calsfoundation@cals.org

Militia Wars of 1868–1869

A series of conflicts fought across the state in the aftermath of the Civil War, the Militia Wars were a response to the wave of violence that swept Arkansas after the adoption of the Constitution of 1868.

With the capture of Little Rock (Pulaski County) by Federal forces in 1863, Isaac Murphy was selected as the provisional governor of the state, taking office in March 1864. With little influence beyond the capital and other isolated Union outposts, Murphy was unable to consolidate his power before the end of the war. In 1866, almost the entire Unionist state government was defeated for reelection. However, Murphy and the secretary of state, who were serving four-year terms that expired in 1868, survived. The new legislature passed a number of measures designed to solidify their hold on the government while making it difficult, if not impossible, for Unionist citizens and freedmen to participate.

The U.S. Congress responded to these developments in Arkansas and across the South by passing the Reconstruction Acts in 1867 and 1868, by which state legislatures were required to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Tennessee was the only Southern state to do so, and the rest of the South was divided into military districts. Work began on a new state constitution, which would guarantee universal suffrage for men. Most ex-Confederates were banned from working on or voting against the new constitution, which was ratified in March 1868, despite numerous election irregularities. During the same election, former Union officer Powell Clayton was elected as governor, and Republicans swept the statewide offices. With the new constitution and passage of the Fourteenth Amendment, Arkansas was approved for readmission to the Union, which occurred on June 22, 1868.

Clayton took office on July 2, 1868, and immediately began to exercise the newly expanded powers of the governor’s office that were in the new constitution. The governor now had the power to appoint many of the officer holders at the county level, and Clayton took this opportunity to put Union veterans and other Republicans in these offices.

Frustration among the majority of the population who supported the Confederacy continued to grow in the face of this expanded Republican power. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) began to operate across the state in April 1868 in an effort to push the Republicans from office and regain Democratic control of the state government. Typical tactics used by the organization in the state included whippings and murders committed to discourage African-American enfranchisement. By late August 1868, both whites and blacks were being murdered across the state, with many of the killings taking place in southern and eastern Arkansas. A number of attacks on Freedmen’s Bureau officers took place, and some requested troops to protect themselves and the numerous ex-slaves who fled in the face of continuing violence. The majority of violence was seen in southern and eastern counties with large populations of ex-slaves, but even areas with few freedmen saw violence, such as Fulton County in extreme northern Arkansas. Firm numbers on the lives lost are not available, but ultimately the campaign of violence and intimidation would prove successful. Republicans and their allies were not the only targets. Thomas Hindman, formerly a Democratic congressman and major general in the Confederate army, was a vocal proponent for black suffrage and was assassinated in September 1868. James M. Hinds, the Republican U.S. representative for the Second District, was killed on October 22 in Monroe County.

In order to protect elected officials as well as citizens across the state, Clayton ordered the reorganization of the state militia in August. Only eligible voters were allowed to serve in these new units, based on provisions in the new state constitution that ensured that the majority of the members would be African Americans and white Unionists. Initially, Clayton refused to utilize these units against the KKK bands leading the attacks, although he allowed three companies of militia from Missouri to move into Fulton County in an effort to stop the violence in that county. These men, however, were ordered to not arrest anyone until after the next election was held in November. The troops from Missouri were led by a friend of the Freedmen’s agent from Fulton County, who was then killed in the violence, and the troops were sworn into Arkansas service once they crossed into the state.

While units were organizing across the state, Clayton worked to provide appropriate arms. After failing to receive help from the federal government or to borrow weapons from other states, he ordered 4,000 guns with the understanding that, if the legislature did not pay for the purchase, he would be held responsible for the bill. Democratic newspapers deplored the purchase and called on steamboats to refuse to carry the cargo. When the steamboat Hesper was hired, it was attacked shortly after leaving Memphis, Tennessee, on October 15, and the entire cargo was seized or destroyed by armed and masked men.

With violence continuing and assistance from the federal government not forthcoming, Clayton declared that voter registration was impossible in a number of counties across the state and that votes from these counties would not count in the upcoming election. In the November 3 election, the Republicans held the state, while Democrats claimed that the election would have swung to their side if voting had been allowed or votes not thrown out in a total of fourteen counties. Clayton responded by declaring martial law in ten counties the day after the election—Ashley, Bradley, Columbia, Craighead, Greene, Lafayette, Little River, Mississippi, Sevier, Woodruff. This was soon extended to include Conway, Crittenden, Drew, and Fulton counties. While martial law was imposed upon counties where much of the violence against freedmen occurred, other counties with few ex-slaves that experienced violence were also placed under martial law. The militia responded to the governor’s orders and moved into these counties without arms, uniforms, or any other supplies. Forced to gather food where it was available, the troops took items from the local population and issued receipts, which were not always honored by the state government.

The first troops, all white, assembled at Murfreesboro (Pike County) on November 13. That day, 100 of the men moved to Center Point (Howard County) in response to information that a cache of weapons was in the area. The local residents claimed that they were unaware that martial law had been declared. When a local merchant refused the militia permission to search his store, the men ransacked the business and looted. Former Union brigadier general Robert Catterson arrived in Murfreesboro that night to take command of the militia, which now numbered around 400, including the 100 men who moved to Center Point.

