calsfoundation@cals.org

Military

Arkansas’s military history began sometime after the first Paleoindian hunter-gatherers arrived. Territorial conflicts doubtless occurred at intervals during prehistoric times. The attempt to establish European dominance led to more conflicts, and Arkansas has played a role in all the wars involving the United States. Although physical violence has always been rooted in the state’s popular culture, militarism was slow to take root. In the absence of military schools, Arkansas’s support for the military often reflected a rural economy that lacked economic opportunities for young males, as well as the diligence of service recruiters.

Prehistoric and Territorial Aggression

No evidence documents the first hostile encounters between Arkansas tribes, but excavation at the Late Archaic Crenshaw site in southwestern Arkansas unearthed a female burial (probably pre-Caddoan) accompanied by several skulls without appurtenant parts. One possible explanation is that prisoners were beheaded. Territorial aggression increased greatly with the bow and arrow’s introduction (around AD 600), and archaeological evidence indicates that warfare developed by successive stages, beginning with family and tribal and moving up to the level of complex kingdoms. Its impact was apparent in the Delta region after AD 1200, where dispersed farm hamlets and villages gave way to large fortified towns. The Mississippian bastioned stockades made efficient use of space and were impervious to arrows. Spanish, French, and English stockades later adopted the pattern. In the Ozarks, the Caddo abandoned their settlements in the wake of Osage aggression. Until European-delivered diseases decimated their populations, Indian armies were large, well organized, and consisting of both men and women.

Judging by what is known of tribal practices in this period, captives frequently were enslaved. Partial removal of a captive’s foot or the severing of a tendon would prevent flight but not preclude agricultural labor. Female captives were married off; tribes with diplomatic relations often intermarried.

Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto traversed the eastern and southwestern areas of Arkansas from 1541 to 1543. Supported by Catholic priests, fighting dogs, and armored men on horses, de Soto used terror and torture in ways that seem to have exceeded the rules of engagement. De Soto died in Arkansas, and his men escaped down the Mississippi River followed by the curses and arrows of the natives. The de Soto narratives present an unflattering view of the martial abilities of the Casqui, who lived at a site in present-day Parkin (Cross County), and reflect appreciation of the fortifications of Pacaha on the Mississippi River. The Tula in southwestern Arkansas, probably a Tunican people, were among the strongest opponents de Soto encountered, and they discouraged the Spanish leader from pushing any deeper into the Ouachita Mountains. As tribal size shrunk, the Indian approach to warfare changed to hit-and-run tactics in order to minimize loss of life.

The first French exploration of Arkansas, that of Father Jacques Marquette, Louis Joliet, and a couple of boatmen in 1673, was followed by a larger force led by René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle in 1682, leading to the founding of Arkansas Post in 1686. The post did not get a military garrison until 1721. The post, whose location on the Arkansas River kept shifting because of flooding, became a key location in French Louisiana. The garrison, usually about two dozen men, helped protect trade on the Mississippi. Ongoing wars between the French and their Quapaw allies against the Chickasaw prompted a major French offensive in 1731. Unfortunately for his army, Major Pierre D’Artaquette did not wait for Governor Jean Baptiste Le Moyne Bienville’s army and was badly defeated by the Chickasaw. More than 100 of the 140 French in the command were killed; the major and thirteen captives were roasted alive. Bienville tried in 1737 and 1738 to renew the war, but bad weather grounded the campaign. Warfare continued, and Chickasaw leader Payah Matahah crossed the Mississippi, attacking the post on May 10, 1749. He was wounded in the assault, and while the post was partly burnt, the French repulsed the attack.

In 1762, the Spanish succeeded the French at what became Post de Charles Trois in 1779. French officers remained until 1770, and the garrison was small. During the Revolutionary War, the Spanish created a militia of French settlers and Americans who had moved to the area to avoid the war. Spanish support for the French in the war for U.S. independence led Tory leader James Colbert to attack the post on April 17, 1783. In the westernmost battle of the Revolutionary War (and one of two west of the Mississippi River), Colbert failed to take the fort and, after a daring counterattack, was driven back to his boats. Nothing of military importance happened after this battle, but Spain tried to frustrate U.S. development by seizing illegally the Chickasaw Bluffs on the U.S. side of the Mississippi River and establishing an outpost called Camp de la Esperanza. After the 1795 Treaty of San Lorenzo (Pinckney’s), the post moved across the river to become the future town of Hopefield (Crittenden County), a rival to Memphis that arose on the third Chickasaw Bluff.

