calsfoundation@cals.org

Tourism

The term “tourism,” meaning “traveling as a recreation,” was not common in the nineteenth century, nor was the activity it denoted. By the year 2014, however, an estimated 26 million visitors to Arkansas spent approximately $6.7 billion annually in the state. Tourists come to Arkansas for its many sports and recreational opportunities, as well as its natural beauty.

Arkansas tourism may have taken root even in the eighteenth century. The decorated buffalo robes the Quapaw made that ended up in the Musée de l’Homme in Paris, France, were, in Judge Morris S. Arnold’s judgment, tourist souvenirs. Arkansas—which, because of John Law’s Mississippi Bubble scheme, had international recognition—attracted daring tourists. While Thomas Nuttall and George William Featherstonhaugh came on business, Washington Irving passed through on his way back from his Western tour. Tourist Albert Pike chose to stay, and Friedrich Gerstäcker wrote a book of hunting stories and returned after the Civil War.

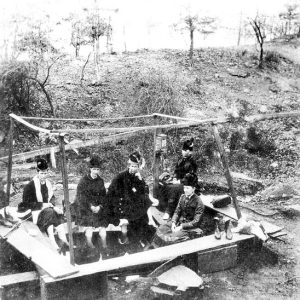

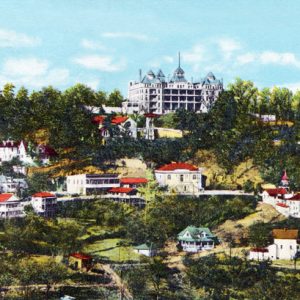

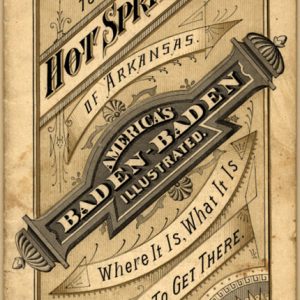

In the early nineteenth century, Hot Springs (Garland County) was one of several spa towns offering medicinal tourism. Competing towns after the Civil War included Ravenden Springs (Randolph County) and Eureka Springs (Carroll County). Arkansas tourism (and promotion) was formally launched in 1876 with the publication of A History of the North-western Editorial Excursion to Arkansas: A Short Sketch of its Inception and the Routes Traveled over, the Manner in which the Editors were Received, the Resolutions Adopted and Speeches Made at Various Points, the View of the Editorial Visitors to Arkansas as Expressed in their Papers (more commonly referred to as New Arkansas Travelers). Successful tourism depended on getting access to the chosen site. From the 1870s to about 1920, most tourists arrived by train. Eureka Springs’ growth was almost entirely due to the construction of a short line that connected to the Frisco Railroad’s main line at Seligman, Missouri. The transformation of this line into the Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad (the best known of this troubled line’s many names) then spurred tourism in Gilbert (Searcy County), Heber Springs (Cleburne County), and other stops. William Hope “Coin” Harvey’s resort at Monte Ne (Benton County) was nationally famous, and it, too, had its own rail line. Tourists who were headed for Ravenden Springs got off the Frisco at Ravenden (Lawrence County). Most resorts typically collected the tourists in wagons or hacks and transported them to the hotel or camp. Samuel Alexander Leath at Eureka Springs used a tallyho pulled by six white horses.

