calsfoundation@cals.org

Great Depression

In 1929, the United States economy began to retract, and commerce slowed. Over the next four years, the economic conditions in the country deteriorated, with the effects spreading around the world. The slowdown in the economy remained until 1939 and deeply impacted the people of Arkansas. The Great Depression began during the administration of Republican President Herbert Hoover, and its impact led to the election of Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) in 1932, which in turn brought forth multiple relief programs to support the citizens of the state and nation.

State Government

At the start of the Depression, Governor Harvey Parnell had recently completed his first term in office. Unexpectedly elevated to the post upon the resignation of Governor John Ellis Martineau in 1928, Parnell had served less than a year as the first lieutenant governor of the state and struggled to meet the economic challenges created by the Depression. Rather than utilizing the meager state resources on hand for relief, Parnell pushed programs to consolidate schools and improve roads within the state, adding to an already heavy debt burden.

Junius Marion Futrell was elected to replace Parnell as governor in 1932. A fiscal conservative, he cut the state budget by approximately half in his first year in office. Federal support through New Deal programs helped make up some of the difference, but Futrell’s reluctance to raise taxes put the state in a precarious position as the federal government demanded that Arkansas contribute to relief programs and stop the misuse of funds. Futrell supported the passage of Amendments 19 and 20 to the Arkansas Constitution in 1934, making the collection of additional taxes difficult, if not impossible. On March 14, 1935, the federal government stopped paying more than 400,000 Arkansans due to the inaction of Futrell and the Arkansas General Assembly to match payments made by New Deal programs. The state responded to the cessation of payments by creating the first state-wide sales tax. Futrell also signed legislation allowing betting on horse racing at Oaklawn in Hot Springs (Garland County) and dog racing in West Memphis (Crittenden County). Additional legislation passed during his administration allowed for the sale of alcoholic beverages throughout the entire state, providing another tax source and directly leading to the creation of the Arkansas State Police to enforce liquor laws. The implementation of these new taxes convinced the federal government to reinstate the stopped payments.

Carl Bailey succeeded Futrell as governor in 1937 and led the state during the remainder of the Great Depression. Bailey reorganized the Department of Public Welfare, allowing the unit to fully participate in federal relief programs. Late in his administration, Bailey openly feuded with Floyd Sharp, the state head of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), claiming that the workers employed by the federal organization operated as a machine to oppose his agenda. Efforts to investigate various New Deal projects in the state did not come to fruition, and Bailey lost his race for a third term in 1940.

Agricultural Impact

Coupled with the economic downturn, the state suffered multiple natural disasters during the Great Depression. Much of the eastern part of Arkansas continued to recover from the Flood of 1927 as the Depression began. The drought of 1930–1931 destroyed both the cotton crop used by many residents of the state for cash and the subsistence crops they relied on for food. Relief efforts from the federal and state governments were unorganized and made little impact. The administration of President Herbert Hoover tried to emphasize self-reliance and local relief efforts rather than providing food and other supplies for the destitute. The Red Cross created a food program in January 1931, but it was slow to get supplies to many parts of the state, leading to protests such as the England Food Riot. Over the next several months, the flow of food into the state improved and the Red Cross ceased distributions in April 1931, although the drought continued and families continued to struggle. Even when the Red Cross distributed food, it provided much less than the recommended amount to families in the state, with 519,000 people receiving assistance in February 1931. A lack of funding in St. Francis County led to the reduction of the food payment per person to just one dollar per month, down from two dollars per week.

The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA), passed by the U.S. Congress in May 1933, was a New Deal law that encouraged farmers to reduce the amount of certain cash crops that went to market by providing cash payments to plow up portions of the crop before harvest. The law saw the reduction of about thirty percent of the cotton crop in Arkansas in 1933, which in turn doubled the price of the crop from the previous year.

Payments from the AAA to planters were designed to be split between landowners and tenant farmers. Many planters illegally retained the funds, however, and evicted tenant farmers, leading to the establishment of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU). The STFU organized tenant farmers into locals, and union members experienced violent attacks for their efforts. More than sixty percent of farmers in 1930 Arkansas were tenants, with many bringing in less than $100 a year or finding themselves in debt to landowners at the end of the planting season. More than eighty percent of farmers in the state relied on cotton as a cash crop with little thought given to diversification. The invention of the first practical spindle cotton picker, tested in eastern Arkansas, led to the further depopulation of farms in the Delta.

