calsfoundation@cals.org

Constitutional Conventions

A constitutional convention is a meeting of delegates to establish a document that serves as the framework for government. Arkansas has had eight conventions. Five conventions resulted in documents being adopted, and three conventions produced documents that were rejected by voters. Arkansas has had at least three failed convention calls.

In October 1835, Arkansas’s Territorial Assembly met in Little Rock (Pulaski County) to take steps toward statehood. Legislation calling for a convention was introduced, and the issue of delegate apportionment was raised. An amendment was adopted that provided that convention representation be based on that of the legislature, whose makeup was based upon the number of white men. The legislation called for a convention consisting of fifty-two delegates to be elected in December 1835 and to meet in Little Rock the first Monday in January 1836.

Territorial Governor William Fulton, believing no convention was necessary at the time, allowed the legislation to become law without his signature, stating that he would attempt to carry out the wishes of the people in having a “peaceable assembly.” U.S. attorney general Benjamin Franklin Butler, in a rambling opinion, concurred with Governor Fulton that the convention was unnecessary but was not prepared to state that it was unlawful.

The convention began on January 4, 1836, at the Baptist Meeting House in Little Rock. The first few days were spent organizing, establishing committees, and selecting officers. Selection of a convention printer pitted two outsized personalities, Albert Pike and William E. Woodruff, against one another. Pike was selected, and Woodruff remained embittered long afterward.

Apportionment is a common problem for most conventions whether it be apportionment of convention delegates before a convention or in legislative apportionment while drafting the Legislative Article, or both. Noted author Charles Fenton Mercer Noland recounted that there was a great danger that the convention would break up in a “row” over the topic of legislative apportionment, stating, “There was great excitement. Southern and Eastern members got as hot as pepper-pods.”

Delegates adopted a constitution that was, as author Kay Goss has observed, “very brief, flexible, and more nearly modeled after the U.S. Constitution than were later Arkansas constitutions.” Slavery became part of the adopted constitution. The Arkansas General Assembly denied power to emancipate slaves without owner consent, but it did authorize power “to prevent slaves from being brought to this State as merchandise, and also to oblige owners of slaves to treat them with humanity.”

Nominations to take the constitution to Washington DC for congressional approval resulted in seven nominations and required seven ballots. Noland, another outsized personality, was selected. With the work of the convention completed, it adjourned sine die (that is, indefinitely) on January 30, 1836.

The 1850s brought editorial references in the newspapers about the need for constitutional reform. Eligible voters, though, rejected a convention call in 1853. Also, as early as 1850, U.S. senator Robert Ward Johnson was forewarning that the issues of slavery and secession would have to be confronted at some time, and by 1861 citizen meetings about secession were being held throughout Arkansas. In March 1861, a vote was held to determine whether a secession convention should be convened and to gauge popular opinion on the topic. A majority of voters chose to hold a secession convention and favored secession. There was less voter enthusiasm on the question of actual secession, though. That level of enthusiasm changed with the firing on Fort Sumter, South Carolina, in April 1861, and the convention passed an ordinance of secession. The Arkansas Gazette referenced the need to change the constitution by stating, “Now that Arkansas is out of the Union, now that the old fabric of her government has been torn down, it devolves upon the convention to construct another in its stead.”

The secession convention served as the constitutional convention and adopted a constitution that, for the most part, mirrored the 1836 constitution. One necessary change secession required was that the words “United States of America” be deleted and “Confederate States” added. The convention also changed the slavery provision to an outright and complete ban on the assembly power to pass laws emancipating slaves.

As the state capital of Little Rock fell to the Union in 1863, it became clear that Arkansas would have to look toward re-entering the Union after the Civil War. The terms of Presidential War Time Reconstruction were generous, offering amnesty, and Arkansas quickly met the requirements, thus necessitating a new constitution. Forty-five delegates were selected for the convention representing twenty-four of fifty-seven counties. Northern counties were over-represented at the convention to the exclusion of most other counties. This engendered considerable antipathy and questioning of delegate credentials in other areas of the state.

The 1864 convention nullified actions of the secession convention and declared that the 1861 constitution “is not now, and never has been, binding and obligatory upon the people.” Further, it crafted an article that provided for the abolishment of slavery. Put to voters in March 1864, it was approved by ninety-eight percent of the voters. Suspicions of fraud abounded, but the election was loosely administered by the Union military, and no real action was taken to contest the election.

Congressional/Military Reconstruction after the war was a much stricter prospect than Presidential Reconstruction had been. Military districts, with officers overseeing them, were established, and new constitutions were required for the states of the former Confederacy. In an election, again controlled by the military, a convention call was overwhelmingly favored by voters. The editor of the Arkansas Gazette called it an “illegal body spawned by force and fraud.” He went on to forecast that the “proceedings will be a solemn farce.”