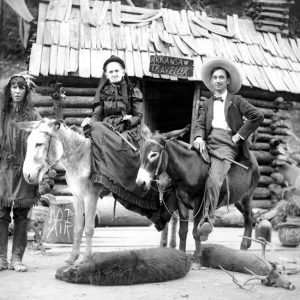

A new era of tourism began with the arrival of the automobile. In 1913, Coin Harvey helped launch the Ozark Trails Association that eventually marked more than 6,000 miles of roads, thus making the northwestern part of the state accessible to tourists. In consequence, a new industry arose—tourist courts. Erected often on the outskirts of town, the courts featured individual bungalows, often in the creek stone and cement style popular at the time. Sometimes the site itself had facilities. Particularly notable are the cabins at the cave at Cave City (Sharp County). Sometimes the owners added a restaurant as well. As pavement spread, more vehicles came bearing people seeking recreation. Bella Vista, an early Ozark retreat built around an artificial lake and a nightclub in Wonderland Cave, gave Benton County a taste of the high life. When interest in water for medicinal purposes declined, Eureka Springs lured tourists by celebrating the traditional culture of the Ozarks, thus inaugurating the Ozark Revival. Otto Earnest Rayburn was ambiguously cast both as the region’s principal promoter and one who wished to conserve the region’s traditional values. Rayburn and folklorist Vance Randolph both wrote books extolling the culture of a pre-modern age. The Ozark Revival had ramifications in the Ouachitas. The radio shows and motion pictures of two Mena (Polk County) businessmen, Chester Lauck and Norris Goff, better known as Lum ‘n’ Abner, celebrated homespun ways in a mythical town called Pine Ridge. Hoping to capitalize on their fame, the town of Waters in Montgomery County changed its name in 1936 to Pine Ridge. Another tourist site was the boyhood home of film star Bob Burns in Van Buren (Crawford County).

Celebrating traditional ways did not sit well with a portion of the state’s elite. They insisted Arkansas was and always had been thoroughly modern. Avantus “Bud” Green’s detailing of these issues in The Arkansas Challenge: A Bragging, Boasting, Swaggering, Toasting Handbook on the Wonder State (1946) remains the standard treatment.

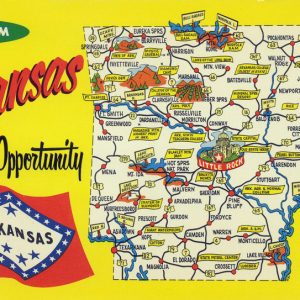

How to lure tourists into Arkansas and how to get them to spend money became a state issue in the 1920s. The Ozark Playground Association, organized in 1919, pushed the supposed pristine purity of both nature and inhabitants under the slogan, “The Land of a Million Smiles.” Former governor Charles H. Brough pushed persistently and successfully for the adoption in 1923 of “The Wonder State” as Arkansas’s official nickname. The more economically driven “Land of Opportunity” followed after World War II, but “The Natural State” took the state back to a tourist orientation. One state agency, State Parks and Tourism, created in 1925, was devoted to pursuing these elusive dollars, each one of which was calculated to have a “multiplier” effect on the local economy. Arkansas benefited from the New Deal Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) work in the Ozarks and Ouachitas. Roads and bridges helped open the region to tourists. In 1937, when the state legislature created the Arkansas Publicity Advisory Commission in order to promote more tourism, it expected not transient visitors but permanent settlers who would bring wealth and prestige to the state.

Another aspect of the tourist campaign was to keep Arkansans within the state to spend their tourist dollars. “See Arkansas First” was the slogan, and judging anecdotally, few Arkansans have seen much of their home state. It is the hope of many that programs on educational television and the teaching of Arkansas history in schools may lead to increased interest.

In general, scenic and recreational parks came first (Mount Magazine, Petit Jean), followed later by historical and cultural ones after 1970. One early cultural example is the Ozark Folk Center at Mountain View (Stone County). The state government of Arkansas entered the picture after Mountain View received federal funds to house its folk festival, which had started in 1963. In 1973, the state took over, acquiring the land and erecting buildings for the Ozark Folk Center, which is now designated as a state park.

By the early part of the twenty-first century, Arkansas had fifty-two state parks and many museums invariably directed at the different aspects of tourism. Parks and lodges near the state’s lakes cater to water sports or fishing. Historic Washington State Park displays much of the southwestern part of the state’s antebellum history. The first preservation project, originally called the Arkansas Territorial Restoration (now the Historic Arkansas Museum), was modeled on Colonial Williamsburg and claimed erroneously to have saved the first Little Rock (Pulaski County) home of the Arkansas Gazette. In time, the museum collected a broad range of Arkansas paintings, prints, and cultural artifacts. Near Scott (Pulaski and Lonoke counties), the state bought the misnamed Toltec Mounds and turned that Plum Bayou site into one of two parks related to Arkansas’s prehistory; the other is at Parkin (Cross County), a small Delta community located on the site of Casqui, a town Hernando de Soto is believed to have visited. At Scott is the state’s agricultural museum, the Scott Plantation Settlement. What had been the Oil and Brine Museum at Smackover (Union County) became the Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources. Finally, Arkansas commemorates its Civil War battles with a major park at Prairie Grove and smaller ones elsewhere.

