calsfoundation@cals.org

Cotton Industry

Cotton is a shrub known technically as gossypium. Although modest looking and usually no higher than a medium-sized man’s shoulders, its fruit helped to spin off an industrial revolution in 1700s England and foment the Civil War in the 1800s United States. The possibility of riches spun from cotton in the early days helped populate what became the state of Arkansas, with people coming by the hundreds and thousands on a trip that might last two years.

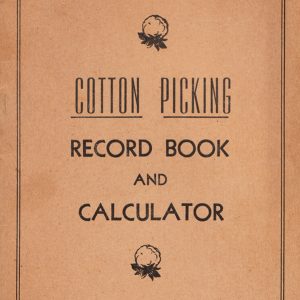

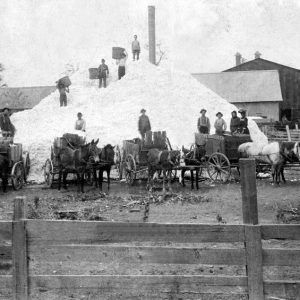

Several visitors to Arkansas in the early 1800s made note in their journals and writings of cotton being grown. The crop remained a Southern staple because it needed hot summer days and warm summer nights to bear abundant fruit. It also needed lots of labor, which in the South meant slaves, who handled every aspect of cotton production from planting in the spring to picking in the fall. After cotton planting and the achievement of a stand (a solid row of plants down each bedded row), the crop had to be blocked (elimination of all but one hardy plant per foot) and chopped to eliminate weeds and grass until a laid-by crop stood about waist high.

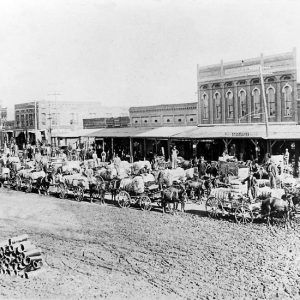

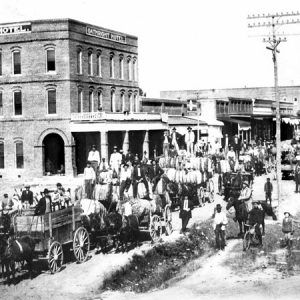

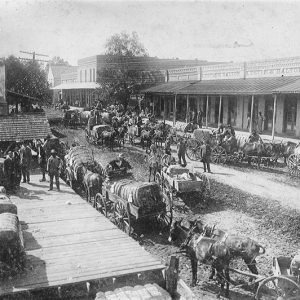

Although farmers throughout the state planted cotton, the dark earth of the Arkansas Delta proved most hospitable, encouraging large crops each year in river counties such as Mississippi County in the north and Chicot County in the south. These counties, as did others in the Delta, had easy access to river transport and thus possessed an important shipping advantage over the state’s other cotton farmers. When the Civil War ended, slavery stopped as well, and wage labor, tenant farming, or a combination of the two became the most common means of production. Typical regional farm wages in 1866 were thirteen dollars per month for men and nine dollars per month for women. Tenant shares varied but usually ranged from twenty-five percent to fifty percent. Sometimes, there was little profit to share. Cotton prices fell after the Civil War and flat-lined through the late 1890s, killing off many Delta operators. For example, the price of lint, which is cotton fiber after the seed is removed, fell to about 9.4 cents per pound by 1888–89, barely covering the cost of production.

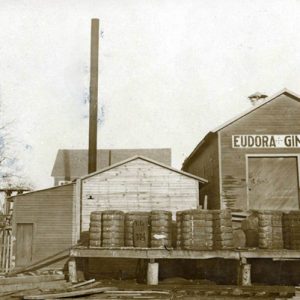

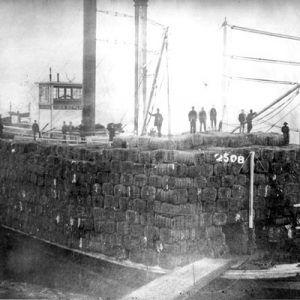

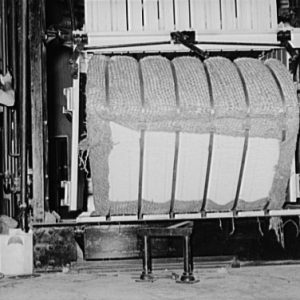

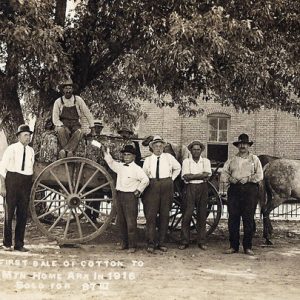

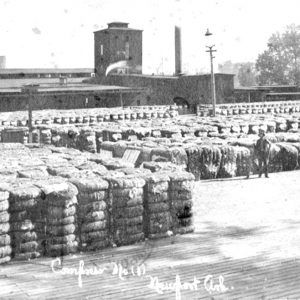

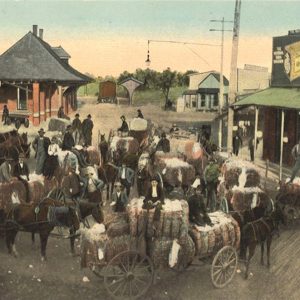

Regional cotton yields per acre varied substantially from farm to farm, usually from a low of one-half bale per acre to a high of two bales. The amount harvested depended on quality of soil, rainfall, temperature, insect infestation, and production practices. In profitable years, farmers made a bale or more per acre, with a bale consisting of about 500 pounds of lint cotton compacted into oblong units bound by webbing and ties. A common ginning arrangement gave seed to ginners as the fee for ginning, while the lint belonged to producers. After grading to determine quality of a bale’s fiber, farmers and landlords marketed their shares to cotton merchants, many of whom operated out of Memphis, Tennessee. As was the case throughout the Mississippi River Valley, Arkansas cotton farmers grew—and still do, for that matter—upland cotton. Extra long staple cotton, which ginners call Egyptian cotton, is limited to a few western states.

