calsfoundation@cals.org

Conway County

| Region: | Northwest |

| County Seat: | Morrilton |

| Established: | October 20, 1825 |

| Parent County: | Pulaski |

| Population: | 20,715 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 551.92 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

982 |

2,892 |

3,583 |

6,697 |

8,112 |

12,755 |

19,459 |

19,772 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

22,729 |

22,578 |

21,949 |

21,536 |

18,137 |

15,430 |

16,805 |

19,505 |

19,151 |

20,336 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

21,273 |

20,715 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

16,367 |

79.0% |

| African American |

2,209 |

10.7% |

| American Indian |

167 |

0.8% |

| Asian |

90 |

0.4% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

8 |

0.0% |

| Some Other Race |

433 |

2.1% |

| Two or More Races |

1,441 |

7.0% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

886 |

4.3% |

| Population Density |

37.5 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$42,802 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$25,158 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

17.6% |

|

Conway County was established by an act of the territorial legislature on October 20, 1825, from land taken from Pulaski County. It was named for Henry Wharton Conway, a member of the Arkansas Territory’s delegation to Congress. At the time, it comprised 2,500 square miles and included most of the present Conway, Faulkner, Van Buren, White, Cleburne, and Perry counties and part of Yell County. Located in the Arkansas River Valley, Conway County’s geographic structure ranges from the ridges of the Ozark foothills in the extreme northwest to the rich lowlands near the Arkansas River—a quite varied topography. The county’s native hardwood and pine forests have been a resource for the timber and recreation industries. Cotton was grown in the early days of the county, but now the dominant agriculture products are soybeans and hay, as well as poultry and livestock. In addition, Conway County’s northwest corner is the site of natural gas deposits deep underground. The Arkansas River divides the county into two unequal parts, the largest being to the north. To the south is Petit Jean Mountain (elevation 1,207 feet), the county’s highest summit.

Pre-European Exploration

Atlatl darts dating from the Paleoindian Period have been found at the Travis Moreland site, which was perhaps a camp for the butchering of animals. Other sites dating from more recent prehistoric periods have been located in Conway County, including the Alexander Site, which some archaeologists believe was a satellite community for the larger Toltec Mounds Site in Lonoke County. More than 700 pictographs are located on or near Petit Jean Mountain. Ancestors of the Quapaw Indians may have lived in the county.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

Conway County’s early settlers came by way of the Arkansas River and included trappers, traders, and fugitives. Most of the earliest settlements were along the Arkansas River and in the valley of Cadron Creek, which forms part of the county’s east boundary. The county was under French and Spanish rule before the Louisiana Purchase put it under American control, though there were no permanent French or Spanish settlements in the area. A few Americans had settled in the area before the Louisiana Purchase, such as the family of Benjamin Standlee, who lived above the mouth of Cadron Creek from 1777 to 1780.

Conway County was created by the Arkansas General Assembly on October 20, 1825. The town of Cadron, which was then located centrally in Conway County, was made a temporary county seat. In 1829, the territorial legislature moved the county seat to Harrisburg (then the house of Stephen Harris in Welbourne Township), and in 1831, the county seat was moved again after Dr. Nimrod Menifee donated a plot of land in Lewisburg for the building of a courthouse. Lewisburg remained the county seat until 1850, when it moved to Springfield because of that town’s more central location. The first post office for the county was at Peconery, an early settlement on the Arkansas River between Lewisburg and Cadron.

From 1817 to 1828, the Western Cherokee occupied a reservation in Arkansas that included a great deal of Conway County. In 1828, the Cherokee in Arkansas signed a treaty swapping this reservation for lands west of the territorial border. This coincided with the 1820s and 1830s removal of Cherokee and other Indians from the southeast United States to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) on what is known as “The Trail of Tears.” The Arkansas River was a much-used water route for Indian Removal, with Point Remove in Conway County being a stop along the route. The Via Dolorosa road was built from the east of the White River and west through Springfield to transport these Indian refugees.

The steamboat Cherokee exploded after leaving the dock at Lewisburg on December 11, 1840. The incident led to the deaths of at least twenty people.

