calsfoundation@cals.org

Hot Springs (Garland County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 34º30’13″N 093º03’18″W |

| Elevation: | 632 feet |

| Area: | 37.47 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 37,930 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | January 10, 1851 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

201 |

1,276 |

3,554 |

8,086 |

9,973 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

14,434 |

11,695 |

20,238 |

21,370 |

29,307 |

28,337 |

35,631 |

35,781 |

32,462 |

35,750 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

35,193 |

37,930 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hot Springs is situated along the Ouachita River in the Central Ouachita Mountains division of the Ouachita Mountains. It is the largest city in the Ouachita Mountains and has been a resort center since its establishment in the early nineteenth century, but it is also known as a historic locus of illegal gambling, mafia activity, and political corruption. President Bill Clinton, born in Hope (Hempstead County), grew up in Hot Springs, and the city has attracted and produced many noteworthy politicians, artists, and writers throughout the years, including Mary Lewis and Marjorie Florence Lawrence. The daily newspaper the Sentinel-Record, in one incarnation or another, has been circulating in Hot Springs since its inception in 1874.

Pre-European Exploration through European Exploration and Settlement

The area around Hot Springs was occupied by Native Americans until about AD 1600; the most recent native inhabitants of the area were likely related to the historic Caddo Indians. Local legend speaks of the thermal springs as constituting a neutral ground in which various tribes, even those at war with each other, could co-exist in peace, at least temporarily, but these legends are no doubt later embellishments devised as part of an emerging tourist economy. However, there is evidence for early mining of area novaculite, which was used for various tools and spear points. Spanish explorers of the expedition of Hernando de Soto may have passed through what is now Garland County, but there is no evidence that de Soto himself visited the hot springs.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

The Hunter-Dunbar Expedition up the Ouachita River in 1804 included a four-week study of the hot springs, though the explorers were unable to discover the springs’ water source. The first permanent white settler was likely John Perciful in 1809. The site soon attracted regular visitors throughout the spring and summer months, as people sought the reputed beneficial effects of the thermal springs, and, by 1825, there opened the first structure that could be considered a hotel. By the early 1830s, the springs were proving a major attraction, and, in 1832, Congress reserved the area now known as Hot Springs National Park for federal use, exempting it from settlement. When the town of Hot Springs incorporated in 1851, it was home to two rows of hotels, along with the bath houses and the usual concomitant businesses, and the city attracted not only seekers of leisure but also numerous invalids hoping to find relief in the area’s thermal waters.

By 1860, the number of slaves in Hot Spring County was 613, just over ten percent of the population total of 5,635. Many slaves were employed at the hotels of Hot Springs, and even one hotel advertised that its warm baths were available for “invalid Negroes,” who would then be shipped back to their owners after treatment.

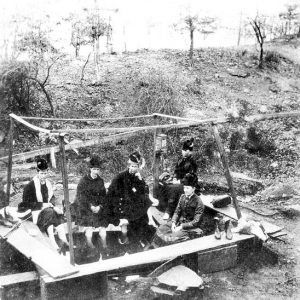

Civil War through Reconstruction

In 1862, when Governor Henry Massie Rector feared that Little Rock (Pulaski County) might be captured by Union troops, he relocated the state records to Hot Springs. From May 6 through July of that year, Hot Springs served as the state capital. The Confederate state government then returned to Little Rock, relocating to Washington (Hempstead County) the following year when Union troops finally did advance upon and capture Little Rock. Hot Springs was never occupied by Union troops and largely escaped the violence of the war save for two minor skirmishes that occurred on February 4, 1864.

Though what was then the Hot Springs Reservation was protected from settlement in the 1830s, settlement and construction occurred near the springs nevertheless. Both before and after the Civil War, three claimants used various legal means to establish ownership of the property. The complicated situation included acts of Congress in 1870 and in 1877, as well as a case (Rector v. United States) that was finally decided by the United States Supreme Court in 1876. Benjamin F. Kelley was appointed by Congress in 1877 as the first superintendent of the reservation.

