calsfoundation@cals.org

World War II Ordnance Plants

aka: Arkansas Ordnance Plant (AOP)

aka: Maumelle Ordnance Works (MOW)

aka: Southwestern Proving Ground (SPG)

aka: Ozark Ordnance Works (OOW)

aka: Shumaker Naval Ammunition Depot (NAD)

During World War II, Arkansas was home to six ordnance plants. The sites were located near Jacksonville (Pulaski County), Marche (Pulaski County), Hope (Hempstead County), El Dorado (Union County), Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), and Camden (Ouachita County). The uses for the locations included the manufacture of detonators, fuses, primers and bombs; proving grounds for testing munitions; rocket loading, testing and storage; and producing chemical agents needed in bombs and explosives. Four of the plants were government owned and contractor operated (GOCO). These plants were over seen by a military staff, but a private corporation had the contract to operate the plants. The Southwestern Proving Ground and the Pine Bluff Arsenal were government owned and operated. All the plants depended heavily on civilian workers for their main work force. The wartime industries brought needed money and jobs for Arkansas citizens and contributed greatly to the economy of Arkansas. After the war, the state never returned to heavy agricultural-based economy that had been present before World War II, developing instead a more industrialized economy.

Arkansas business and political leaders lobbied for the plants and pointed out the advantages of locating plants in Arkansas. Arkansas had unlimited supplies of natural gas and coal. Arkansas offered strategic locations away from the coastal areas of the United States where the government felt the plants were safer from foreign attack and away from large population centers but with a large available labor force.

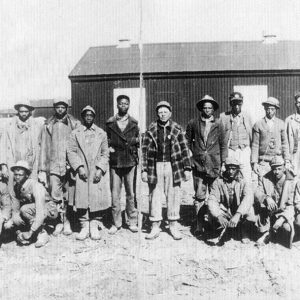

With the able bodied men needed for military service, the job of manning the defense plants fell to people that had never been in the labor force before or who had been employed in low-paying work. Handicapped people, women (many who were housewives and had never worked outside the home), young people, older adults, and African Americans were sought for employment. Boys and girls as young as fourteen and fifteen were hired for work. These young people changed their papers or lied about their age, and the need for workers was so great that the employment officials did not check up on the ages. African Americans were encouraged to apply, and as segregation was still practiced in Arkansas at this time, separate areas of the employment facilities were set aside for the African Americans who came to apply for work.

The ordnance sites shared many of the same features. First, the land areas for the plants were surveyed and taken over by the United States government by condemnation proceedings. This action displaced the people living in those land areas, and the people had to move out in a short period of time. Housing shortages developed in many areas as workers from all over the state and even out of state came to work on the construction phases of the plants. Local people were given preference. Trailer camps developed, and area residents rented out about anything they had. All but one of the plants built housing for their top military personnel, and in the case of the contractor-operated plants, housing was provided for top operating officials. During the operating phase of the plants, most of the workers came from areas within about a fifty-mile radius of the sites, but workers from further away also came, and these workers especially had problems with housing. Transportation was a problem, bus and rail services were developed, and individual passenger vehicles were used to transport workers.

The plants developed into almost self-contained communities. Sewer systems and water systems were developed. Roads and railroads were built within the sites. Spur lines were built to connect to outside rail services. The plants had their own hospitals, fire departments, maintenance departments, and cafeterias, and several of the plants had recreation facilities on the grounds. All the sites were fenced, plant guards patrolled the sites, and security was very tight. Several of the plants produced their own newsletters.

Arkansas Ordnance Plant (AOP)

On June 4, 1941, the War Department notified Governor Homer Adkins and Congressman David D. Terry that a $33,000,000 fuse and detonator plant was approved for immediate construction near Jacksonville. The plant was the first national defense industry approved for the state, and at the peak of production on November 22, 1942, 14,092 workers were employed at the plant.