Organized Militia

In 1804, after the Louisiana Purchase, the Americans established Fort Madison at the post but abandoned it during the War of 1812. American law required the organization of a militia, and the first body was created in 1806. A company of infantry and one of light cavalry constituted Arkansas’s local armed forces.

Once Arkansas became a separate territory in 1819, its governors were instructed to implement a more effective militia. The federal law of 1792 required training for all men ages eighteen to forty-five, but the dispersed population was apathetic. Active organization of the militia began with George Izard, second territorial governor. A regulation book was published in 1826, but resistance to training and serving was strong. Because Arkansas bordered the Mexican province of Texas as well as the Indian frontier, militia companies and Jesse Bean’s ranger force saw occasional service in 1832–1833 and 1836–1837. Izard also used militia appointments to honor political allies Ambrose H. Sevier and Chester Ashley. In time, most leading Arkansas politicians attained the rank of colonel and, despite almost never actually serving, kept the title unless they gained a higher one.

Arkansas played almost no role in the War of 1812, but the complex process by which the federal government decided to use Arkansas’s western lands to resettle southeastern Indian tribes led to the building of the first Fort Smith (Sebastian County) in 1817. Abandoned as too small in 1824, it was reestablished in 1831, abandoned in 1834, and finally reactivated in 1838. The fort served as the central point for the feeble federal control over Indian Territory that ended only when it attained statehood as Oklahoma in 1907.

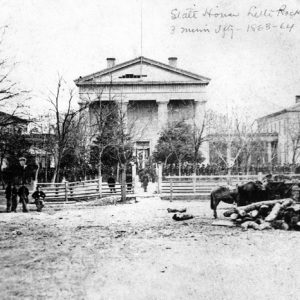

In Little Rock (Pulaski County), a Class Three federal arsenal went up in 1840 and eventually included twenty-eight buildings. In 1880, the Little Rock Battery, as it was then styled, would be the birthplace of a famous general, Douglas MacArthur. The arsenal was closed in 1890 when a property exchange gave the site to the city of Little Rock in return for land north of the Arkansas River that became Fort Logan Roots.

Mexican War

Arkansas was a ten-year-old state in 1846 when the Mexican War began. The state contributed a regiment whose poor discipline and rape and robbery of civilians led to its being nicknamed the “Mounted Devils.” At the Battle of Buena Vista, its colonel, Archibald Yell—the charismatic former congressman and governor—died at the head of some of his troops who followed him in an ill-fated charge. Controversy about the Arkansas soldiers’ behavior in the battle resulted in a duel between Captain Albert Pike and Yell’s successor, Colonel John Selden Roane, in which neither was injured. But, by participating in a duel, Roane became technically ineligible to be governor despite being elected in 1850 by a large popular vote.

Politically, the war benefited others besides Roane. Major Solon Borland captured a U.S. Senate seat, and Captain Christopher Columbus Danley unseated Elias Conway to become state auditor. Danley bought the Arkansas State Gazette and Democrat newspaper from William E. Woodruff in 1853, owning it until he died in 1865.

Although violence was pronounced in Southern life, little military interest could be found in antebellum Arkansas. At Tulip (Dallas County) in the 1850s, the Arkansas Military Institute existed, but almost nothing is known about it.

Civil War and Reconstruction

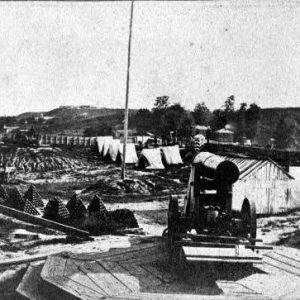

The Civil War profoundly affected Arkansas. Before the war formally began, shooting had stopped boats on the Mississippi. Also, in February 1861, an armed force estimated to number in the thousands descended on the capital threatening to seize the arsenal. The crisis was resolved when Captain James Totten agreed to evacuate the premises and Governor Henry M. Rector assumed responsibility for the weapons. The Confederates dispersed the weapons to state regiments and used the arsenal until September 1863, when the city fell to General Frederick Steele’s Union army.