Kelly initiated a number of engineering projects, allowing private owners to convert the previously ramshackle downtown bathhouses into a row of attractive buildings built in the Victorian style; this, combined with the city receiving a rail connection from what would eventually become the Rock Island Railroad in 1875, transformed Hot Springs into a cosmopolitan spa that would attract visitors from across the nation. The luxurious Arlington Hotel was also completed in 1875 and was, at the time of its completion, the largest hotel in the state. It was built by businessman Samuel W. Fordyce and others who invested heavily in Hot Springs.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

Not only did African Americans have access to employment in Hot Springs, they also had access to the same sort of bathing facilities that attracted wealthy whites to the area. In 1878, the federal government established a simple frame building over what was popularly known as the “mud hole” spring in order to service the poor, who could bathe there for free. Initially, the site, known as the Government Free Bathhouse, was open to all regardless of gender or race. A new brick building was erected in 1891, but it was remodeled in 1898 to provide for racial and gender segregation, though all still had equal access. Until the bathhouses were desegregated in 1965, a number of bathhouses operated that were devoted to a black clientele.

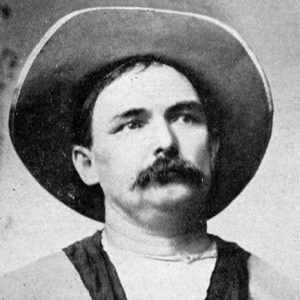

In the early 1880s, there occurred a longstanding conflict for control of local gambling revenues between Frank Flynn and the forces of rival James K. Lane and his chief hired gun, S. A. Doran. Known as the Flynn-Doran War, this rivalry culminated in a February 9, 1884, shootout that left several dead and wounded.

In 1886, the Chicago White Stockings baseball franchise began spring training in Hot Springs. Other teams soon followed suit, and the city continued to serve as a major site of spring training until the 1920s, by which time the franchises had moved to places with warmer climates in the winter such as Florida and Arizona.

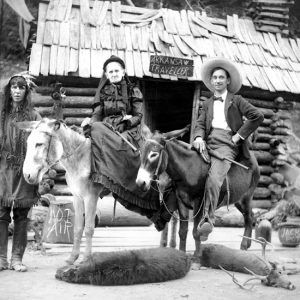

In 1887, the Army and Navy Hospital, the first combined general hospital treating patients from both the U.S. Army and U.S. Navy, opened in downtown Hot Springs. It was the first hospital of its kind in the nation and specialized in arthritis and other ailments that were frequently treated with therapeutic baths. One of Hot Springs’ most popular tourist attractions, Happy Hollow, began in 1888 as a studio that specialized in humorous photographs. The studio remained in operation until the 1940s. The oldest surviving structure in what has become known as Bathhouse Row is the Hale Bathhouse, which dates from 1892–93; the others are early-twentieth-century constructions.

The Hot Springs Normal and Industrial Institute, also known as Mebane Academy, was established in the 1890s and lasted until the 1920s, providing education for African Americans.

An 1895 outbreak of smallpox resulted in negative headlines about Hot Springs across the nation. In 1899 a gunfight broke out between the Hot Springs Police Department and the Garland County Sheriff’s office over which law enforcement agency would profit from the illegal gambling rampant in town.

Thomas Cockburn’s Ostrich Farm was a popular destination when it opened in 1900, and it continued to operate until 1953.

Early Twentieth Century

Thoroughbred horse racing started in Hot Springs with the construction of Essex Park in 1904, although less formal horse racing had frequently occurred in the nineteenth century. The following year, Oaklawn Park (now Oaklawn Racing Casino Resort) opened, and it was soon the only racing venue in the city. However, a state law prohibiting betting on horse races was passed in 1907, and the park closed, though it was used for other purposes, including an early Arkansas State Fair. The track reopened and closed a number of times in the coming years.

The early twentieth century was a time of great construction and destruction in Hot Springs history. Institutions related to health continued to thrive. The Crystal Bathhouse opened in 1904 for use by African Americans, and various owners struggled financially to keep it open during the years that followed. The Levi Hospital was founded in 1914 and continues to operate today, offering mental and physical therapy including rehabilitation therapy in the hot springs of the local national park. The United States Public Health Service (USPHS) opened the first ever federally run venereal disease clinic in Hot Springs in 1921. However, the community also suffered a number of setbacks. A fire in 1905 killed as many as twenty-five people and destroyed nearly 400 buildings. Another in 1913 destroyed a significant portion of the city’s tourist district, including the Crystal Bathhouse.