The federal government’s contributions consist of the Arkansas Post National Memorial, although its remote site precludes much tourist traffic. The major Civil War battlefield site, Pea Ridge (Elkhorn Tavern) National Military Park, owes its origins to the work of local leaders. In 1998, the Little Rock Central High School National Historical Site opened to commemorate the 1957 desegregation of Little Rock Central High School. Downtown Hot Springs is a national park, and because the site had been owned by the federal government from the time of the Louisiana Purchase, it is America’s oldest national park. Arkansas achieved another first when the Buffalo River was accorded national status by President Richard Nixon. The Fort Smith National Historic Site features Judge Isaac Parker’s notorious court as well as other surviving buildings at the fort site.

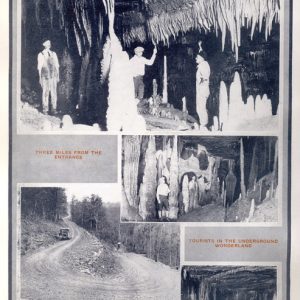

The state has many notable caves that attract visitors. Blanchard Springs Caverns is a magnificent limestone cave system starting more than 200 feet underground in the Sylamore Ranger District of the Ozark–St. Francis National Forest, fifteen miles northwest of Mountain View; the only cave administered by the U.S. Forest Service, it is considered one of the most beautiful in the country. Diamond Cave on Henson Creek, three miles from Jasper (Newton County), operated as a tourist attraction until the mid-1990s, when it was closed for its protection.

Theme parks were another late-twentieth-century addition. Magic Springs at Hot Springs and Gerald K. Smith’s Sacred Projects at Eureka Springs are the most popular. “Coin” Harvey’s Monte Ne ended up under the waters of Beaver Lake, and an Ozark hillbilly park called Dogpatch USA, located between Harrison (Boone County) and Jasper, opened in 1968 but closed a few years later.

Along with the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts, a large tourism draw in central Arkansas is the William Jefferson Clinton Presidential Library in Little Rock. Built along the Arkansas River just south of Interstate 30 in an award-winning style (which some saw as reminiscent of the ubiquitous double-wide manufactured home), it opened on November 18, 2004, and drew almost 500,000 visitors the first year. Other Little Rock attractions doubtless benefited from the ripple effect, but the greatest impact could be found in the adjacent River Market area, which spreads along Markham Street and includes the Main Library for the Central Arkansas Library System. Trolleys, last seen in 1948, returned to the downtown area as part of the Rock Region Metropolitan Transit Authority and linked to North Little Rock (Pulaski County) as well. The Clinton Presidential Library proved to be a draw for tour buses, many of which crisscross the state heading for such popular destinations as Branson, Missouri, for its shows or Tunica, Mississippi, for its casinos, or Eureka Springs for its Passion Play.

Hunting has also played a major role in Arkansas tourism. It was hunters and fishermen who demanded game laws to stop the promiscuous destruction being carried out by residents in the early twentieth century. Hunters are most drawn to eastern Arkansas. Stuttgart (Arkansas County) is famous for its duck hunts. Beer baron August Busch of St. Louis, Missouri, was a frequent visitor.

Nature-oriented tourism included two prominent hiking trails, one through the Ouachitas and the other through the Ozarks. When adequate water levels permit, the Buffalo National River is filled with canoes. The Mulberry, Spring, and Cossatot rivers are also popular.