After the state convention passed an act of secession on May 6, 1861, the Arkansas army took shape independent of the existing militia structure. Not trusting Rector, the convention assigned the war power to a military board of which the governor was one of three members. The military board at first oversaw the Arkansas army and later collected supplies for Confederate soldiers. About half of the Arkansas army saw service at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek (Oak Hills) on August 10, 1861. Only eighteen men from that section transferred to the Confederate army that fall. More than half of those on the eastern side of the state joined the Confederate service after General William J. Hardee arrived in the state.

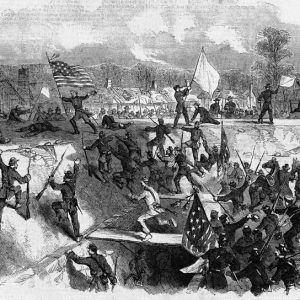

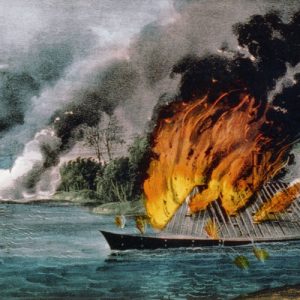

When Union forces under General Samuel Curtis threatened Arkansas in the spring of 1862, the Confederacy sent General Earl Van Dorn to assume command. Van Dorn lost the Battle of Pea Ridge (Elk Horn Tavern) on March 8, 1862, and subsequently took the army east of the Mississippi River. After restructuring his supply line from Rolla, Missouri, Curtis headed south to Batesville (Independence County). General P. G. T. Beauregard sent General Thomas C. Hindman to Arkansas. Hindman put Arkansas under martial law and endeavored to create a modern war state. He legalized guerrilla warfare and created an army by ignoring all the provisions of the draft law. A Union naval detachment sent up the White River with food for Curtis suffered a serious loss when a Confederate cannon shot hit the Mound City’s boilers. Low water also prevented Curtis from receiving supplies. The Action at Whitney’s Lane near Searcy (White County) marked his farthest advance. Then Curtis escaped to Helena (Phillips County), liberating slaves and destroying property. Confederates at the Action at Hill’s Plantation failed to stop him. With Curtis isolated at Helena, a massive public outcry arose against Hindman. General Theopolis Hunter Holmes took charge of the Trans-Mississippi Department, but Hindman remained field commander until losing the Battle of Prairie Grove on December 7, 1862. The Confederate-held Arkansas Post fell in January 1863, and Holmes lost the Battle of Helena on July 4, 1863. In September, Union forces seized Little Rock and Fort Smith.

Military engagements continued in 1864 when Steele, who was supposed to join General Nathaniel Banks in Louisiana, got no farther than Camden (Ouachita County). Union forces lost engagements at Poison Spring on April 18, 1864, and Marks’ Mills on April 25, 1864, before retreating to Little Rock. Poison Spring was marked by atrocities against Black Union troops. The Confederacy failed at the Engagement at Jenkins’ Ferry (April 30, 1864) to cut off that retreat. Most of the state disintegrated into guerrilla warfare, with much suffering by the civilian population. Union control was limited to Fort Smith, Little Rock, and Pine Bluff (Jefferson County). Even the western segment of the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad that ran from DeValls Bluff (Prairie County) to the capital was attacked intermittently. In the fall of 1864, General Sterling Price passed through the state unopposed on his ill-fated Missouri invasion.

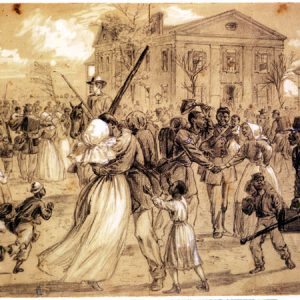

Union troops stayed in Arkansas in the early days of Reconstruction. Violence continued. The new Republican governor, Powell Clayton, a former Union army colonel, reorganized the militia to fight not only outlaw bands but also the military arm of the Democratic Party, the Ku Klux Klan. Clayton was almost the only Republican governor to force the Klan to back down. After open warfare in eastern and southwestern Arkansas, a formal disbanding and amnesty brought a modicum of peace to most of the state. Nevertheless, localized violence continued to erupt. Among the dead were Republican congressman James Hinds and former general Hindman. Paramilitarism returned in 1874 during the Brooks-Baxter War as both of the purported governors, Elisha Baxter and Joseph Brooks, had armed forces. Across the state, more than 200 casualties resulted from warfare between their respective militias. Violence continued after 1874, as with the Pope County Militia War. In counties with equal numbers of Union and Confederate veterans, county civil wars erupted. Governors called out the militia in Perry and Scott counties in what are called the Perry County War and the Waldron War. In 1879, the legislature retaliated against Governor William Read Miller by abolishing the office of adjutant general, the longstanding title of the state’s militia commander.

