calsfoundation@cals.org

Poorhouses

aka: Poor Farms

The use of the poorhouse came to the United States during the nineteenth century and was based on a model used in England during the Industrial Revolution. A poorhouse was meant to be a place to which people could be sent if they were not able to support themselves financially. It was believed that these institutions would be a cheaper alternative to the “outdoor relief” (relief requested from a community) that a community sometimes provided. Although this may not have been the case, the poorhouse was a significant institution in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, providing relief to the poor prior to the establishment of welfare systems.

The aiding of a pauper by another person in the community was not unheard of prior to the establishment of poorhouses. Many areas provided outdoor relief to paupers that was normally administered by an Overseer of the Poor, who was often a local elected official. Usually a budget of tax money was set aside to help the poor by providing food, clothing, or even medical treatment when family members, friends, or church congregations could not provide enough aid. However, other methods of supporting the poor were sometimes employed, including contracting with a person in the community to care for a group of paupers or auctioning off the poor, which allowed the lowest bidder to use the pauper’s labor for free for a specified period of time in exchange for food, clothing, housing, and healthcare.

In Arkansas, several counties had programs in place to care for their poor prior to the establishment of a poor farm. In Benton County, for example, one 1861 entry in the court records declared John W. Phleming a pauper and ordered the sheriff to auction him to the lowest bidder on April 16, 1861, for a twelve-month term of service. Cleburne County also had a special fund that aided paupers prior to the establishment of the county’s poor farm. Between 1891 and 1895, Cleburne County spent, on average, approximately $860 each year to aid the county’s poor.

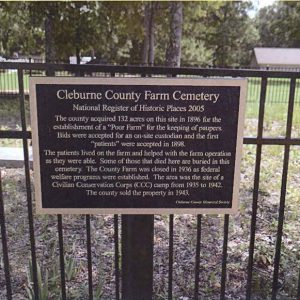

By the second half of the nineteenth century, the poorhouse system came to the United States from England, and poorhouses were built with great optimism. It was hoped that they would be cheaper and more efficient and also aid in the reformation of paupers, eliminating the bad habits and character defects that many people assumed were the causes of their poverty. Although this was not always the case, the poorhouse system was an improvement over previous methods used to aid the poor. Benton County appears to have been one of the first counties in Arkansas to establish a poorhouse, having one in operation by 1858, while others, such as Cleburne and Carroll counties, did not establish theirs until the late 1800s. Pope County opened its first poor farm in 1876 (although provisions were in place to care for paupers as early as 1868). That farm closed in 1885, and Pope County opened a second poor farm in 1899.

Even though many places saw poorhouses as the answer to the problems of aiding the poor, apparently not all counties in Arkansas had poorhouses by the early twentieth century. Clay County, for example, did not establish and build a poor farm until 1912. A special report on paupers in almshouses done in 1904 by the Department of Commerce and Labor, Bureau of the Census, gave an outline of the laws governing poor relief in each state. Regarding Arkansas, it said:

Every county must relieve its own poor. Sheriffs, coroners, constables, and justices of the peace shall give information to their respective county courts of the poor and the county court has the duty of providing for such persons. If satisfied that the applicants are paupers the county court shall order their commitment to the poorhouse, there to remain until discharged by an order of the court. County courts have the power to establish poorhouses, and when completed the court shall let them out annually to the lowest responsible bidder under bond for the faithful care of the inmates. In counties without poorhouses, the court may let the care of the poor to the lowest responsible bidder. The county is not liable for the support of any pauper who refuses to accept county aid in the manner provided above. The county court may cause the employment of each able-bodied pauper on work for the county.

Although the poor farms were necessary in many Arkansas counties in the first part of the twentieth century, the need for them dropped off beginning in the 1930s. Cleburne County, for example, began receiving funding from federal welfare and aid programs, and a welfare committee screened applicants for federal aid. After the main house burned in 1936, the farm closed, and the two “patients” went to live with relatives or were relocated to the Arkansas State Hospital. Carroll and Pope counties also closed their poor farms in the 1930s, although Clay County’s home remained open until 1954, when Arkansas established a managed healthcare system for those in need.

As of 2008, the physical remains of county poor farms are few. In most cases, the cemetery, if the farm had one, is the only surviving element, although a dormitory from the Pope County Poor Farm survives east of Russellville (Pope County) on Tyler Road. The cemeteries usually have plain, unengraved fieldstone markers or no markers at all. (Clay County’s cemetery had wooden markers that have all disappeared.) However, the remaining buildings and cemeteries are important reminders of Arkansas’s efforts to aid its less fortunate citizens.

For additional information:

Arkansas Poor Farm Collection. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

“Benton County Poor Farm Cemetery.” National Register of Historic Places registration form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas. Online at https://www.arkansasheritage.com/docs/default-source/national-registry/be3149-pdf.pdf?sfvrsn=22f75c29_0 (accessed February 7, 2026).

“Carroll County Poor Farm Cemetery.” National Register of Historic Places registration form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Craig, Robert D. “Jackson County Poor House.” Stream of History 49 (September 2016): 3–14.

“The Forgotten of Pope County.” Four-part series. Pope County Historical Association Quarterly 35 (December 2001) and 36 (March, June, and September 2002).

Hidy, Linda Earnheart. “Independence County’s Poor Farm and Cemetery.” Independence County Chronicle 64 (January 2023): 2–22.

National Register nomination forms for Benton, Carroll, Clay, and Cleburne County poor farm cemeteries. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Shull, Laura L. “Pope County’s Pauper Problem.” Pope County Historical Association Quarterly 32 (December 1998): 4–22.

Ralph S. Wilcox

Arkansas Historic Preservation Program

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.