calsfoundation@cals.org

Little Rock Campaign

aka: Arkansas Expedition

| Location: | East and central Arkansas |

| Date(s): | Mid-July to September 11, 1863 |

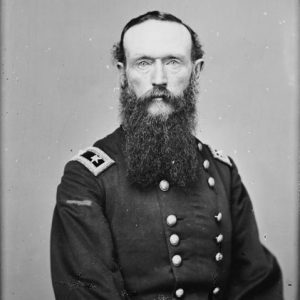

| Principal Commanders: | Major General Frederick Steele (US); Major General Sterling Price (CS) |

| Forces Engaged: | First (Cavalry) Division, Second (Infantry) Division (US); Marmaduke’s Division, Walker’s Division, Price’s Division (CS). |

| Estimated Casualties: | 137 (US); 64 (CS) (based on incomplete returns) |

| Result: | Union victory |

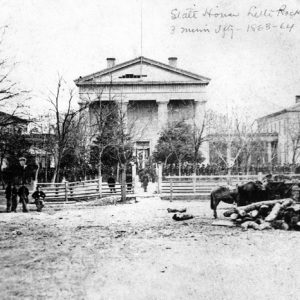

The Little Rock Campaign was a Civil War campaign in which the Union army under Major General Frederick Steele maneuvered Confederate troops under Major General Sterling Price out of the Arkansas capital, thus returning Little Rock (Pulaski County) to Federal control in 1863 and giving the Union effective control of the strategically important Arkansas River Valley.

Conditions were right for a Federal campaign to capture Little Rock and add it to the list of Union-controlled capitals of states that had seceded. The July 4, 1863, Battle of Helena had cost Confederate attackers heavy casualties and crippled their morale. The fall of Vicksburg, Mississippi, on the same day made thousands of Union soldiers available for duty on other fronts.

Authorities in Missouri were convinced in mid-July that Price, far from being crippled at Helena (Phillips County), was actually planning an invasion of Missouri with 19,000 Confederate troops. Union forces swiftly responded to the implied threat, with Brigadier General John Wynn Davidson leading a force of 6,000 Union cavalrymen out of Pilot Knob, Missouri, to head down Crowley’s Ridge. The cavalrymen crossed the St. Francis River into Arkansas at Chalk Bluff on July 19–20, 1863. Enduring short rations and persistent harassment from Confederate horsemen, the Union cavalry continued down Crowley’s Ridge to Wittsburg (Cross County) on the St. Francis River. By July 28, they were able to establish communications with and receive supplies from the Union base at Helena.

Maj. Gen. Price assumed command of the Confederate District of Arkansas on July 23 and deployed his troops, establishing a line of defense on Bayou Meto at present-day Jacksonville (Pulaski County) while ordering his cavalry to delay the approaching Union troops as long as possible. The Confederate commander also established a strong line of fortifications on high ground opposite Little Rock. While Price was officially supposed to have 31,933 troops under his command, of which 14,509 were present for duty, he later reported that his actual strength was only some 8,000 soldiers.

Davidson continued west, arriving at Clarendon (Monroe County) on August 8, where he met a small U.S. Navy flotilla. The naval vessels went up the White and Little Red rivers, capturing a pair of Confederate steamboats and skirmishing with Confederate forces in an opportunistic raid that was the campaign’s major river-based component.

As Union troops available after the siege of Vicksburg joined the garrison of Helena, Steele assumed command of the campaign to take Little Rock. On Aug. 10–11, some 7,000 Union infantry, cavalry, and artillery troops set out across the swamps of east Arkansas to join Davidson at Clarendon. Steele reported some 1,000 men sick in malarial Clarendon and turned his cavalry toward Little Rock while moving his infantry toward supposedly healthier ground at DeValls Bluff (Prairie County) on the White River by August 23. The majority of the fighting in the campaign by both sides would be by cavalry troops.

The first substantial opposition faced by the approaching Union cavalry occurred near Brownsville, north of present-day Lonoke (Lonoke County), on August 25. After a running battle with light casualties, the Union troops held the field while Brigadier General John Sappington Marmaduke’s Rebel cavalry fell back toward Bayou Meto, having slowed the Union advance. Bayou Meto was in between Davidson and Little Rock on the Military Road, which the Federal forces were using to approach Little Rock.

