calsfoundation@cals.org

Railroads

In the mid-nineteenth century, the newly created state of Arkansas needed an efficient means of transportation to speed its development. Railroads were constructed in order to get goods to markets elsewhere and to bring in new technologies, as well as people to work in and populate the state.

The construction of railroads had a significant impact on the state, creating towns where none had existed while all but eliminating others due to their lack of ready rail access. Many of the cities and towns in the state were named after prominent railroad executives who influenced, and in some cases were essential to, these communities’ development. While very little passenger service still exists, many of the same routes are used to transport a wide variety of goods throughout the state and beyond.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

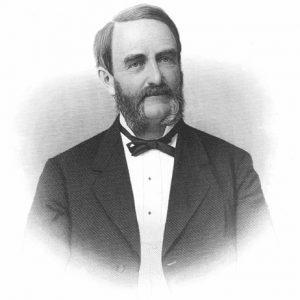

As early as 1835, plans were being made for the construction of railroads in the future state of Arkansas. A group led by Roswell Beebe was planning surveys that had been ordered by the U.S. Department of War for a railroad running from Cairo, Illinois, to Fulton (Hempstead County). These plans eventually resulted in the Cairo and Fulton Railroad, and Beebe became the railroad’s first president.

The Mississippi, Ouachita and Red River Railroad, intended as a connection between the Mississippi River and Dooley’s Ferry on the Red River, was incorporated on August 12, 1852, and is considered the oldest railroad in the state; however, serious construction did not begin on this route until after 1875, and then under another name. The first actual railroad in Arkansas was laid from what is now West Memphis (Crittenden County) to Madison (St. Francis County), which is on the St. Francis River, in 1858. This was the first section of what would become the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad, and it was the only functioning railroad completed by the end of the decade.

During the 1850s, railroad companies were created, sold, and resold due to lack of funding or manipulation of the market. Names changed often, but tracks were planned spanning out from Little Rock (Pulaski County) to Memphis, Tennessee; Fort Smith (Sebastian County); and Helena (Phillips County). Early plans for a line from Little Rock to Helena and to now-defunct Napoleon (Desha County), both on the Mississippi River, were stalled when business interests in Little Rock and Memphis sapped funds intended for these lines instead to build the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad. In retaliation, Masons in Helena withdrew their support of St. Johns’ College in Little Rock.

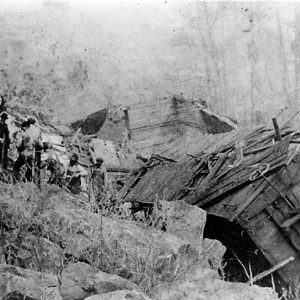

At the end of the decade, many of the plans that were made remained just that—plans—for the next few years. The Civil War was on the horizon, and it not only delayed further construction of railroads, but it also necessitated the rebuilding and repair of what little had already been built.

Civil War through Reconstruction

By the time Arkansas seceded from the Union on May 6, 1861, only the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad’s thirty-eight miles of track from Hopefield (later West Memphis) to Madison were complete and operational. By 1862, the section of the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad from the bank of the Arkansas River opposite Little Rock to DeValls Bluff (Prairie County) on the White River was completed. This was the only significant railroad construction to take place during the war. By 1865, the war had officially ended in the region, although major military operations in the state had ceased some time before.

In 1866, a contract was granted to former Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest and to C. C. McCreanor for the purpose of constructing the final leg of the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad from the White River to the St. Francis River. The camp they established near the St. Francis River for this purpose eventually became the town of Forrest City (St. Francis County), named after the general. This was the first project of many in a resurgence of railroad planning and construction following the war.

In July 1868, Powell Clayton became the new Reconstruction governor of Arkansas. Shortly after taking office, he approved legislation that allowed for the issuance of government-backed bonds for the purpose of financing railroad construction. The bill also provided for the establishment of a railroad commission, which would include on its panel the governor and the secretary of state; no such commission would actually exist, however, for another thirty years.

