calsfoundation@cals.org

Lafayette County

| Region: | Southwest |

| County Seat: | Lewisville |

| Established: | October 15, 1827 |

| Parent County: | Hempstead |

| Population: | 6,308 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 529.47 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

748 |

2,200 |

5,220 |

8,464 |

9,139 |

5,730 |

7,700 |

10,594 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

13,741 |

15,522 |

16,934 |

16,851 |

13,203 |

11,030 |

10,018 |

10,213 |

9,643 |

8,559 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7,645 |

6,308 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

3,906 |

61.9% |

| African American |

2,057 |

32.6% |

| American Indian |

36 |

0.6% |

| Asian |

32 |

0.5% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

5 |

0.1% |

| Some Other Race |

48 |

0.8% |

| Two or More Races |

224 |

3.6% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

145 |

2.3% |

| Population Density |

11.9 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$32,397 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$25,876 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

25.9% |

|

Lafayette County has always been important to the history of Arkansas, but it was particularly so from its first four decades as a territory through the Civil War. This was partly because one of its residents, James Sevier Conway, was the state’s first governor.

European Exploration and Settlement

Before the arrival of Europeans, the area’s inhabitants were mostly of the Caddo tribe, and numerous significant archaeological sites relating to the Caddo, some dating back thousands of years, can be found within Lafayette County. Archaeological sites in the county include Battle Mound. The last Caddo village on the Great Bend of the Red River was abandoned around 1778, twenty-five years before the Louisiana Purchase added this land to the United States. The Sulphur Fork factory, established by the United States government to promote trade with various Indian tribes, operated from 1818 to 1822 on the Red River across from what would become Lafayette County. Numerous tribes, including the Caddo, traveled from above the Great Bend and from what is now Louisiana to trade at the factory. Arkansas’s territorial papers record dramatic encounters between Indians and white settlers of the area. Though the United States government closed down the factor in 1822, Indian agent George Grey continued to operate as an official government representative for some time afterward.

In the 1810s, the Caddo gave space to tribes from the eastern United States such as the Cherokee, Delaware, and Shawnee (these were not reservations created by the United States government). The 1819 Adams–Onís Treaty clarified the boundary between the United States and New Spain (including what is now Texas), and in 1820 the Arkansas Territorial Militia raided Cherokee settlers in the Red River valley west of Lewisville, forcing them away. Also in 1820, the Treaty of Doak’s Stand allocated land in southern and western Arkansas to the Choctaw, but there was no major Choctaw settlement in Arkansas. A treaty with the Caddo in 1835 moved them west to what was then northern Mexico and Indian Territory (now Texas and Oklahoma).

Identification of specific European explorers and settlers in the future Lafayette County area of the Louisiana Purchase is difficult. Nevertheless, the trading factory is evidence that a significant number of explorers—especially Spanish and French from Natchitoches and New Orleans, Louisiana—and at least some settlers came up the Red River in search of whatever treasure might be obtainable through mining, gathering, hunting, or harvesting.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

Most of the area’s adult male settlers had lived within a few miles of Andrew Jackson in central Tennessee and had served with him in the War of 1812. The war took some of them to the lower Mississippi River Valley, revealing the potential wealth of the southern river deltas. Within three years after the war, some of them were prepared to sacrifice the safety and comforts of Tennessee for the wilderness of Long Prairie across the Red River from Texas.

The displacement of thousands of farmers by the New Madrid Earthquakes also contributed to the settlement of Louisiana Purchase lands. The quakes and war prompted President James Monroe in 1815 to survey and offer lands from the purchase to veterans and displaced farmers. He chose surveyor William Rector to direct the office at St. Louis, Missouri, with responsibility for all U.S. lands west of the Mississippi River. Rector’s nephews, Henry Conway and James Sevier Conway, participated in the surveys. One result was that James Conway acquired hundreds of acres of fertile land along Red River as part of what was called Long Prairie.

Before James Conway settled on the prairie, however, a small caravan of post–War of 1812 pioneers on flatboats had arrived in 1819. In addition to their shared origin in Wilson County, Tennessee, a few miles east of Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage, and their recent service in the War of 1812, they were bonded by intermarriage. Eastern Tennessean James Conway would also marry one of them. One leader of the group was Colonel James Bradley, who in 1813 had been ordered by General Jackson to lead his troops to Natchez for the defense of the “southern country.” Thomas Dooley also served at New Orleans, and his name appears several times in Jackson’s documents at the Hermitage. George Duty served in the War of 1812 and lived a few miles from the Hermitage. William Crabtree Sr. was a resident of central Tennessee before Jackson and also served in the war.

The first years for the settlers on Long Prairie were especially difficult. Several members of the families died during the first few years, and by 1826, the year James Conway married Polly Bradley, a significant segment of the group moved 100 miles eastward. One of Polly’s uncles, Hugh Bradley, led some of the families to a portion of Union County that would become Bradley County, named for him. Stephen F. Austin lived in what would become Lafayette County for a period around 1819 and 1820, before going to Texas.