Credentials were administered by the military commander, with convention proceedings starting in January 1868. Race became the dominant issue in the convention. The required provision providing for enfranchisement of African-American males stirred resentment of disenfranchised ex-Confederates, as had the eight African-American men who had been selected as delegates. Those with Union sympathies had an overwhelming majority in the body and adopted an authoritarian document giving state government, and the governor particularly, unprecedented powers. Voters approved the adoption of the constitution in a campaign filled with allegations of fraud and abuse.

Abuse of power by officials, along with the need for re-enfranchisement of Confederate veterans, paved the path for the fifth convention in 1874. Frustrated voters approved a convention call overwhelmingly, and once again cries of fraud abounded. Once the convention convened in July, it proceeded congenially despite a heat wave. It adjourned after fifty-six days and produced a detailed and restrictive document that reflected wariness toward government. This 1874 constitution is the one that remains in effect.

In the 1880s, at least two bills to allow convention calls to be submitted to voters failed to pass, and a convention call that was submitted to voters in 1888 failed handily. Repeated calls for a convention, and legislation authorizing such, were unsuccessful until 1917. In his January 10, 1917, inaugural address, Governor Charles Brough proposed a convention, stating that, “Arkansas firmly needs new governmental garments.” Legislation was enacted, calling a convention without submitting the call to voters for approval.

There was little public enthusiasm for a convention. World War I commanded public attention and concern. Convention efforts were plagued with oppressive heat, quorum deficiencies, and, later, an influenza epidemic that put the entire state in quarantine. Some county bar associations and residents adopted resolutions requesting that the governor call a special session of the legislature to repeal the convention act. These calls were rebuffed.

Even before the convention convened, speculation was rampant that the delegates would adjourn sine die even before organizing or, at least, adjourn until the following summer. A journalist noted, “There is a notable absence of excitement that prevails in the hotel lobbies preceding the opening of a session of the legislature.” Determining that they “couldn’t legally adjourn what was never constituted,” the convention convened on November 19, 1917, organized, and then adjourned until July 1918. When the convention reconvened, some critics noted that public enthusiasm remained low. Delegate (and later governor) Thomas C. McRae quipped, “There is little demand for a new constitution except by those who have violated the old one.”

The convention adopted the progressive measure of suffrage for women. The proposal granted women all rights that men had with the exception of compelling jury service, with the sponsor stating that “jury service is unsought, unsavory, and unpleasant for women.” It also adopted a prohibition on alcohol which “forever prohibits manufacture in Arkansas or shipping to Arkansas any liquor” except for that used in modest amounts for religious purposes. A proposal of the unicameral legislature concept was ultimately defeated.

By late July, nerves were frayed and tempers were flaring. The Arkansas Gazette reported: “Some of the members came very near to being personal in their remarks. Charges of ‘gumshoe methods’ were made and denied.” Despite lacking a quorum, the convention took up the attempt to remove belief in a supreme being as a qualification for being a witness, which caused a delegate to state, “Yesterday you took away all the liquor, and now you are taking away the God of our fathers. I object.”

The effects of the influenza epidemic were still being felt at the time of the election. Citizens were encouraged to avoid crowds, church services were canceled, and, while the statewide quarantine had been lifted by the time of the December 14 election, people were still cautious about crowds. In a very light turnout, voters rejected the document proposed, with sixty-one percent voting against it.

The decades following the 1918 convention saw muted but frequent calls for another convention. Any strides toward a convention were frustrated until 1967, when legislation was enacted creating the Constitutional Revision Study Commission. Upon completion of its work, the commission requested that the Arkansas General Assembly and governor authorize a ballot question regarding a convention in the general election of 1968, with the convention to be held in the spring of 1969, and voting on the constitution in 1969. Friction developed among the commission, the Arkansas Legislative Council, the House, and the Senate on the issues of election timing and delegate apportionment. The House acquiesced to the Senate, which preferred the vote on the constitution be held at the general election of 1970. The Senate, which preferred a “rural-oriented apportionment” in delegate selection, acquiesced to the House version of legislation, which based apportionment on population which, it was felt, complied with a federal court ruling that re-apportioned the Arkansas General Assembly and threatened to create litigation for the convention.

Voters narrowly approved the convention call, and the delegates met on January 6 and 7, 1969, to organize. Dr. Robert A. Leflar of the University of Arkansas School of Law was unanimously elected president of the convention. Leflar urged delegates to be practical and said that “they were not expected to write a constitution for Utopia.” Governor Winthrop Rockefeller addressed delegates and noted the weaknesses of the role of governor under the 1874 constitution. In May 1969, the convention convened with 100 delegates and a professional staff. Major issues were the state’s usury limits, the state’s “right to work” status, and voting age. In August, the convention recessed until January to allow delegates to assess the levels of public acceptance of the provisions.