In the critical election of 1888, when agrarians challenged the Democratic establishment, armed bodies of white citizens prevented African Americans from voting in Crittenden and other largely Black counties, establishing white control that lasted seventy-five years.

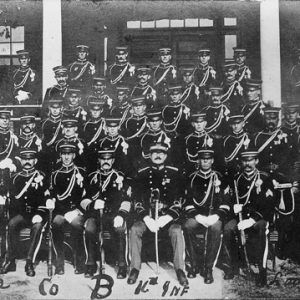

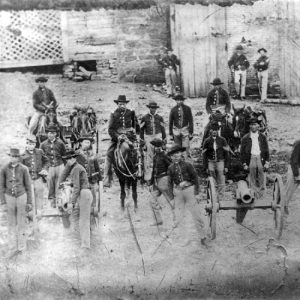

As the militia declined in significance as governors had no interest in preventing violence against African Americans and Republicans, Arkansas sported two highly praised military drill units, the Quapaw and McCarthy guards, which competed against other elite national units. Their success inspired the creation of the Hurley Guards at Newport (Jackson County), the Valley Guards at Hot Springs (Garland County), and soon-to-be disbanded Gracie Guards at Pine Bluff.

Spanish-American War

Arkansas’s next military event was the Spanish-American War. Federal law prevented President William McKinley from using the militia outside the United States, and Arkansas’s militia was too poorly organized to respond, anyway. Governor Dan W. Jones called on companies from all over the state to meet the president’s call for two regiments. The First Arkansas Regiment mustered at Camp Dodge in Little Rock under the command of Colonel Elias Chandler, who had been the military commandant at the Arkansas Industrial University (now the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville). The Second Arkansas Regiment mustered at the same site with Virgil Y. Cook of Batesville commanding. Twenty-five percent of both groups of volunteers failed the physical examination.

After mustering, the regiments left for Camp Thomas at Chickamauga Park in Tennessee. Conditions were terrible, and fifty-four of Arkansas’s 2,000 volunteers died. Neither unit saw combat, but returning “veterans” brought back new strains of smallpox that created a major public health crisis. Colonel Theodore Roosevelt’s acclaimed Rough Riders, who saw combat in the assault on Santiago, included Lieutenant John C. Greenway of Hot Springs, who was cited for gallantry.

About fifty Arkansas soldiers reentered the army for service in the Philippines. The United States had little trouble defeating the Spanish, but the natives wanted independence. The army responded with violence, and at least one Arkansas soldier, writing to the Fort Smith Elevator newspaper, indicated that the soldiers did not like this work and thought the islands should be given their independence.

New Entities

The broader military problems associated with the United States’ elevation to a world power resulted in a 1903 federal law giving more direction and money to state militias. The term National Guard became mandatory in 1916 and reflected a new level of professionalism. Also in the 1916 legislation was the creation of the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC). Some military instruction had been mandated in land grant institutions (such as the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville) since the passage of the federal Morrill Act in 1862. New legislation regularized programs and expanded the program to other schools. Students generally had to attend classes and drill, and participants graduated as officers.

Arkansas supplied 1,208 troops in support of the U.S. invasion of Mexico in 1916. Stationed in Deming, Texas, none of the Arkansas troops left the country or were in combat.

World War I

U.S. involvement in World War I began April 6, 1917, and the National Guard units were immediately called up and transferred into the U.S. army. The pre-1917 First Regiment became the U.S. 153rd Infantry, although a machine gun battalion went into the 141st. The old Second Regiment became the 142nd Field Artillery Regiment. The third regiment was split between the 154th and 141st.