On August 27, Davidson moved against the considerable Confederate fortifications on Bayou Meto at present-day Jacksonville. Brigadier General Lucius M. Walker commanded the Confederate troops, though Marmaduke had operational control of the battle for the Southern forces. Following a dramatic Union cavalry charge to try to seize Reed’s Bridge across the bayou, the day-long battle was largely one of artillery, with some infantry and cavalry activity. The day ended with the Union troops falling back toward Brownsville with seven dead and thirty-eight wounded; Confederate casualties were not reported. Despite their possession of the field, the Confederate troops were ordered by Price to fall back toward Little Rock that evening.

Steele’s cavalry scouted roads in the area for several days, seeking the best avenue to make the final assault on Little Rock. Reinforcements arrived on September 2, bringing the Union’s total strength to around 15,000 men and forty-nine cannon. Confederate general Price ordered major supply caches to be moved to Arkadelphia (Clark County), sixty-five miles from Little Rock, to avoid their capture in case of Union success. Price commanded 7,749 men, most occupying the earthworks at present-day North Little Rock (Pulaski County).

The feud between Confederate brigadier generals Walker and Marmaduke that had been simmering since the Battle of Helena was exacerbated by Marmaduke’s contention that Walker had not acted bravely at Bayou Meto. A flurry of letters led to a challenge, and on the morning of September 6, the two men met with loaded revolvers at the Lefevre plantation east of Little Rock. The duel ended with Walker fatally wounded and Marmaduke under arrest, though he was freed in time to face the final Union assault on Little Rock.

Steele decided on September 9 that his troops would cross at a horseshoe bend in the Arkansas River east of Little Rock. He sent a diversionary force to Buck’s Ford, which was east of the crossing site, to confuse harried Confederate cavalrymen who were seeking to defend a dozen fordable sites along the river. Federal engineers began building a pontoon bridge at the bend and were fired on by Confederate artillery around daylight on September 10. A massive artillery response forced the Confederate troops back, and Union cavalry and infantry secured a beachhead on the south side of the Arkansas River.

Two brigades of Union cavalrymen began a steady drive against Confederate defenders along Bayou Fourche as the Union infantry began marching west along the north bank of the Arkansas River. The Union cavalry steadily forced the stubborn Confederate troops back as Price, seeing that he had been flanked, ordered his infantry to leave the entrenchments north of the river and begin retreating toward southwest Arkansas. By 5:00 p.m., the last Confederate troops were out of town, and at 7:00 p.m., civil authorities formally surrendered the capital of Arkansas. A desultory and ineffective pursuit of the fugitive Confederates on September 11 ended the Little Rock Campaign.

The Little Rock Campaign of 1863 was significant for several reasons. It effectively restricted Confederate Arkansas to the southern half of the state, ending plans to use the state as a staging ground for efforts against Missouri. Politically, it placed Arkansas’s capital under Union control, making it the fourth hostile capital to come under federal control following the captures of Nashville, Tennessee; Baton Rouge, Louisiana; and Jackson, Mississippi. The fall of Little Rock had a direct effect on President Abraham Lincoln’s decision to issue a “Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction” on December 8, 1863. The proclamation stated that, in a state that had seceded, ten percent of the 1860 voters could take a loyalty oath and then establish a Unionist government. That happened in Arkansas in January 1864, with Isaac Murphy sworn in as governor on January 4, 1864. This gentle policy of bringing Confederate states back into the fold was in effect for the next four years and reflected Lincoln’s desire to welcome rather than punish the Rebels.

For additional information:

Burford, Timothy Wayne, and Stephanie Gail McBride. The Division: Defending Little Rock, August 25th–September 10th, 1863. Jacksonville, AR: WireStorm Publishing, 1999.

Captain Benjamin Tolbert Humphrey Diaries. MacArthur Museum of Arkansas Military History, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Christ, Mark K. Civil War Arkansas, 1863: The Battle for a State. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010.

———. “Here in the Wilds of Arkansas: Interpreting the 1863 Little Rock Campaign.” MLS thesis, University of Oklahoma, 2000.

———. “‘The Sting of Being an Exile’: The Little Rock Campaign of 1863.” Pulaski County Historical Review 61 (Spring 2013): 34–47.

Huff, Leo E. “The Last Duel in Arkansas: The Marmaduke-Walker Duel.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 23 (Spring 1964): 36–49.

———. “The Union Expedition Against Little Rock.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 22 (Fall 1963): 224–237.

Mark K. Christ

Arkansas Historic Preservation Program

To read about the campaign from a CSA cavalry witness, read Thomas Jacob Barb’s diary. He was my great-grandfather. The diary is available here: http://www.rarebooks.nd.edu/digital/civil_war/diaries_journals/barb/