On December 26, 1910, Oscar Chitwood was murdered at the Garland County Courthouse. The deputy sheriffs who had him in custody claimed that, while they were transferring Chitwood, a mob attacked and killed him, but their story quickly fell apart. Deputies John Rutherford and Ben Murray were put on trial for murdering Chitwood, but despite significant evidence of their guilt, they were acquitted. June 19, 1913, Will Norman, an African American, was lynched after reportedly attacking the fourteen-year-old daughter of his employer, Judge C. Floyd Huff. According to the newspaper account, approximately 5,000 people turned out to watch or participate in the lynching. Though the black population of the city dropped by the time of the next census, perhaps in response to the lynching, by 1930 it had recovered and included an established middle class. The lynching of Gilbert Harris in 1922 is considered the last lynching to have taken place in the area. Hot Springs was also the site of two legal executions, that of an African American teenager, Harry Poe, in 1910 and Clarence Schumann in 1913.

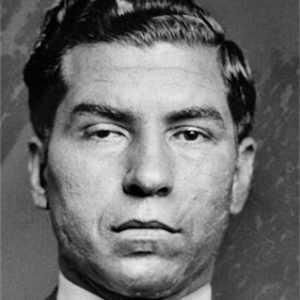

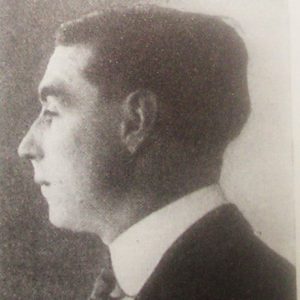

Leo McLaughlin was elected mayor in 1926 and fulfilled a campaign promise to run Hot Springs as an “open” town, one where gambling was permitted by local authorities. Illegal gambling had long been a staple of life in Hot Springs, but the McLaughlin administration carried this to a new level. McLaughlin also oversaw an extensive political machine in Hot Springs that employed rampant voter fraud in order to deliver support to favored candidates. During his twenty-year reign, the city became a haven for numerous underworld figures, including Owen Vincent “Owney” Madden and Charles “Lucky” Luciano. Even Al Capone was a regular visitor to the city. The Southern Club was one of the favored hangouts for many of these gangsters. The relationship local authorities had with these mob figures occasionally put it at odds with state and federal government. Writer Shirley Abbott has penned three memoirs that relate to growing up in this period of Hot Springs’ history, including The Bookmaker’s Daughter.

In 1928, the Interstate Orphanage was built with donations of funds and volunteer labor. It was sustained through philanthropist efforts and today continues to help disadvantaged youth as the Ouachita Children’s Center.

In 1929, Arkansas Power and Light (AP&L) under the leadership of Harvey Couch, which had previously built Remmel Dam along the Ouachita River in Hot Spring County to generate electricity, began construction on Carpenter Dam. The project was completed two years later and immediately proved a boon to the local economy. Carpenter Dam impounds the 7,200-acre Lake Hamilton along the southern and southwestern portions of the city. Numerous tourist enterprises and housing developments have emerged along the shores of Lake Hamilton.

Marquette Hotel and Park Hotel were both opened in 1930 and enjoyed popularity in the 1930s and 1940s; they are both now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Klein Center (now known as the Green Elf Court) was built in the late 1930s and is also listed on the National Register, as is the Hot Springs National Guard Armory. The Chewaukla Mineral Springs Co. incorporated on February 8, 1938, and sold its allegedly medicinal “sleepy water” across the United States.

The arrest of Joseph George Strecker, a restaurant owner, in Hot Springs for alleged membership in the Communist Party led to the U.S. Supreme Court case of Kessler v. Strecker, in which the federal government tried to justify the deportation of Strecker. This was not the only noteworthy Supreme Court case to come out of Hot Springs. Many wealthier African Americans traveled to Hot Springs for vacation during the days of segregation. The U.S. Supreme Court case of Mitchell v. United States (1941) was, in fact, precipitated by the only African American in the U.S. Congress at the time, Representative Arthur Wergs Mitchell of Illinois, who was traveling to Hot Springs for vacation and forced out of first-class accommodations after his train crossed into Arkansas. In the city, there was a “Black Broadway” along Malvern Avenue where many famous musicians played.

World War II through the Faubus Era

Hot Springs experienced some industrial development as well during the World War II years. Bill Seiz, a Hot Springs promoter and business leader, was able to secure from the federal government an aluminum plant between Hot Springs and Malvern (Hot Spring County). He also managed to attract a shoe factory and helped to create the city’s industrial park.