There was great fear of German activities, and the newly organized National Guard unit successfully captured a radio receiver on Mount Magazine; however, it had been left there by the U.S. Geological Survey. The search for a German flag seen flying near Bauxite (Saline County) proved futile. The unit also attempted to enforce the draft. Armed resistance occurred in Searcy, Polk, and Cleburne counties and was associated with a group then called the Russellites (after founder Charles T. Russell), known after 1931 as the Jehovah’s Witnesses, in the last of these. In Cleburne County, thirty untrained National Guardsmen, supported by two Vickers machine guns and various home guard units numbering about 200 soldiers, failed to find the eight draft dodgers, who eventually turned themselves in. Some persecution of German families took place, but the state’s leading German-language newspaper, the Arkansas Echo, survived.

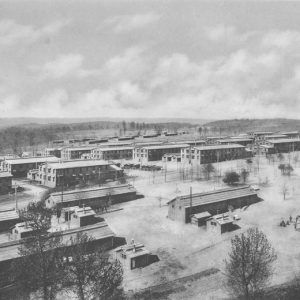

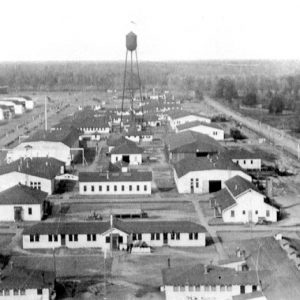

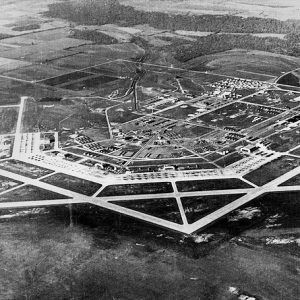

Arkansas had two training bases: Camp Pike in North Little Rock (Pulaski County) opened in the fall of 1917, housing up to 100,000 men, and a second camp trained black soldiers. Also, a Wisconsin-class battleship was named after the state. An important air training station, Eberts Field, was established in Lonoke County and was named for Captain Melchior McEwen “Ike” Eberts, a Arkansas West Point graduate who had died in an airplane crash.

A total of 8,732 males in the state evaded the draft or deserted. To support morale, the federal government created the Arkansas Council of Defense, with a separate Colored Auxiliary Council for African Americans. Projects included attempts to shut down pool halls and to mobilize the loafers and idlers into the war effort. About 72,000 troops, including 1,400 women, served in the war. Included in that number were 17,544 Black soldiers. Douglas Robinson of Clarendon (Monroe County) was the first Black soldier to receive a commission (as second lieutenant). At least one major racial incident erupted at Camp Pike on March 5, 1918; disrespectful white behavior was the apparent cause, and Black soldiers were punished. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) organized its first chapters at Little Rock and Fort Smith thereafter.

Herman Davis of Manila (Mississippi County) and Oscar Franklin Miller were on General John S. Pershing’s list of 100 heroes. Aviators included Captain Field Kindley and John MacGavock Grider. Grider’s posthumously published but much edited diary, War Birds: Diary of an Unknown Aviator (1929), became standard reading after World War I. The war’s end coincided with the 1918 flu epidemic that claimed more lives worldwide than the war and hit Camp Pike especially hard.

After the war, the National Defense Act of 1920 reorganized the militia into the modern National Guard. Camp Pike was turned over to the guard, and new rules took effect. Arkansas soldiers were part of the Thirty-fifth Division of the Fourth Army Corps. Arkansas was home to the 206th Coastal Artillery, an ambulance company, and the 154th Observation Squadron. The 154th “aero squadron” had been created during the war but was disbanded in 1919. Reactivated in 1925, it received an award for its service during the Flood of 1927; Adams Field, Little Rock’s airport, was named for George Geyer Adams, a member this unit. The guard performed many services, especially during the Flood of 1927. In 1937, Camp Pike was renamed for former Senator Joseph T. Robinson. The ROTC was expanded in this period. The first programs went to the state’s white colleges. The state’s first public Black college—Arkansas Agricultural, Mechanical, and Normal College (now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff)—got a program despite white opposition only after World War II began.

World War II

Although the United States was neutral when World War II began, Congress in 1940 narrowly passed peacetime draft legislation, and all Arkansas National Guard units were mobilized by January 1941. The state experienced a foretaste of war when in 1941 the U.S. military held extensive maneuvers in southern Arkansas. At Prescott (Nevada County), the military press corps “seized” the office of Nevada County Picayune and issued a propaganda sheet from the “captured” office.