The planter class that cotton produced in the nineteenth-century Delta often owned thousands of acres of land. Tenants usually owned none. A typical Arkansas cotton tenant, black or white, rented forty acres from a landowner and farmed with his own mules, harrow, planter, and family for labor. Landowners got about one-fourth of the crop, with the remainder going to the tenant. At the lower end of the tenant food chain, a sharecropper lacked equipment and capital, so he farmed with landlord-supplied equipment and capital. Typically, his family received only fifty percent of the crop and had to buy supplies and personal items from plantation commissaries, sometimes at high mark-ups. Sharecroppers, particularly African Americans who lacked mobility due to race, did little more than survive. They generally had little cash after settling up with landlords and often found themselves even deeper in debt to the company store.

These profit-sharing arrangements and plantation store prices caused repeated conflicts throughout Arkansas history between tenants and landlords. Sometimes laborers and tenants organized unions and other organizations for collective bargaining with landowners. Clashes such as the Lee County cotton picker strike of 1891, the Elaine Massacre of 1919, and the formation of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union in 1934 resulted from these tensions.

Profitable cotton prices, sometimes as high as thirty cents a pound, crashed along with the stock market at the beginning of the Great Depression. There was a drought of financing as banks closed, and five-cent cotton devastated state producers. In 1933, the U.S. government devised a program to pay farmers for plowing up cotton acreage to reduce supply and so, theoretically, create higher prices. The program made plow-up payments directly to landowners and directed them to share the money with tenants. However, some owners chose to evict tenants rather than share payments, which set in motion numerous conflicts between planters and tenants.

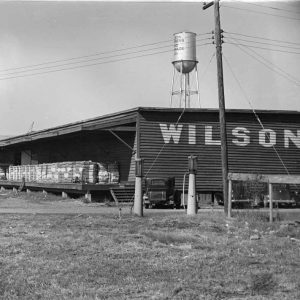

Major struggles over cotton sales proceeds and federal assistance decreased somewhat after two changes relocated Southern labor. As Northern factories ramped up in the late 1930s for a coming world war, pickers had an alternative to patches, and they headed north, moving out of shotgun houses on dusty country roads to working-class neighborhoods in cities such as St. Louis, Detroit, and Chicago. In these urban centers, hands picked up higher wages and better living conditions. A counterbalance to this loss of agricultural labor occurred in the early 1950s when mechanical cotton pickers pulled into Arkansas fields. One driver and one machine cleaned rows that previously required many hands to pick. Just as machines replaced hand labor on Arkansas farms, other crops took the place of cotton. A decline of cotton acreage in the 1930s continued as rice and soybeans captured a growing share of state farm acreage. In the early 1960s, cotton generated about thirty-three percent of Arkansas’ agricultural income. By the 1980s, that percentage decreased to twenty. Though not king anymore, cotton remains a strong cash crop for the state. In 2004, Arkansas cotton production hit a record 2.1 million bales. The state’s 2004 output contributed almost ten percent of the 23.01 million bales harvested nationwide, according to USDA records.

Cotton growing in Arkansas is big business in the twenty-first century, and it is a modern one. Seed goes into the ground when consultants determine that soil temperature is ideal. Fertilizer flows when soil tests say so. Irrigation pumps start when agronomists advise. Specialists periodically complete bug counts in fields and advise when to spray and the type and quantity of pesticides to use. Chemicals control cotton growth and the date when bolls open. Mechanical cotton-pickers glide over six rows at a time, while computers mounted in their air-conditioned cabs monitor machine operations. At turn rows, baskets dump several bales into module builders that compress them into tight units for later transport to gins.

For additional information:

Hagge, Patrick David. “The Decline and Fall of a Cotton Empire: Economic and Land-Use Change in the Lower Mississippi River ‘Delta’ South, 1930–1970.” PhD diss., Pennsylvania State University, 2013.

Holley, Donald. The Second Great Emancipation: The Mechanical Cotton Picker, Black Migration, and How They Shaped the Modern South. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Kester, Howard. Revolt among the Sharecroppers (1936). Knoxville: University of Tennessee, 1997.

Kruger, Cole T. “Arkansas’s Cotton Plantocracy: The Role of POWs in Establishing Postwar Labor Systems.” PhD diss., Kansas State University, 2023.

McNeilly, Donald P. The Old South Frontier: Cotton Plantations and the Formation of Arkansas Society, 1819–1861. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

“Oral History: Walter C. Estes Discusses Cotton Farming.” 1974. Audio online at CALS Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Arkansas Studies Research Portal: Walter C. Estes Oral History (accessed May 19, 2025).

Whayne, Jeannie M. “Cotton’s Metropolis: Memphis and Plantation Development in the Trans-Mississippi West, 1840–1920.” In Comparing Apples, Oranges, and Cotton: Environmental Histories of the Global Plantation, edited by Frank Uekötter. Frankfurt, Germany: Campus Verlag, 2014.

———. Delta Empire: Lee Wilson and the Transformation of Agriculture in the New South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2011.

———. A New Plantation South: Land, Labor and Federal Favor in the Twentieth-Century Arkansas. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996.

Van Hawkins

Arkansas State University

I have read that a strain of cotton was developed between 1890 and 1925 by Robert Henry Hallmark in the Buck Range area of southwestern Arkansas. It is said to have been planted throughout the state as a cash crop. It was simply called “Hallmark Cotton.”