calsfoundation@cals.org

Emancipation

By 1860, about twenty-five percent of Arkansas’s population was enslaved, amounting to more than 111,000 people. The emancipation of these people in Arkansas took place as a result of the American Civil War, their freedom achieved due to the decisions made by Union military leaders, President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, and the actions of the slaves themselves. Slavery’s abolishment meant more than simply the loss of human property and the end of a labor system—it ended a social relationship that had defined the state’s early development.

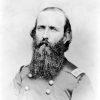

The process of emancipation in Arkansas began before Lincoln’s formal Emancipation Proclamation. Finding that Confederates had used slave labor to create physical obstacles in his path across Arkansas in 1862, Union general Samuel R. Curtis saw an opportunity to undermine the Confederate effort in Arkansas. Concerned that the slaves might be recaptured and used against him, and being interested in employing them for the Union cause, Curtis drew on the authority of earlier “Confiscation” acts by Generals William Tecumseh Sherman and Ulysses S. Grant. Issuing certificates of freedom to hundreds of the “contraband” fugitives, Curtis proclaimed permanent freedom for slaves who had been used against the Union. Curtis differed from other Union officers fighting in the South in that he favored greater military involvement in helping fugitive slaves. Word spread among Arkansas’s slaves, and when Curtis’s army arrived at Helena (Phillips County), so did the trail of slaves who had been following the army in hope of freedom and protection. This area of eastern Arkansas continued to be a popular destination for runaway slaves in Arkansas, and settlements of freedmen multiplied. C. C. Washburn, commander of the Post of Helena, wrote that return to their homes was not an option for former slaves even if they wished it, and that to ask them to do so would have been unreasonable considering the dangers. In charge of “contraband” camps in eastern Arkansas was Colonel John Eaton.

More than 5,000 of Arkansas’s former slaves enlisted in the Union army. They often labored in ditches or stood as guards, but some saw military action and were praised for their performance. Men and women alike sought work in order to provide for themselves and their families while the Union army, as well as white farmers in the area, needed their labor. General Curtis allowed former slaves to sell Confederate cotton or work for the Union army for wages. The presence of formerly enslaved women and children was generally seen as a burden by the Union forces in eastern Arkansas. Curtis, feeling overwhelmed by the immense “cloud” of slaves seeking protection at his post, authorized the removal of many former slaves from Arkansas to the North. More than 1,000 made the move.

Many Arkansas freedmen not in military service worked on plantations owned by loyal white Arkansans or ex-Confederates, as well as plantations leased by Northerners or other whites. During the war, free black labor served to continue cotton production in a way that benefitted the Union and the local economy while undermining the Confederacy. In time, freedmen and freedwomen were able to lease land themselves. For the most part, the system set up by Union officials (and then taken up by the Freedmen’s Bureau) meant former slaves worked on large farms rather than breaking up land into several smaller holdings. Freedmen had hoped for land and autonomy, but these hopes were often circumscribed. The plantation system set up by the Union in Arkansas was driven primarily by profit and did not serve to cultivate freedom or independence among former slaves. The system of contracts was ripe for manipulation against the favor of African Americans, who were mostly illiterate. The Freedmen’s Bureau (officially, the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands) took over overseeing the work of former Arkansas slaves in June 1865. The bureau took the view that the most effective way to encourage hard work among freedmen was to have them buy or lease smaller portions of land. This system of agricultural work for freedmen was a precursor to the system of sharecropping that developed later.

Though freedom had come to a great portion of Arkansas’s bondspeople during the course of the war, it did not necessarily bring prosperity or security. The camps housing families of freedmen in eastern Arkansas were plagued with disease and unsanitary conditions. Many people were inadequately clothed and housed. The Union army tried to ameliorate these conditions by setting up a system that included a “negro hospital,” complete with at least one surgeon set to the task of administering to former slaves. Civilian volunteers from the North also came to help ease the suffering. Freed slaves who were employed often had difficulty securing promised compensation for their work. They also endured theft and violence at the hands of whites. A. W. Harlan described the scene in one camp at a Union-controlled woodyard, pointing out that though some freedmen there were in bad health—and most had little bedding and inadequate shelter—some were heartened by their religious hope and the opportunity for wages.

President Lincoln’s initial Emancipation Proclamation, announced in September 1862, warned that areas still in rebellion at the beginning of the next year would see their slave property officially freed by the U.S. government. The order was meant to weaken the Confederacy and strengthen the moral high ground for the Union. On January 1, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect, shifting the emphasis of the Civil War from a fight to save the Union to a fight for freedom. Arkansas’s capital city of Little Rock (Pulaski County) fell to Union forces in September 1863. Arkansas then had two state governments: the Union-controlled government in Little Rock (Pulaski County) and the Confederate one in Washington (Hempstead County). In 1864, the Unionist government adopted a new state constitution that abolished slavery, but although President Lincoln approved of the document, it was never recognized by the United States Congress. Confederate Arkansas fell into disarray in the spring of 1865, and the Trans-Mississippi South officially surrendered to the Union on June 2, 1865.

Slaves in Arkansas who had not had the opportunity to seek freedom in the course of the war received the news of Confederate defeat and their own freedom with enthusiasm and relief. Though whites were often devastated or angry, slaves celebrated their freedom immediately and continued to commemorate their emancipation in public celebrations. Some newly freed families chose to stay and work for their former masters, while many made the decision to look for work elsewhere.

Because Arkansas slaveholders understood all along the threat of the war to their ownership of slave property, many fled the state, like Arkansas’s largest slaveholder, Elisha Worthington of Chicot County, who moved with his slaves to Texas. Slave narratives provide evidence that many whites in Arkansas sought to hold onto slavery by ignoring emancipation for as long as possible. Indeed, the defeat of the Confederacy meant the loss of more than $100 million of slave property. Economic interests and racism made it difficult for many white Arkansans to accept the end of slavery, and race relations in Arkansas continued to be a problem for generations.

For additional information:

Berlin, Ira, et al., eds. Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861–1867. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1982, 1985, 1990, 1993.

Finley, Randy. From Slavery to Uncertain Freedom: The Freedmen’s Bureau in Arkansas, 1865–1869. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1996.

Jemison, Elizabeth. “Protestants, Politics, and Power: Race, Gender, and Religion in the Post-Emancipation Mississippi River Valley, 1863–1900.” PhD diss., Harvard University, 2015.

Jones, Kelly Houston. “Freedom at the ‘Pine Bluffs,’ 1864: A Research Note.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 77 (Spring 2018): 45–51.

———. A Weary Land: Slavery on the Ground in Arkansas. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2021.

Lankford, George E., ed. Bearing Witness: Memories of Arkansas Slavery: Narratives from the 1930s WPA Collections. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2006.

Moneyhon, Carl. The Impact of the Civil War and Reconstruction on Arkansas: Persistence in the Midst of Ruin. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994.

———. “Race and the Struggle for Freedom: African American Arkansans after Emancipation.” In Race and Ethnicity in Arkansas: New Perspectives, edited by John A. Kirk. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2014.

Nichols, Ronnie A. “Emancipation of Black Union Soldiers in Little Rock, 1863–1865.” Pulaski County Historical Review 61 (Fall 2013): 76–85.

Poe, Ryan M. “The Contours of Emancipation: Freedom Comes to Southwest Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 70 (Summer 2011): 109–130.

Rodrigue, John C. Freedom’s Crescent: The Civil War and the Destruction of Slavery in the Lower Mississippi Valley. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2023.

Kelly Houston Jones

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.