After World War II, several veterans organized to challenge the political leadership of the McLaughlin machine in what came to be known as the GI Revolt, a reform movement that had an impact in several Arkansas counties. In the 1946 election, only reformer Sid McMath was able to win a primary campaign in Hot Springs—that of prosecuting attorney. However, the reformers were able to uncover evidence of massive voter fraud and, as independents, swept the fall elections in Garland County, with Earl Thornton Ricks replacing McLaughlin as mayor.

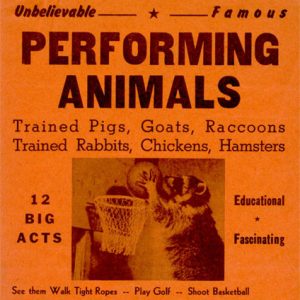

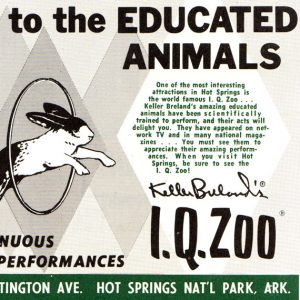

The IQ Zoo opened in 1955 to showcase the accomplishments psychologists Keller and Marian Breland made in the training of animals. It remained a popular destination until its closure in 1990. The Miss Arkansas Pageant regularly took place in Hot Springs starting in 1958; the 2016 pageant was the last in the city.

School desegregation started in 1956 with a high school auto mechanics course, but the conflict over the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock the following year stalled local efforts until 1963, when a limited voluntary desegregation plan was announced.

In 1960, the Army-Navy Hospital was turned over to the state, becoming the Hot Springs Rehabilitation Center, now managed by Arkansas Rehabilitation Services. It was later re-designated the Arkansas Career Training Institute before being slated for closure in 2019.

Modern Era

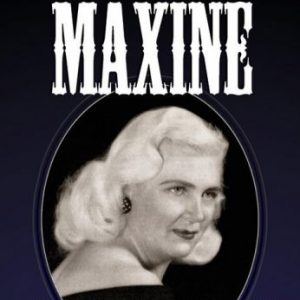

Illegal gambling continued in Hot Springs even after the ouster of the McLaughlin political machine. So notorious was the city’s reputation that closing down gambling in Hot Springs became a major issue in the 1962 gubernatorial race, and the explosion of a bomb in the Vapors casino in January 1963 made the problem of organized crime in the city a widespread concern. Soon after Winthrop Rockefeller took office as governor in 1967, he ordered the Arkansas State Police to crack down on gambling in the spa city. The State Police were able to put an end to illegal gambling in Hot Springs, though it brought them into conflict with local power brokers and even law enforcement officers. The well-known Hot Springs brothel owner Maxine Temple Jones, in prison at the time, disclosed a great deal of information on illegal gambling in return for a full pardon.

Established in 1969 and active for two years, the Council for the Liberation of Black (CLOB) was an activist organization that used peaceful protest to speak against unfair hiring practices and low wages.

Despite the closure of the city’s gambling establishments, as well as the shuttering of the downtown bathhouses from the 1960s to the 1980s, Hot Springs continued to grow, especially as it transformed into a destination for retirees from around the country. The construction of a new convention center made the city attractive to national entertainment tours. Quapaw Technical Institute was established in 1969, and, in 1973, Garland County Community College was created; thirty years later, these were merged into National Park Community College (NPCC), which was renamed National Park College (NPC) in 2015. In 1985, National Park Medical Center was built to replace the old Ouachita Memorial Hospital. The city is also served by the 309-bed St. Joseph’s Mercy Health Center. The twenty-first-century expansion of Hot Springs has been in the direction of Lake Hamilton.

The state’s only public residential high school opened in 1993. The Arkansas School for Mathematics, Sciences and the Arts for juniors and seniors services the state as well as offering interactive video courses over the Internet through the Office of Distance Education. Local businesswoman (and later mayor) Helen Selig played a vital role in securing the school for Hot Springs.

Hot Springs attracted international attention when, in 2007, most of the members of the Monastery of Our Lady of Charity and Refuge, also known as the Good Shepherd Home, which was founded in 1908, were excommunicated by the Roman Catholic Church for heresy.

On February 27, 2014, the Majestic Hotel, a major downtown landmark, caught fire. The hotel opened as a yellow brick building in 1893 and expanded with an eight-story, red brick addition in 1926; the hotel closed in 2006 and stood vacant. The older portion of the building was demolished due to the fire, while the newer section was heavily damaged. After lying empty for more than two years, the structure was demolished in late 2016.