Civil War through the Gilded Age

Dr. S. J. Stallings went to the Secession Convention held in Little Rock (Pulaski County) in March 1861 with instructions to vote against Arkansas leaving the Union, but after the firing upon Fort Sumter the following month, most Conway County citizens supported secession. Stallings owned six enslaved people at the time of the 1860 census. The county recorded 5,895 white residents in 1860 and 802 enslaved persons, showing that about twelve percent of the population was held in bondage. The county produced 3,181 bales of cotton in 1860 and almost 35,000 pounds of tobacco.

The first company in the county was organized by Robert W. Harper of Lewisburg. Other companies were subsequently raised at Lewisburg and Springfield. About 900 men from Conway County fought in the Civil War, primarily in Arkansas but also in Tennessee and Kentucky; only 200 men returned home from the war. There were no major actions fought in Conway County, although numerous minor engagements took place.

The Third Arkansas Cavalry (Union), which was partially recruited in Conway County, patrolled from a base in Lewisburg. Operations in the county included scouts to locate Confederate cavalry in June 1864, anti-guerrilla operations in August 1864, and an expedition into Johnson County in November 1864. A skirmish fought at Lewisburg on February 12, 1865, saw the end of most military operations in the county.

In 1873, the county seat was returned to Lewisburg from Springfield. In 1883, it again was taken from Lewisburg and established at Morrilton, where it remains. The current courthouse was constructed in 1929.

The Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad was completed through the county in 1872. Now called the Missouri Pacific Railroad, it includes twenty-four miles of track in Conway County. The town of Morrilton grew up around a station on this line. In 1874, the Springfield-Des Arc Bridge, which spans the north fork of Cadron Creek and connected Conway County with the newly created Faulkner County, was completed; it is now on the National Register of Historic Places.

The earliest newspaper to be published in Conway County was the Wide Awake, established in Lewisburg in January 1872. In May of that year, the Western Empire also began publication in Lewisburg. Neither paper lasted more than a few years. A number of papers have been based in Conway County since that time, but the only one surviving today is the Petit Jean Country Headlight, which was founded on April 8, 1874, by the Reverend W. C. Stout, an Episcopalian minister, as the Weekly State.

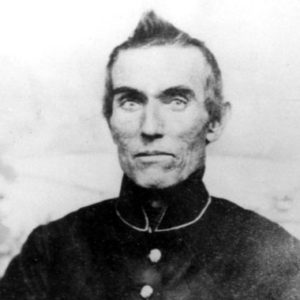

In 1889, Conway County attracted national attention when John Middleton Clayton, brother of former governor Powell Clayton, was assassinated at Plumerville (Conway County). John Clayton ran as a Republican candidate in the 1888 congressional election against Democratic incumbent Clifton Rodes Breckinridge, losing narrowly in what was one of the most fraudulent elections in Arkansas history. Clayton had the support of black Republican voters, and in Conway County, four white masked men armed with guns had stolen a ballot box at a predominately black precinct. Clayton contested the election and came to Plumerville to investigate missing votes. On January 29, 1889, he was shot through the window of his boardinghouse and died instantly. The murderer was never brought to justice, probably due in some part to a great antipathy in the county to the Republican Party and their black allies. One man who offered to turn state’s evidence in the case was murdered by his brother, though the coroner ruled the death an accident. In 1893, a man named Hickey was tried for Clayton’s murder, but though he admitted his guilt in the Conway County court, the jury deliberated for only a few minutes before returning a not guilty verdict. Clayton’s murder was only one incident of violence that was perpetrated in the county from 1886 to 1892 related to politics, with the period being known as the Plumerville Conflict of 1886–1892.

Multiple incidents of racial violence took place within the county, with at least four African American men lynched from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth centuries. At least three lynchings followed the alleged murder of law enforcement officials. The body of William Rice was discovered hanging near Plumerville on November 7, 1891. Flanigan Thornton, accused of killing a constable, was lynched on April 19, 1893. A crowd lynched John Williams on July 4, 1912, for the alleged killing of a citizen serving as a temporary deputy. The most recent lynching took place on December 9, 1922, when Less Smith was lynched for the alleged killing of a deputy.