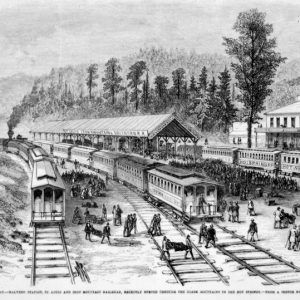

On April 12, 1869, what had been known as the Fort Smith Branch of the Cairo and Fulton Railroad had its charter renewed and became known as the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad. Construction of this line began on March 20, 1869, on the north side of the Arkansas River. A freight yard and depot were also established there, roughly the area of present-day 4th and Poplar streets in downtown North Little Rock (Pulaski County), which was then the unincorporated community of Argenta. On May 28, 1870, the Cairo and Fulton Railroad began construction of its main line at modern-day 11th and Main streets in North Little Rock. With these lines and the Memphis and Little Rock just to the east, the early seeds of a major railroad center in North Little Rock were planted.

By 1871, eighty-six railroads had been chartered in Arkansas, but only 271 miles of track had been completed. The Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad was in financial difficulty. Bonds sold by the railroad to raise funds in 1869 had become almost worthless, and in March 1871, a strike broke out among workers near Ozark (Franklin County) because they had not been paid in several months. By the end of the year, the railroad was taken over by the bondholders, who were intent on salvaging their investment. In response to these and other delays, the Arkansas General Assembly passed legislation mandating that all railroads that had received state aid and were presently under construction should complete one-quarter of their lines within two years and one-half of their lines within three years.

Relieving some of the anxiety that inspired the legislature’s mandate, on August 21, 1871, the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad, advertising service between Memphis and Argenta, was opened. Tracks had been laid for the entire route, but the seventeen miles of track between Brinkley (Monroe County) and DeValls Bluff were not used until a bridge was completed over the White River later in the decade. Until then, connections were made by steamboat or stagecoach from Clarendon (Monroe County) to DeValls Bluff.

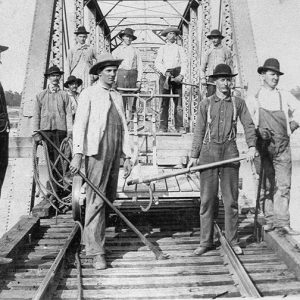

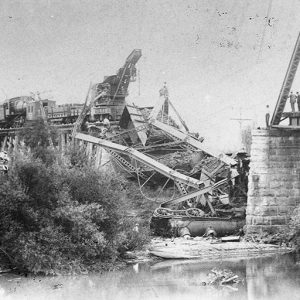

The Cairo and Fulton had been running two separate divisions, one north of the Arkansas River and one south. A ferry was the only means of transferring cargo and passengers from one line to the other, but in 1872, the railroad’s leadership announced the beginning of construction on what would become the Baring Cross Bridge, the first bridge to span the Arkansas River in the area. The bridge was completed on December 21, 1873. Though it washed away in the Flood of 1927, it was rebuilt in 1928. Today, it is still in regular use by both Amtrak and Union Pacific.

The Little Rock and Fort Smith and the Cairo and Fulton railroads were both completed in 1874. By May of that year, 440 miles of track had been laid in Arkansas.

On June 2, 1874, articles of consolidation were filed to combine the St. Louis and Iron Mountain (formerly the Cairo and Fulton of Missouri) and the Cairo and Fulton of Arkansas to create the St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern Railroad. On December 9, 1874, the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad was reorganized as the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railway.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

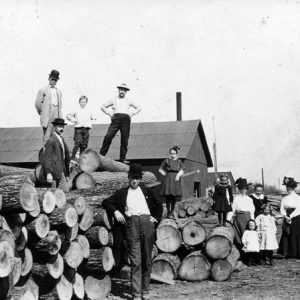

The most significant growth in railroad construction up to that time in Arkansas occurred after Reconstruction. Between 1874 and 1880, the miles of track constructed in the state nearly doubled, from 440 to 859. This expansion continued through the end of the decade and spurred the growth of some industries, such as lumber and mining, while causing a decline in others, such as cotton, due to the influx of cheaper textile goods from the Northeast. After 1880, steamboat travel also experienced declines in favor of railroads’ more flexible form of transporting goods and passengers.

