calsfoundation@cals.org

Fort Lincoln

aka: DeValls Bluff Fortifications

Fort Lincoln was an earthen fortification constructed in 1864 as part of the extensive network of earthworks Union forces built to protect the sprawling Federal base at DeValls Bluff (Prairie County) during the Civil War.

Confederate forces had used DeValls Bluff at various points early in the war because of its status as the eastern terminus of the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad, which ran from the White River to the north side of the Arkansas River opposite Little Rock (Pulaski County). The site had few improvements, though, and what buildings were there were destroyed by Union raiders in January 1863.

Major General Frederick Steele established a base at DeValls Bluff in August 1863 during his advance on Little Rock, recognizing the value of the railroad as a means of supplying the capital. Steamboats brought supplies up the swift-flowing White River to the river port. Steele wrote that, with gunboats securing the river side of the base, “an intrenchment can be thrown up in rear that will make the place tolerably secure against any force that will be likely to annoy us while we are pushing the enemy to the front.” Steele ordered rolling stock for the railroad to be delivered from Memphis, Tennessee, and continued his move toward Little Rock, which Confederate forces abandoned on September 10, 1863.

A major supply station was soon established at DeValls Bluff, and the railroad became the focus of attacks by Confederate troops and irregulars. The Federals tried to protect the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad with cavalry patrols, but DeValls Bluff itself would not receive substantial fortifications until after Confederate general Joseph O. Shelby’s troops destroyed Union hay-gathering operations in the August 24, 1864, Action at Ashley’s Station. In this confrontation, five prairie fortifications were destroyed, the majority of the Fifty-fourth Illinois Infantry Regiment was captured, and miles of railroad track were destroyed just west of the base.

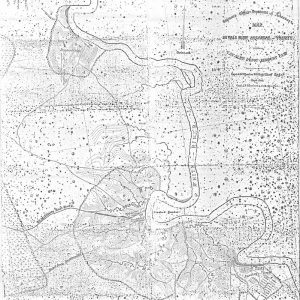

Captain Junius B. Wheeler, Steele’s chief engineer, drew up plans for a fairly elaborate system of earthworks anchored by three redoubts commanding a bend in the White River, at which the main Union riverport was located. Wheeler recommended a garrison of 1,000 infantrymen, twelve cannon, and 500 cavalry to protect the base. Wheeler wrote that “Devall’s Bluff is badly located for defense in many respects. I have laid out, and there are now in process of construction, three inclosed redoubts, requiring for a firm defense the numbers before given.”

On October 4, 1864, Brigadier General Christopher C. Andrews reported that he “had 100 men at work on the earth-works, which are progressing as fast as my means allow.” A month later, he reported in a letter to President Abraham Lincoln that 500 troops were laboring on the forts, “all of which I hope to have finished in a few days. One of my regiments is the Fifty-seventh U.S. Infantry (colored) and [it] is at work on the last and heaviest earth-work. I told them the other day I thought if they made a good fort of it, we should call it Fort Lincoln, which greatly pleased the men and made them shovel faster.” Bad weather complicated the construction, leading Andrews to report on November 27 that “it looks very bad to see heavy works laid out and left unfinished.”

No other reports on the fortifications at DeValls Bluff are known, and the base did not suffer a concentrated attack by Confederate forces before the war ended in 1865. Of the three redoubts planned, only one survives in the twenty-first century: the southernmost fort labeled Fort A on Wheeler’s map still stands on private property. This earthwork may be the one that Andrews optimistically christened Fort Lincoln.

For additional information:

Roberts, Bobby, and Carl Moneyhon. Portraits of Conflict: A Photographic History of Arkansas in the Civil War. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1987.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I, Vol. 41, part 3, p. 607, part 4, pp. 415, 666–667, 699. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1893.

Mark K. Christ

Little Rock, Arkansas

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Military

Military ACWSC Logo

ACWSC Logo  DeValls Bluff Fortifications

DeValls Bluff Fortifications

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.