One issue in the twentieth century was the legalization of gambling. Arkansas had only two legal forms of gambling, dog races at Southland Park Gaming and Racing in West Memphis (Crittenden County) and horse races at Oaklawn in Hot Springs. As casinos arose in Missouri and Mississippi, Arkansans hastened to take their dollars out of state. However, a law passed in 2005 allowed voters in West Memphis and Hot Springs to decide upon the inclusion of electronic “games of skill” on the grounds of racing facilities; the subsequent elections pitted moneyed pro-gambling interests against conservative churches, with the former winning the day. In 2008 Arkansas voters approved a state lottery, which supporters promised would help to fund scholarships to state colleges and universities.

In the twenty-first century, northwestern Arkansas became a major tourist draw, with the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art as a catalyst.

Finally, almost every community supports a fair or celebration of some sort. From Toad Suck Daze in Conway (Faulkner County)—where toads race—to the Turkey Trot Festival in Yellville (Marion County)—where live turkeys were once thrown out of airplanes—Arkansas is awash with events. One once-prominent event was the Picklefest at Atkins (Pope County) that featured pickle juice drinking contests. Sponsors were left in a bind when the company closed and moved to Mexico. Another festival that had difficulties was the King Biscuit Blues Festival in Helena-West Helena (Phillips County), which was faced with conflicts between organizers and lost the right for a time to use the historic King Biscuit name long associated with the event; in 2010, however, the management of the festival succeeded in regaining the use of the name.

Although tourism is dependent upon national economic conditions, state environmental problems have also impacted its potential, with some lakes and rivers losing their allure on account of pollution, even as the possible rediscovery of the ivory-billed woodpecker demonstrated yet again the draw of natural areas. But though Arkansas now bears the moniker of “The Natural State,” numerous sites, festivals, and other attractions help define the image of the state.