Attractions

Aside from the Hot Springs National Park and Bathhouse Row, there are numerous attractions in Hot Springs. The Hot Springs Music Festival occurs in late spring, while the Hot Springs Documentary Film Institute hosts a ten-day film festival in October each year. The World’s Shortest St. Patrick’s Day Parade began in 2004 and takes place on Bridge Street. The Valley of the Vapors Independent Music Festival (VOV) started in March 2005. Oaklawn Racing Casino Resort hosts the annual Arkansas Derby each spring. The city is also home to Wednesday Night Poetry (WNP), the longest-running weekly poetry open mic series in the nation, and Spa-Con, a major popular culture convention. The Arkansas Walk of Fame was established in 2009 and consists of a walkway made of terrazzo plaques honoring Arkansans who became made nationally recognized contributions to their professions.

An amusement park called Magic Springs (later expanded to Magic Springs and Crystal Falls) opened in 1978. Due in part to the poor handling of the park’s funding, the city opted to issue revenue bonds to make up the shortfall, leading to the 1986 Arkansas Supreme Court decision City of Hot Springs v. Tom Creviston, which determined that revenue bonds could not be issued without voter consent via election; this was later dealt with by a constitutional amendment allowing the practice.

The Hot Springs Country Club is home to the state’s first golf course. The Arkansas Alligator Farm was founded in 1902 and remains a popular attraction. The Mid-America Science Museum features interactive science exhibits and programs geared for young people. The Josephine Tussaud Wax Museum, housed in the former Southern Club, is a noteworthy downtown attraction, as are the Gangster Museum of America, the History of Hot Springs Gambling Museum, and the restored historic headquarters of the Mountain Valley Spring Water company. Garvan Woodland Gardens, a 210-acre botanical garden, opened on the shore of Lake Hamilton in 2002. McClard’s Bar-B-Q became famous nationwide during the campaign and presidency of Bill Clinton. The Winery of Hot Springs offers wine from across the state. The Garland County Public Library is located in a spacious facility on Malvern Avenue.

Recognized historic districts in Hot Springs include: Bellaire Court Historic District, Central Avenue Historic District, Ouachita Avenue Historic District, Perry Plaza Court Historic District, Taylor Rosamond Motel Historic District, Pleasant Street Historic District, Whittington Park Historic District, Cottage Courts Historic District, and Mountainaire Hotel Historic District.

The Medical Arts Building, the Peter Dierks Joers House, the Garland County Courthouse, the Malco Theatre, the Springs Hotel, the Cove Tourist Court, Garland Tower, and Humphrey’s Dairy Farm are also listed on the National Register. Visitors may view Hell’s Half Acre, the Hot Springs Confederate Monument and Confederate Section of the Hollywood Cemetery, fish hatcheries, or purchase a piece of Dryden Pottery. Hot Springs is also home to the Memorial Field Airport and the Ohio Club.

Notable Figures

Bill Clinton lived in Hot Springs as a child, and his boyhood home is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. During his time on the bench, Federal Judge Garnett Thomas Eisele worked for civil rights and prison reform. Pioneering aviator Raynal Cawthorne Bolling was born in Hot Springs.

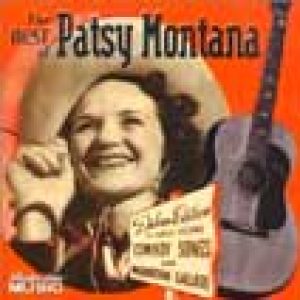

Residents have also included: finance guru Don Rice; philanthropist John Lee Webb; psychologist Mamie Clark; fisherman Carl Cordell; politicians Quincy Hurst and Hiram Whittington; actors Alan Ladd and Billy Bob Thornton; country music singer Patsy Montana; writers Roy Reed, William Whitworth, and Kai Coggin; activists John Riggs and Alfred Smith; judge Timothy C. Evans; illusionist Maxwell Blade; painter Inez Whitfield; architect Irven McDaniel; trailblazing musician and record executive Henry Bernard Glover; and Olympic coach Elliott van Zandt.

John Campbell Greenway was known for his developments in the mining industry and also served in the Spanish-American War.