The remnant on Long Prairie persevered, however. In 1827, the year after the dispersion of Hugh and his followers, Lafayette County was formed out of Hempstead. Its original borders were the Ouachita River on the east, Louisiana on the south, Hempstead County to the north, and Texas on the west. It was named for the Marquis de Lafayette, a French ally of the United States in the Revolutionary War.

Although the initial settlers were from Tennessee, most of the county’s later settlers had more Southern roots. The extreme southeastern part of the county is even now sometimes referred to as the “Alabama” settlement.

Civil War through Reconstruction

Many of Lafayette County’s pioneers owned slaves. Old deeds in the courthouse at Lewisville mostly record only the first names of the transferees and ignore the reality that among the “property” were enslaved human beings.

The 1860 federal census recorded 4,146 white citizens in the county with 4,311 enslaved people and seven free people of color. With a majority of the population of county held in bondage, it is clear how central the institution of slavery was to the economy of the time. Wiley Cryer represented the county at the 1861 Secession Convention. According to the 1860 census, he owned at least forty-three enslaved people.

Like most areas in the South, Lafayette County was devastated by the Civil War. The direct effect on soldiers and their families was most dramatic, of course, but the economic impact also resulted in misery for almost everyone. Property and savings were lost, and genuine hunger and suffering abounded. Families who may have reported assets of $5,000 in the census of 1860, reported less than $500 in 1870. Farms went uncultivated, and what harvest was produced had little or no market. After a Confederate cavalry unit bivouacked on Long Prairie in 1862 for a while, it had to send its horses back home to southeast Texas for lack of anything to feed them.

New York native V. V. Smith moved to the county after the war ended and entered politics. After serving as county clerk, he ran for lieutenant governor on the ticket of Elisha Baxter. Later claiming that he was the legal governor, Smith’s life eventually ended at the state insane asylum.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

The most significant change during this period may have been the proliferation of family farms. The post-slavery era resulted in the dissolution of several huge plantations into smaller acreage tracts owned and farmed by families. A few former slaves were included among the new landowners, though their share of the land was relatively small, never attaining a proportionate share of the total. Land title abstracts of the era demonstrate the efforts of the large planters to retain their holdings with diminishing success. Though cotton was the main cash crop, they also produced edible grains, hay for livestock, cane for sweetening, and vegetable gardens. Diets were supplemented with wild game, fish, cattle, hogs, poultry, and other animals, along with wild berries, nuts, and fruits.

Charles M. Norwood of Lewisville ran for governor in 1888 as the candidate of the Union Labor Party. He received forty-six percent of the vote, a substantial challenge to the incumbent Democratic Party.

Another dramatic change of the era was the arrival of the railroad. East-west tracks passed just south of Old Lewisville, the county seat since 1841, and a north-south line connected it to Shreveport, Louisiana, in 1888. “New” Lewisville appeared at that junction, Bradley outgrew Walnut Hill, and Stamps, Canfield, Buckner, and other communities appeared along the rails. At the turn of the century, the Louisiana and Arkansas Railroad, initially intended to serve the interests of Bodcaw Lumber Company at Stamps, connected Hope (Hempstead County) and Shreveport, Louisiana. It would eventually be absorbed by the Kansas City Southern system. More important than the rise and decline of villages, however, were the rails for transportation of crops and timber. During much of the nineteenth century, residents tried to rely on the Red River for heavy hauling, but they were hampered by the extensive and persistent logjam called the “Great Raft.” From time to time during the second half of the century, the “Raft” was periodically declared cleared, especially after the work of the snag boat engineer Captain Henry Shreve. But it continued to be a nemesis until the river was mostly replaced as a means of transportation by the railroad.

Although the Cotton Belt rail system reduced the need for some “big ticket” retail stores in the county’s towns, better transportation increased the profitability of farming and timber harvest. It also dramatically reduced travel time to Shreveport, Texarkana (Miller County), and elsewhere. Cotton was brought from the gins to the rails, and impressive sawmills rose by the tracks at Stamps, Frostville, Canfield, Arkana, and other communities.

Residents of the county’s neighboring communities also recognized the railroad’s enhancement of the area. Several families came from Columbia County; others came from Bossier Parish, Louisiana; and farmers from southern Miller County poured onto Long Prairie, especially into the Canal and Pleasant Valley communities.

Lafayette County was the site of multiple incidences of racial violence over the decades. An unnamed enslaved man was lynched in 1859 after allegedly killing a white overseer. In 1885, George Crenshaw lost his life after allegedly killing a white man near Lewisville. The Taylor sisters were killed in 1907 after allegedly attacking a white family. Other lynchings took place in 1903, 1915, and 1926. In the 1896 Canfield Race War, African American workers were allegedly attacked by their white co-workers.

