calsfoundation@cals.org

Snag Boats

As American settlers pushed westward following the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, their goals of settlement, civilization, and trade were hindered by the hazardous nature of the western rivers. The pioneers found the Mississippi River and its tributaries, such as the Arkansas and Red rivers, filled with obstacles and debris. Snag boats, tasked with the removal of sunken trees and the clearing of the rivers, were one of the first answers to the growing loss of life and property. The navigability of the rivers became a priority to settlers, who believed the future prosperity of the Lower Mississippi Valley and the western frontier, including Arkansas, was acutely tied to the safety of river trade.

As western river trade became more important to the growing nation, people began calling for large-scale river improvement. By 1824, the federal government instituted a $1,000 bounty on successful river improvement practices. Learning about the bounty, experienced boatman Henry Miller Shreve put forth his idea for a steam-powered vessel designed for the sole purpose of removing sunken trees, or snags, from the western rivers. Completed in 1829, the Heliopolis quickly steamed to one of the most dangerous stretches of the Mississippi River: Plum Point. Owing to the sharpness of the bend in the Mississippi’s course, Plum Point was constantly filled with numerous boat-wrecking snags. In two days, the Heliopolis cleared the entire stretch of river.

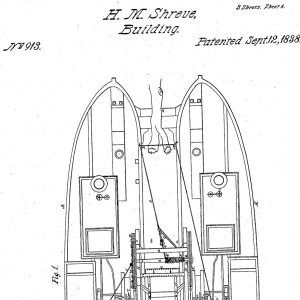

Instead of relying on manpower to lift the sometimes seventy-ton trees from the rivers, Shreve, who had been appointed Superintendent of Western River Improvements in 1827, used the pioneering mechanical power of steam to make short work of river blockages. The key component of a snag boat was a stout iron beam positioned between two heavy wooden hulls at the front of the boat. Once the crew located a snag, the boat was aimed at the tree and steamed at full power directly toward it. The beam, instead of the hull, caught the snag and caused it to either snap off cleanly below the water line or loosen from the mud, making extraction with the boat’s large iron winch possible. By putting the whole weight and momentum of the boat forward, a process that normally took a work crew several hours to accomplish, could be completed in under forty-five minutes.

After accomplishing major clearances on the Mississippi and Ohio rivers and adding a second boat to the government roster, Shreve turned his flotilla toward the muddy and temperamental Arkansas River. Arriving in July 1833, Shreve found the Arkansas at a stage much too high for snag boats to operate. When Shreve returned a month later to check on the state of the river, he was surprised to see that the Arkansas had dropped too low for work to begin. These few months of attempted work and frustration established a pattern of snag boat operation on the Arkansas for the next few decades. Shreve returned in the winter of 1834, thus avoiding the summer drought, to begin work. Finding the river at a manageable state, two vessels and teams of workmen and keelboats cleared the river and its banks as far as Little Rock (Pulaski County) before low water forced them to return to the Mississippi.

Despite the accomplishments of Shreve’s boats in 1834, the snag boats could not maintain work on the Arkansas due to other improvement projects going on in the western rivers, especially the removal of the Red River Raft (a massive logjam that clogged the lower part of the river), and a continual scarcity of funding for river improvement. Between 1834 and 1844, U.S. government snag boats entered the Arkansas only a few times. The snag boats sometimes accomplished a great deal of work but, more often, found the tumultuous river either too high or too low. By 1844, years of decreasing funding and the eventual sale of four government snag boats weakened the capacity to maintain the gains that had been achieved. Improvement of the Arkansas River slowly dwindled with the arrival of the railroad as an alternative to river transport coupled with fears over decreasing funding. Under the banner of flood control, river improvement programs would not reappear on the Arkansas until after the Civil War.

For additional information:

Adkisson, Michael Colton. “Snags, Sawyers, and Shifting Opinion: The Usage and Response to Snag Boats and Improvement on the Arkansas from 1800–1860.” MA thesis, Arkansas State University, 2017.

“Arkansas II Riverboat.” National Register of Historic Places registration form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas. Online at http://www.arkansaspreservation.com/National-Register-Listings/PDF/PU3304.nr.pdf (accessed November 5, 2018).

Brown, Carl Edgar. “Improving the way to the Land of Opportunity: Internal Improvements in Antebellum Arkansas.” PhD diss., University of Memphis, 2012. Online at https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/etd/549/ (accessed January 2, 2024).

Guested, Robert. Steamboats and the Rise of the Cotton Kingdom. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2011.

Henry M. Shreve Letters, 1827–1841. Henry Miller Shreve Collection. Louisiana State University Shreveport.

Hunter, Louis C. Steamboats on the Western Rivers: An Economic and Technological History. New York: Dover Publications, 1949.

Lloyd, James T. Lloyd’s Steamboat Directory and Disasters on the Western Waters, Containing the History of the First Application of Steam as a Motive of Power. Cincinnati, OH: James T. Lloyd and Company, 1856.

Paskoff, Paul F. Troubled Waters: Steamboat Disasters, River Improvements, and American Public Policy, 1821–1860. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 2007.

Colton Michael Adkisson

Iowa State University

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860 Transportation

Transportation Red River Raft

Red River Raft  Red River Raft

Red River Raft  Snag Boat Arkansas

Snag Boat Arkansas  Snag Boat Patent

Snag Boat Patent  Snag Boats on White River

Snag Boats on White River

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.