Ruth Coker Burks provided support for men dying of AIDS during the AIDS epidemic. From the mid-1980s until the mid-1990s, Burk cared for more than 1,000 AIDS patients and carried out an estimated forty-three burials in the local Files Cemetery. Hot Springs native David Hill authored a nationally acclaimed book about his hometown, The Vapors: A Southern Family, the New York Mob, and the Rise and Fall of Hot Springs, America’s Forgotten Capital of Vice. U.S. Representative Bruce Westerman was born in Hot Springs. Artist Longhua Xu, a native of China, is one of the leading lights of the state’s artistic community.

For additional information:

Abbott, Shirley. The Bookmaker’s Daughter: A Memory Unbound. New York: Ticknor and Fields, 1991.

Allbritton, Orval E. Dangerous Visitors: The Lawless Era. Hot Springs, AR: Garland County Historical Society, 2008.

———. Hot Spring Gunsmoke. Hot Springs, AR: Garland County Historical Society, 2006.

———. Leo and Verne: The Spa’s Heyday. Hot Springs, AR: Garland County Historical Society, 2003.

Anthony, Isabel, ed. Garland County, Arkansas: Our History and Heritage. Hot Springs, AR: Garland County Historical Society, 2009.

Bates, Regina A. “‘Our Long Lost Patrimony’: The Belding Family’s Battle for the Spa, 1849–1887.” MA thesis, Arkansas Tech University, 2014.

Blaeuer, Mark. Didn’t All the Indians Come Here? Separating Fact from Fiction at Hot Springs National Park. Fort Washington, PA: Eastern National, 2007.

Bowen, Elliott. “Before Tuskegee: Public Health and Venereal Disease in Hot Springs, Arkansas.” Southern Spaces, October 31, 2017. https://southernspaces.org/2017/tuskegee-public-health-and-venereal-disease-hot-springs-arkansas (accessed October 4, 2022).

———. In Search of Sexual Health: Diagnosing and Treating Syphilis in Hot Springs, Arkansas, 1890–1940. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2020.

———. “Mecca of the American Syphilitic: Doctors, Patients, and Disease Identity in Hot Springs, Arkansas, 1890–1940.” PhD diss., State University of New York at Binghamton, 2013.

Brown, Dee. The American Spa. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1982.

Chmill, Daniel F. “Taking the Waters: A Hydrological History of Health and Leisure in Hot Springs National Park, 1832–1932.” PhD diss., University of Kansas, 2022.

Hanley, Ray. Hot Springs: Past and Present. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2014.

———. A Place Apart: A Photographic History of Hot Springs. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2010.

Hill, David. “How Politics and Religion Handicapped Hot Springs in Its Race to Become America’s Chief Gambling Resort.” Arkansas Times, April 2021, pp. 31–36. Online at https://arktimes.com/news/cover-stories/2021/04/01/how-politics-and-religion-handicapped-hot-springs-in-the-race-to-become-americas-chief-gambling-resort (accessed October 4, 2022).

———. The Vapors: A Southern Family, the New York Mob, and the Rise and Fall of Hot Springs, America’s Forgotten Capital of Vice. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020.

Hot Springs, Arkansas. http://www.hotsprings.org/ (accessed October 4, 2022).

Jones, Ruth Irene. “Hot Springs: Ante-Bellum Watering Place.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 14 (Spring 1955): 3–31.

Kendall, Cassidy. Secret Hot Springs: A Guide to the Weird, Wonderful, and Obscure. St. Louis: Reedy Press, 2025.

Lancaster, Guy, and Christopher Thrasher. The Murder of Oscar Chitwood in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2022.

Leigh, Philip. The Devil’s Town: Hot Springs during the Gangster Era. Columbia, SC: Shotwell Publishing, 2018.

Martin, Bitty. Snake Eyes: Murder in a Southern Town. Lanham, MA: Prometheus, 2022.

Norsworthy, Stanley Frank. “Hot Springs, Arkansas: A Geographic Analysis of the Spa’s Resort Service Area.” PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 1970.

Raines, Robert. Hot Springs: From Capone to Costello. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2013.

The Record. Hot Springs, AR: Garland County Historical Society (1960–).

Shugart, Sharon. The Hot Springs of Arkansas through the Years. Hot Springs, AR: Eastern National Parks and Monuments Association, 1996.

Torrago, Kathryn N. “National Mythmaking in the Valley of Vapors: Imperial Memory at Hot Springs, Arkansas, 1890–1926.” MA thesis, University of New Orleans, 2025.