Early Twentieth Century

The first four decades of the twentieth century saw both prosperity and depression. In spite of World War I, the county was relatively prosperous until 1930. Life on the farm and in the timber business was not easy, but hardworking families survived, and many even prospered. But the economic crash on Wall Street reverberated throughout Lafayette County, not because many of its citizens were market investors, but because there were suddenly no buyers for their produce.

Banks failed, mortgagers foreclosed, properties were lost, and crop values plummeted. And yet, as devastating as it was, Lafayette County families, especially the farmers, probably suffered less than people in most areas because they were “micro-diversified,” meaning that they had gardens, chickens, field corn, orchards, milk cows, fishing holes, and nearby woodlands containing other edibles. The greater suffering resulted from the loss of land and other properties to the lenders, and the lack of cash to purchase necessities that could not be produced on the farm.

The county received funds from the Works Progress Administration for the construction of the current courthouse, with the project completed in 1942. The Art Deco building is located next to a small cemetery and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Internationally renowned author, poet, actor, and performer Maya Angelou lived in Stamps as a child in the 1930s.

World War II through the Faubus Era

Since the county had no significant war-related industries or military establishments, the most recognizable effect of World War II was the loss of county residents who served overseas. Among postwar changes in the county were the replacement of mules with tractors; reduction of plowed fields, especially in upland acres; and the consolidation and racial integration of schools. (Although desegregation eventually occurred relatively smoothly, it was passionately resisted and opposed within the county, as it was in most areas of the state.) Young people in the county, especially non-whites, began to imagine careers other than as cotton pickers or timber workers, so they migrated to Chicago, Detroit, California, and elsewhere. The population began to decline to a nineteenth-century level.

Modern Era

In 1984, James Conway and Polly Bradley Conway’s home site and cemetery at Walnut Hill were dedicated as Conway Cemetery State Park. The community has continued to celebrate its history each spring with “Governor Conway Days Festival” at Bradley, a weekend of homecoming, fun, and historic commemoration.

Recent decades have seen a reduction of family farms and a return to large plantations, and more acreage devoted to pine timber. Contracted poultry production has also grown, especially in the northern part of the county. The county is not dependent on any single large industry. Timber, general agriculture, poultry, some oil production, and other sources of revenue all contribute to the county’s economy.

In 2023, Standard Lithium of Canada purchased 118 acres of timberland in Lafayette County for a planned lithium extraction and refinement plant, scheduled to be open in 2027.

For additional information:

Hamiter, Aletha Barker. Roane Township Scrapbook. Claremont, CA: The Spittin’ Image, 1974.

Knight, Wilda, ed. Lafayette County, Arkansas: Pieces of its Past and its People. N.p.: Lafayette County Historical Society in 2002.

Lafayette Lookback. Bradley, AR: Lafayette County Historical Society (1983–).

Glynn McCalman

Mandeville, Louisiana

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

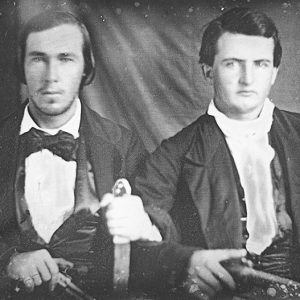

James Black & Jacob Buzzard

James Black & Jacob Buzzard  Conway Cemetery State Park

Conway Cemetery State Park  Frostville Sawmill

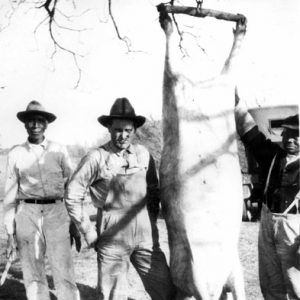

Frostville Sawmill  Hog Butchering

Hog Butchering  Lafayette County Courthouse

Lafayette County Courthouse  Lafayette County Map

Lafayette County Map  Marquis de Lafayette

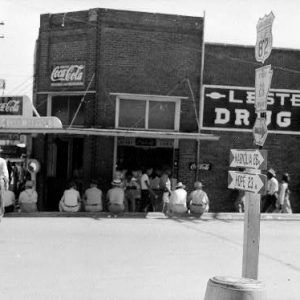

Marquis de Lafayette  Lester Drug Company

Lester Drug Company  Lewisville (Lafayette County)

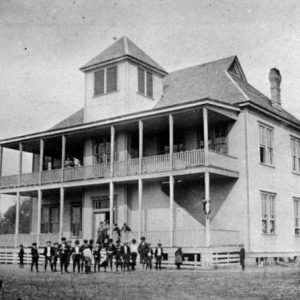

Lewisville (Lafayette County)  Stamps High School

Stamps High School  Stamps Liberty Loan Parade

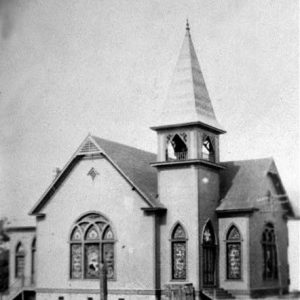

Stamps Liberty Loan Parade  Stamps Presbyterian Church

Stamps Presbyterian Church

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.