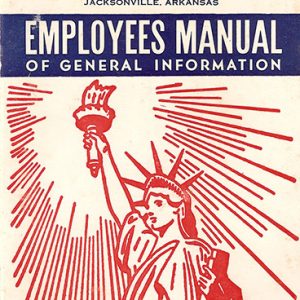

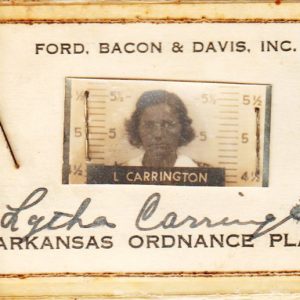

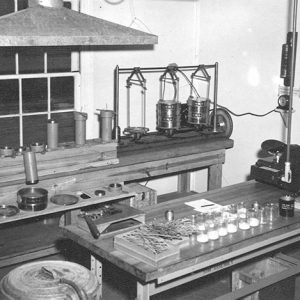

The contract to design, construct, and operate the plant, as well as train key personnel, was awarded to Ford, Bacon & Davis of New York, making this plant a GOCO plant. The plant was named the Arkansas Ordnance Plant and was one of the first plants of its kind in the nation. The facility had several assembly lines that occupied clusters of buildings where fuses, boosters, detonators, and primers were produced. The first assembly line was completed on March 4, 1942, and additional lines were all operational by June of 1942.

The majority of the production line workers were women called WOWs (women ordnance workers). In August 1943, 12,686 employees were working at the plant, and about seventy-five percent of these were female. By December 31, 1944, there were 3,085 African Americans working four lines and comprising twenty-four percent of the work force. There were fifty-five African-American supervisors.

Transportation to the AOP was provided by Inter-City Transit Company buses and Missouri Pacific Railroad shuttles, as well as private vehicles. The Sunny Side housing project, consisting of a total of 375 houses and additional duplexes, was started on July 5, 1942. The project supplied housing for 500 families. A 200-unit trailer park was built on the opposite side of town from the project, and both developments were rented to the AOP employees as they were completed. The chief architect for the Sunny Side project was Edwin B. Cromwell of Little Rock (Pulaski County). The houses were prefabricated in Memphis by E. L. Bruce Lumber Company. Young A. Maury of Memphis was in charge of construction of the houses. The completed sections were brought to the Jacksonville site, where crews could put up several houses a day. Dormitories were built on the AOP site. Staff housing was built on the site for the management and military personnel. Recreation facilities were built on the site. Housing, especially in the beginning, was never enough, and some workers lived in tents and in their vehicles.

The AOP continued in production from 1942 until August 1945 and produced 1,062,336,263 detonators and relays, 106,697,860 primers, 328,948,476 percussion elements, 175,856,066 fuses, and 5,810,315 boosters. As the war began winding down, the number of employees needed decreased, and by August 1945, the number of employees had dropped to 7,000. By the end of August 5, 600 of the employees were dropped from the payroll, and the plant was completely closed within six months.

In 1946, the AOP facilities were offered for sale. Some buildings were leased or sold to industries that located on the old plant site. Other buildings were removed from the site and taken to educational facilities around Arkansas. Some of the land was sold back to former owners, with a clause that, if the government needed the land, it would be retaken. The Little Rock Air Force Base took in part of the former AOP site in the 1950s, and some of the owners had to give up their land for a second time.

In 2002, the Little Rock Air Force Base Historical Foundation, Inc. purchased a building located on the site of the former AOP administration building. That building was converted in 2004 to the Jacksonville Museum of Military History, which includes information and artifacts on military history from the civil war to current military conflicts. One area is dedicated to the history of the AOP, and a former AOP guard house is located on museum grounds.

