calsfoundation@cals.org

Dueling

Dueling was a popular means of settling disputes among the well-bred, higher-class population on the Arkansas frontier, and though it was considered part of the code of honor for a Southern gentleman, its popularity added to Arkansas’s reputation for violence that remained until well after the Civil War.

An insult, real or imagined, likely would bring a challenge from the injured party. Duels traditionally took place at dawn to avoid interruptions, and the two parties usually met somewhere just outside the territory to get around the laws against dueling that were passed as early as the 1820s. Friends would accompany the combatants, acting as “seconds,” to see that things were carried out fairly. Seconds had to be of equal social rank as the men they served and were responsible for loading the pistols and counting paces but could not interfere in the duel. Each man usually brought along a surgeon as well. The two usually stood back to back with pistols drawn, took a set number of steps, turned, and fired. The duel ended only when one man was dead or wounded, or when one or both called a halt. Two exchanges were usually enough to prove the honor of both men, and many duels ended without injury due to the inaccuracy of the pistols used.

The smallest thing might bring on a challenge to a duel. William Allen became fascinated with a sword-cane belonging to Robert Oden. He refused to return it to its owner, playfully forcing Oden to chase him to get it back. A challenge followed, and on March 10, 1820, Allen was killed. This was Arkansas’s first recorded duel.

A challenge could be sparked by a casual slight to a lady, an insinuating remark, or a joke or prank taken wrong. Calling a man a liar was considered a direct challenge. But the things most responsible for duels in Arkansas were politics and the newspapers.

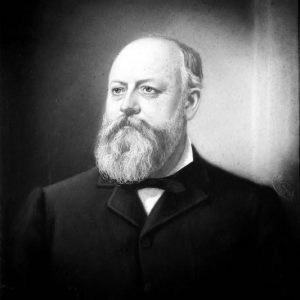

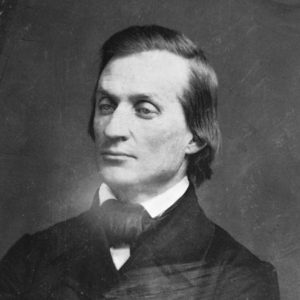

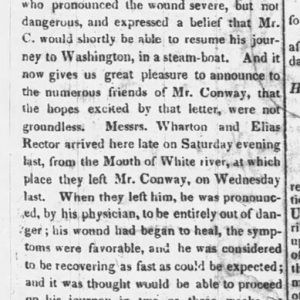

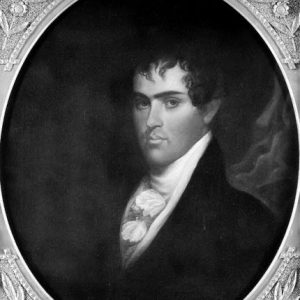

The most famous and perhaps the most tragic duel in Arkansas was in 1827 between Robert Crittenden, territorial secretary and acting governor, and Henry Conway, who was running for reelection to Congress against Oden. Tempers flared early in the election. Letters published in the Arkansas Gazette fanned the flames, and the feud continued even after Conway’s overwhelming victory. When Conway called Crittenden a liar in a published letter, Crittenden sent Conway a challenge. The two met on October 29, just across the Mississippi River from Montgomery’s Point at the confluence of the White and Mississippi rivers. Conway fired first but only grazed Crittenden’s coat. Crittenden’s first shot struck Conway, and he died eleven days later. Many duels and fistfights centered on the Conway-Oden election and its aftermath.

In 1843, Benjamin Borden, editor of the Gazette, and Solon Borland, editor of the Arkansas Banner, began a political argument in their respective papers that escalated into personal attacks. When Borden wrote an editorial accusing Borland of being a coward, Borland severely beat him. Afterward, Borden challenged Borland to a duel. They met in Indian Territory west of Fort Smith (Sebastian County). At the first signal, Borden’s gun went off by accident, and the ball went into the ground. Borland took careful aim and shot Borden clean through from the right side to the left. Borden lived, and after their duel, the two men became good friends.

Some duels did end happily. A joke might bring laughter between the duelists. Friends might intervene and work out an honorable solution. A slight wound to one or both might satisfy the challenger. In 1847, Albert Pike and John Roane exchanged shots twice, were persuaded by their surgeons to call a halt to the contest, and then caroused together in Fort Smith.

Two West Point graduates and Confederate generals fought a duel at the height of the Little Rock Campaign. Brigadier General John Sappington Marmaduke was unsatisfied with the behavior of Brigadier General Lucius Marshall (Marsh) Walker in the Battle of Helena, the August 25, 1863, Skirmish at Brownsville and the subsequent Action at Bayou Meto and asked to be removed from Walker’s command. This led to a letter exchange culminating in the two officers’ staffs arranging a duel between them, which took place on September 6, 1863. Walker was fatally wounded in the exchange of gunfire. Little Rock (Pulaski County) fell four days later.

Some men simply refused to accept a challenge and did so in such a way that their courage was not questioned. William Woodruff, Arkansas Gazette founder and editor, came out publicly against dueling as early as 1820, swearing to fight his battles with words or the law. A married man could honorably refuse to fight a single man, or a man could refuse because of religious beliefs. But most men answered the challenge, and many died. In spite of the often-tragic outcome and the laws against it, the tradition of the code duello remained the gentleman’s means of defending his honor until well after the Civil War.

Shots exchanged by John D. Adams and State Land Commissioner J. N. Smithee in Little Rock in 1878 are considered by some as the last duel in Arkansas. Dueling ended in the state due mainly to the disappearance of the elite class following the Civil War and to the passing of Arkansas’s frontier reputation.

For additional information:

Arrington, Alfred W. Duelists and Duelling in the South-West. New York: W. H. Graham, 1847.

Huff, Leo E. “The Last Duel in Arkansas: The Marmaduke-Walker Duel.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 23 (Spring 1964): 36–49.

Ross, Margaret. Arkansas Gazette: The Early Years 1819–1866. Little Rock: Arkansas Gazette Foundation, 1969.

Sherwood, Diana. “The Code Duello in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 6 (Summer 1947): 186–197.

White, Lonnie J. “The Election of 1827 and the Conway-Crittenden Duel.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 19 (Winter 1960): 293–313.

———. “The Pope-Noland Duel of 1831: An Original Letter of C. F. M. Noland to His Father.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 22 (Summer 1963):119–123.

Paula Harmon Barnett

McCrory, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.