calsfoundation@cals.org

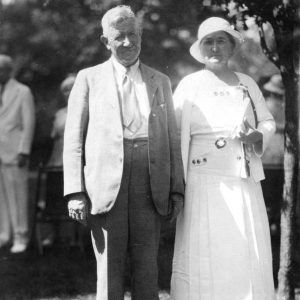

Junius Marion Futrell (1870–1955)

aka: J. Marion Futrell

Thirtieth Governor (1933–1937)

Junius Marion Futrell, the thirtieth governor and a circuit and chancery judge, had the misfortune to be governor during the Great Depression. Hamstrung by the state’s financial predicament and by his philosophy of limited government, Futrell has not ranked high in the estimation of historians.

Born on August 14, 1870, to Jepthra Futrell and Arminia Levonica Eubanks Futrell in the Jones Ridge community (Greene County), J. Marion Futrell was the second of three children. His father, a Confederate veteran, had migrated from Kentucky in 1843; his mother was a Georgia native.

After minimal public schooling, J. Marion Futrell (apparently, he preferred to drop the Junius, and one public record even rendered the “J” as James) received an appointment to attend Arkansas Industrial University (now the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) in 1892–93. After his sophomore year, he taught school in Greene, Independence, and Craighead counties until 1896. While in Independence County, he married a student, Tera A. Smith., on September 27, 1893.

Returning to Greene County, he was to the Arkansas House of Representatives in 1896. He was reelected in 1900 and 1902. From 1906 to 1910, he served as Greene County circuit clerk and, in 1912, was elected state senator for the district that comprised Greene, Clay, and Craighead counties. His colleagues chose him as Senate president pro tempore, but the resignation of the new governor, Joseph Taylor Robinson, raised the issue of whether the office passed to the former president pro tempore, William Kavaunagh Oldham, or the incoming one (there was no lieutenant governor’s office at the time). Robinson had given his resignation to Oldham, but Attorney General Hal L. Norwood ruled that Futrell was the rightful holder of the office, pending a special election. In anticipation of a state Supreme Court ruling, the two governors divided the State Capitol, with Futrell being governor of the south wing and Oldham of the north wing. A test case was arranged; in Futrell v. Oldham (1913), the state Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, held that Oldham’s rule ended when his term expired, and thus the office passed to Futrell. In a special election on July 23, 1913, George Washington Hays defeated three other candidates and became the twenty-fourth governor.

Futrell retained his Senate seat. He was active on the Arkansas Council of Defense, a body charged by the federal government with supporting the World War I effort. In 1918, he was a member of the constitutional convention that drafted a new state document. All members of that body signed it, but it was defeated at the polls, in part due to an influenza epidemic reducing turnout.

Futrell had been admitted to the state bar in 1913, and he practiced in Paragould (Greene County) until his appointment in 1922 to succeed Samuel Valdora Neely in the Second Division of the Second Circuit Court. Neeley previously had been appointed to fill the unexpired term of John Frank Gautney. In 1923, Futrell moved to the Twelfth Chancery Circuit, where he remained until elected governor. While chancery judge, Futrell ran for chief justice in 1926 but lost to Jesse Cleveland Hart. After his term as governor ended, he unsuccessfully sought that office again in 1940.

Futrell ran for governor in the Democratic primary in 1932 against Dwight H. Blackwood of Mississippi County. Blackwood was associated in the public mind with the scandals in the state’s multimillion-dollar highway program that had left Arkansas largely in debt to bondholders at a time when cotton was selling for less than the cost of production. Futrell ran as a fiscal conservative and, after defeating Blackwood, easily bested his Republican opponent.

Faced with a technically insolvent state, Futrell came out for scrapping or cutting state programs. High among his objectives was ending state aid to high schools that he considered useless, in part because he considered their graduates not thoroughly educated and because he felt that few educated people were needed in Arkansas. Unemployment, he thought, could be dealt with by eliminating machines. Both conservativism and Greene County patronage went into his firing of the longtime head of the state health department, Charles Willis Garrison. Futrell appointed William Bandy Grayson of Greene County, a former railroad surgeon who opposed immunization and other “socialist” programs. While Futrell was cutting jobs and programs, an estimated 30,000 office-seekers besieged him night and day in his office, at his home, and even by automobile.

Futrell cut expenditures by 51.6 percent. He also supported the Nineteenth Amendment to the state constitution, which mandated a three-fourths majority to raise any then existing state tax; the future sales tax was not covered. The amendment impacted the recently adopted state income tax and the state’s low severance taxes. He also endorsed the Twentieth Amendment, which required a vote of the people on any future state bond issue. Neither amendment solved the problem. When the state could not pay bondholders on schedule, Arkansas became technically bankrupt. Fortunately for Futrell, the federal government’s New Deal programs made up much of the difference. This was especially true in public education. Over much of the state, schools either closed or, in violation of the constitution, districts started charging tuition (which resulted in one noteworthy court case, Burrow v. Pocahontas School District). Although the state did little to combat the effects of the Depression except offer tax relief, the federal government stepped in through such programs as the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). Futrell, although philosophically opposed to public assistance, nevertheless fought vigorous patronage wars to ensure his say in federal appointments in Arkansas.

