calsfoundation@cals.org

Roads and Highways

From the creation of Arkansas Territory to present-day Arkansas, road construction has been critical to the development of the state. The construction of roads helped to increase the population of the state in the early years by improving access to areas west of the Delta. The Delta, made up of swamplands, streams, and rivers located in eastern Arkansas, had always been a major obstacle to travel west from the Mississippi River. The earliest routes used for transportation in Arkansas were rivers and creeks due in large part to the number of open waterways in Arkansas and the fact that travel on foot was difficult in swampy areas. These waterways were used by Native Americans and early explorers. Later, Indian trails were used as the base for the earliest roads. The earliest types of roads constructed in the state were military roads and local “public” roads.

Military roads were constructed in Arkansas from the 1820s to the mid-1840s and used for troop movement. Some of the early trails in Arkansas were converted into military roads in the early 1820s. Two examples of these trails are the Southwest Trail, first used in the 1760s, and John Pyeatt’s Road, which Pyeatt built in 1807 from the Crystal Hill (Pulaski County) area to an Indian trail leading to Arkansas Post (Arkansas County).

One of the most important military roads in Arkansas was the Memphis, Tennessee, to Little Rock (Pulaski County) road. Crossing the swamps of eastern Arkansas had always been a hurdle to population growth in the state. The construction of a road from Memphis to Little Rock opened a conduit that would allow settlement in western parts of the state. By 1827, sixty miles of the road had been constructed from Memphis west toward Little Rock, with the rest completed by the mid-1830s. Typical specifications for these roads called for all brush and saplings six inches or less in diameter to be cut at ground level, all trees between six and twelve inches to be cut within four inches of the ground, and all trees over twelve inches to be cut within eight inches of the ground. With these specifications, only horses and light wagons were able to transverse the roads, and during the rainy seasons, they became impassible.

Landowners under the authority of the county courts constructed local roads during territorial times and early statehood. These local roads were considered “public” roads, meaning that they were under the authority of the courts and open to all travelers. These public roads were constructed in Arkansas from the early 1820s to 1907. The earliest of these roads were affectionately known as “roads to nowhere” by travelers to the area because these roads did not connect towns but were farm-to-market roads. Generally, they began at a field or creek and continued on to a house or tavern, although sometimes they would end at a military road. Territorial law stated that when twelve landowners petitioned the county court for a road, the court would appoint three to five commissioners to determine the best place for the road, and all men between the ages of sixteen and forty-five years old, as well as all male slaves of the same age, would be required to work on the road in their township as assigned by the court. An interesting habit of Arkansas road users was to make a turnout around any obstacle blocking the road rather than removing said obstacle, which were mostly fallen trees. Sometimes, the old turnouts would be blocked, and a new one would be made. This phenomenon can be observed on a number of General Land Office Plat maps from the mid-1830s into the early 1850s.

As Arkansas became a state, two things happened concerning roads; the first was Act 167 of 1836, which stated that all public roads laid out in pursuance of the laws of the territory or state of Arkansas were declared public highways. This act codified the existing territorial laws and placed the responsibilities of construction and maintenance of the public highways in the hands of the county courts. Secondly, the U.S. government, in an effort to improve federal mail service, began a new wave of road construction and reconstruction of the existing military roads. These post roads were constructed from 1836 to the late 1860s under local contract at federal expense. The cost of this work was split by the U.S. Post Office and the Department of Agriculture. These roads provided a network for communication and commerce in areas with no steamboat access. Along with the construction of new roads, the old military roads were reconstructed as part of this system. The first of these roads, called “post roads” because they were built to facilitate the delivery of mail, in Arkansas was built very soon after statehood between Batesville (Independence County) and Lewisburg (Conway County). It utilized parts of the old Fort Smith (Sebastian County) to Little Rock military road, as well as new construction.

From 1836 to 1871, road construction in Arkansas did not change. Post roads continued to be constructed and improved, while public highway construction began to center on connecting the “roads to nowhere” to the post road system. At no time did the level of maintenance required to keep the public highways in good condition receive any serious consideration from the state or county governments. Neither the state government nor local governments had money available for use on road maintenance because Arkansans would not pay long-term taxes for the maintenance of roads. This attitude applied not only to the local roads but to military and postal roads as well. This widely held attitude of “Spend the money to build roads, but keep the cost of maintenance a local responsibility” is in large part responsible for Arkansas’s reputation for having some of the worst roads in the nation. Citizens in other states were at least willing to pay local taxes for the upkeep of their major roads. This would be an ongoing problem until 1916, when the federal government began distributing federal funds to all states for road construction.