In 1876, James G. Blaine, then speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives and a representative from Maine, sought the Republican nomination for president. His attempt was thwarted, however, when it was discovered that he had acquired Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad bonds and quickly sold them to investors at inflated prices. He was accused of using his position to force the companies to buy the bonds. An investigation into the incident was begun by the House of Representatives but ended upon Blaine’s resignation as representative and appointment by the governor of Maine to the U.S. Senate, an act that removed Blaine from the House’s jurisdiction. The incident is believed to have caused Blaine to lose the Republican nomination for president then and again four years later. When Blaine was finally able to earn the Republican nomination on his third attempt, he was defeated in the general election when reform Republicans supported the Democrat, Grover Cleveland, in the presidential election of 1884.

In 1873, German chancellor Otto Von Bismarck began an anti-Catholic policy known as Kulturkampf, or “culture struggle,” which sparked the emigration of large numbers of German Catholics from the country. German immigrants to the United States initially settled in Pennsylvania and elsewhere in the north and northeast. The Little Rock and Fort Smith Railway began to seek these immigrants as railroad employees by enticing them with land grants and housing. The railroad made a deal with the Diocese of Little Rock to sell land to the immigrants; the railroads were then rich in land after the federal government gave them so much to encourage development. In 1877, a convention of the Southern and Western Immigration Association met in Little Rock to showcase Arkansas as a destination for those immigrants. Shortly afterward, in 1878, the St. Joseph’s Colony was established with land in Conway, Faulkner, and Pope counties along the rail line. The influence of this and other settlements of German and Swiss immigrants can still be seen in industries such as the state’s wine industry. It is evidenced architecturally as well as culturally in the rural Catholic churches that still dot these areas along the Arkansas River Valley, where the line to Fort Smith was built.

While initial rail routes were built with some consideration for access to navigable waterways, the trend after 1880 reflected a decline in the use of steamboats in favor of the more versatile railroads. This had the effect of creating new towns and cities along the rail lines where previously waterway access had been necessary for sustaining them.

New York financier Jay Gould acquired the St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern Railway for $2 million in 1881. In 1882, Gould purchased the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railway, adding it to the St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern Railway to form the largest railroad in Arkansas at the time. Gould’s ownership of the railroad was through the Missouri Pacific, which he had purchased in 1879. Missouri Pacific owned a controlling share of the stock in the Iron Mountain system by 1881 through an exchange of stock, and in another fifteen years, after Gould’s death in 1892, it would retain sole ownership, although the two railroads did not come under the same company name until 1917.

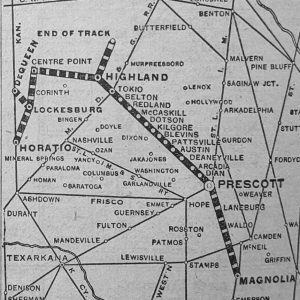

Gould’s competition with the Texas and St. Louis (later the St. Louis and Southwestern Railway) under owner James W. Paramore, a St. Louis cotton buyer, led to Paramore’s building an alternate route from Texarkana (Miller County) to St. Louis via Camden (Ouachita County), Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), Clarendon, and Jonesboro (Craighead County). At a point northeast of Jonesboro, where the tracks from the two railroads intersected, the town of Paragould emerged, which was named by combining the two men’s names. The Texas and St. Louis was created primarily to transport cotton and thus was also known as the Cotton Belt railroad.

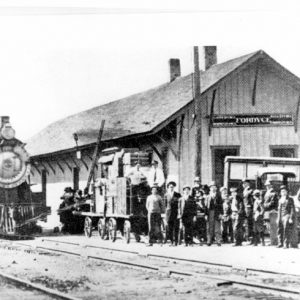

Paramore hired surveyor Samuel W. Fordyce to locate the route of the railroad, and the tracks for the Texas and St. Louis were laid from Gatesville, Texas, to Birds Point, Missouri, by 1883. Fordyce later became the president of the railroad, and the town of Fordyce (Dallas County), as well as the Fordyce Bathhouse, which he built in Hot Springs (Garland County), are named for him.

In Missouri, the Southwest Branch of the Pacific Railroad was acquired by the St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (Frisco) in 1876. The company created the St. Louis, Arkansas, and Texas Railway, which had built 188 miles of track from Monett, Missouri, to Brentwood (Washington County) by 1881 and additional track to Fort Smith by 1882. The presence of the Frisco in northwest Arkansas allowed for the growth of Rogers (Benton County)—named for Captain Charles Warrington Rogers, general manager of the Frisco—from a single cabin in March 1881 to a fully incorporated town by June of the same year. The Frisco route bypassed the older town of Bentonville (Benton County). Because of the railroad, for many years afterward Rogers continued to be the more prosperous of the two cities, even though Bentonville was the county seat. After the Frisco was acquired by Burlington Northern in 1980, these rails became the property of the Arkansas & Missouri Railroad, which began freight operations in 1986 and passenger service in 1990.