Impact of Travel on Arkansas Counties, 2013 – U.S. Travel Association

County Travel Economic Impact Model (CTEIM) – Alphabetical by County

| COUNTY |

TOTAL TRAVEL-GENERATED EXPENDITURES (DOLLARS) |

TRAVEL-GENERATED JOBS |

VISITORS |

| ARKANSAS | 36,162,133 | 314 | 152,820 |

| ASHLEY | 29,120,238 | 320 | 124,567 |

| BAXTER | 214,013,221 | 2,174 | 913,316 |

| BENTON | 298,946,481 | 3,300 | 1,319,531 |

| BOONE | 62,390,547 | 734 | 269,280 |

| BRADLEY | 11,451,190 | 82 | 41,897 |

| CALHOUN | 3,577,100 | 11 | 9,115 |

| CARROLL | 213,354,273 | 2,951 | 909,737 |

| CHICOT | 13,212,421 | 142 | 54,869 |

| CLARK | 54,482,564 | 568 | 234,177 |

| CLAY | 16,061,581 | 133 | 65,121 |

| CLEBURNE | 154,539,714 | 1,415 | 630,961 |

| CLEVELAND | 4,422,064 | 31 | 12,882 |

| COLUMBIA | 28,086,787 | 298 | 115,604 |

| CONWAY | 27,712,447 | 269 | 122,181 |

| CRAIGHEAD | 99,280,818 | 1,125 | 422,650 |

| CRAWFORD | 43,342,538 | 414 | 183,173 |

| CRITTENDEN | 170,820,141 | 1,867 | 728,677 |

| CROSS | 14,654,902 | 140 | 63,207 |

| DALLAS | 13,844,028 | 106 | 57,899 |

| DESHA | 23,170,554 | 271 | 101,706 |

| DREW | 26,486,811 | 308 | 111,877 |

| FAULKNER | 98,092,186 | 1,043 | 415,416 |

| FRANKLIN | 16,815,827 | 157 | 69,613 |

| FULTON | 24,370,041 | 238 | 98,909 |

| GARLAND | 642,831,151 | 6,959 | 2,607,708 |

| GRANT | 6,548,148 | 52 | 26,961 |

| GREENE | 25,878,859 | 276 | 111,604 |

| HEMPSTEAD | 49,311,126 | 526 | 201,432 |

| HOT SPRING | 34,322,356 | 294 | 138,029 |

| HOWARD | 4,258,316 | 23 | 18,631 |

| INDEPENDENCE | 37,153,973 | 450 | 157,911 |

| IZARD | 25,726,864 | 208 | 97,847 |

| JACKSON | 15,369,712 | 139 | 64,767 |

| JEFFERSON | 124,628,522 | 1,321 | 489,831 |

| JOHNSON | 30,835,283 | 322 | 134,570 |

| LAFAYETTE | 33,572,456 | 221 | 127,089 |

| LAWRENCE | 15,418,894 | 130 | 64,802 |

| LEE | 4,045,147 | 35 | 12,813 |

| LINCOLN | 4,898,204 | 32 | 19,589 |

| LITTLE RIVER | 23,833,465 | 192 | 94,399 |

| LOGAN | 12,253,857 | 114 | 46,386 |

| LONOKE | 34,869,356 | 308 | 139,774 |

| MADISON | 9,774,575 | 68 | 38,900 |

| MARION | 48,467,550 | 540 | 199,958 |

| MILLER | 82,617,868 | 723 | 339,323 |

| MISSISSIPPI | 100,927,377 | 1,207 | 445,861 |

| MONROE | 32,888,685 | 325 | 134,063 |

| MONTGOMERY | 30,909,830 | 264 | 113,029 |

| NEVADA | 24,615,645 | 163 | 67,386 |

| NEWTON | 12,556,377 | 143 | 50,680 |

| OUACHITA | 30,751,067 | 307 | 139,225 |

| PERRY | 19,341,166 | 127 | 70,156 |

| PHILLIPS | 27,971,810 | 274 | 114,477 |

| PIKE | 16,510,379 | 184 | 68,123 |

| POINSETT | 14,739,664 | 88 | 66,546 |

| POLK | 23,559,798 | 249 | 94,057 |

| POPE | 148,057,034 | 1,280 | 603,310 |

| PRAIRIE | 4,973,976 | 46 | 20,826 |

| PULASKI | 1,569,119,553 | 12,644 | 5,421,629 |

| RANDOLPH | 17,364,552 | 128 | 77,175 |

| SALINE | 56,599,963 | 626 | 236,612 |

| SCOTT | 6,761,628 | 66 | 24,914 |

| SEARCY | 10,053,178 | 84 | 50,146 |

| SEBASTIAN | 368,276,807 | 2,817 | 1,250,275 |

| SEVIER | 15,833,943 | 142 | 61,466 |

| SHARP | 46,232,543 | 374 | 180,464 |

| ST. FRANCIS | 44,017,548 | 409 | 185,975 |

| STONE | 74,116,440 | 785 | 308,967 |

| UNION | 115,751,109 | 888 | 432,613 |

| VAN BUREN | 58,368,197 | 540 | 222,083 |

| WASHINGTON | 354,796,630 | 4,208 | 1,503,126 |

| WHITE | 55,930,328 | 574 | 230,455 |

| WOODRUFF | 6,759,289 | 50 | 23,486 |

| YELL | 14,499,283 | 105 | 51,603 |

| TOTALS | 6,267,310,088 | 60,440 | 24,610,236 |

*Visitation data derived by Research and Information Services Section of Arkansas Department of Parks and Tourism.

Note: Details may not add due to rounding.

For additional information:

Arkansas Game and Fish Commission. Arkansas Wildlife. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1998.

Arkansas Tourism Official Site. http://www.arkansas.com/ (accessed August 10, 2023).

Gettinger, Aaron. “Smaller Counties Finding Tourism Niche.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, October 30, 2023, pp. 1A, 3A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/oct/30/smaller-counties-finding-tourism-niche/ (accessed October 30, 2023).

Hawkins, Ruth A. “Heritage Tourism in the Delta.” In Defining the Delta: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on the Lower Mississippi River Delta, edited by Janelle Collins. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2015.