Direct U.S. involvement followed the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Although Arkansas had little seniority in Congress, a few smaller wartime facilities came to Arkansas, including the Southwestern Proving Grounds near Hope (Hempstead County), an air force base at Walnut Ridge (Lawrence County), Camp Chaffee, an incendiary munitions factory at Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), and an ordnance plant at Jacksonville (Pulaski County). Norfork Dam was a wartime priority, as was building an aluminum plant at Magnet Cove (Hot Spring County).

The war also triggered several racial incidents. Open warfare at Gurdon (Clark County) between white people and the Black Ninety-fourth Engineers Battalion almost erupted when a highway patrolman told the unit’s white officers that Black men could not sing in the presence of whites. The fact that black troops were used to guard German and Italian prisoners of war, who could eat in the state’s cafes when the soldiers could not, compounded resentments that surfaced when Little Rock police killed an off-duty sergeant, Thomas B. Foster, from the Ninety-second Engineers Battalion after a confrontation. Foster was shot five times, but while the Negro Citizens Committee of Little Rock called the shooting a “bestial murder,” an all-white grand jury acquitted the police officer. The city did agree to hire some Black policemen, but they could not touch whites, nor were they eligible for pension benefits.

Arkansas workers were recruited vigorously for wartime manufacturing, and more than ten percent of the population left. Women from Fulton County went to the Gulf Coast shipbuilding factories. Other common destinations included Wichita, Kansas; the Rock Island Arsenal in Illinois; Michigan; and California.

Arkansas National Guard soldiers went to a polar extreme in the Aleutian Islands, protecting the country’s northernmost flank from the Japanese in what was later called the “Williwaw War.” Colonel William O. Darby’s elite rangers took part in the North Africa and Italian campaigns. The 154th Observation Squadron grew to consist of nine units and went to North Africa and Italy. Arkansas editor Paul (Pete) Coughlin became nationally famous as the “Sergeant York of the air” after he and his observer captured about 150 Italian prisoners from the air during the landing at Scoletti, Italy. Draftees from Arkansas saw service in the Far East and Europe and at sea.

Post World War II

Returning GIs took part in a movement called the GI Revolt. During the war, the U.S. government had conducted extensive educational campaigns contrasting Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan with America’s supposed democratic freedoms. GIs found themselves confronting corrupt county machines. War hero Sid McMath led a successful revolt in Garland County, and GIs in Crittenden County built voting booths for privacy. McMath’s election as governor in 1948 was in large part due to the election skills the GIs learned in county struggles. One McMath supporter with a later career in government, as well as a recorder of his wartime experiences, was Orval Faubus (This Faraway Land, 1971).

The rapid military shutdown after the war did not last. In 1947, the Air National Guard became independent. Congress restored the peacetime draft in 1948 and, in 1951, lowered the draft age to eighteen and a half. In rural Arkansas, rather than wait to be drafted, many males entered the army after high school. Some made careers in the military, but almost none returned to farming and few to the state.

Korean War

On June 25, 1950, North Korea invaded South Korea. Again the 154th Observation Squadron was sent out of the country. National Guardsmen were recalled to service, and even after the war, the emerging Cold War affected Arkansas. The main physical benefit was the construction of the Little Rock Air Force Base at Jacksonville (Pulaski County) partly on the grounds of the former ordnance plant.

Desegregation of Little Rock Central High School

Arkansas’s defining military moment in the twentieth century began on September 2, 1957, when Governor Faubus announced that National Guard soldiers would take their places at Little Rock’s Central High School and Horace Mann High School (the city’s Black school) “to carry out their assigned tasks.” Not until the next day did Americans learn that their task at Central was to prevent Black students from entering. A federal judge ordered Faubus to remove the troops. A crowd visited the unguarded school on September 23, leading school officials to send all the students home. President Dwight Eisenhower responded the next day by sending in the 101st Airborne Division from Fort Campbell, Kentucky. In November, federalized National Guard units replaced the paratroopers. The segregationist press claimed troops spied on girls in the showers, and some members of the Little Rock Nine believed the guardsmen did little to prevent harassment.