The Arkansas Railroad Commission was created in 1899. It was made up of the governor, attorney general, state auditor, secretary of state, state treasurer, commissioner of agriculture, and commissioner of state lands. The commission was charged with overseeing the development and activities of the railroad industry in the state. Its primary task was to set rates on intrastate freight shipments

The first charter issued by the new commission for the construction of a railroad was granted to the St. Louis and North Arkansas Railroad on May 17, 1899, to build the line that would link Eureka Springs to Harrison. The line was completed by 1901, but went out of business in 1906.

Early Twentieth Century

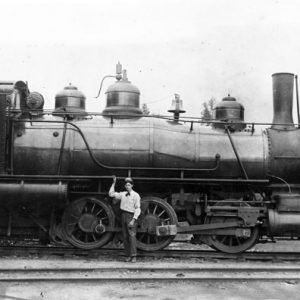

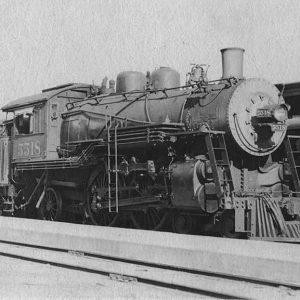

By the end of the nineteenth century, more than 3,360 miles of track were in use in Arkansas. The main routes in the state had been established prior to the turn of the century, but many branch or spur routes were also developed, providing passenger and freight service to towns and cities off the main routes. Many smaller short line or local railroads existed for specific purposes, some only for transporting raw materials from where they were being mined or harvested, others to provide passenger service to a main line or another nearby community. It was during the early part of the twentieth century that railroads would see their peak, particularly for passengers.

In 1898, the Choctaw, Oklahoma, and Gulf Railroad bought the Little Rock and Memphis Railroad, beginning a process of networked railroads which, in 1904 and 1905, came to be dominated by the Chicago, Rock Island, and Pacific Railroad, generally known as the Rock Island line. Until its bankruptcy in March 1980, the Rock Island line was a major player in the Arkansas railroad scene.

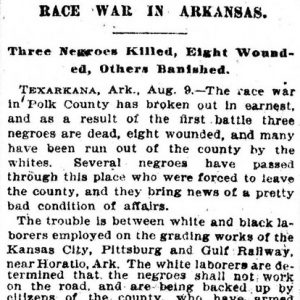

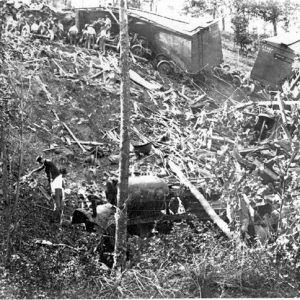

The former St. Louis and North Arkansas Railroad was reorganized on August 4, 1906, into the Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad. Almost immediately, the railroad contracted to begin building tracks that would eventually connect the railroad to Helena, thus providing a connection between Helena and Kansas City, through agreements with other companies owning tracks in Missouri. The railroad made the connection to Helena by 1909, but the project never had financial success. A major blow came on August 5, 1914, when a Missouri and North Arkansas motor car collided with a Kansas City Southern train south of Joplin, Missouri, killing forty-two people. The two railroads split the responsibility for compensating the families involved. Another blow came in December 1917 when the federal government nationalized most railroads during World War I (until 1920) and paid the Missouri and North Arkansas employees based on a flat rate that was being paid across the country. This rate was much greater than that enjoyed by the employees prior to the government takeover, but the company was returned to private control later that year, at which time their pay was returned to its previous level. As a result of the pay reduction, on February 1, 1921, the railroad employees went on strike. The strike attracted national attention and was considered one of the longest railroad strikes in U.S. history, ending in May 1922 after fifteen months and much violence. Other factors, such as the topography of the land and absentee ownership and management of the company, contributed to its struggles and eventual demise.