Early Twentieth Century

Agriculture had long been a mainstay of Conway County’s economic life, with many farmers clearing land to plant cotton. In the 1930s, local farmers, like those throughout the South, were trying to plant more cotton to offset their losses due to the perpetually low price for cotton.

Many people became concerned with the number of acres left abandoned after the demise of cotton farming and sought ways to put abandoned acres back into production. Eventually, the Central Valley Soil Conservation District—comprising Conway, Faulkner, and Van Buren counties, as well as parts of Pope and Cleburne counties—was formed to encourage soil and water conservation. This was one of the first districts in Arkansas; it was granted a state charter on February 16, 1938.

Two Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps operated in Conway County during the Depression years. Company 1781 was active at Petit Jean Mountain from 1933 to 1938 and built and maintained the facilities at what was Arkansas’s first state park. Company 3789 carried out work such as terracing and sodding pastures under the supervision of the Soil Conservation District; the camp was closed in 1937 and moved to Berryville (Carroll County).

Despite its rural nature, Conway County did have some limited industry in the early twentieth century. The Morrilton Cotton Oil Mill was built in 1901 and operated for more than forty years. John B. Richardson started a soda bottling company in Morrilton in 1919, and ten years later, the Coca-Cola Company established a bottling plant in the same town. Other smaller industries were also present, most of then concentrated in Morrilton. The first hospital in Conway County opened in 1920.

World War II through the Faubus Era

Many Conway County men served in World War II. Lieutenant Nathan Gordon of Morrilton received the Medal of Honor in 1944 for using his Catalina patrol plane to rescue personnel shot down in combat over Kavieng Harbor on February 15, 1944. Gordon would go on to serve as lieutenant governor from 1947 to 1967, the longest tenure of anyone to hold the office in Arkansas’s history. Plumerville native John Yancey received a battlefield commission as a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps along with the Navy Cross during the Battle of Guadalcanal. During the Korean War, Yancey received a second Navy Cross for his actions at the Battle of Chosin Reservoir.

Conway County’s most famous resident, Winthrop Rockefeller of the famous Rockefeller family, bought a large amount of land on Petit Jean Mountain in the early 1950s and established a showplace home there. In 1964, he founded the Museum of Automobiles atop the mountain. In 1966, Rockefeller became the first Republican elected governor since Reconstruction. He served two terms and was widely recognized as the standard bearer of a new progressive spirit in Arkansas.

Conway County sheriff Marlin Hawkins played an outsized role in the politics of the state in the mid-twentieth century. Local newspaper publisher Gene Wirges helped expose corruption in the county.

Modern Era

In the 1960s, Conway County became home to four of Arkansas’s eighteen Titan II Missile silos. The Titan II was an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) placed in five Arkansas counties, as well as sites in Arizona and Kansas. The program was decommissioned in the early 1980s. Launch Complex 374-1 near Blackwell was deactivated on August 19, 1985; 374-3 near St. Vincent on August 6, 1986; 374-4 near Springfield on August 28, 1986; and 374-2 near Plumerville on September 16, 1986.

In 1968, Interstate 40 was completed, creating a main thoroughfare through previously rural Conway County. In 1966, construction began southwest of Morrilton on Lock and Dam No. 9, part of the McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System. Finished in 1969, it was renamed the Arthur V. Ormond Lock and Dam at a dedication ceremony on November 17, 1986. The dam has aided transportation and flood control on the Arkansas River.

Modern-day Conway County has twenty-one townships and three incorporated cities, as well as one incorporated town.

Education

The first recorded school in Conway County was a small log house at Lewisburg sometime before 1836. In 1867, the Male and Female Academy was operating at Lewisburg. Morrilton’s first public school for white children appeared in 1881, and its first school for black children was built in 1895. Soon, every community had a small school, many of only one room. The Springfield Male and Female Collegiate Institute operated for a number of years in the late nineteenth century.

In 1889, Morrilton founded the Male and Female College, which lasted until the late 1890s, when the building became part of the public school system. Arkansas Christian College was established in Morrilton in 1922. Two years later, it merged with a college in Harper, Kansas, and changed its name to Harding College. In 1934, it moved into the buildings formerly owned by Galloway Female College in Searcy (White County) and is now Harding University.