Maumelle Ordnance Works (MOW)

Washington’s approval for a plant to produce picric acid, used in making of explosives, came on June 6, 1941. Maumelle Ordnance Works, located near Marche, was expected to employ 800 to 1,000 people in the production phase of operations. The construction workers came from all over Arkansas, and housing shortages and transportation problems were evident here also. Buses and private vehicles provided transportation, but because the MOW was a smaller plant with fewer workers, the plant did not have as many housing or transportation problems. Cities Services Defense Corporation of New York was the primary contractor for the estimated $10,000,000 project, and this plant was another GOCO plant. No housing was built at the MOW site. Initial production of picric acid began on March 28, 1942.

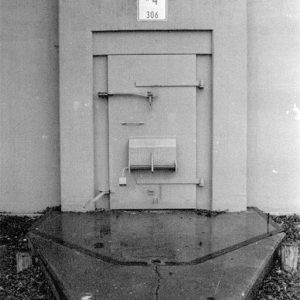

MOW remained in operation from March 1942 until August 1945 and produced 113,692,135 pounds of ammonium picrate. After the war, the plant was kept on standby status with a small military and civilian staff ready to put the plant back into production if needed. It was never reactivated, and in 1959, it was declared surplus and offered for sale. The city of North Little Rock (Pulaski County) purchased MOW and planned to build a large industrial complex on the site. The plan for the industrial complex never materialized, and in 1967, the property was sold to Arkansas entrepreneur and insurance executive, Jess P. Odom. Odom put together an idea for a “New Town,” and his vision became the town of Maumelle (Pulaski County). Bunker No. 4 from the MOW is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Southwestern Proving Ground (SPG)

On June 6, 1941, Representative Oren Harris and Senator George Lloyd Spencer notified the Hope Star that a proving ground to test ammunition would be located near Hope. The Southwestern Proving Ground cost about $15,000,000 to construct. Adjacent to the proving ground was built an airport described as being the third largest airport in the United States at completion in 1942. Located in the airport area were barracks and the headquarters of the 616th Army Air Corps Detachment. The detachment flew aircraft to test air bombs at the proving ground testing range and dropped bombs for testing in the Gulf of Mexico.

By July 19, 1941, approximately 400 families had received orders to move from the plant construction area. Cemeteries in the area were also relocated. The displaced people in this area were the hardest hit of any of the war plant sites. The majority of the displaced families were poor with few resources. The National Guard brought in tents for temporary quarters for them.

The Callahan Construction Company constructed the facility. This facility was administrated by the Army Ordnance Department and was government owned and operated. The first shots at the testing grounds were fired on January 1, 1942. The proving ground was fifteen miles long and five miles wide. Machine gun shells, anti-tank gun shells, howitzer shells, and bombs of all types were tested at the site.

The proving ground employed approximately 500 civilians. The site closed in September 1945, leaving 40,000–50,000 acres of shell-torn wilderness. The Army condemned the area as being uninhabitable and unfit for any use because of the danger of unexploded bombs and shells. The airport area, considered a safe area, was conveyed to the city of Hope for an airport.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, under its Formerly Used Defense Sites (FUDS) program, began cleanup of the SPG in 1993. Over 8,000 ordnance items were removed from the site by 2003. The Southwestern Proving Ground Airport Historic District was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on June 10, 1999. A group of citizens of Hope began working on a museum called A Sentimental Journey to Southwestern Proving Ground, to be located in the old generator building of the Airport Historic District. In 2003, 2004, and 2005, this group held balloon races to commemorate the Southwestern Proving Ground, honor former Senator Lloyd Spencer, and raise money for their museum.

Ozark Ordnance Works (OOW)

The War Department informed Representative Oren Harris on October 8, 1941, of the approval for a $23,000,000 ammonia plant to be located near El Dorado. The plant, known as the Ozark Ordnance Works, produced ammonia and ammonium nitrate, used in manufacturing explosives and in the filling of shells and bombs. The plant was built and operated by the Lion Chemical Corporation, a subsidiary of the Lion Oil Company of El Dorado. This plant was another GOCO facility.

