calsfoundation@cals.org

Rector v. United States

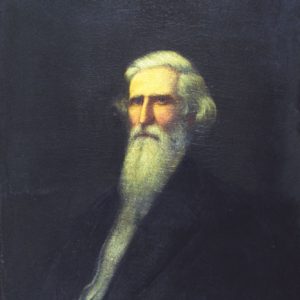

Rector v. United States is a series of court cases initiated by Henry Massie Rector, who was governor of Arkansas from 1860 to 1862, to lay claim to the hot springs now located in Hot Springs National Park in Hot Springs (Garland County). Rector’s claim to the property dated to his father Elias Rector’s survey of the land completed in 1819.

In 1819, Samuel Hammond—a veteran of the American Revolution, former deputy governor of the District of Louisiana, and receiver of public monies of the Land Office of Missouri and Illinois—purchased New Madrid Certificate 467 for $640. Created by the U.S. Congress in 1815, these certificates were awarded to landowners who lost property in the New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811–1812. Certificate 467 was first issued to Francois Langlois, who owned a lot in New Madrid. The certificate awarded him about 170 acres of land in the Missouri Territory. It is unclear if Langlois ever actually held the certificate, as he apparently lived in New Orleans in 1810, Edwards County, Illinois, in 1820, and Randolph, Illinois, in 1830, making it likely that he never returned to New Madrid.

The New Madrid County recorder of land, Joseph Story, obtained Certificate 467 for the supposed price of $260. He in turn sold it to Hammond for $640 on January 4, 1819. Hammond in turn sold half of the interest in the certificate to Elias Rector on February 19, 1819, for $600.

Virginia-born Elias Rector served as a government surveyor in Illinois and Missouri alongside his brother William. Serving in the Illinois militia during the War of 1812, Elias returned to survey work after the conflict. William received an appointment as the surveyor general for Illinois and Missouri in 1816, while Elias was appointed postmaster of St. Louis in 1819.

Elias Rector and Hammond applied for a survey of the land that includes the hot springs in early 1819. James T. Conway completed the survey and delivered the plat and survey to William Rector, who approved and filed them in his role as surveyor general. The claim to the land came into question, however, when the information was sent to the General Land Office (GLO), which would use the information to issue the land patent. The secretary of the treasury adopted two legal opinions issued by the attorney general that stated that only lands surveyed by the GLO at the time of the New Madrid Certificate legislation could be granted. As the land containing the hot springs had not yet been surveyed by the GLO, it could not be given as part of a land patent.

Another congressional act passed in 1822 allowed for previously un-surveyed lands to receive a land patent. Elias Rector did not get a chance to follow through with this process, as he died in Louisville, Kentucky, in August 1822. The claim passed to his son, Henry Rector. Born in 1816, Henry lived in Kentucky with his mother and stepfather after the death of his father. Working in saltworks owned by his stepfather as a teenager, Henry Rector attended school in Louisville for two years before moving to Arkansas in 1835.

Rector hired a surveyor to keep his claim alive. The survey was completed and approved by the surveyor general in early 1838. However, Rector encountered a new problem: A congressional act in 1832 reserved the hot springs and the surrounding sections of land for the exclusive use of the federal government. The GLO refused to issue the patent based on this act. In 1839, the secretary of the interior determined that lands south of the Arkansas River were not eligible for inclusion in the New Madrid Certificates. The following year, Rector received word that this also voided his claim.

Yet another congressional act, passed in 1843, voided the ruling by the Department of the Interior, leading former surveyor and governor of Arkansas at the time James Sevier Conway to push for a patent to be issued to Rector. This effort failed in both 1843 and 1848, when the respective land commissioners rejected the claim. An appeal filed in 1849 to the secretary of the treasury was passed to the attorney general, who ruled that the 1843 and 1848 rejections of the claim were upheld.

Rector finally had a bit of luck in 1850 when the subsequent attorney general ruled that Rector could receive a claim to the land. Before the patent was issued, however, a claim for the land was raised by the heirs of Ludovicus Belding. The Belding claim was based on the residence of the family at the springs no later than 1828 and the Preemption Act of 1830, which allowed settlers to gain title to land on which they farmed in 1829. Earlier efforts by the family to gain title to the springs met the same problems that Rector encountered, including the 1832 act that reserved the springs for the federal government.

The Belding family appealed to the land office register in Washington (Hempstead County) and received a favorable ruling. They were allowed to live on and use the land but did not receive a patent or deed for the property. This case was heard by both the Arkansas Supreme Court and the U.S. Supreme Court, with both finding in favor of the Beldings. The family used this decision to evict other claimants to the land who had constructed buildings near the springs. These included Rector.

Both the election of Henry Rector as governor of Arkansas in 1860 and the Civil War led to a pause in the legal battle over the springs, but with the conclusion of the conflict, the court filings began again. Rector sued in Hot Spring County Chancery Court in 1867 to prevent the Belding family from ejecting him and other claimants. The court ruled in his favor and ordered the Beldings to return any seized property. The Arkansas Supreme Court subsequently ruled against all the claimants in 1870, ruling that none had a right to the land.

Legal proceedings continued. On May 31, 1870, Congress passed another act to bring private claims to the springs to an end. All claims had to be filed within ninety days of the passage of the act. The Court of Claims consolidated all of the cases and made a final ruling in 1874 in favor of the government.

Appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court in October 1875, three claims to the property went before the court. When the three cases were rejected by the court for various reasons related to the timing and authenticity of the claims, this ended the legal fights between the various landowners and the U.S. government, although legislation continued to be passed by Congress related to the hot springs. The various claimants and their heirs continued with lawsuits.

In 1877, Congress passed an act to specify the boundaries of the federal reservation and compensate residents who made improvements within the final boundaries of the reservation, among other actions. With the conclusion of the court cases against the federal government and this act, coupled with the opening of the Diamond Joe Railroad in 1876, major investments began to occur in the city of Hot Springs.

For additional information:

Bates, Regina. ‘“Our Long Lost Patrimony’: The Belding Family’s Battle for the Spa, 1849–1887.” MA thesis, Arkansas Tech University, 2014.

Brown, Walter. “The Henry M. Rector Claim to the Hot Springs of Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 15 (Winter 1956): 281–292.

Shugart, Sharon. “What’s in a Claim?: The Litigious History of the Ouachita Hot Springs.” The Record 53 (2012): 21–54.

David Sesser

Southeastern Louisiana University

Law

Law Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Henry Rector

Henry Rector

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.