On May 26, 1965, years after the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, the Morrilton School Board abolished the black Sullivan High School and fired the staff, transferring the black students to the city’s predominately white junior and senior high schools. A federal lawsuit filed in 1972 and litigated into the 1980s found that school districts in the county had been consolidated based on race and not geographic considerations, forcing the redrawing of district lines to comply with federal law.

The county has at present four high schools and five elementary schools. It is also home to the University of Arkansas Community College at Morrilton.

Attractions

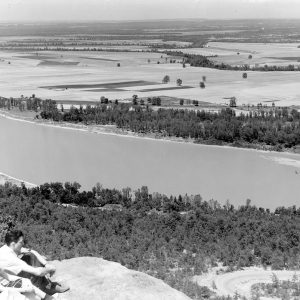

One point of interest in Conway County is the state park on Petit Jean Mountain; it was the first state park in Arkansas and is the most visited. Petit Jean State Park holds many attractions for tourists such as the Museum of Automobiles, Cedar Falls (one of the highest waterfalls in the South), and many hiking trails with scenic vistas of the river valley and mountains beyond. The Winthrop Rockefeller Institute is also located on Petit Jean Mountain. The Arkansas Sky Observatories operate two sites on the mountain.

The Depot Museum in Morrilton opened in 1981 and houses a collection of Conway County memorabilia. An old Missouri Pacific depot that closed in 1954, it was later purchased by the Conway County Historical Preservation Society and remodeled. Another attraction in the area is the Conway County Library, one of the few Carnegie Libraries remaining in the state. The Great Arkansas Pig Out, a two-day festival, is held in Morrilton each August.

For additional information:

Barnes, Kenneth C. Who Killed John Clayton? Political Violence and the Emergence of the New South, 1861–1893. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998.

Conway County, Arkansas: Our Home, Our Land, Our People. Little Rock: Historical Publications of Arkansas, 1992.

Glaze, Tom, and Ernie Dumas. Waiting for the Cemetery Vote: The Fight to Stop Election Fraud in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2011.

Historical Reminiscences and Biographical Memoirs of Conway County, Arkansas. Van Buren, AR: Press-Argus, 1967.

Santeford, Lawrence Gene, et al. Excavations at Four Sites in the Cypress Creek Basin, Conway County, Arkansas. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 1985.

Mary Ellen Guffey Brents

Morrilton, Arkansas

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Henderson State University

Carpet Rock

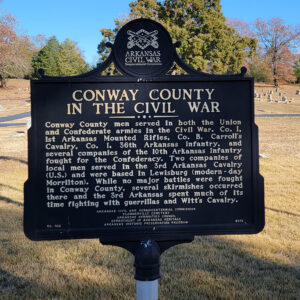

Carpet Rock  Civil War Marker

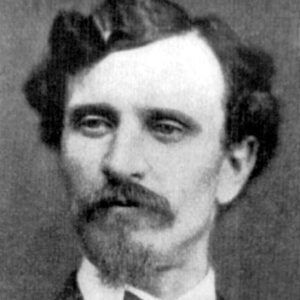

Civil War Marker  John Clayton

John Clayton  Climber Automobile

Climber Automobile  Conway County Courthouse

Conway County Courthouse  Conway County Library

Conway County Library  Conway County Map

Conway County Map  Fryers Ford Bridge

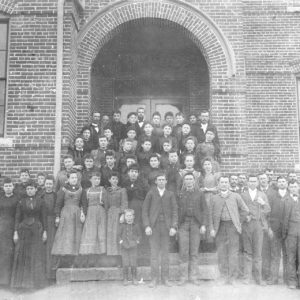

Fryers Ford Bridge  Morrilton Normal School

Morrilton Normal School  Morrilton Street Scene

Morrilton Street Scene  Old Guard Home Parody

Old Guard Home Parody  Petit Jean State Park

Petit Jean State Park  Petit Jean State Park View

Petit Jean State Park View  Petit Jean State Park

Petit Jean State Park  Petit Jean State Park

Petit Jean State Park  Springfield-Des Arc Bridge

Springfield-Des Arc Bridge  Jeff Williams

Jeff Williams

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.