On November 14, Catterson moved his men toward Center Point, encountering the 100 militiamen tasked with searching for the weapons returning to Murfreesboro. The entire group continued to Center Point, encountering a large group of armed citizens at the edge of the settlement. Catterson pushed his men forward, and the two sides exchanged fire. Eight citizens and one militiaman were killed in the fight, and sixty civilians were captured. The militia reported finding a KKK meeting place and materials. Local citizens claimed that the KKK was not active in the area and that the militia had committed robbery and murder.

Catterson and his men, reinforced by a company of black militia, then moved into Sevier County. (Other counties that Catterson operated in include Ashley, Columbia, Lafayette, Little River, and Union.) While the militia did arrest some civilians suspected of participating in the KKK and executed one man accused of murdering two government agents and a freedman, Democrats in the area reported that discipline quickly broke down in the units, and the men participated in large-scale theft and acts of rape and murder. Both sides accused one another of depraved acts of violence against the local population.

Another group of militia consisting of three companies of African-American troops organized in Monticello (Drew County). Under the command of former Union officer Samuel Mallory, the troops were still organizing when a committee of Drew County citizens visited Governor Clayton and offered to create a bipartisan home guard to patrol the area. The locals knew of the acts of violence committed by the militia in southwestern Arkansas and wished to prevent the same thing from happening in their area. Clayton agreed, and the militia withdrew to Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) and Little Rock, nevertheless looting some houses as they moved out of Drew County. The home guard worked to end the violence in Drew County and joined with some militia members in late 1868 to convict and execute a KKK member for the murders of a deputy sheriff and a freedman.

Northeastern Arkansas was the site of some of the worst acts of violence against freedmen and white Republicans, and the militia campaign in that area responded with an equal intensity. Operations were based in Batesville (Independence County) and later Augusta (Woodruff County), with movements into Fulton, Crittenden, and St. Francis counties. When Daniel Phillips Upham, leader of the militia, received word that 200 men were assembling outside of Augusta on December 9, he ordered his 100 militia to take fifteen hostages from the local population. Using the threat of the death of these civilians and the destruction of the town, Upham kept the KKK from attacking his poorly equipped men while a delegation from the county visited Clayton in Little Rock. The governor refused to withdraw the militia until he was satisfied that the KKK had been disbanded in the area, which it was later that month.

Four companies of black militia under the command of James Watson moved to Crittenden County in late December, capturing several Klan members. The militia began to construct fortifications in the town around the jail. Local members of the KKK were joined by their comrades from the Memphis area and launched a number of attacks on the militia, who were finally reinforced by six companies of Missouri militia cavalry. The excursion was ultimately successful in driving most Klan members out of the county. One captured Klan member was tried and executed for the attempted murder of a Freedmen’s Bureau agent, and four other prisoners were killed while supposedly trying to escape.

Conway County was also the scene of large-scale violence against white Unionists from the mountainous areas in the northern part of the county and freedmen who mainly resided along the Arkansas River. Much of Lewisburg (Conway County) was burned in December during fighting, and Clayton called out the militia. Consisting of one company of freedmen and three companies of whites, the militia patrolled the county but was unable to stop another fire that burned in Lewisburg later in December. A committee of citizens visited with Clayton to implore him to end the occupation of the county by the militia, and the governor responded by replacing the men with regular Federal troops.

The martial law decrees for all of the counties involved in the militia war were lifted by early 1869. Crittenden County was the last county to have its order lifted, on March 21. The militia intervention accomplished its goal of restoring order and, if it did not completely destroy the KKK within the selected counties, it at least severely hampered the group’s ability to terrorize freedmen and Republicans.

For additional information:

Atkinson, J. H. “Clayton and Catterson Rob Columbia County.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 21 (Summer 1962): 153–157.

Blevins, Brooks. “Reconstruction in the Ozarks: Simpson Mason, William Monks, and the War That Refused to End.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 77 (Autumn 2018): 175–207.

Buxton, Virginia. “Clayton’s Militia in Sevier and Howard Counties.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 20 (Winter 1961): 344–350.

Clayton, Powell. The Aftermath of the Civil War in Arkansas. New York: Neal, 1915.

DeBlack, Thomas. With Fire and Sword, Arkansas 1861–1874. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Moneyhon, Carl. The Impact of the Civil War and Reconstruction on Arkansas: Persistence in the Midst of Ruin. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994.

Singletary, Otis. Negro Militia and Reconstruction. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1957.

Trelease, Allen. White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction. New York: Harper, 1971.

Worley, Ted, ed. “Major Josiah H. Demby’s History of Catterson’s Militia.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 16 (Summer 1957): 203–211.

David Sesser

Henderson State University

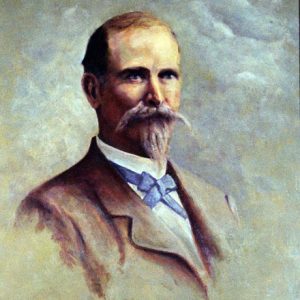

Powell Clayton

Powell Clayton

My husband’s great-grandfather, physician Marquis de Lafayette McKinzie, was one of the leading citizens who was kidnapped. The militia demanded ransom money to release the men. McKinzie’s family lacked money, so they sent a telegraph to his brother in St. Louis to ask for it. Before word came back, Mckinzie and several other hostages were tied up and thrown into the White River with rocks in their pockets. Local papers carried stories about the atrocity, and we saw one of the articles when we visited Arkansas. Nearly 150 years later the story is still passed down to each generation.