The Drought of 1930–1931 finally broke, but the state soon faced the Flood of 1937. With millions of acres flooded, the state created camps for displaced residents. Most of those impacted by the floodwaters were agricultural workers from the eastern part of the state. The flood caused at least thirty-seven deaths and led to a meningitis outbreak in a relief camp near Jonesboro (Craighead County). The flood also killed thousands of farm animals. Because the flood occurred in January, it did not destroy any major planted crops, although the destruction of property slowed the economic recovery in the impacted areas.

Recovery from the Depression took more than a decade, with cotton prices finally reaching their 1929 level during World War II in the 1940s.

Population Shift

At the beginning of the Depression, Arkansas farmers struggled to provide for their families with minimal acreage under cultivation. On average, Arkansas farms had 14.3 acres of land under cultivation per person, while the national average was 32.4 acres. Too many people depended on minimal crops.

With the implementation of the Agricultural Adjustment Act, some landowners in the Arkansas Delta used the program to displace former tenant farmers or sharecroppers from their property. Using the cash subsidy received for plowing up acreage to purchase farm machinery, such as tractors, the property owners effectively replaced the tenants. This created a migratory impact, with approximately seven percent of the African American population leaving the state between 1930 and 1940—still lower than the 9.8 percent that had departed during the 1920s and the 24.1 percent who would leave in the 1940s (part of a broader population movement dubbed the Great Migration). However, the slowdown of the economy left many industries in the North with no need for additional workers, discouraging many from trying their luck in cities such as Chicago and Detroit.

White citizens departed the state in larger numbers but at a slightly lower rate, with 6.9 percent leaving in the 1930s. This compares with 11.3 percent in the 1920s and 16.5 percent in the 1940s. Between 1930 and 1940, the state gained just under 95,000 in total population, as compared to the approximately 102,000 gained in the 1920s. For the most part, residents of the state moved from farms to towns and cities during the Depression rather than in large numbers to other states.

The period between 1930 and 1935 saw a small increase in the number of farms operating in the state as unemployed workers returned to the land. The total number of farmers fell more than fourteen percent between 1935 and 1940, with the number of tenant farmers decreasing almost twenty-four percent and sharecroppers more than twenty-seven percent.

Banks

From 1930 to 1940, the number of banks operating in Arkansas decreased from 420 to 234. The majority of these failures occurred between 1930 and 1933, before the FDR administration took office. The largest bank in the state, American Exchange Trust Company of Little Rock (Pulaski County), failed in November 1930, leading to the subsequent failure of over fifty other banks in Arkansas. The creation of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) as part of the 1933 Banking Act helped bring stability to banks in the state and across the country.

Governmental Programs

Federal governmental intervention through multiple programs helped alleviate the economic hardships experienced by many Arkansans. The New Deal was a collection of programs created by the federal government to offer relief services to citizens across the country. States utilized federal funds and matched dollars with local tax collections. The programs gave millions of unemployed workers much needed jobs and pumped money into local economies, while creating public structures that served communities.

Following the election of FDR in 1932, Congress passed the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) on June 16, 1933, as part of the New Deal. One of the first impacts from the program in Arkansas came from the establishment of the Public Works Administration (PWA). The program offered grants to state and local governments to complete building projects and hire local workers. Millions of dollars poured into the state over the next eight years, and at least 235 projects were completed with assistance from the program. These included the Saline County Hospital, Robinson Center Music Hall, and buildings at what would become Arkansas Tech University in Russellville (Conway County) and Southern Arkansas University in Magnolia (Columbia County).

As the largest government program in the state, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) began operations in 1935, following an executive order by FDR. The program completed building projects across the state, including the Hot Spring County Courthouse, the Little Buffalo River Bridge, and the Hope Girl Scout Little House.

The reach of the WPA went well beyond building projects. The program implemented the Federal Writers’ Project, which hired writers to complete various works detailing the history and culture of the state. The project created guidebooks for each state, with the Arkansas edition appearing in 1941. The work detailed the history of the state and included sections on various topics such as education, industry, and travel information for potential visitors. The America Eats project collected information on the eating habits of people across the country, although the proposed book was never published. Detailing the lives of formerly enslaved people, the Slave Narrative Collection relied on writers associated with the project traveling across the South and other states to interview elderly African Americans about their experiences before and after Emancipation. The Arkansas section of the project was the largest of any single state, encompassing about one-third of the total interviews. The WPA also sponsored the Federal Theatre Project, which put on shows across the state, most notably in the aftermath of the 1937 flood.

The United States Department of the Treasury sponsored a program that brought art to federal buildings in communities across the country, most notably post offices. Twenty-one murals were created in post offices in Arkansas, painted by artists selected by the department. Many of the murals still exist in the early twenty-first century, either in their original location or in other public buildings, such as courthouses.