In 1871, legislation (Act 26) was enacted that re-codified the existing road laws of the state under the new constitution being drafted as part of Arkansas’s re-admittance to the Union. The most important part of this legislation stated that all roads in the state that had been built under the law, all roads built by the United States, and all public roads in the state known as military roads were declared public highways under the jurisdiction of the individual county governments.

By 1871, the backbone of today’s road system was in place; although a number of roads were built over the next hundred years, they were only additions to the existing network. The largest challenge facing the counties was the condition of the roads. Even though there was a network of roads, they were not built to connect anything more than local towns within a particular county. Local interests dictated where the roads were constructed, and developing improved inter-county travel was not a priority because people still relied on the deteriorating system of old military and post roads for travel between them. This lack of maintenance was a direct result of a lack of a funding source. No one wanted to pay for maintenance on roads they did not use and were even unwilling to pay a county road tax when it became an option in 1899 (Act 200). This localism and lack of maintenance were to come to a head in the early part of the twentieth century.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, bicycling had become popular, and many bicyclists were unhappy over the condition of the roads they were attempting to travel. In 1892, bicyclists began the Good Roads Movement, which pushed for better roads and improved maintenance over the next ten years. While the Good Roads Movement started as a national movement, by 1896, Arkansas had developed a state branch of the movement supported by groups in most of the counties. By 1907, the state legislature had become involved in the funding debate. Act 144 (the Arnold Road Bill) passed by the Arkansas General Assembly in 1907 allowed the counties to set up road improvement districts at the request of a majority of landowners along a road but few improvement districts were created under this bill due to various legal questions regarding funding.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, rumblings about the condition of Arkansas’s roads came to a head. Converging factors were the growth of the Good Roads Movement, mass production of the automobile, and the issues of funding construction and maintenance of the roads. By 1913, the Good Roads Movement had become a national force that advocated for better roads around the country. This and the explosive growth of automobile use in Arkansas between 1910 and 1920 added pressure to the already hot issue of improved roads and their maintenance. In 1913, another attempt was made by the state legislature to create road improvement districts (Act 302), but again, issues regarding the use of bonds to finance these improvement districts negated the effort. Also under this act, the Arkansas Highway Commission was created, which was the first step in creating a statewide authority to manage road construction and maintenance. The commission’s first responsibility was to furnish advice and assistance to the road improvement districts.

Finally, in 1915, the state legislature passed Act 338 (the Alexander Road Improvement Law), which fixed the problems associated with using bonds to finance road improvement districts. From 1915 to 1927, the state saw an explosion of road improvement districts, with 527 districts created during that time. Localism again reared its head as the driving force behind the road improvement districts. While these districts constructed very good roadways, they lacked any plans for the maintenance of the roads and failed to participate in any statewide or regional traffic planning.

In 1916, the federal government weighed in on the issue of funding road construction with the first federal aid road bill. These funds were apportioned to the states to improve rural roads used for postal delivery. This bill also required each state to have a highway agency with engineers to oversee the distribution of the federal funds. Although the federal monies increased in 1919 with the new federal bill, paying off the road improvement district bonds had become a problem. By 1922, Arkansas landowners were saddled with the enormous debt of the improvement districts, while the roads created by these districts slowly devolved into muddy trails. The day of the road improvement district was quickly coming to a close.

After five years of distributing federal aid, the federal government had learned the futility of the unplanned, haphazard approach to road construction the districts represented. So, in 1921, a new federal aid bill was passed that changed the way that states constructed roads. The new bill required states to create a designated system of state highways and ensured that the construction of roads was to be managed by a state highway department. Local governments would have to guarantee continuing proper maintenance of the roads once they were constructed if they were to receive the much larger share of federal funds available. In response to this bill, Governor Thomas Chipman McRae and a special session of the Arkansas General Assembly passed Act 5 (the Harrelson Road Law) in 1923. This law created a 6,700-mile state highway system, along with the Arkansas Department of Transportation.

While Arkansas finally had a state agency to manage road construction and an unimpeded flow of federal funds to help improve the state highway system, the problem of paying off the improvement district bonds still remained the last great hurdle to a road system fully managed and maintained on a statewide level. In the summer of 1926, the debt of the improvement districts began to cause foreclosures of mortgages to meet tax payments. These foreclosures would only continue to increase if something was not done. This issue was at last remedied by the passage of Act 11/27 (the Martineau Road Law) in 1927. The most important aspect of this bill was the state’s assumption of the improvement districts’ bond obligations. Finally, the leaders of the state had recognized the equity of placing the burden of fiscal responsibility for roads onto the road users and relieving the owner of property adjacent to the road of the improvement district taxes. Even though the citizens of the state had been relieved of the bond obligations, the future of road construction would still be bumpy. The Great Depression and World War II both depleted taxes and materials and caused the state to stop all but the most critical road construction so that maintenance on the existing roads could continue.

