calsfoundation@cals.org

Independence County

| Region: | Northeast |

| County Seat: | Batesville |

| Established: | October 20, 1820 |

| Parent County: | Lawrence |

| Population: | 37,938 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 763.71 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

2,031 |

3,669 |

7,767 |

14,307 |

14,566 |

18,086 |

21,961 |

22,557 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

24,776 |

23,976 |

24,225 |

25,643 |

23,488 |

20,048 |

22,723 |

30,147 |

31,192 |

32,233 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

36,647 |

37,938 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

32,108 |

84.6% |

| African American |

849 |

2.2% |

| American Indian |

243 |

0.6% |

| Asian |

345 |

0.9% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

33 |

0.1% |

| Some Other Race |

1,934 |

5.1% |

| Two or More Races |

2,426 |

6.4% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

3,258 |

8.6% |

| Population Density |

49.7 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$44,319 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$23,733 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

16.7% |

|

Independence County, one of the “mother counties” of the state of Arkansas, originally contained all or part of fifteen modern counties of the state. The county’s history is tied closely to its strategic location—it sits astride the White River where it flows from the Ozark upland into the Mississippi Alluvial Plain; the river bisects the modern county from west to east, and the original Southwest Trail crossed it from northeast to southwest along the Ozark escarpment. Independence County was a dominant cultural force in Arkansas from its beginning through the nineteenth century.

Pre-European Exploration

The White River, which lies between the Arkansas and Missouri Rivers, is one of two major drainages of the Ozarks region. That crucial geographic trait made the Independence County area, with the White River as its original western boundary, unusually rich in archaeological sites. For ten millennia or more, Native Americans lived in the area, and sites from all early cultural periods are numerous. In modern Independence County alone, more than 1,200 archaeological sites have been recorded by the Arkansas Archeological Survey. At the beginning of the twentieth century, archaeologist Clarence B. Moore excavated several sites, including Little Turkey Hill, near the Black River, which forms the eastern boundary of the county.

Although some town sites with mounds were located farther up the river valley, no mound sites were recorded for the modern county area. Nonetheless, the current name for the Mississippian-era (approximately AD 900–1600) archaeological manifestation in the White River valley is the Greenbrier Phase, named for a large town site on the river near Batesville.

European Exploration and Settlement

In recent years, the route of Hernando de Soto and his Spanish army’s expedition through the Southeast (1539–1542) has been re-charted by scholars, and Independence County is on the newly mapped path. The sizeable Indian town of Coligua is now thought to have been on the White River somewhere near Batesville, the last western destination point across the Mississippi Valley before the Spaniards turned south, heading for the Arkansas River Valley.

When European observers returned to the area in the 1700s, the White River valley was no longer inhabited. The fate and ethnic identity of the descendants of the sixteenth century inhabitants are unknown. Instead, the new European visitors found the southeastern Ozarks used by the Osage as a hunting ground, although the tribe lived to the northwest. The valley became one of the stages on which the Osage met the French traders and trappers, as the fur trade flourished in the eighteenth century. The traders were largely from French centers at Kaskaskia and Arkansas Post (Arkansas County), and their presence in the White River valley left French names on the land, such as Poke (or Polk) Bayou, the location of the future county seat, Batesville. The Spanish period brought little change to the fur industry of the area, but it did leave at least one name, Salado Creek, on the Independence County landscape.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

Soon after the Louisiana Purchase, the U.S. government factor at Arkansas Post attempted to establish a trading post at the junction of the Black and White rivers, but it was short lived. The site later became the town of Newport (Jackson County). In 1814, the settlement at Poke Bayou became the location of John C. Luttig, agent of one of the fur-trading firms in St. Louis, Missouri, but his death in 1815 brought the endeavor to a halt.

