calsfoundation@cals.org

Civil War Recruitment

When the American Civil War began in April 1861, the recruitment of soldiers was not a problem for either side. Partisans of both the Union and the Confederacy were so confident that victory could be achieved in a few months that young men volunteered by the thousands to make sure that they did not miss out on the war. The turnout was so much greater than expected that the major problem facing the War Departments of both the Union and Confederacy was not the enlistment of soldiers but the procurement of food, clothing, and armaments to sustain them. The recruitment and organization of both armies began even before hostilities commenced, which was necessary given the size and condition of both armies.

The United States of America had a standing army of 16,000 men in early 1861, with most of these soldiers serving in poorly equipped military outposts west of the Mississippi River and as far away as California and Oregon. Many of these soldiers, especially officers, were resigning their commissions as their individual states seceded from the Union. The Confederate army did not yet exist. The procedures for the recruitment of troops for both armies originated in the Militia Act of 1792, and its revision of 1795. The first of these measures legislated that all white men of sound body between the ages of eighteen and forty-five were legally obligated to serve in the militia of their state. The second reinforced the commander-in-chief’s authority to call these troops to federal service.

Delegates from six of the seven states of the Deep South convened in Montgomery, Alabama, in early February 1861 and founded the Confederate States of America. On February 8, delegates ratified a provisional constitution. This same day, the Federal arsenal in Little Rock (Pulaski County), was seized by unauthorized forces, despite the fact that Arkansas was still part of the United States. The following day in Montgomery, the Provisional Congress nominated Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi as provisional president of the Confederate States of America. Davis was inaugurated on February 18. Ten days later, the Confederate legislature granted Davis broad authority over the fledgling nation’s military affairs. Specifically, Davis was “authorized and directed to assume control of all military operations in every State.” This legislation also granted Davis control over the arms, munitions, and other materiel seized at Federal arsenals by Confederate states since the secession of South Carolina in December 1860. Moreover, the president was to have authority, for twelve months or more, over any troops who were tendered by the states or who volunteered to serve with the consent of their governors. These troops were to serve with their elected officers in the Provisional Army of the Confederate States.

Initially, President Davis was reluctant to use such powers because he did not want to exacerbate tensions with the Federal government in Washington DC. After President Abraham Lincoln took the oath of office on March 4, 1861, however, the Confederate government moved more quickly to build its military. Two days after Lincoln’s inauguration, the Confederate Provisional Congress enacted two pieces of legislation that expanded the military powers of President Davis. The commander-in-chief was now empowered to call state militia units into Confederate service—not merely accept those units who volunteered or were tendered by state governors—for up to six months. In addition, he had the authority to accept 100,000 volunteers into the Provisional Army for up to twice that period. The second piece of legislation passed that day created the Army of the Confederate States of America. The Provisional Army was intended to be a short-term response to the new nation’s immediate military needs; the Regular Army was to be the Confederacy’s permanent, longstanding military apparatus. Virtually all of the approximately one and a half million men who served in the Confederate military during the Civil War served in the Provisional Army. Both the provisional and regular armies are known colloquially as the Confederate army.

The first great influx of recruits into the Confederate army came after the surrender of Fort Sumter and President Lincoln’s subsequent call for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the rebellion. The troops Lincoln called into Federal service on April 15 were to be recruited by the individual states, with the governors of all states currently remaining in the Union given a quota of recruits to provide. When Secretary of War Simon Cameron notified Governor Henry Massie Rector of his allotment, the Arkansas governor responded on April 22: “In answer to your requisition for troops from Arkansas, to subjugate the Southern States, I have to say that none will be furnished.” The Arkansas militia seized control of Fort Smith (Sebastian County) the following day, after it was abandoned by Federal forces.

As tensions escalated in early May, the Confederacy responded with greater calls for recruits. Throughout this crisis, Arkansans wavered over secession for several reasons. First, citizens in the mountainous regions of the state were predominantly non-slaveholding and pro-Union. Second, residents across the state worried that seceding would mean an end to Federal protection against hostile Native Americans. Furthermore, the state would also be vulnerable to Federal troops from the north should Missouri not secede. Despite these considerations, Arkansas ratified its Ordinance of Secession on May 6, 1861.

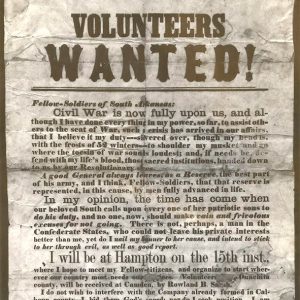

Arkansas contributed recruits to both Federal and Confederate service in the Civil War. Soldiers were most often recruited by local communities, and most regiments were created out of companies recruited at the local level. Men joined for myriad reasons: to defend slavery or the privileges associated with whiteness; for travel and adventure; to defend the Union; to protect their families and property; or to avoid a loss of honor and status within their local community—for example, Henry Morton Stanley, while living in Arkansas on the verge of war, received a packet of women’s underwear for having not yet enlisted in the Confederate cause. Sometimes, Confederate recruitment could be hampered by the larger, national picture. However, noted recruiter Brigadier General William Joseph Hardee encountered a fear among many recruits that entrance into the Confederate ranks might result in their transfer from the state.

As early as summer 1862, the Federal army was increasingly successful in recruiting near Helena (Phillips County) after Union forces penetrated the area, but Arkansans with Union sympathies also mustered into service in Springfield, Missouri, in July 1862 as the First Arkansas Cavalry. The recruiting of Union troops became more widespread as the war progressed and Arkansans either became disenchanted with the Confederacy or were able to express their true allegiance with the loss of Confederate control in a given region. The state had a population of 324,335 white citizens according to the 1860 census. Of these, approximately 60,000 served in the Confederate military and 14,000 in the Union. Recruits served predominantly in the army and fought in all three branches—infantry, artillery, and cavalry—in various theaters of operation. There was also a sizable number of African-American recruits into Federal service; six Black volunteer regiments were organized in Helena starting in April 1863. Other Union-controlled cities such as Fort Smith and Fayetteville (Washington County) also served as centers of recruitment until the end of the war.

For additional information:

Current, Richard N. Lincoln’s Loyalists: Union Soldiers from the Confederacy. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1992.

Evans, Clement A., ed. Confederate Military History: A Library of Confederate States History, in Twelve Volumes, Written by Distinguished Men of the South. Vol. 10. New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1899.

Glatthaar, Joseph, T. General Lee’s Army: From Victory to Collapse. New York: Free Press, 2008.

Robertson, Brian K. “Men Who Would Die by the Stars and Stripes: A Socio-economic Examination of the 2nd Arkansas Cavalry (US).” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 69 (Summer 2010): 117–139.

Thomas, David Y. Arkansas in War and Reconstruction. Little Rock: Arkansas Division, United Daughters of the Confederacy, 1926.

Keith Muchowski

New York City College of Technology (CUNY)

Civil War Refugees

Civil War Refugees Conscription (Civil War)

Conscription (Civil War) Union Occupation of Arkansas

Union Occupation of Arkansas Unionists

Unionists Recruitment Poster

Recruitment Poster

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.