By 1927, the St. Louis-San Francisco Railway Company (Frisco) operated just over 700 miles of track in Arkansas, with an assessed value of almost $12 million. The Missouri Pacific operated 1,810 miles of track in Arkansas by that year, representing more than thirty-five percent of the state’s total mileage, with an assessed value of almost $39 million. The Rock Island operated 705 miles of track in Arkansas with an assessed value of almost $12 million. The Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad was in receivership by 1927. It was foreclosed upon, sold in 1935 for $350,000, and renamed the Missouri and Arkansas Railway.

The last railroad development in the state was attempted in the late 1920s by the Cotton Belt, with its efforts to create a rail system in the St. Francis River valley. The project was not successful and eventually led to the bankruptcy and sale of the railroad to the Southern Pacific in 1932. (It was in receivership from 1932 to 1947.)

World War II through the Modern Era

By 1941, approximately 4,700 miles of railroad track were in use in Arkansas. Although the railroads remained important to industry and shipping, passenger service began to decline with the increasing popularity of the automobile. In 1956, Congress passed the Federal Aid Highway Act, creating some 41,000 miles of interstate roads, which rapidly became more popular than train travel. Increased activity of commercial airlines also reduced the use of rail passenger service.

Interstates had been built and were now in use across the country. Amtrak was created in 1970 and officially took over most interstate passenger rail service in the United States on May 1, 1971. Smaller mergers and acquisitions from the prior eras now increased as companies continued to adjust to the changing transportation market. Today, of the many larger carriers that crisscrossed the state, the Union Pacific controls the majority of the main routes connecting Arkansas to the rest of the world by rail. The lone remaining connection to national rail passenger service is Amtrak’s Texas Eagle, running from Chicago to Dallas, San Antonio, and eventually Los Angeles, with Arkansas stops in Walnut Ridge (Lawrence County), Little Rock, Malvern (Hot Spring County), Arkadelphia (Clark County), and Texarkana, utilizing Union Pacific track.

Tourist rail developed in the form of the Scott and Bearskin Lake Railroad in Scott (Pulaski and Lonoke Counties), created as an attraction for the then privately owned Plantation Museum there. Robert Dortch, who was responsible for creating the Scott and Bearskin Lake Railroad, died in 1978, and shortly after, his son, Robert Dortch Jr., closed the railroad, moving the steam engine and tracks to Eureka Springs and utilizing the remaining track from the original Eureka Springs Railway to create a passenger service, the Eureka Springs and North Arkansas Railroad, in 1981.

In 1996, the Union Pacific Railroad, which had acquired the Missouri Pacific in 1982, merged with the Southern Pacific (Cotton Belt). With that merger, the main lines that had crisscrossed the state under various company names and logos had now, with minor exception, become one.

Arkansas Department of Transportation statistics for 2005 show twenty-five railroads operating on 2,730 miles of track. Of that number, fifteen are considered local or short line railroads. In 2003, over twenty-four million tons of products originating in Arkansas were transported by rail. These items included non-metallic minerals, primary metal products, glass and stone products, and lumber products, among others. As of 2005, Arkansas’s twenty-five railroads tied for ninth in the nation in the number of railroads operating within a state.

For additional information:

Adams, Walter M. The White River Railway: A History of the White River Division of the Missouri Pacific Railroad Company, 1901–1951. North Little Rock, AR: Walter Adams, 1991.

Arkansas and Missouri Railroad. http://www.arkansasmissouri-rr.com/ (accessed August 16, 2023).

Arkansas Railroader. Little Rock: Arkansas Railroad Club (1969–).

Baker, William D. “Historic Railroad Depots of Arkansas, 1840–1970.” Arkansas Historic Preservation Program.

Bolton, S. Charles. “Missing the Train: Arkansas and the Pacific Railroad, 1848–1862.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 80 (Autumn 2021): 309–352.

Brown, Carl E. “Improving the way to the Land of Opportunity: Internal Improvements in Antebellum Arkansas.” PhD diss., University of Memphis, 2012. Online at https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/etd/549/ (accessed January 2, 2024).

Campbell, Donald Kennedy, II. “A Study of Some Factors Contributing to the Petition for Abandonment by the Missouri and Arkansas Railroad in September, 1946.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 8 (Winter 1949): 267–326.