The National Youth Administration (NYA) completed several construction projects in the state, including the Arkadelphia Boy Scout Hut, the Izard County Courthouse, and the Old Highway 67 Rest Area in Clark County. The program completed projects much like the PWA and WPA but emphasized work for teenagers and young adults.

Created to help employ people during the winter of 1933–1934, the short-term Civil Works Administration (CWA) constructed several buildings across the state. Structures built by the administration that still exist in the twenty-first century include the Nashville American Legion Building in Nashville (Howard County) and the Bunch-Walton Post #22 American Legion Hut in Clarksville (Johnson County).

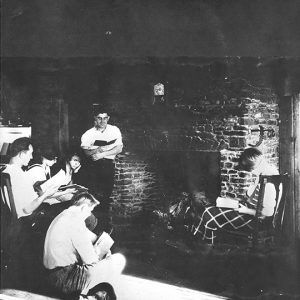

The New Deal organization that had the largest impact on the natural areas of the state was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). Created in March 1933, the CCC offered young men between the ages of seventeen and twenty-eight job opportunities, along with housing and board. They were paid $30 per month, although $25 of the funds were required to be sent to their families. In addition to earning money and receiving housing, the men also were offered specialized training and took educational classes. The men lived in camps, typically located in rural parts of the state. Working on projects on both federal and state land, the workers completed a wide range of projects from planting trees to building dams and cabins. Many of the structures constructed by the CCC continue to be utilized in the twenty-first century, including the Crossroads Fire Tower and multiple buildings and structures at Mount Nebo, Petit Jean, Lake Catherine, and Crowley’s Ridge State Parks. Several of the former camps are also listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Farm Resettlement Projects

With thousands of destitute farmers across the country, the federal government created resettlement projects in an effort to make these families self-sufficient. The Arkansas Rural Rehabilitation Corporation created several resettlement projects in the state, including at Dyess (Mississippi County). The community, designed for only white residents, included 500 simple farmhouses, with each family also provided with a privy, barn, and chicken coop. Seeds and other planting supplies were purchased communally, while loans were available for the farmers to purchase the home, a plot of land on which to farm, and other necessary items, with the loan paid back by the farmer after the sale of the first crop.

Other resettlement projects constructed in the state included Clover Bend (Lawrence County), Lakeview Resettlement Project (Phillips County), and Lake Dick (Jefferson County).

Education

Elementary and secondary schools struggled to operate in the state in the early years of the Depression. A lack of funding prevented the state from operating a robust school system, with Arkansas students attending class for 145 days compared to a national rate of 171 days. In 1929, the average annual salary for teachers in Arkansas stood at $667 while the national average was $1,364. By the 1933–34 academic year, Arkansas salaries had fallen to $465, with many of the teachers paid by warrants issued by local districts short on cash.

Relief efforts reached school children, with the WPA providing hot lunches for students. Initially created to feed just those on relief, the program expanded to include all children when officials realized that the food encouraged learning.

Higher education in the state suffered from a lack of funding at the beginning of the Depression. Public colleges offering four-year degrees in the state included the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County), Arkansas State Teachers College (now the University of Central Arkansas) in Conway (Faulkner County), Arkansas AM&N (now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff) in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), and Henderson State Teachers College (now Henderson State University) in Arkadelphia (Clark County), which began operations in July 1929. These institutions operated alongside several public junior colleges.

The Depression did not have an immediate impact on the budgets passed by the General Assembly as it met in early 1929 and approved the spending for each institution through June 1931. In early 1931, however, the General Assembly reduced funding for the schools, with Henderson seeing a ten percent reduction in state support and the University of Arkansas seeing an eight percent reduction. Only with the distribution of federal relief dollars did the budgets return to normal after several years of reductions.

Enrollment at many of the institutions remained steady or grew during the Depression, with some year-to-year fluctuations. A notable legacy of the Depression on the campuses across the state were the numerous buildings and other structures constructed using federal funds through various programs, such as the WPA. Federal funding helped expand some existing facilities, including on what is today known as Donald W. Reynolds Razorback Stadium at UA.

Commonwealth College operated near Mena (Polk County) during the Depression, opening in 1924 following a move from Louisiana. The college operated as an education and work experiment that required students to complete four hours of daily labor along with coursework. The students and staff of the college worked with members of the STFU and supported various labor efforts across the country. The college operated until 1940, when it closed in the face of a fine for actions deemed to be un-American.