By 1934, federal officials believed Arkansas was not doing enough. Harry Hopkins, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) director, gave Arkansas until March 1, 1935, to provide $1.5 million to match federal assistance in dealing with poverty. The General Assembly got little assistance from Futrell in trying to meet the deadline, and after the regular session ended on March 14, Hopkins suspended all federal programs, thereby terminating paychecks for 400,000 people. While some in the legislature appeared not to care, Futrell at least grasped the significance of the crisis. After he warned that “we are sitting on powder keg,” he and the legislature got serious.

The only proposals to raise money the governor supported were repealing state prohibition laws and legalizing gambling; the Twenty-first Amendment to the U.S. Constitution had already repealed the Eighteenth Amendment and returned the issue to the states. In reality, Arkansas was already “wet” in untaxed moonshine, and the illegal (and untaxed except locally) gambling of Hot Springs (Garland County) was legendary nationwide. Futrell’s main contribution to the debate was his promotion of the “Convict Corn Plan,” which sought to turn the state penitentiaries into distilleries. In what amounted to a compromise, Futrell supported ending state prohibition in return for the legislature creating the Department of State Police, thus providing the first law enforcement body nominally free from county control. On gambling, Futrell wanted only parimutuel betting on the horses at Hot Springs, but the legislature added the dogs of West Memphis (Crittenden County).

The most important money raiser was a new tax—the sales tax. The first law was poorly written. After a chancery judge declared it unconstitutional, the state Supreme Court sustained it, but significant rewriting took place. This two-percent tax satisfied Hopkins, who then restored federal money. Much of the funds went to the new Arkansas Department of Public Welfare, charged with looking after those who because of age (very young and very old) or illness could not work. A new federal safety net program called Social Security was initiated at the time, financed by worker and employer contributions. Its impact in Arkansas was relatively minor because agricultural workers and domestics were not covered. State payments (“welfare”) now replaced the old poor houses, and some counties turned the former poor houses into nursing homes.

Meanwhile, in eastern Arkansas, the displacement of hundreds of sharecroppers, often by planters who wanted to pocket the federal subsidies they were supposed to give their tenants, prompted a farm revolt under the banner of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union (STFU). Headquartered first in Tyronza (Poinsett County), the union staged strikes that garnered national attention. Perennial Socialist Party presidential candidate Norman Thomas turned up in Marked Tree (Poinsett County) and Birdsong (Mississippi County), where white mobs attacked him. Futrell was unsympathetic, blaming the unemployed for their unemployment. His private opinion, that the poor “were not worth the powder and lead it would take to blow out their brains,” carried over into his views on race. After some African Americans enthusiastically joined the integrated STFU, Futrell told them, “You had better listen to the white folks who have always been your best friends.…There are people who will get you into trouble if you listen to them.” Although Futrell and Senator Joe T. Robinson differed on patronage, they agreed that tenant farmers were basically subhuman, that federal authorities should be kept from investigating Arkansas conditions, and that reports about such conditions should be suppressed.

In response to the national attention on Arkansas, Futrell appointed a state commission to investigate tenancy, but it was left to the federal government to make tentative steps in this area. The Dyess resettlement community in Mississippi County became a prototype for “Uncle Sam’s Farmers.” Ironically, after leaving office, Futrell served as the Dyess community’s attorney. Although the subsequent federal agency, the Farm Security Administration, was eliminated by conservatives during World War II, the resettlement communities made a major impact on Arkansas during a crucial ten-year period.

Futrell garnered a little more success with the Highway Refunding Act of 1934. But his successors—starting with Carl Bailey in 1938—found their hands tied in trying to make state government return to an activist agenda. After his failure to win a Supreme Court seat in 1940, he largely retired. On July 4, 1948, he suffered a severe stroke, and he died on June 20, 1955. Two sons and four daughters survived him.

For additional information:

De Boer, Marvin E., ed. Dreams of Power and the Power of Dreams: The Inaugural Addresses of the Governors of Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1988.

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard B. Gatewood Jr., and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. 2d ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Holley, Donald. Uncle Sam’s Farmers: The New Deal Communities in the Lower Mississippi Valley. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1975.

Johnson, Ben F. Arkansas in Modern America since 1930. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2019.

Junius Marion Futrell Papers. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Lindsey, Michael G. “Localism and the Creation of a State Police.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 64 (Winter 2005): 353–380.

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

The most important legislation passed during Governor Futrell’s administration was that the state could not operate on a deficit budget. Since that legislation, the state has operated in the black.