calsfoundation@cals.org

Hot Springs National Park

When the United States acquired the “hot springs of the Washita” as part of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the practice of medicine was still in its infancy, but the therapeutic benefits of hot mineral spring water had been well established worldwide for millennia. Over the next twenty-nine years, a few local settlers worked to turn the springs into a privately owned health resort, while others petitioned the federal government to make them accessible for everyone. The latter group prevailed. On April 20, 1832, the United States Congress set aside the area now known as Hot Springs National Park to preserve the springs for public benefit. As the “Government Spa” evolved, it continued to operate for the benefit of the public by setting a range of treatment costs to give rich and poor alike access to the waters and by allowing the destitute to bathe without charge.

A product of complex geological forces, the hot springs flow from the Zigzag Mountains, a small range within the Ouachita Mountains system. Falling rain first percolates through the ground cover, forming carbonic acid as it reacts with carbon dioxide in the soil. Continuing downward through broken chert and novaculite, the acidic water dissolves calcium carbonate, iron oxides, and other minerals. As the water sinks even deeper, its temperature rises, probably because of elemental radioactive decay and gravitational compression deep within the earth. Geologists believe that, at the end of a journey lasting approximately 4,000 years, the water converges between 6,000 and 8,000 feet below the ground just northwest of downtown Hot Springs (Garland County). Here, several large cracks in the earth’s crust provide the water with a quick escape route, and it finally emerges as hot springs on the west side of Hot Springs Mountain.

No one actually knows when humans first began utilizing the hot springs. The archaeological record shows that the first immigrants had arrived in what is now Arkansas by 9500 BC. However, archaeologists have found no artifacts or other physical evidence to show how or if Native Americans used the springs during the millennia they lived in the area. From about AD 800 through early historic times, tribes of the Caddo confederations controlled the area until European diseases decimated the population, forcing survivors south to join related Caddo tribes. As the American westward expansion disrupted tribal territories throughout Native America, several supplanted tribes (most notably the Quapaw and the Choctaw) temporarily occupied the area but did not settle there. The sparse primary documentation from the late 1700s supports the archaeological record to indicate that, by that time, Native Americans visiting the springs were displaced individuals, not intact tribes. For that reason, the few instances of Native American bathing recorded during that time do not necessarily represent cultural traditions.

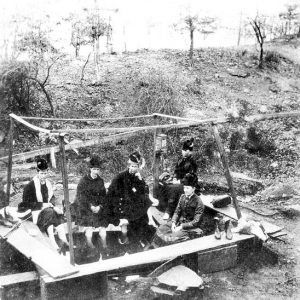

The hot springs area became United States territory in 1803 as part of the Louisiana Purchase. The following year, President Thomas Jefferson commissioned William Dunbar and Dr. George Hunter to lead an expedition to the famed hot springs of the Ouachita River. The party reached the springs on December 9, 1804, and stayed through January 8, 1805, measuring water temperatures, noting the area’s geology, and observing the unique plant and animal life in and around the springs. They also found deserted cabins there, indicating a seasonal use of the springs. The first permanent settler was probably Revolutionary War veteran John Percifull, who came between 1807 and 1809, built a cabin, improved the land, and offered room and board to summer visitors. Visitation and settlement increased over the next twenty years, and a nascent spa emerged.

Quapaw claims to the territory that included the hot springs were extinguished by an 1818 treaty between the two nations, opening the land for legal claims. In 1820, the territorial assembly of Arkansas sought to keep the springs open to the public by petitioning the U.S. Congress to let “sections be granted to the local Legislature, to include all the Hot Springs for the benefit of that watering place.” Nothing was done, and in 1832, the territorial government issued a memorial requesting that the U.S. House of Representatives appropriate funds to build, maintain, and manage a hospital at the springs. In response, Congress passed an act to reserve the hot springs and their environs (2,529.1 acres), guaranteeing that “four sections of land including said [hot] springs, reserved for the future disposal of the United States, shall not be entered, located, or appropriated, for any other purpose whatsoever.” On April 20, 1832, President Andrew Jackson signed the act, exempting the area from settlement. Hot Springs National Park is arguably the oldest of the current national parks in the National Park Service, predating Yellowstone National Park by forty years. Because the area was reserved for federal use, it became known as the Hot Springs Reservation.

The federal government did not fund a hospital until the 1880s, when the first Army-Navy Hospital was built. It did not even make clear provisions for administering the area, and several private citizens eager to develop the springs filed claims to them. After the establishment of the Department of the Interior in 1849, the reservation (originally administered by the General Land Office) was placed under the control of the Secretary of the Interior, who was pressured by Congress to resolve the ownership issue. The controversy continued, occasionally erupting into violence over disputed land, until an 1870 federal statute gave permission for claimants to settle the land title controversy in the Court of Claims, with right of appeal. The claims were subsequently consolidated, and the claimants sued the United States. The Court of Claims ruled in favor of the United States. An appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court in October 1875 resulted in the affirmation of the Court of Claims ruling, vesting title in the United States. In 1877, Congress authorized a commission to establish new reservation boundaries, sell excess lots, tax the thermal water, and appoint a reservation superintendent. General Benjamin F. Kelly—an old friend of railroad magnate, hotelier, and bathhouse owner Colonel Samuel W. Fordyce—was selected to be the first Hot Springs Reservation superintendent. Entrepreneurs flocked in to implement ambitious building and business plans, while the Department of the Interior poured funds into engineering and landscaping projects. In just a decade, the area changed from a rough frontier town to an elegant spa city built around a row of attractive Victorian-style bathhouses, the last ones completed in 1888.