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Butchie's Drive-In

Butchie's Drive-In Hot Springs Medical Journal

Hot Springs Medical Journal Lynwood Tourist Court Historic District

Lynwood Tourist Court Historic District Opal's Steak House

Opal's Steak House Parkway Courts Historic District

Parkway Courts Historic District Smith, William Young

Smith, William Young Shirley Abbott

Shirley Abbott  Arlington Fire

Arlington Fire  Arlington Hotel

Arlington Hotel  Arlington Hotel

Arlington Hotel  Arlington Hotel Ad

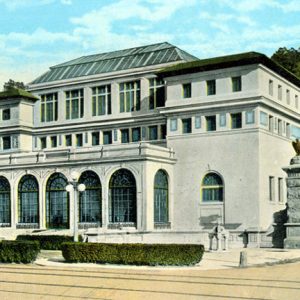

Arlington Hotel Ad  Army-Navy Hospital Building

Army-Navy Hospital Building  Bathhouse Row

Bathhouse Row  Chewaukla Bottling Factory

Chewaukla Bottling Factory  Bill Clinton

Bill Clinton  Corn Hole Spring

Corn Hole Spring  Dryden Pottery

Dryden Pottery  Eastman Hotel

Eastman Hotel  Flood, 1910

Flood, 1910  Samuel Fordyce

Samuel Fordyce  Samuel and Susan Fordyce

Samuel and Susan Fordyce  Garland County Courthouse

Garland County Courthouse  Garland County Map

Garland County Map  Hale Bath House

Hale Bath House  Happy Hollow

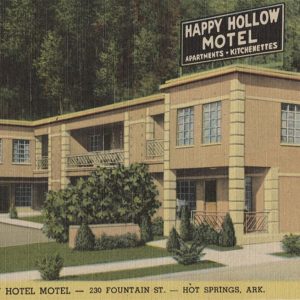

Happy Hollow  Happy Hollow Motel

Happy Hollow Motel  Hot Springs Pin

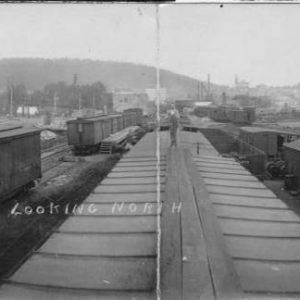

Hot Springs Pin  Hot Springs Rail Yard

Hot Springs Rail Yard  Hot Springs Conductors

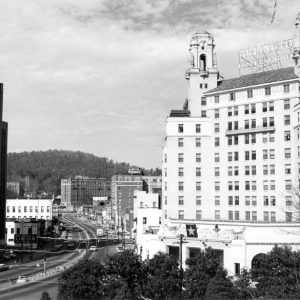

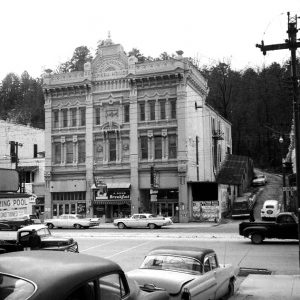

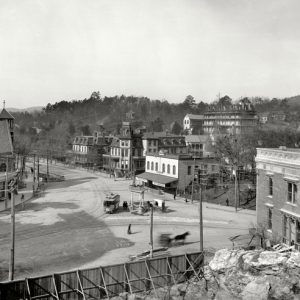

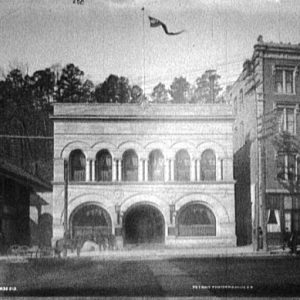

Hot Springs Conductors  Hot Springs Buildings

Hot Springs Buildings  Hot Springs Central Avenue

Hot Springs Central Avenue  Hot Springs Central Avenue

Hot Springs Central Avenue  Hot Springs Fire of 1905

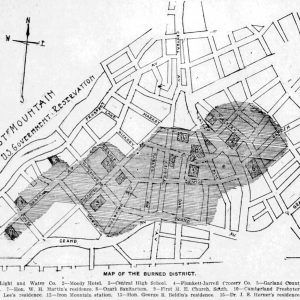

Hot Springs Fire of 1905  Hot Springs Fire of 1913, Map

Hot Springs Fire of 1913, Map  Hot Springs Fire Station and Wagon

Hot Springs Fire Station and Wagon  Hot Springs High School

Hot Springs High School  Hot Springs National Park

Hot Springs National Park  Hot Springs National Park