Missouri Territory established Lawrence County in 1815, a huge area that encompassed most of what became north Arkansas. In an attempt to create a county seat in a townless county, the government established the new town of Davidsonville, but it was located on the Black River, an awkward distance from the increasing population in the White River drainage. When Arkansas Territory was separated out of Missouri Territory in 1819, the new territorial assembly at Arkansas Post rapidly moved to create new counties. One of them was Independence County, created in 1820 by dividing Lawrence County along the watershed between the Black and White river valleys.

The new county would have been extremely large if it had contained all the acreage in the old Lawrence County west of the dividing line. An important national political event drastically reduced the amount of available land, however. The Treaty of 1817 made the White River in the Ozarks the northeastern boundary of the new Cherokee Nation, thus giving a great part of Lawrence County to Cherokee from the Appalachians, groups of whom had already moved west to settle in the Ozarks during the years after 1795. Although the treaty was rejected by the Eastern Cherokee, thousands more moved to Arkansas after 1817, and the United States removed American settlers from the west bank of the White River. The river became the western boundary of Independence County in 1820, making the new county a large stretch of land from the Missouri border south along the east bank of the White River. Other counties were soon formed from the original—Izard in 1825, Jackson in 1828, and others through the century. Independence County did not reach its modern dimensions until Cleburne was created in 1883.

As conflicts between the Osage and Cherokee increased, the Cherokee invited other remnant tribes east of the Mississippi to join them on their Ozark land in order to increase their security. Groups of Shawnee, Delaware, Miami, Piankeshaw, and others responded to the invitation, and Independence County became an international border zone. The Cherokee traded the land back to the United States in 1828 and moved west, but the intermittent conflicts continued in Indian Territory beyond Arkansas. In 1832, the county again became involved in Indian affairs when President Jackson appointed Jesse Bean captain of a newly formed cavalry company charged with patrolling the western country to keep the peace. “Bean’s Rangers” was comprised largely of Independence County men, who found themselves immortalized in Washington Irving’s A Tour on the Prairies.

In the next few decades, the county provided two governors, Thomas Drew and William Reed Miller. Independence County also provided two companies of infantry to the United States Army for the invasion of Mexico in 1847. One of the two county men killed at Buena Vista was Andrew Porter, a local newspaper editor; a large monument was raised to him in Batesville.

Civil War through Reconstruction

The county was represented by three men at the 1861 Secession Convention: M. S. Kennard, Urban Fort, and F. W. Desha. Desha was a known slave owner, with fourteen people held in bondage. Slavery, while an important part of the economy of the county, was not as widespread as in counties to the east and south. The 1860 federal census for Independence County reported a free population of 12,970, with 1,337 enslaved people. This made Independence County the second-most-populous county in the state, trailing only Washington County.

When the Civil War broke out, the county found itself divided in political sympathies; by war’s end, twenty-eight companies had been raised locally—twenty-three Confederate and five Union. Saltpeter mined in the county was used for munitions. The strategic location of the county along the White River brought military occupation, and Batesville and the floodplain became a bivouac for five campaigns during the war, two by Union forces and three by Confederates.

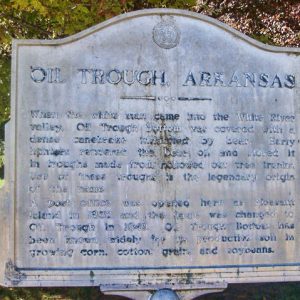

Multiple military engagements took place in the county. The Federal Army of the Southwest occupied Batesville after its victory at the Battle of Pea Ridge in March 1862. The occupation led to the May 3, 1862, Skirmish at Batesville. Other skirmishes were fought again at Batesville, Oil Trough Bottom, Cross-Roads, and Waugh’s Farm. At the end of the war, Independence County, like so much of the Ozark area, had been ravaged by jayhawkers and armies, and it was destitute and depleted of food.