Clifton Hull Papers. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Dew, Lee A., and Louis Koeppe. “Narrow-Gauge Railroads in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 31 (Autumn 1972): 276–293.

Duckworth, Charles A. Down the Iron Mountain Route: A Pictorial Railroad History through Arkansas. Brookfield, MO: Donning Company Publishers, 2017.

Evanson, Robert. “The Fayetteville & Little Rock Railroad.” Flashback 46 (May 1996): 17–24.

Fair, James R. The Louisiana and Arkansas Railway: The Story of a Regional Line. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1997.

———. The North Arkansas Line: The Story of the Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad. Berkley, CA: Howell-North Books, 1969.

Grant, Roger H. “The Ozark Short Line Railroad: A Failed Dream.” Missouri Historical Review 100 (July 2006): 197–211.

Handley, Lawrence R. “Settlement across Northern Arkansas as Influenced by the Missouri & North Arkansas Railroad.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 33 (Winter 1974): 273–292.

Harlow, Lester C. “A Short History of Railroads in Benton County, Arkansas.” Benton County Pioneer 16 (October 1967): 76–81.

Huff, Leo E. “The Memphis and Little Rock Railroad during the Civil War.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 23 (Autumn 1964): 260–270.

Hull, Clifton E. Railroad Stations and Trains through Arkansas and the Southwest. Hart, MO: Whiteriver Productions, Inc., 1997.

———. Shortline Railroads of Arkansas. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1969.

———. The Dardanelle & Russellville Railroad. Conway: University of Central Arkansas Press, 1995.

“KCS Railroad Special Edition.” Mountain Signal, June 2000.

Kennan, Clara B. “A Railroad Empire Rose and Fell in Benton County.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 13 (Summer 1954): 154–159.

Pollard, Bill. “Railroad Ransom: History of the Searcy Branch of the Rock Island Line Railroad.” White County Heritage 45 (2007): 36–78.

Porter, Rusty. “Railroads of Phillips County.” Phillips County Historical Quarterly 26 (June and September 1988): 1–26.

Scott, Eloise. “Railroads and Strawberries.” White County Heritage 19 (1981): 22–37.

Thompson, George H. “Asa P. Robinson and the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 39 (Spring 1980): 3–20.

Winn, Robert G. Railroads of Northwest Arkansas. Fayetteville, AR: Washington County Historical Society, 1986.

Winters, Charles E. “The Fort Smith & Western Railway.” Journal of the Fort Smith Historical Society 16 (April 1992): 3–21.

Woods, Stephen E. “The Development of Arkansas Railroads, Part I.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 7 (Summer 1948): 103–140.

———. “The Development of Arkansas Railroads, Part II.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 7 (Autumn 1948): 155–193.

Michael Hodge

North Little Rock, Arkansas

My dad, Roy Thomas Parks, was born in Harville, Missouri, and moved to Delaplaine (Greene County) around 1916. He worked as a brakeman for the Missouri-Pacific Railroad Company during World War II. After he quit in the early or mid-1940s, people from St. Louis, Missouri, came to Arkansas and hired him to buy railroad ties. He ran a tie yard at Delaplaine off and on until sometime in the 1960s and also in Knobel (Clay County). He would purchase the ties and had several people who worked every weekday and Saturday for him. They would stack them to cure, and then when the railroad company needed them, he would load boxcars up and ship them to St. Louis. He also was in charge of going to the woods and finding timber standing ready to cut and make ties. He would lease the timber and pay the owners of the timberland. He made the decision what ties would be used and culled the rest, and no one could fool him on the type of timber they used to cut the ties from. A Mr. Frank Gould, whom I believe was from St. Louis, was over him.

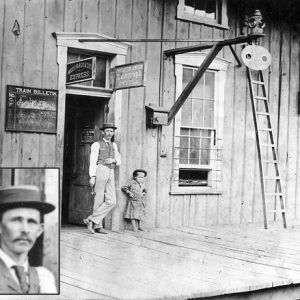

I am a longtime employee of Union Pacific Railroad, but my grandfather by marriage was the frieghtmaster in Hoxie in the 1930s to 1950s. I have an original photo of him in front of the Hoxie depot in 1932 with the entire service unit staff. I went to Hoxie and found the concrete slab–that is all that is left from this photo. My grandfather’s name was Earnest L. Reed.