Hot Springs National Park  Hot Springs Opera House

Hot Springs Opera House  Hot Springs Promotional Brochure

Hot Springs Promotional Brochure  Hot Springs Street Scene

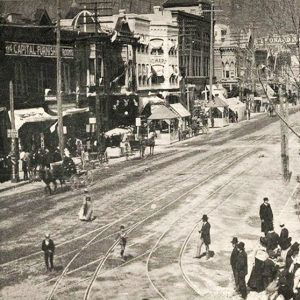

Hot Springs Street Scene  Hot Springs Street Scene

Hot Springs Street Scene  Hot Springs Trolley

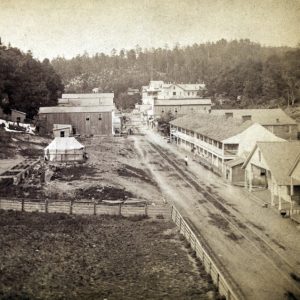

Hot Springs Trolley  Hot Springs, Early Nineteenth Century

Hot Springs, Early Nineteenth Century  "I Want to Be a Cowboy's Sweetheart," Performed by Patsy Montana

"I Want to Be a Cowboy's Sweetheart," Performed by Patsy Montana  IQ Zoo Handbill

IQ Zoo Handbill  IQ Zoo Ad

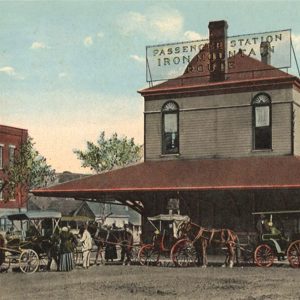

IQ Zoo Ad  Iron Mountain Depot

Iron Mountain Depot  Maxine Jones

Maxine Jones  Josephine Tussaud Wax Museum

Josephine Tussaud Wax Museum  Lanai Towers

Lanai Towers  Mary Lewis

Mary Lewis  "Lucky" Luciano

"Lucky" Luciano  Owen Madden

Owen Madden  Majestic Hotel

Majestic Hotel  Malco Theater

Malco Theater  Maurice Bath House

Maurice Bath House  William Maurice Caricature

William Maurice Caricature  Leo McLaughlin

Leo McLaughlin  Norman McLeod

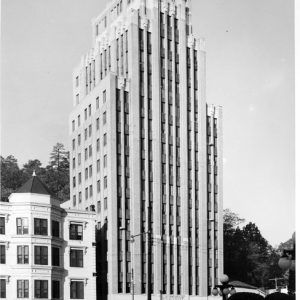

Norman McLeod  Medical Arts Building

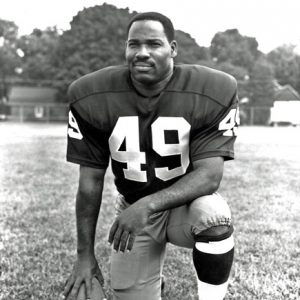

Medical Arts Building  Bobby Mitchell

Bobby Mitchell  Monastery and Order of Our Lady of Charity

Monastery and Order of Our Lady of Charity  Monastery of the Order of Our Lady of Charity

Monastery of the Order of Our Lady of Charity  Mountain Tower

Mountain Tower  Mountainaire Hotel Historic District

Mountainaire Hotel Historic District  Oaklawn Park

Oaklawn Park  Oaklawn Park Racetrack Trading Card

Oaklawn Park Racetrack Trading Card  Pleasant Street Homes

Pleasant Street Homes  Pythian Bathhouse

Pythian Bathhouse  Babe Ruth at Oaklawn Park

Babe Ruth at Oaklawn Park  Bill Seiz

Bill Seiz  Sentinel-Record

Sentinel-Record  Southern Club

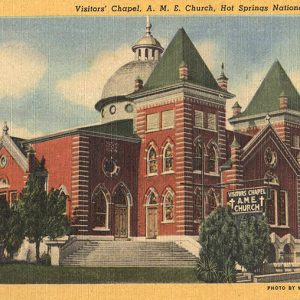

Southern Club  Visitor's Chapel

Visitor's Chapel

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.