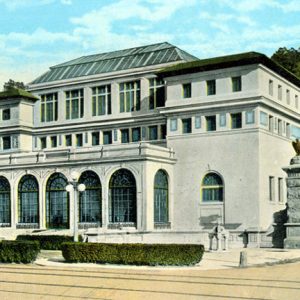

Subsequent medical director Harry Hallock was responsible for many of the changes that form the basis for modern regulations today. By 1923, fire-resistant brick and stucco bathhouses (some magnificently appointed) had replaced all of the deteriorating Victorian structures. On August 25, 1916, Congress established the National Park Service (39 Stat. 535), and Hot Springs Reservation came under its administration. Hot Springs Reservation became Hot Springs National Park on March 4, 1921.

By the 1950s, the area’s bathing industry was in decline, and the eight Bathhouse Row businesses were struggling financially; this was possibly due in part to new medical treatments for conditions such as arthritis, as well as the cessation of illegal gambling in Hot Springs, but spas everywhere in the United States were in decline at this time. In 1962, the elegant Fordyce Bathhouse closed, followed in the 1970s by the Maurice, the Ozark, and the Hale. In 1984, the Quapaw and Superior Bathhouses closed. When the Lamar Bathhouse closed in 1985, only the Buckstaff was still in business on Bathhouse Row.

Bathhouse Row and its environs were placed on the National Register of Historic Places on November 13, 1974. The desire to revitalize downtown Hot Springs led citizens to campaign for adaptive uses of the vacant bathhouses. The luxurious Fordyce Bathhouse, adapted for use as the park visitor center and museum, reopened on May 13, 1989. Hot Springs National Park restored the original bathhouse furnishings or replaced them with authentic substitutes and opened the bathhouses for public tours. Under Josie Fernandez, appointed superintendent in 2004 (and the first woman to hold the position), the majority of the bathhouses became occupied with government agencies or private businesses.

The historic bathhouses form the core of the park’s cultural heritage, but it also maintains several formally landscaped areas of mixed native and exotic species. The row of stately southern magnolia trees in front of Bathhouse Row is probably the best known of these. Other cultural features include fountains, concrete paths, historic hiking trails, paved scenic drives, a former Government Free Bathhouse, a 1912 former medical director’s residence, and a brick Grand Promenade that is a National Recreation Trail.

At around 5,500 acres, Hot Springs National Park includes a surprising variety of natural resources. Although the springs were enclosed by 1901, the National Park Service diverted some of the thermal water in 1982 to form a thermal water cascade that recreates the appearance of a natural thermal spring. The park’s most common topographic features are the rocky mountain slopes and lush creek valleys, supporting mixed stands of oak and hickory interspersed with shortleaf pine on the more exposed slopes and ridge tops. The park is home to at least three rare plant species: a local chinquapin (Castanea ozarkensis), Graves spleenwort (Asplenium gravesei), and a blue-green alga (Phormidium treleasei) that grows wherever the hot spring water is exposed to light and air. A 150-acre stand of shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata) believed to be virgin timber is registered under the Arkansas Natural Heritage Program. Wildlife within the park is typical of the Ouachita Mountains.

The 2010 Hot Springs National Park Quarter was released for circulation on April 19, 2010, the first coin issued in the America the Beautiful Quarters Program.

For additional information:

Carpenter, Kathryn Blair. “Access to Nature, Access to Health: The Government Free Bathhouse at Hot Springs National Park, 1877–1922.” MA thesis, University of Missouri–Kansas City, 2019.

Hanor, Jeffrey S. Fire in Folded Rocks. Hot Springs, AR: Eastern National Parks and Monuments Association, 2003.

Hot Springs National Park (National Park Service). http://www.nps.gov/hosp (accessed April 24,2024).

Rowland, Mrs. Dunbar [Eron O. Rowland]. Life, Letters and Papers of William Dunbar. Jacksonville: Press of the Mississippi Historical Society, 1930.

Shugart, Sharon. The Hot Springs of Arkansas through the Years. Hot Springs, AR: Eastern National Parks and Monuments Association, 1996.

———. “‘What’s a Nice Set of Springs Like You Doing in a Place Like This?’ The Bathhouses at the Hot Springs of Arkansas, 1809–1878.” The Record 44 (2013): 3.1–3.36.

Sharon Shugart

Hot Springs National Park

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.