Following World War II, a tremendous economic expansion began across the country. One of the issues this expansion highlighted was the need for a national transportation network that would allow cheap, easy travel from coast to coast. As a result of this and the need to create a national defense transportation network, the interstate system was approved in 1956. To ensure the connectivity of the system across the country, the federal government became involved in road design and construction by providing the majority of the funds required for planning, design, and construction. The first stretch of interstate completed in Arkansas was Interstate 30 running from Little Rock southwest to Texarkana (Miller County) on to Dallas, Texas. Although Interstate 30 is considered the first interstate built in Arkansas, it must be noted that construction of Interstate 40 was taking place at the same time.

As recently as the 1970s, some state highways in Arkansas were still unpaved, but with the passage of financing programs (such as those in 1991 and 1998) by the citizens and legislature, the state has paved all but one of those state highways. Since the mid-1980s, Arkansas has consistently been placed in the top twenty states in federal spending for roadways. This is due in large part to the number of miles of state highway (over 16,000) Arkansas must maintain. In 1999, the citizens voted to use bonds to finance an interstate reconstruction program. This was the first time bonds had been used to finance road construction in Arkansas since the late 1940s. The interstate rehabilitation program has reconstructed the interstates in Arkansas to be some of the country’s best.

Today, Arkansas has a system of state highways, county roads, and interstates that has descended from the original roads constructed in the early decades of the state. These roads are managed at the state level so that the planning of a contiguous and accessible system of roads can continue into the future.

For additional information:

Brown, Carl E. “Improving the way to the Land of Opportunity: Internal Improvements in Antebellum Arkansas.” PhD diss., University of Memphis, 2012. Online at https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/etd/549/ (accessed January 2, 2024).

Hanson, Gerald T., and Carl H. Moneyhon. Historical Atlas of Arkansas. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1992.

Herndon, Dallas Tabor. Centennial History of Arkansas. vol. 1. Chicago: S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1922.

Historic Review: Arkansas State Highway Commission and Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department, 1913–1992. Little Rock: Arkansas State Highway Transportation Department, 1992.

Hume, John. “The Automobile Age in Arkansas.” 12-part series. Arkansas Highways 23–25 (Spring 1977–Winter 1979).

Merritt, Jim, and Marion Devine. “The Arkansas-Louisiana Highway: The Predecessor of U.S. Highway 65.” Programs of the Desha County Historical Society 11 (Spring 1985): 4–21.

Robert W. Scoggin

Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department

Homer Adkins

Homer Adkins  Arkansas Highways

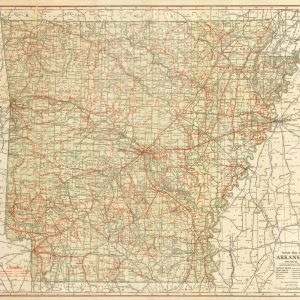

Arkansas Highways  Arkansas Road Map, 1918

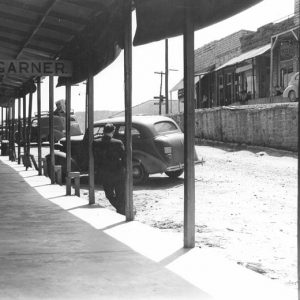

Arkansas Road Map, 1918  Beebe Street Scene

Beebe Street Scene  Calico Rock Street Scene

Calico Rock Street Scene  Clarksville Street Scene

Clarksville Street Scene  Cove Lake

Cove Lake  Decatur Street Scene

Decatur Street Scene  Harrison Roads

Harrison Roads  Highway 14 Construction

Highway 14 Construction  I-40 Dedication

I-40 Dedication  I-630

I-630  Leachville Street Scene

Leachville Street Scene  Light

Light  Military Road

Military Road  Norfork Dam

Norfork Dam  Rogers Street Scene

Rogers Street Scene  St. Francis River

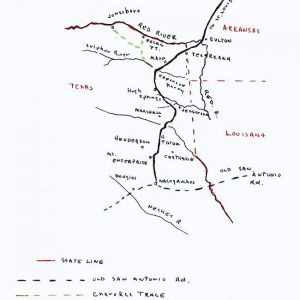

St. Francis River  Trammel's Trace Map

Trammel's Trace Map

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.