Colonel T. H. Barton, president of both the Lion Oil Company and Lion Chemical Company, worked hard to get the plant for south Arkansas. In an interview in 1947, he recalled, “When we were negotiating for this plant, the War Department told us flatly we could not produce ammonia from natural gas. They did not know us Southerners. It took a lot of talk and argument but we finally won out.” The process to use natural gas in the production of ammonia was new, and Lion hired seventeen engineers and sent them to Canada for training. This plant was the first plant to use the new process in the United States. Production began in 1943 and continued until 1945.

A building the size of two football fields was built to house the huge gas engines that produced the electricity to power this plant. The contracted daily amount of production for this plant was set at 300 tons of ammonia to be converted to 300 tons of ammonia nitrate solution. About 700 employees were needed to staff the plant during the production phase. Housing and transportation were problems here, but to a lesser degree. The only housing built on the site was for single male employees and visiting male dignitaries.

After the end of the war, production continued under the Lion Chemical Corporation for commercial purposes. Monsanto Chemical Company merged with Lion Chemical Corporation in 1955 and operated the plant under the Monsanto name until July 29, 1983, when the plant was sold to El Dorado Chemical Company.

Pine Bluff Arsenal (PBA)

On October 21, 1941, the War Department notified Senator Hattie Caraway and Representative William F. Norrell that the Pine Bluff area had been approved for a plant for the manufacture and assembly of magnesium and thermite incendiary bombs.

The contract to design and construct the new chemical warfare arsenal was awarded to Sanderson and Porter of New York City. The initial site consisted of approximately 5,000 acres for the production area and 3,000 acres for a bomb storage site. The site was constructed so that it could be a permanent armament factory after World War II. This facility was government owned and operated.

Housing was a severe problem during the construction of the arsenal. The Farm Security Administration set up a 400-unit trailer park for the workers. Tents and temporary shacks sprung up beside the road from Pine Bluff to the PBA, and the Little Rock Bus Line ran bus services between Little Rock and the arsenal. A town, Plainview, was developed for the production workers with houses, stores, and all necessary services.

A unique solution to the housing problem during construction was the use of quarter-boats. Seven quarter-boats belonging to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in Memphis were towed up the Arkansas River from Memphis. Along with the quarter-boats were six barges containing refrigerator plants, cold storage vaults, washrooms, electric power plants, distilling plants, and supply rooms. The “floating hotel” slept up to 1,000 men.

On April 6, 1942, the newly completed administration building was opened to the public.A chemical warfare expert demonstrated an incendiary bomb for the crowd. The first shell was produced at the arsenal on July 16, 1942. By October 1944, approximately 9,000 civilians were working at the arsenal, 450 military personnel supervised operations, and PBA had been expanded to manufacture chemical munitions and smoke weapons. Women comprised ninety percent of the African American employees and fifty percent of the other workers. The area for the arsenal was expanded to 15,000 acres by the fall of 1943. The Arkansas Gazette announced on October 23, 1944, that the Arsenal had produced 727,123,196 pounds of “hell fire” since production started in 1942.

In August 1945, 2,500 employees, mostly women, were terminated. Male employees were retained for clean-up. PBA remained in operation after World War II, but production decreased. In 1953, PBA became the only U.S. site for full-scale production of biological munitions and continued in this capacity until 1969. PBA products and services were heavily used in World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and Desert Storm. PBA remains the second largest stateside storage site for the nation’s chemical stockpile. The Arkansas Democrat-Gazette announced on October 3, 2004, that the PBA was setting up furnaces to destroy 3,850 tons of outdated chemical-filled rockets, bombs and warheads. The burning of the munitions started in 2005.

Shumaker Naval Ammunition Depot (NAD)

On September 25, 1944, Senator John McClellan and Representative Oren Harris announced that a $60,000,000 Navy ordnance plant would be built near Camden. The plant was situated northeast of Camden and covered 68,417.82 acres in Calhoun and Ouachita counties. The Bureau of Naval Yards and Docks supervised the land and buildings, and National Fireworks, Inc. of Hanover, Massachusetts, contracted for operations, making this another GOCO plant. The plant was named for Captain Samuel R. Shumaker, a Navy ordnance officer, who had served thirty-three years in the Navy and was killed in the Pacific Area during World War II. The plant produced all types of rocket bombs.