A History of the North-western Editorial Excursion to Arkansas: A Short Sketch of its Inception and the Routes Traveled over, the Manner in which the Editors were Received, the Resolutions Adopted and Speeches Made at Various Points, the View of the Editorial Visitors to Arkansas as Expressed in their Papers. Little Rock: T. B. Mills & Co., 1876.

Keefe, James F., and Lynn Morrow, eds. The White River Chronicles of S. C. Turnbo: Man and the Wildlife on the Ozarks Frontier. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

Kesterson, Kayla Diane. “The Relationships between ‘Push’ and ‘Pull’ Factors of Millennial Generation Tourists to Heritage Tourism Destinations: Antebellum and Civil War Sites in the State of Arkansas.” MS thesis, University of Arkansas, 2013. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/983/ (accessed August 10, 2023).

King, Stephen A., and Roger Davis Gatchet. “Heritage Tourism, Origin Stories, and Arkansas Blues: Promoting Blues Tourism on Both Sides of the Mississippi River.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 53 (December 2022): 163–182.

Lankford, George. “Tourism in Lawrence County in 1819.” Independence County Chronicle 60 (January 2019): 3–8.

Myers-Phinney. “Arcadia in the Ozarks: The Beginnings of Tourism in Missouri’s White River Country.”OzarksWatch 3 (Spring 1990): 6–11.

Rose, F. P. “The Story of Sam A. Leath.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 14: 120–127.

Shipley, Ellen C. “The Pleasures of Prosperity, Bella Vista, Arkansas, 1917–1929.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 37 (Summer 1978): 99–129.

Simpson, Ethel C. “Otto Earnest Rayburn, An Early Promoter of the Ozarks.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 58 (Summer 1999): 160–179.

Spencer, Jim, “The Good Old Days,” Arkansas Times, December 1987, 44–47, 54.

Steward, Dana F. A Rough Sort of Beauty; Reflections on the Natural Heritage of Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2002.

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Welcome Centers

Welcome Centers Bella Vista

Bella Vista  Blanchard Springs Caverns

Blanchard Springs Caverns  Clinton Presidential Library and Museum

Clinton Presidential Library and Museum  Corn Hole Spring

Corn Hole Spring  Crescent Hotel

Crescent Hotel  Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art  Diamond Cave Brochure

Diamond Cave Brochure  Dogpatch USA Ad

Dogpatch USA Ad  Happy Hollow

Happy Hollow  Hope Watermelon Festival

Hope Watermelon Festival  Hot Springs Promotional Brochure

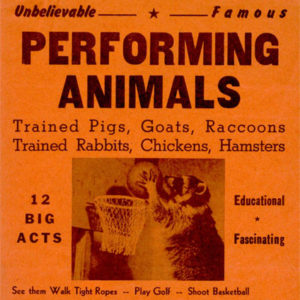

Hot Springs Promotional Brochure  IQ Zoo Handbill

IQ Zoo Handbill  "Land of Opportunity" Postcard

"Land of Opportunity" Postcard  Little Rock Central High Museum

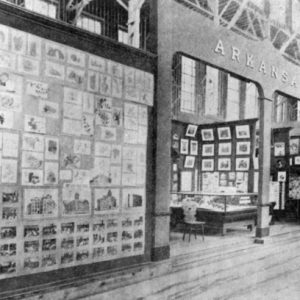

Little Rock Central High Museum  Louisiana Purchase Exposition Exhibit

Louisiana Purchase Exposition Exhibit  Murray Lock and Dam

Murray Lock and Dam  Ozark Folk Center

Ozark Folk Center  Parnell Springs Hotel

Parnell Springs Hotel  Syllamo Mountain Bike Trail

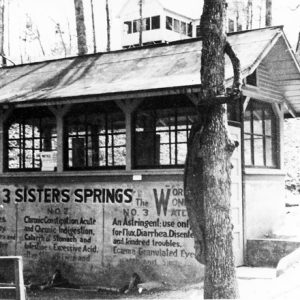

Syllamo Mountain Bike Trail  Three Sisters Spring

Three Sisters Spring  Tourist Couple

Tourist Couple  Welcome to Arkansas Sign

Welcome to Arkansas Sign

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.