calsfoundation@cals.org

DeValls Bluff (Prairie County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 34º47’05″N 091º27’30″W |

| Elevation: | 191 feet |

| Area: | 1.09 square mile (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 520 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | April 4, 1866 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

186 |

380 |

605 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

924 |

885 |

672 |

686 |

830 |

654 |

622 |

738 |

702 |

783 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

619 |

520 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DeValls Bluff, in east-central Prairie County, is located on the White River and Highway 70. It is the county seat for the southern district of Prairie County. Excluding Helena (Phillips County), no other town in eastern Arkansas held such strategic importance to the Union army during the Civil War as did DeValls Bluff.

Jacob M. DeVall and his son, Chappel S., were apparently the first white settlers in the area. They first appear on Prairie County tax records in 1851. Post office department records indicate the town was named for Jacob. Chappel S. DeVall had a mercantile operation with a warehouse and home on the White River (now White River basin) in 1849. At the beginning of the Civil War, the settlement consisted of only a store, dwelling house, and boat landing.

Civil War through Reconstruction

The town was occupied by Union forces in January and August of 1863. Major General Frederick Steele occupied Little Rock (Pulaski County) on September 10. When water was low on the Arkansas River, many boats could not reach the capital city. But they could navigate up the White River to DeValls Bluff. Men and materiel could be transferred to the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad’s trains to be transported to Little Rock. For that reason, DeValls Bluff’s port area was heavily fortified for the remainder of the war and was home to many soldiers—black and white—and refugees. Although there was little interference from Confederates at DeValls Bluff, there were a few incidents of note. Union troops operated the fifty-mile section of the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad line from the port to the capital city, and there were several attempts by Rebels to disrupt service. In July 1863, a locomotive was derailed by an exploding mine, killing the crew; another train was fired upon, killing two soldiers; and on two occasions that month, small sections of track were torn out. In December of that year, a small skirmish took place outside the town.

In May 1864, Confederate forces captured three Union men and a large number of horses and mules. Rebel bushwhackers also sought to stop the movement of Union boats on the White River below town. On June 24, 1864, Confederate General Joseph Shelby sank the Queen City near Clarendon (Monroe County). In the latter part of the war, the former Confederate-turned-guerrilla, Howell A. “Doc” Rayburn, operated with his small band in Prairie and White counties, pestering Federal forces. Supposedly, on one occasion, the small-framed Rayburn, dressed as a woman, attended a dance given at army headquarters at DeValls Bluff. After dancing with some of the officers, he sneaked out, stole one of the men’s horses, and made off to join his compatriots. The Action at DeValls Bluff in August was the last of summer action in the area, but another affair took place in December.

Federal troops took down the courthouse at Clarendon and shipped the brick upriver to DeValls bluff and there used the brick to erect fireplaces and chimneys. Also, during the war, buildings were taken down at Des Arc (Prairie County) and moved downriver to DeValls Bluff.

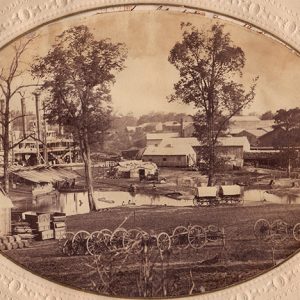

The many troops stationed at DeValls Bluff patronized stores and saloons that rapidly sprang up, many operated by Northern men such as Daniel P. Upham of New York, who came to town in the closing days of the war to open a saloon in partnership with a man named Whitty. R. H. White had a photography studio at DeValls Bluff for a time before moving to Little Rock, leaving an invaluable record of the port town during wartime.

Some of the Union soldiers and officers remained in the town following the war. William S. McCullough—a lawyer, farmer, and local Freedmen’s Bureau agent—lived there until the 1880s when he moved to Brinkley (Monroe County) and established the Brinkley Hotel. Joel M. McClintock was an early Prairie County sheriff, lawyer, abstractor, and landowner. Logan Roots (for whom Fort Roots is named) had farming operations there for a time and later became one of the state’s leading bankers. He gave the property for the town’s first Methodist church. Not long after the war, the Baptists had a church there, and African Americans had their own meeting places. Catholics erected a building around the turn of the century, aided by Protestant friends; before then, they had been served by a priest who traveled a circuit and called on families individually. Dr. William W. Hipolite, surgeon for some of the African-American troops stationed there, settled in the town and operated a drug store for many years.

Gilded Age through Early Twentieth Century

The economy and population of DeValls Bluff declined in the years following the war. The population dropped from between 1,500 and 2,000, during the war, to 250 by 1884. After the rail line between Little Rock and Memphis, Tennessee, was completed in 1871, the port began to receive fewer boats. The economy was invigorated by the opening of the Wells boat oar factory in the mid-1880s. Other wood-related industries making use of the vast stands of timber in the region followed. A shell button factory was started by Jim O’Hara of Memphis in 1896, and the industry continued well into the first half of the twentieth century.

In addition to the men previously mentioned, the Gates, Frolich, Sanders, Johnson, Robinson, Buck, Higgins, Hill, Richardson, and Thweatt families were some of the most influential in the town in the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with their business interests there and large farm holdings nearby. All were DeValls Bluff merchant families, except for the Thweatts. Joseph Gustavus Thweatt opened a law office in town in 1888, and he and his son, John Dale, were influential lawyers in DeValls Bluff for over eighty years. By the middle of the twentieth century, Hester Buck Robinson was a dominating figure in the town. A financial genius, she accumulated vast amounts of farmland in Prairie, Monroe, St. Francis, and Woodruff counties, in addition to property in DeValls Bluff, including her mercantile store.

