calsfoundation@cals.org

Crittenden County Expulsion of 1888

In July 1888, a group of influential white citizens in Crittenden County expelled a number of prominent African-American citizens and county officials. Apparently weary of the fusion governments that had prevailed there for years, as well as fearful of the outcome of the upcoming September and November elections, they hoped their actions would intimidate Black voters and ensure a victory for white Democrats.

Following the Civil War, land agents began to recruit Black laborers from around the South to work in the cotton fields. By 1870, the Black population in Crittenden County had reached sixty-seven percent, the majority for the first time. The emergence of a Black middle class tied to the Republican Party threatened the hegemony of the white planter class, leading to increasing racial animosity in the immediate post-Reconstruction period. After 1874, when the Democratic Party returned to power in Arkansas, Crittenden County, like several other Black majority counties in the state, chose to run its elections under a “fusion agreement.” Under such an agreement, political parties met prior to the election and allotted certain offices to Democrats and others to Republicans, with concurrence that the candidates put up by each party would run unopposed. In 1874, Benjamin Westmoreland was elected county treasurer, but he was killed by a white man before his term expired. In 1878, voter fraud and destruction of ballots resulted in the election of an all-white slate of Democratic officials. By 1880, the county’s population was eighty percent African American.

Political tensions were also increasing in the county. Economic hardship had led farmers to form third-party alliances like the Union Labor Party. White Democrats, already tiring of the fusion agreements, felt that any Union Labor Party victory would further undermine their power. Early in the summer of 1888, a group of approximately twenty-five of Crittenden County’s white citizens met in Memphis, Tennessee, to formulate a plan to rid the county of its Black officials. Among those in attendance were Judge S. A. Martin, Sheriff W. F. Werner, Colonel J. F. Smith, Dr. W. M. Bingham, and L. P. Berry. They reached no conclusion at this first meeting but met again a few days later and came up with a plan.

According to the New York Times, during the first week of July “a half dozen prominent planters” were reportedly “notified through their colored servants that their lives were in danger, as the negroes were determined to drive the white people out of the county or kill them.” In response, the county’s whites armed themselves with seventy-five (some sources say fifty) Winchester rifles procured in Memphis. Meanwhile, the county judge D. W. Lewis and the county clerk David Ferguson, both Black, had been indicted for public drunkenness, and the trial was to be held on July 12. Lewis was a former schoolteacher, superintendent of schools, county clerk, and member of the Arkansas General Assembly. Under Arkansas law, any accusation of drunkenness resulted in the accused official’s removal from office (although in this case, neither Lewis nor Ferguson was removed). The Times reported that the present grand jury, made up of white men, also planned to investigate several other African Americans. The trial, however, never took place because of the following events.

On the morning of July 12, several prominent white citizens—among them Martin, Werner, Smith, Bingham, and Berry, all of whom had attended the Memphis meeting—reported that they had received anonymous letters asking them to leave the county. A group of armed whites came to the courthouse and ordered Lewis, Ferguson, and Ferguson’s deputy, J. L. Flemming, to leave the building. In addition to being deputy clerk, Flemming was the editor of the Marion Headlight, a Black Republican newspaper. The three were told about the letters and asked to leave the county. Ferguson replied that he knew nothing about the letters and refused to leave. Along with several others, he asked that the circuit court investigate the accusations. According to the Contested Election Case of Featherston[e] v. Cate, a person in the infuriated crowd declared, “God damn you, you’ve got to leave this county, this is a white man’s government and we are tired of negro dominance; we have been planning this for the past two years, and no more Negroes or Republicans shall hold office in this county.”

A group of seventy-five to 100 armed whites also rounded up a number of the county’s other prominent African Americans. Among them were the county assessor J. R. Rooks, state representative S. S. Odom, and O. W. Mitchum. Eventually, eleven prominent African Americans were forced at gunpoint to go to Memphis. After everyone had been expelled, white citizens searched homes, businesses, and lodge halls for weapons and ammunition. None were found.

