calsfoundation@cals.org

Public Health

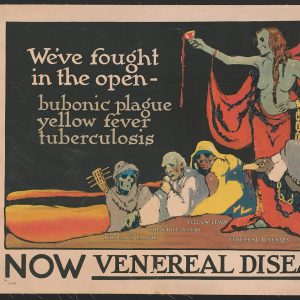

Public health is a dynamic, interdisciplinary field with the goal of improving and maintaining the health and well-being of communities through education, the promotion of healthy behaviors and lifestyles, the creation of health-related government policy, and research on disease and injury prevention. In Arkansas, the field of public health has been active since territorial days, when infectious diseases such as malaria plagued the area. In the early days, efforts to improve sanitation, prevent the spread of disease, and treat the health problems of the public in Arkansas centered on diseases—particularly malaria, hookworm, polio, yellow fever, typhoid, and tuberculosis. In modern times, public health campaigns in Arkansas have moved toward a focus on chronic health problems such as obesity and diabetes. As Arkansas is a poor and predominately rural state, protecting and promoting the health of Arkansans has proven to be particularly challenging for state and local leadership due to the additional difficulties of providing comprehensive health services to underserved rural areas. Over the years, Arkansans have suffered some of the worst health outcomes in the nation.

Public Health and Infectious Disease

In Arkansas, early public health practitioners primarily were concerned with controlling the spread of infectious disease, which eventually led to the creation of a formal public health system in Arkansas. The first city board of health in Arkansas (then Arkansas Territory) was established in Little Rock (Pulaski County) in 1832 due to concerns about the possible spread of a cholera epidemic that had infected a caravan of Native Americans who were being relocated to Indian Territory. Even though few Arkansans died in the epidemic, the yellow fever epidemic in the Mississippi River Valley in the late 1870s encouraged the state to establish the first state board of health professionals in 1879. The first permanent board of health in Arkansas was established in 1913 and focused on eradicating hookworm disease and, later, controlling the spread of malaria. This board was financed primarily by industrialist and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller. In 1916, Arkansas had become the first state to develop a compulsory school vaccination program requiring all children to have a smallpox vaccine prior to starting school.

During the Great Depression, when few people could afford private medical care, the people of Arkansas turned to public resources for their health needs. The Arkansas Department of Health worked to protect people against infectious diseases by supplying the public with vaccinations for typhoid fever, smallpox, diphtheria, and other diseases. Due to a state funding shortage, counties were required to pay individual units in each county that provided such services. In 1933, the state went bankrupt and was forced to rely on federal aid. Between 1933 and 1936, basic public health services were funded primarily through funds channeled to the state’s Emergency Relief Administration. Later, during the polio epidemic of the 1940s and 1950s, the Arkansas Department of Health incorporated public education campaigns into its efforts to promote health in the state.

These early health education campaigns focused on encouraging parents to get their children vaccinated for polio at an early age to help stop its spread and to protect their children. Immunization rates in the state remained one of the lowest in the nation. In the 1970s, Arkansas first lady Betty Bumpers spearheaded a statewide childhood immunization campaign that became a national model and led to an increase in the state’s immunization rate. She later worked with Rosalynn Carter to advocate for the first nationwide childhood immunization initiative, launched in 1977.

Arkansas’s First College of Public Health

The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) did not have a college of public health until the UAMS College of Public Health was established by the Tobacco Settlement Proceeds Act in November 2000. The act funded the new college and other initiatives to improve the health of Arkansans. The college held its first day of classes in January 2002, and the founding dean, Dr. James M. Raczynski, was hired in the spring of 2002. In 2005, the college was renamed the Fay W. Boozman College of Public Health after the director of the Arkansas Department of Health from 1998 to 2005. As of 2008, the college has more than thirty full-time faculty and more than 200 students.

The mission of the Fay W. Boozman College of Public Health is to “improve health and promote well-being of individuals, families, and communities in Arkansas through education, research and service.” Its long-term vision is “optimal health for all Arkansans.” The college offers post-baccalaureate certificates along with a variety of degree programs and has six departments: biostatistics, environmental and occupational health, epidemiology, health behavior and health education, health policy and management, and health services administration.

Public Health in Modern-day Arkansas

As common infectious diseases became less prevalent due to the successes of public health interventions such as widespread vaccination and improved sanitation, public health concerns grew to include such chronic diseases as heart disease, diabetes, and obesity. As with infectious diseases, chronic diseases disproportionately affect under-privileged populations, especially those with lower incomes or lower educational levels. The prevention and treatment of chronic diseases present new challenges to the field of public health as they involve not only the distribution of medical services and supplies but also changes in behavior and lifestyle. In Arkansas, as epidemics of chronic disease spread, the state health department and other public health organizations within the state began focusing on promoting behavior change and healthier lifestyles.

One chronic disease Arkansas has taken a lead in combating is childhood obesity. In 2003, the eighty-fourth Arkansas General Assembly passed, and Governor Mike Huckabee signed, Act 1220, a comprehensive childhood obesity prevention law. It required a ban on vending machines in schools; annual body mass index (BMI) measurements and reporting to parents; annual reports on revenue from competitive food sales in schools; and new standards for physical education, nutrition, training, and health curricula in Arkansas’s schools. Although some parts of the act were controversial at the time (such as requiring BMI reports to be recorded at schools), Arkansas made national news and attracted attention from public health experts around the country for the innovations realized by the act. In the spring of 2008, results of a four-year evaluation of the impact of Act 1220 conducted by the UAMS College of Public Health found an increase in positive attitudes of both children and parents regarding healthy eating and physical activity, as well as a decrease in the consumption of junk food, both in homes and at school, suggesting that the act has been a success.

Despite such innovative interventions, Arkansas ranks among the worst ten states in many health indicators, including hypertension, obesity, smoking rates among adults and high school students, mortality due to cancer, mortality due to stroke, and the proportion of babies with a low birth weight. In addition, Arkansas has the twelfth-largest immunization gap in the country, with 27.1 percent of Arkansan children aged nineteen to thirty-five months not fully vaccinated against common preventable diseases. Arkansas faces additional challenges due to its relatively low average income and its large rural population. People in rural areas often face poorer health outcomes than people living in urban areas. These disparities are due in part to a chronic lack of sufficient healthcare services and providers available in rural areas. These issues represent some of the most important challenges faced by the public health professionals of Arkansas as they work to improve the health and well-being of all Arkansans.

For additional information:

Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. https://achi.net/our-people-partners/our-story/ (accessed April 26, 2022).

Arkansas Department of Health. http://www.healthyarkansas.com/ (accessed April 26, 2022).

Arkansas Public Health Association. http://www.arkpublichealth.org/ (accessed April 26, 2022).

Community Health Centers of Arkansas. http://www.chc-ar.org/?msclkid=54cb90a6c58211ecb989b535705a9829 (accessed April 26, 2022).

Fay W. Boozman College of Public Health. http://www.uams.edu/coph/ (accessed April 26, 2022).

Floyd, Larry C., and Joseph H. Bates. Stalking the Great Killer: Arkansas’s Long War on Tuberculosis. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2023.

Gilien, Nancy, and Anna Gentile. “Celeste Campbell and the Introduction of Public Health Nursing to Pope County.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 68 (Spring 2009): 52–75.

Scholle, Sarah Hudson. The Pain in Prevention: A History of Public Health in Arkansas. Little Rock: Arkansas Department of Health, 1990.

Taggart, Sam. The Public’s Health: A Narrative History of Health and Disease in Arkansas. Little Rock: Arkansas Times, 2014.

Helen Cole

Brooklyn, New York

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.