By January 1945, Camden Transit Company was providing transportation from Camden and neighboring towns for construction workers. The Camden News reported that the plant was to be the principal rocket loading, assembling, and storage site for the nation.

More than 24,000 construction workers were hired to complete the plant; starting wages were $0.65 per hour. The final cost for the facility was approximately $200,000,000. It contained an eight-mile-long rocket testing range, production lines, ammunition storage areas, and everything necessary for operations. There was the “Billkitts” 260-unit housing development, a swimming pool, and other recreational facilities.

At the close of World War II, the plant went on standby basis. The contract with National Fireworks Corporation was terminated, and the Navy kept a small staff of Naval and civilian personnel to maintain the site and keep the NAD ready to resume production. In 1951, NAD began production again, and on May 23, 1951, the Gazette announced that National Fireworks Corporation was to take over production, and an expansion program of construction started.

In 1959, the Navy announced that NAD was considered surplus to its needs. International Paper Company purchased approximately 40,000 acres for forestry operations. Brown Engineering Corp. purchased a large portion of the NAD and developed Highland Industrial Park, and the housing development became the area of East Camden.

For additional information:

Arkansas Ordnance Plants Collection. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas. Finding aid online at https://arstudies.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/findingaids/id/12544/rec/2 (accessed May 3, 2023).

Basinger, Phillip G. “A History of the Jacksonville Ordnance Plant.” Pulaski County Historical Review 24 (September 1976): 47–55.

Hoganson, John James. “Maumelle Ordnance Works: From Wartime to the New Town.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2020.

Kent, Caroline. “Uncle Sam Needs Your Resources: A History of the Ozark Ordnance Works.” South Arkansas Historical Journal 5 (Fall 2005): 4–20.

Kent, Carolyn Yancey. “Last Hired: African American Hiring in North Pulaski County’s Citadel for Defense.” Pulaski County Historical Quarterly 62 (Fall 2014): 77–84.

Pine Bluff Arsenal. https://www.pba.army.mil/ (accessed May 3, 2023).

Smith, C. Calvin. War and Wartime Changes: The Transformation of Arkansas, 1940–1945. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1986.

Turner, Mary Nell. “Southwestern Proving Ground, 1941–1945.” Journal of the Hempstead County Historical Society (Spring 1986): 3–41.

Carolyn Yancey Kent

Jacksonville, Arkansas

My mother, Ruby Anderson, worked at the Jacksonville plant. In 1943 she received a reward for excellence in war production. She died in 2018 at age 102.

(2014) Is there any reason why land that was taken by the government for the Shumaker ordnance plant in Camden was not offered back to original owners when it was of no further use to the government? I was told by my mother that when the papers were signed for forfeiture, they were told by the people representing the government that it would be offered back to original owners at the same price the government paid them. She is the last living person in my family that signed the forfeiture papers in 1945. No offer to repurchase was ever made.

My mother is 86 years old, and she told me this evening that when she was 18 years old, she worked at the plant at Jacksonville, Arkansas: Ford Bacon and Davis plant. It must have been around 1944 because she said she was barely 18 (D.O.B. is 9/5/1926). Mother said she was paid 60 cents an hour to work on a very fast machine that pressed the cap on after the powder was put in. I am so proud that my mother was at a time and place in her life that she could work and help our country. Her name is Vearl Emmagene (Riggan) Myers. God Bless America and my mother! [Addition: Vearl Emmagene (Riggan) Myers passed away on June 8, 2013. Thank you for allowing me to place her memory in your article. She enjoyed reading it and was very proud.–Vicky Orr, August 2013]