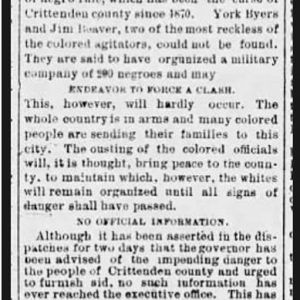

This first action was followed by a second wave of expulsions, focusing more on prominent citizens and Black Republicans who owned property. Among these were York Byers, who owned 200 acres of land, had run unsuccessfully for sheriff, and was an Agricultural Wheel member. Also expelled was Wheel member Jim Devers. According to the New York Times, Byers commanded a militia of over more than 200 men, and Devers was his lieutenant. They were believed to be organizing the Black citizens of the county. Black men began disappearing from the fields and going into hiding.

By July 15, the Times was reporting that the “race war” had ended. Although things were quieter, many Little Rock (Pulaski County) Democrats were condemning the expulsion of the African Americans, claiming that “the law was fully competent to deal with the trouble and that the resort to mob violence was both unnecessary and unwise.” According to the report, there would be an investigation, following which “offenders against the law, white or Black, [would] be punished.”

The situation was far from over, however. By July 16, Ferguson, Rooks, and O. W. Mitchum were in Little Rock to present Governor Simon Hughes with a petition, signed by seventeen other exiles, asking him for protection so they could return to the county. The governor took no action, but while the three were there, they were interviewed by a reporter for the Arkansas Gazette. In response, a white delegation went to Little Rock to present its side to the governor and the newspaper. Governor Hughes did not provide the desired protection but instead filled all vacant county offices with white Democrats.

Within days, according to the New York Times, Judge J. E. Riddick had charged a grand jury “to discover and indict for conspiracy the persons who sent the threatening letters to white citizens of the county, which gave rise to the recent race troubles,” adding, “There is no such punishment as expatriation known to the laws of this country, and even if there were, its execution would not safely be intrusted [sic] either to a set of midnight conspirators or to a lot of armed and excited citizens.” By July 24, the grand jury issued indictments against the nineteen African Americans they believed had conspired to produce the anonymous letters. No indictments were handed down against white citizens who had driven African Americans from the county. According to the Times, although there had been rumors about subsequent lynchings and trouble between Blacks and whites in Marion: “The county has been quiet as a millpond since the drunken negro officials and their fellow conspirators were compelled to take ‘French leave.’”

There were continued efforts on the part of whites to disrupt the upcoming September elections. Attempts were made to interfere with the county’s Republican convention. The new Democratic county judge appointed all Democrats to be election judges. This, coupled with the fact that Democrats held all major county offices, made it possible for the Democrats to intimidate voters and effectively control the election process. Despite all this effort, however, the Union Labor Party still carried the county with fifty-four percent of the vote in the September gubernatorial election. The November elections were also marked by fraud. According to the official results, the Democratic candidate defeated Lewis Porter Featherstone in the race for the First Congressional District. Featherstone contested the results, and the U.S. House of Representatives found evidence of fraud and intimidation and awarded him the seat in February 1890.

Racial tension continued in the county. In late November, a Black man named Jim Smith was lynched for allegedly making an “insulting proposal” to the wife of a white farmer. Smith was arrested, but as he was being taken to jail, a mob of white men took him and “filled him full of bullets.” According to the New York Times, “The negroes are excited, and a number of them have left the neighborhood, fearing that the whites will carry their vengeance further.”

In the long run, the Crittenden County expulsions failed to quash African-American participation in the electoral process. Black candidates, including state representative George W. Watson, continued to be elected until statewide disenfranchisement laws were enacted in the mid-1890s.

For additional information:

“Black against White: A Conflict in Arkansas Considered Probable.” New York Times, July 12, 1888, p. 2.

“A Colored Brute Lynched.” New York Times, November 29, 1888, p. 5.

“Crittenden County Troubles.” New York Times, July 18, 1888, p. 2.

“Featherstone Seated.” Arkansas Gazette, March 6, 1890, p. 4.

Jones, Krista Michelle. “‘It was awful but it was Politics’: Crittenden County and the Demise of African American Political Participation.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2012. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/466/ (accessed August 22, 2025).

“No Trouble at Marion.” New York Times, July 25, 1888, p. 3.

“A Race War Ended.” New York Times, July 15, 1888, p. 2.

U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Contested Elections. Contested Election Case of Featherston v. Cate, from the 1st Congressional District of Arkansas (51st. Cong., 1st. sess.). Washington DC: 1889.

“A War of Races Averted: What Caused the Trouble in Arkansas.” New York Times, July 13, 1888, p. 2.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Clinton, South Carolina

And nothing has changed in 2025.