As the local economy struggled to recover, the county provided leadership for both sides during Reconstruction. After the assassination of a Federal registrar in Fulton County in 1868, local leadership of the Ku Klux Klan convened an army at Oil Trough to march on Little Rock (Pulaski County), but the threat was solved by negotiation. When Elisha Baxter, a resident of Independence County, won the governorship after the Brooks-Baxter War in 1872, a political accommodation was reached, and Arkansas focused on domestic reconstruction.

Post-Reconstruction through Modern Era

The county moved into the modern era with an economy based on agriculture, timber, and timber products such as railroad ties, wheel hubs, excelsior, and staves. The mercantile sector was aided by steamboat transportation through the nineteenth century. A series of three locks and dams in the county at the beginning of the twentieth century resulted in the blocking of the river to commercial traffic as the steamboats were replaced by railroads. Batesville continued to be the mercantile center of the county, and the post-bellum decades saw the creation of large, locally owned stores and banks. In the early years of the twentieth century, there were brief economic experiments with shell, pearls, and manganese, but the major additions were the cattle and poultry industries.

With the founding of Arkansas College in Batesville in 1872, the county added higher education to its economic endeavors. Earlier efforts to create permanent institutions of higher education in the county failed, with the Soulesbury Institute operating for several years in the 1850s and Makemie College never beginning operations. Arkansas Normal College operated for several years at the end of the nineteenth century in Jamestown but closed after it was discovered the president sold diplomas through the school correspondence department. There are two colleges in the county in the twenty-first century—Arkansas College became Lyon College, and the Gateway Vo-Tech School became the University of Arkansas Community College at Batesville.

The largest non-manufacturing institution at present is the White River Health System, which has made Batesville an important medical center for the region. Small specialized industries such as GDX Automotive (rubber), White Rodgers (thermostats), Arkansas Eastman (chemicals), and Pro Dentec (dental products) illustrate the county’s modern economic diversity. The fame of National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR) driver Mark Martin helped produce a tourist emphasis on racing, with a new track at Locust Grove. Batesville, still the county seat, remains the largest town. Other communities in the county include Newark, Pleasant Plains, Moorefield, Magness, and Cushman.

For additional information:

Britton, Nancy, ed. Independence County Pioneers. 2 vols. Batesville, AR: Independence Pioneers Committee, 1986, 1989.

Independence County Chronicle. Batesville, AR: Independence County Historical Society (1959–).

James, Nola A. “The Civil War Years in Independence County.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 28 (Autumn 1969): 234–274.

McGinnis, A. C. “A History of Independence County, Ark.” Special issue. Independence County Chronicle 17 (April 1976).

Old Independence Regional Museum. Batesville, Arkansas.

George E. Lankford

Batesville, Arkansas

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Henderson State University

Gold Mine Springs Mines

Gold Mine Springs Mines Arkansas Sheriffs' Youth Ranch

Arkansas Sheriffs' Youth Ranch  Batesville 1915 Flood

Batesville 1915 Flood  Batesville Lime Mill

Batesville Lime Mill  Foushee Cave Snail

Foushee Cave Snail  Garrott House

Garrott House  Independence County Courthouse

Independence County Courthouse  Independence County Map

Independence County Map  Moore Motor Company

Moore Motor Company  Newark Street Scene

Newark Street Scene  Oil Trough

Oil Trough  Oil Trough Sign

Oil Trough Sign  Oil Trough Cotton Gin

Oil Trough Cotton Gin  Old Independence Regional Museum

Old Independence Regional Museum  Ringgold House

Ringgold House  Shadden Springs School

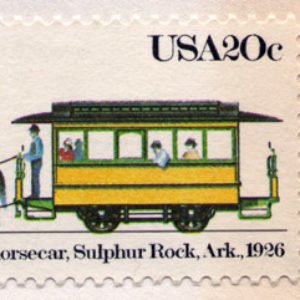

Shadden Springs School  Sulphur Rock Street Car

Sulphur Rock Street Car  Sulphur Rock Streetcar Stamp

Sulphur Rock Streetcar Stamp

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.