calsfoundation@cals.org

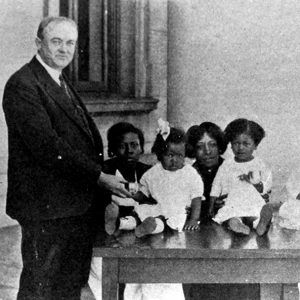

John Ellis Martineau (1873–1937)

Twenty-eighth Governor (1927–1928)

John Ellis Martineau, governor of Arkansas from 1927 to 1928, reflected the emergence of a new style of political leadership in the state. Nominally a Democrat, his administration continued the progressive positions of his predecessors, beginning with George W. Donaghey’s election in 1909. He helped to launch the Arkansas highway system with an innovative change in the source of funding, and he successfully led the relief effort following the disastrous Flood of 1927. His career also advanced a new and more conciliatory position on race relations with his role in the Elaine Massacre and his stance on the 1927 lynching of John Carter in Little Rock (Pulaski County). Overall, his actions as a politician and judge earned him the reputation of a man with managerial skill and personal integrity.

John Martineau was born in Clay County, Missouri, on December 2, 1873, to Sarah Hetty Lamb and Gregory Martineau, a farmer recently arrived from Quebec, Canada. Four years later, they moved to a farm near Concord (Lonoke County), where his parents reared ten children. There, Martineau began a lifelong friendship with the future majority leader of the United States Senate, Joseph Taylor Robinson.

Martineau received his BA in 1896 from the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County). He served as principal of the Chicksaw Male Academy in Tishomingo, Indian Territory. In 1897, he moved to Little Rock to serve as principal of the North Little Rock (Pulaski County) schools and attend the University of Arkansas Law School in Little Rock. He remained principal until 1900, although he received his law degree, was admitted to the Arkansas bar in 1899, and immediately began the practice of law.

In 1902 and 1904, Martineau won election as Pulaski County’s state representative and achieved a leadership role in the Arkansas General Assembly as chairman of the House judiciary committee and a member of the important penitentiary committee. Acting Governor Xenophon Overton Pindall appointed him in 1907 to fill a First Chancery Court vacancy (covering Pulaski, Lonoke, and White counties), and he subsequently won election unopposed to three six-year terms on the bench.

On April 24, 1909, Martineau married Ann H. Mitchell of Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), who died six years later. In 1919, he married the twice-widowed Mabel Erwin Pittman Thomas of Des Arc (Prairie County).

Martineau further advanced his reputation as a progressive politician when, in 1912, Charles Taylor, the mayor of Little Rock, following a national trend, created a vice commission and named Martineau as its chair. The commission recommended ending police toleration of brothels and creating a special police agency to combat prostitution.

As chancery judge, Martineau earned a reputation for fairness and integrity. His role in the 1919 Elaine Massacre in Phillips County also reflected his progressive views on race. Martineau signed a habeas corpus petition blocking the execution of six of the twelve African Americans sentenced for their alleged participation in the riots. Although the Arkansas Supreme Court vacated that order, it gave the defendants time to seek relief in the federal courts and avoid execution. The United States Supreme Court eventually upheld his decision in the case of Moore v. Dempsey.

Martineau first sought the Democratic gubernatorial nomination in 1924, finishing third in a field of five. He entered the race again in 1926. The incumbent, Thomas Jefferson Terral, faced charges of mismanagement when questions were raised regarding the awarding of state contracts and funds for the public roads. Martineau proposed reorganizing Arkansas’s highway system and initiating a road-building program funded by the issue of state bonds. Terral countered that this would mire the state in debt. He further accused Martineau of opposing Prohibition and supporting Sunday baseball. (The repeal of blue laws banning baseball on Sunday was a contentious issue in Arkansas during most of the 1920s). Terral therefore labeled Martineau the candidate of “Booze and Bonds.”

Martineau won a close Democratic primary in August 1926, becoming the first person since Reconstruction to defeat an incumbent Arkansas governor running for a second term. The lack of a competitive second party assured his victory in the November general election.

Martineau became the first governor to broadcast his inaugural address on radio. He restored state honorary boards, ending the system of paid boards created by his predecessor, created the Confederate Pensions Board, and issued bonds to cover the pension program’s cost. His role in two other crises, however, secured his reputation as one of the state’s best governors and brought him to national attention.

The first crisis came with the April 1927 flood of the lower Mississippi Valley. Thirteen percent of Arkansas was flooded. The three worst affected states—Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas—pooled their relief efforts by forming the Tri-State Flood Commission, and Martineau was elected its president. President Calvin Coolidge appointed Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover to head federal relief efforts. Martineau worked closely with Hoover and made several trips to Washington DC to brief President Coolidge.

The second crisis was the May 4, 1927, lynching of John Carter in Little Rock. After the lynching, a mob rioted through a black neighborhood for the next several hours in what the Arkansas Gazette called a “saturnalia of savagery.” Martineau was out of town; when informed by phone that evening of the day’s events, he immediately called out the National Guard and stopped the rioting. He criticized city officials for failing to halt the anarchy and called the tragedy “a deed which will forever remain as a blot upon the fair name of our state.” With reports of the lynching and riot on front pages across the country, Martineau’s decisive handling of mob violence added to his growing national stature.

Martineau’s most lasting gubernatorial program was laying the foundation for the state’s highway system. The state had paid for an earlier road-building program by taxing land through local improvement districts. This caused skyrocketing property taxes and heavy indebtedness for road districts. Martineau proposed that the state assume the districts’ debts and issue highway bonds for road construction. Instead of taxing land to pay the bonds, Martineau urged user-related taxes, such as automobile license fees and gasoline levies. The 1927 Arkansas General Assembly authorized his proposals. These and associated measures, known as the “Martineau Road Plan,” inaugurated Arkansas’s commitment to modern transportation.

Critics repeatedly and unsuccessfully challenged the constitutionality of the plan’s use of bonds in court. Martineau himself ruled on several of the suits, given that on March 2, 1928, only fourteen months after taking office, he resigned as governor to become United States district judge for the Eastern District of Arkansas. Herbert Hoover, who had come to respect Martineau during their collaboration on flood relief, had strongly urged President Coolidge to appoint him. Martineau’s lifelong friend, Senator Joseph Taylor Robinson, had also lobbied hard for him, and the Senate confirmed his appointment on the same day the president announced it. On March 14, 1928, Martineau was sworn in and began his second judicial career. His most noteworthy contribution during his term on the bench was his efforts at reforming the probation system.

After almost nine years on the federal bench, Martineau died of influenza on March 6, 1937. He was buried in Roselawn Memorial Park in Little Rock.

For additional information:

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard B. Gatewood Jr., and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. 2d ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

John Ellis Martineau Papers. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Leon C. Miller

Tulane University

Carl H. Moneyhon

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.