African Americans

The African American experience during the Great Depression in Arkansas differed from that of many of the white citizens of the state. Many Black residents lost their jobs before their white counterparts, leading to the phrase “Last hired, first fired.” Working lower-paying jobs, African Americans typically found their wages or hours reduced or found themselves replaced by white workers now willing to fill jobs typically held by Black workers. By 1930, the federal government estimated that seventeen percent of the white population and thirty-eight percent of the Black population required assistance.

The New Deal programs often did not offer support for African Americans, focusing on white citizens. The creation of Social Security did not have a substantial positive impact on the Black community, with agricultural workers and domestic servants excluded from the initial act passed in 1935. A few projects did assist African Americans, including the Lakeview Resettlement Project and the Desha Farms and Townes Farms Resettlement Projects.

Educational facilities for African Americans suffered from reduced funding during the Depression. Arkansas AM&N, founded in 1875 as a four-year college, operated from around 1903 until the fall of 1929 as only a secondary school with no college-level coursework offered. Funds for Black students were often diverted to white schools; for example, an estimate from the town of Crawfordsville (Crittenden County) put the difference at fifty-seven dollars for white students for every dollar spent on African American students.

For additional information:

Chesnutt, E. F. “Rural Electrification in Arkansas, 1935–1940: The Formative Years.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 46 (Autumn 1987): 215–260.

Cobb, William H. “From Utopian Isolation to Radical Activism: Commonwealth College, 1925–1935.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 32 (Summer 1973): 132–147.

–––. “The State Legislature and the ‘Reds’: Arkansas’s General Assembly v. Commonwealth College, 1935–1937.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 45 (Spring 1986): 3–18.

Greenberg, Cheryl Lynn. To Ask for an Equal Chance: African Americans in the Great Depression. Blue Ridge Summit: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2009.

Hicks, Floyd W., and C. Roger Lambert. “Food for the Hungry: Federal Food Programs in Arkansas, 1933–1942.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 37 (Spring 1978): 23–43.

Holley, Donald. “Carl E. Bailey, the Merit System and Arkansas Politics, 1936–1939.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 45 (Winter 1986): 291–320.

———. “Leaving the Land of Opportunity: Arkansas and the Great Migration.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 64 (Autumn 2005): 245–261.

———. “The Second Great Emancipation: The Rust Cotton Picker and How It Changed Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 52 (Spring 1993): 44–77.

Lambert, Roger. “Hoover and the Red Cross in the Arkansas Drought of 1930.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 29 (Spring 1970): 3–19.

Latimer, Franklin Allen. “Arkansas Listings in the National Register of Historical Places Allegorical Representations in Arkansas Post Office Murals.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 61 (Spring 2002): 88–92.

Ledbetter, Calvin R. “Carl Bailey: A Pragmatic Reformer.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 57 (Summer 1998): 134–159.

Murray, Gail S. “Forty Years Ago: The Great Depression Comes to Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 29 (Winter 1970): 291–312.

Rison, David. “Arkansas during the Great Depression,” PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 1974.

———. “Federal Aid to Arkansas Education, 1933–1936.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 36 (Summer 1977): 192–200.

Stockley, Grif. Ruled by Race: Black/White Relations in Arkansas from Slavery to the Present. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2009.

Watkins, Patsy G. “Same People, Same Time, Same Place: Contrasting Images of Destitute Ozark Mountaineers during the Great Depression.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 70 (Autumn 2011): 288–315.

Webb, Pamela. “Business as Usual: The Bank Holiday in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 39 (Autumn 1980): 247–261.

———. “By the Sweat of the Brow: The Back-to-the-Land Movement in Depression Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 42 (Winter 1983): 332–345.

Whayne, Jeannie M. A New Plantation South: Land, Labor, and Federal Favor in Twentieth Century Arkansas. Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 1996.

Yard, Alexander. “‘They Don’t Regard My Rights at All’: Arkansas Farm Workers, Economic Modernization, and the Southern Tenant Farmers Union.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 47 (Autumn 1988): 201–229.

David Sesser

Southeastern Louisiana University

CCC Enrollees

CCC Enrollees  Civilian Conservation Corps Camp

Civilian Conservation Corps Camp  Commonwealth Students

Commonwealth Students  Cotton Pickers

Cotton Pickers  Dyess Buildings

Dyess Buildings  Lakeview Children

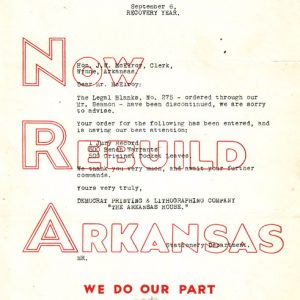

Lakeview Children  Now Rebuild Arkansas

Now Rebuild Arkansas  Sharecropper House

Sharecropper House  WPA Plaque

WPA Plaque

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.