Vietnam War

Meanwhile, the nation was sliding into the Vietnam War. No National Guard units were involved, so Arkansas was primarily concerned about draft policies and the war’s correctness. Future governor and president Bill Clinton was one student not eager to be drafted, and his correspondence with Colonel Eugene Holmes concerning admission to the University of Arkansas ROTC program was later used against him politically. The war’s end coincided with replacement of the draft with a lottery system. Opposition to the war came from President Lyndon Johnson’s former ally, Senator J. William Fulbright of Arkansas. Although a national hero to war opponents, Fulbright was called “Half Bright” and accused back home of being a communist. Lingering resentment helped bring his defeat in 1974 by Governor Dale Bumpers.

Opposition to the war was considered unpatriotic, and colleges were hotbeds of opposition. Mixed in was a youth revolt featuring long hair (soldiers had their heads shaved in basic training), the Beatles, and drugs. Drug use was common in the military in Vietnam. The war, on one hand, helped humanize the plight of soldiers, but the losing cause produced few heroes.

Post Cold War

The end of the Cold War resulted in a scaled-down professional army but one that still provided opportunities for Arkansans after high school. Despite the ambivalent legacy resulting from the Vietnam War, support for the military still ran deep.

The first post–Cold War military engagement involving Arkansas was the Persian Gulf War in 1990. Arkansas contributed 3,400 service personnel. The Thirty-ninth Infantry Brigade, one of fifteen “enhanced” brigades with the most modern equipment, spent time in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia protecting Patriot missile sites. From the end of Operation Desert Storm to the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States, more than 1,200 soldiers and airmen were called to duty in Bosnia, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Germany, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Diego Garcia, and the Sinai peninsula. More than 4,500 soldiers and airmen were called to active duty after September 11, serving in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other locations. The Thirty-ninth accounted for 2,805 of those and saw service for a year in and around Baghdad, Iraq, before returning in March 2005.

The stresses on the National Guard in Iraq reflected nationwide problems in recruitment and retention. One was the projected closing of some of the state’s seventy-five armories. Another worry was the Little Rock Air Force Base, which had a $600-million impact on the state and indirectly created more than 3,000 jobs. A 2005 base-closing plan would have added jobs there but imperiled the 188th Fighter Wing’s base at Fort Smith. An uncertain military future lay ahead as National Guard recruitment fell short and a small professional army struggled to fight all the wars its leaders envisioned.

For additional information:

Arkansas National Guard. https://arkansas.nationalguard.mil/ (accessed June 30, 2023).

Arnold, Morris S. “The Soldiers of France in Colonial Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 80 (Winter 2021): 403–435.

Christ, Mark K. “All Cut to Pieces and Gone to Hell”: The Civil War, Race Relations, and the Battle of Poison Spring. Little Rock: August House, 2002.

Dillard, Tom W. “‘An Arduous Task to Perform’: Organizing the Territorial Arkansas Militia.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 41 (Summer 1982): 174–190.

Dunivan, Major James. “A Symbiotic Alliance: Arkansas State College and the United States Army, 1935–1950.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 37 (April 2006): 14–29.

Findley, Randy. “Black Arkansans and World War One.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 49 (Autumn 1990): 249–277.

Goldstein, Donald M., and Katherine V. Dillon. The Williwaw War: The Arkansas National Guard in the Aleutians in World War II. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992.

MacArthur Museum of Arkansas Military History. Little Rock, Arkansas. https://www.littlerock.gov/for-residents/parks-and-recreation/macarthur-museum-of-arkansas-military-history/ (accessed June 30, 2023).

Maxwell, William E., Jr. Arkansas and World War II, 1939–1992: A Bibliography. Conway: University of Central Arkansas Archives, 1992.

Morgan, James L. Arkansas Volunteers of 1836–1837: History and Roster of the First and Second Regiments of Arkansas Mounted Gunmen, 1836–1837, and a Roster of Captain Jesse Bean’s Company of Mounted Rangers, United States Army, 1832–1833. Newport, AR: Logan Books, 1984.

Polston, Michel D., and Guy Lancaster, eds. To Can the Kaiser: Arkansas and the Great War. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2015.

Wolfe, Susan S. “Arkansas and the Spanish-American War.” Ozark Historical Review 2 (Spring 1973): 27–47.

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.