calsfoundation@cals.org

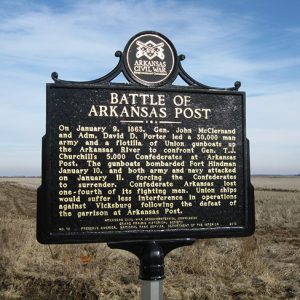

Battle of Arkansas Post

aka: Battle of Fort Hindman

aka: Battle of Post of Arkansas

| Location: | Arkansas County |

| Campaign: | Operations against Vicksburg (1862–1863) |

| Dates: | January 9–11, 1863 |

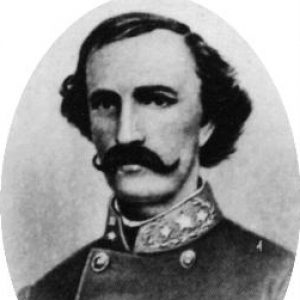

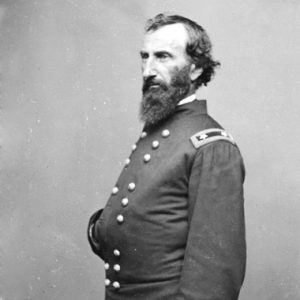

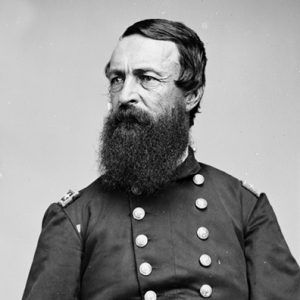

| Principal Commanders: | Rear Admiral David D. Porter and Major General John A. McClernand (US); Brigadier General Thomas J. Churchill (CS) |

| Forces Engaged: | Army of the Mississippi (US); Fort Hindman Garrison (CS) |

| Estimated Casualties: | 1,061 (US); 4,931 (CS) |

| Result: | Union victory |

The Battle of Arkansas Post, also known as the Battle of Fort Hindman, was a Civil War battle fought January 9–11, 1863, as Union troops under Major General John A. McClernand sought to stop Confederate harassment of Union shipping on the Arkansas River and possibly to mount an offensive against the Arkansas capital at Little Rock (Pulaski County).

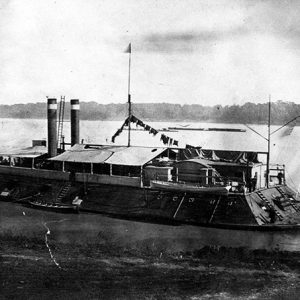

In the fall of 1862, Confederate officials ordered construction of fortifications on the Arkansas River. They selected high ground at a horseshoe bend in the river near the territorial-era village of Arkansas Post (Arkansas County) and constructed a large, square, heavily armed fortification. It was called Post of Arkansas by Confederates and Fort Hindman by the Union side. Brigadier General Thomas J. Churchill assumed command of the Post of Arkansas in December. In late December, Rebel troops captured the steamer the Blue Wing on the Mississippi River and sent it and its cargo of armaments to Churchill’s garrison at Arkansas Post.

Meanwhile, Major General John A. McClernand, an Illinois politician turned soldier, assumed command of a Union expeditionary force under Major General William T. Sherman, which had just suffered a repulse at Chickasaw Bluffs, Mississippi. McClernand, having heard of the capture of the Blue Wing, determined to use these troops and a flotilla of Union warships under Rear Admiral David D. Porter to attack Fort Hindman to protect the shipping and lines of communications of the Union army.

Despite the Union forces starting their trip on the Arkansas River by way of the White River Cutoff to avoid discovery by the Confederates, the Rebels were aware of the Union flotilla by the afternoon of January 9, 1863. Churchill ordered troops to a line of rifle pits about two miles north of Fort Hindman to hinder the Union advance. McClernand landed troops at Nortrebe’s Plantation on the north bank of the river about three miles south of the Post of Arkansas and other Union troops on the south side of the Arkansas River.

Thousands of Union troops had disembarked at Nortrebe’s Plantation by 11:00 a.m. on January 10 and begun advancing toward Fort Hindman. Churchill ordered his forward units to fall back to the Post of Arkansas at 2:00 p.m. The Confederate position was anchored by the fort on the banks of the Arkansas River. The position was supported by a line of rifle pits west of Fort Hindman that ended near the Post Bayou, which helped prevent a flanking movement against the Confederate left. Most of the Texas and Arkansas troops under Churchill’s command occupied the rifle pits as the Union troops reached their assault positions at about 5:30 p.m. Union gunboats led by the ironclads the Baron DeKalb, the Louisville, and the Cincinnati then moved against Fort Hindman, hammering the fort’s big guns and killing most of the Confederate artillery’s horses in and around the fort. By the time the naval bombardment was complete, it was too dark for the Union army to attack. Union troops spent the night listening to the Confederates chopping down trees to strengthen their defensive positions.