In 1909, an African-American man named George Bailey was shot to death by a mob while housed in jail.

A courthouse for the southern district of Prairie County was built in DeValls Bluff in 1910 but razed in 1930. Using the same location and salvaged materials, workers with the Works Progress Administration (WPA) built a new courthouse in 1939. They also built a water tower in 1936.

World War II through Modern Era

The community failed to develop an industrial base after World War II. Some leaders in the town with large farming interests discouraged such development, fearing it would raise wages and take workers away from their fields. The 1940s and 1950s was a period which brought an increase in mechanized farming, requiring fewer laborers. Farm workers were leaving the state in search of better-paying jobs.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, an effort by Sam Weems of Hazen (Prairie County)—a local historian and, for a time, city projects administrator for DeValls Bluff—and several local and area citizens (including the mayor) to create a Civil War–themed state park around the Fort A, or Fort Lincoln, site became a divisive issue and did not succeed. In 2000, Arkansas State University attempted to buy forty acres of land, which included Fort Lincoln, to develop a historical/tourism site in memory of the black soldiers who served across the nation during the Civil War. This project also ended in failure.

Farming remains important to the region’s economy, especially rice farming. The King and Saul families have large minnow farm operations in the area. Hunting and fishing and boating on the White River and nearby lakes are primary forms of recreation and contributors to the area’s economy.

There was relative calm in local schools when integration commenced by stages in the mid-1960s. Over the years, the district’s school population has dropped, and consolidation with Hazen occurred at the beginning of the 2006–07 school year, though elementary grades remain at DeValls Bluff.

Notable Figures

Country singer Jim Minor was born in DeValls Bluff and is buried at Peppers Lake Cemetery south of town.

For additional information:

Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Eastern Arkansas. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing Co., 1890.

Sayger, Bill. A DeValls Bluff Remembrancer. N.p.: 1994.

———. An Eastern Arkansas Remembrancer. Parts 2, 4. N.p.: 2001, 2002.

———. A Grand Prairie Remembrancer. N.p.: 2000.

Sickel, Marilyn Hambrick. Prairie County, Arkansas: Pioneer Family Interviews by W.P.A.–Federal Writers’ Project, 1936–37. DeValls Bluff, AR: Grand Prairie Research, 1989.

Bill Sayger

Biscoe, Arkansas

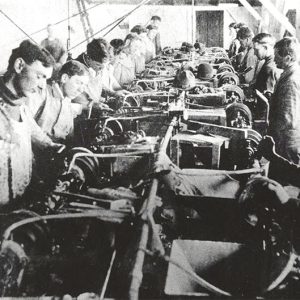

Button Factory

Button Factory  DeValls Bluff Steamboat

DeValls Bluff Steamboat  Devalls Bluff

Devalls Bluff  St. Elizabeth's Catholic Church

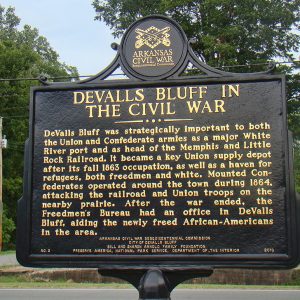

St. Elizabeth's Catholic Church  DeValls Bluff Commemorative Sign

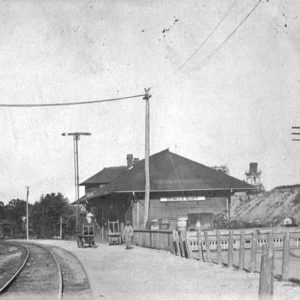

DeValls Bluff Commemorative Sign  DeValls Bluff Depot

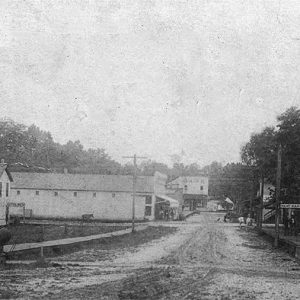

DeValls Bluff Depot  DeValls Bluff Street Scene

DeValls Bluff Street Scene  DeValls Bluff Street Scene

DeValls Bluff Street Scene  DeValls Bluff Water Tower

DeValls Bluff Water Tower  Prairie County Courthouse

Prairie County Courthouse  Prairie County Map

Prairie County Map  Steele Supply Depot

Steele Supply Depot  Thweatt House

Thweatt House  White River at DeValls Bluff

White River at DeValls Bluff  White River Bridge

White River Bridge  White River Flooded

White River Flooded

Ferdinand Gates of DuValls Bluff and his brothers owned Gates Brothers, which I believe was a dry goods store in Cooton Place, Des Arc, and Lonoke. However, Ferdinand lived in DeValls Bluff. He moved to Memphis later after his first wife died.

I loved going to my grandparents’ home in the Bluff. Hipolite drugstore was great-grandfather’s, Gennie McDuff, Carl McDuff grandparents. My family came to the Bluff in the Civil War, Wallace Hipolite U.S. cavalry surgeon. Loved the Bluff.