The idea of allowing voters to vote separately on the three controversial issues had been suggested as means of getting popular support for the rest of the document being created. But when the body reconvened, the convention voted overwhelmingly to submit those provisions within the proposed constitution. Despite all efforts and numerous endorsements of the document, voters defeated the proposed constitution in 1970 with over 57 percent of the vote.

By 1974, backers of reform began to organize. Governor-elect David Pryor, long a proponent of constitutional reform, suggested that he would consider a commission to draft a new constitution. He cited expense and the redundancy of another full convention. Legislation was enacted to create a thirty-five-member commission to propose limited changes and to be voted on in December 1975. Twenty-seven of the delegates were to be appointed by the governor and eight by the legislature. The act was challenged in court, with the trial court declaring the act unconstitutional. On appeal, the Supreme Court concurred in a 4–3 ruling.

In an August 1977 special session of the legislature, compromise legislation was enacted calling for a convention and allowing voters to determine timing of the vote on the document produced by the convention. In the 1978 general election, voters selected 100 delegates to the convention and chose the general election of 1980 as the preferred time to decide the fate of any document produced.

The eighth convention met in May 1979, recessed in mid-June to gauge public opinion, and reconvened in June 1980. A poll suggested that only seven percent of the public even knew of the existence of the constitutional convention, which did not presage a positive outcome in the election. Again, the idea of allowing voters to vote separately on specific items such as interest rate control had been suggested. And, as before, the convention voted to submit everything to the voters in one document. Despite all efforts and numerous endorsements of the document, voters defeated the proposed constitution in 1980 by a wide margin, with 62.7 percent of the voters opposing the measure.

The last attempt to call a constitutional convention was in 1995 at the urging of Governor Jim Guy Tucker, who was described as being “convinced Arkansas shouldn’t begin a new century with a reconstruction-era Constitution.” Hearings held by legislators about a convention were poorly attended, but those who did attend were skeptical and vocal. As before, the method of delegate selection and convention process became issues with critics. Thirty-five delegates were to be elected (one per Senate district), and twenty-six lawmakers were to be appointed delegates. Litigation filed in Chancery Court (now Circuit Court) was assigned to Judge Ellen Brantley, who ruled that the election be canceled owing to a faulty legislative emergency clause. A divided Arkansas Supreme Court reversed the trial court ruling in a four-to-three vote. The special election was held on December 12, 1995, and the convention call failed, with eighty percent opposed.

For additional information:

Cahill, Bernadette. “A Bulwark against Equality: The 1868 Constitutional Convention in Little Rock, Arkansas.” Pulaski County Historical Review 67 (Fall 2019): 84–89.

DeBlack, Thomas A. With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861–1874. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

De Boer, Marin E. Dreams of Power and the Power of Dreams: The Inaugural Addresses of the Governors of Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1988.

Goss, Kay Collett. The Arkansas Constitution: A Reference Guide. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1993.

Harris, Rodney. “Arkansas’s Divided Democracy: The Making of the Constitution of 1874.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2017.

Ledbetter, Calvin R., Jr. “The Constitutional Convention of 1917–1918.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 24 (Spring 1975): 3–40.

———. “The Proposed Arkansas Constitution of 1980.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 60 (Spring 2001): 53–74.

Lindsey, Jacob Ethan. “1864 Arkansas Constitutional Convention.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2017.

Nunn, Walter. “The Constitutional Convention of 1874.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 27 (Autumn 1968): 177–204.

———. “Recent State Constitutional History.” Arkansas Gazette, February 10, 1980, p. 1E.

Rosen, Hannah. Terror in the Heart of Freedom: Citizenship, Sexual Violence, and the Meaning of Race in the Postemancipation South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Wes Goodner

Little Rock, Arkansas

Bowen, Thomas Meade

Bowen, Thomas Meade Law

Law Politics and Government

Politics and Government Calvin Bliss

Calvin Bliss  Constitutional Convention President

Constitutional Convention President  Patsy Crum at 1979-80 Constitutional Convention

Patsy Crum at 1979-80 Constitutional Convention  Clint Huey at 1979-80 Constitutional Convention

Clint Huey at 1979-80 Constitutional Convention  Grandison Royston

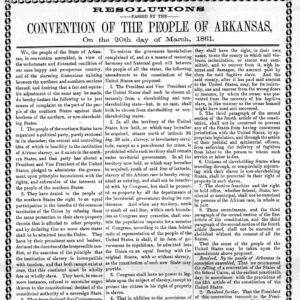

Grandison Royston  Slavery Resolution

Slavery Resolution  David Walker

David Walker

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.