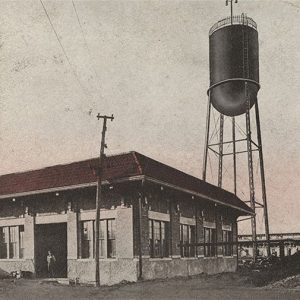

Hope Street Scene  Hope Utilities

Hope Utilities  Hope Watermelon Festival

Hope Watermelon Festival  Klipsch Memorial

Klipsch Memorial  Klipsch Headquarters

Klipsch Headquarters  Klipsch Museum Visitor Center

Klipsch Museum Visitor Center  Paul Klipsch

Paul Klipsch  Missouri Pacific Depot

Missouri Pacific Depot  Saenger Theater

Saenger Theater

(2007) Many cemeteries were moved during the creation of the Southwestern Proving Ground (SPG) in Hempstead County to make it a testing area for bombs, large shells, etc. We moved from McCaskill in 1942 and lived in Nashville in Howard County in a new stucco house that was built in 1941-1942, which suffered considerably from the bombings and shellings. By the end of World War II, you could see the pattern of the “chickenwire” understructure of the stucco, which resulted from the constant vibrating of the earth. The house is still standing at 1118 E. Peachtree (Prescott Highway).