McClernand and his commanders spent the morning of January 11 arranging the 32,000 soldiers of the Army of the Mississippi for an assault against the strengthened bulwarks shielding the 4,900-man garrison of the Post of Arkansas. At 1:00 p.m., Porter again advanced the Union gunboats against Fort Hindman. He was aided by Union artillery that had been landed on the south side of the river and moved to where it could sweep the fort with artillery fire from across the Arkansas River. By 4:00 p.m., the guns of Fort Hindman were silenced.

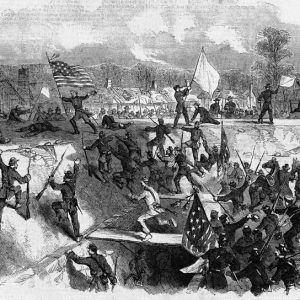

The Union infantry, meanwhile, had moved up against the Confederate lines. Troops on the Union right were fiercely engaged with the Arkansas and Texas troops defending the rifle pits. Other Union troops in the army’s center advanced against the Texans immediately west of the fort and engaged in a firefight that caused more than one-third of the Union’s losses. At about 4:30 p.m., as McClernand prepared to order a final, massive assault on the defenders of the Post of Arkansas, white flags appeared along the Confederate lines. Though Churchill denied issuing orders to give up and many of the Texans were fiercely resistant to capitulation, the garrison of Fort Hindman surrendered to McClernand’s army. Federal casualties were reported as 134 killed, 898 wounded, and 29 missing; incomplete Confederate reports showed 60 killed and 80 wounded, with 4,791 of the garrison captured.

The rebel prisoners were loaded onto transports and sent up the Mississippi River to prison camps on January 12. McClernand’s troops razed Fort Hindman and gathered the spoils of the Confederate garrison, including many of the armaments that had been captured on the Blue Wing. McClernand ordered a sortie up the Arkansas River to South Bend, Arkansas, to destroy stores of corn accessible to Confederates. On January 14, he sent a memorandum to Sherman and Porter stating that he planned to move up the river against Little Rock (Pulaski County) and other Rebel concentrations in central Arkansas. General Ulysses S. Grant, however, countermanded the plan and ordered the Army of the Mississippi to rejoin the main Union offensive against Vicksburg, Mississippi.

The defeat at Arkansas Post cost Confederate Arkansas fully one-fourth of its armed forces in the largest surrender of Rebel troops west of the Mississippi River prior to the final capitulation of the Confederates in 1865. While the victory there did not have a major impact on the Union’s drive to take Vicksburg, it did ease the movement of Union shipping on the Mississippi and raise the morale of the Yankee troops after their rough handling at Chickasaw Bluffs.

For additional information:

Bearss, Edwin C. “The Battle of the Post of Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 18 (Autumn 1959): 237–279.

Christ, Mark K. Civil War Arkansas, 1863: The Battle for a State. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010.

———. “‘Them dam’d gunboats’: A Union Soldier’s Letters from the Arkansas Post Expedition.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 66 (Winter 2007): 452–467.

Kiper, Richard L. “John Alexander McClernand and the Arkansas Post Campaign.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 56 (Spring 1997): 56–79.

Surovic, Arthur F. “Union Assault on Arkansas Post.” Military History 12 (March 1996): 34–40.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series 1, Vol. 17. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1890–1901, pp. 698–796.

Mark K. Christ

Arkansas Historic Preservation Program

My ancestors, John and Joel Simmons (father and son), fought at Arkansas Post attached to the 25th Texas Dismounted Cavalry. They’d be captured and prisoner-exchanged in May 1863. They would continue to fight with the army of the Tennessee until Nashville where Joel would be wounded on Shy’s Hill and have his right arm amputated in a Union field hospital.

My great-great grandfather, George Mills, Private, 15th Texas Cavalry, was captured by Union forces at Arkansas Post. He was imprisoned at Camp Douglas along with his brother, who passed there, prompting George to sign an Oath of Allegiance to the Union. He was listed as AWOL for the rest of the war in Confederate records.

My great-grandfather, Joseph H. Landrum of the 10th Texas Infantry, was captured at Arkansas Post and sent to Camp Douglas. Was part of a prisoner exchange in April 1863. Went on to fight battles in Atlanta, Jonesboro, Chickamauga, Franklin, and Nashville, Tennessee.

My great-great-grandfather was captured at Arkansas Post and taken to Camp Butler, where he died of either smallpox or cholera. He is buried at Camp Butler National Cemetery. He was with the 24th Texas Cavalry Co. F.

Andrew Sutton was my ancestor and one of the sixty men killed. He was from Bell County, Texas. Frank Chaulk (another member of the 6th Texas) wrote a letter describing Sutton’s death. Both legs were blown off whereby they tried to stop the bleeding. They gave him muddy water from the rifle pit. Supposedly his last words were tell my father I died a good Christian boy.