calsfoundation@cals.org

Bill Clinton (1946–)

aka: William Jefferson Clinton

Fortieth and Forty-second Governor (1979–1981, 1983–1992)

Forty-second President of the United States (1993–2001)

William Jefferson Clinton, a native of Hope (Hempstead County), was the fortieth and forty-second governor of Arkansas and the forty-second president of the United States. Clinton’s tenure as governor of Arkansas, eleven years and eleven months total, was the second longest in the state’s history. Only Orval E. Faubus served longer, with twelve years. Clinton was the second-youngest governor in the state’s history, after John Selden Roane, and the third-youngest person to become president, after Theodore Roosevelt and John Fitzgerald Kennedy.

Clinton’s years as governor were marked by extensive efforts to reform the public school system and to spur economic growth. He persuaded lawmakers to enact numerous educational reforms, levy substantial taxes to improve education, and enact an array of laws to invite industrial development and spur business investment.

His election as president in 1992 was followed by the longest period of sustained economic growth in U.S. history. A controversial package of spending reductions and tax increases early in his first year in office and further budget changes in 1997 led to the elimination of deficits in the federal budget and to four successive budget surpluses. It had been fifty years since the government ran three or more surpluses in a row (1947–1949).

Clinton, a Democrat, was president during a period of intense partisanship. Throughout his political career, he demonstrated an ability to bounce back from defeats and scandal. His presidency was beset by numerous investigations, one of which resulted in his becoming the second American president (and the first elected) to be impeached. Still, he left office in 2001 enjoying high popularity.

Early Life

Bill Clinton was born William Jefferson Blythe IV on August 19, 1946, in Hope, the son of William Jefferson Blythe III and Virginia Cassidy Blythe. His father, a traveling salesman, was killed in an automobile accident before Clinton was born. After he became president, Clinton learned that his father had been married at least three times and that he had a half-brother and a half-sister whom he had never met. He changed his name to Clinton after his mother married Roger Clinton, a car dealer. (The home were Clinton lived the first four years of his life is now the President William Jefferson Clinton Birthplace Home National Historic Site.) The family moved to Hot Springs (Garland County), living in a home on Park Avenue; he graduated from high school in Hot Springs. After he became president of the United States, he and his mother revealed that Roger Clinton had been an alcoholic who abused Clinton, Clinton’s mother, and Clinton’s younger half-brother, Roger.

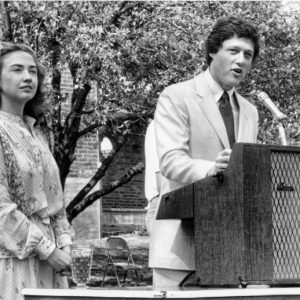

Clinton was a precocious student, musically talented and popular. He graduated from Georgetown University in Washington DC, attended Oxford University in Oxford, England, on a Rhodes Scholarship, and received a law degree from Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, where he met his future wife, Hillary Rodham of Park Ridge, Illinois. After receiving a law degree in 1973, he returned to Arkansas to teach at the law school of the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County). Rodham joined him on the faculty in 1974, and they were married on October 11, 1975. They lived in what is now the Clinton House Museum.

Early Political Career

Intent on a political career since he was a child, Clinton was selected to offices throughout his student career. While a student at Georgetown, he worked on the staff of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, which was chaired by Arkansas senator J. William Fulbright, a Democrat. In 1972, he coordinated the presidential campaign of Senator George S. McGovern in Texas. He also handled the Arkansas delegation at the Democratic National Convention.

In 1974, only months after joining the faculty at the University of Arkansas, he ran for United States representative in the state’s Third Congressional District (northwestern Arkansas). He won the Democratic nomination but lost—fifty-two percent to forty-eight percent—to Representative John Paul Hammerschmidt, a Republican running for his fifth term. Clinton easily won a race for attorney general in 1976 against Democratic opponents George O. Jernigan Jr. and Clarence Cash. He was unopposed in the general election. He gained popularity when his office opposed rate increases for utilities and fought, on environmental grounds, Arkansas Power and Light’s plans to build a coal-fired plant in Independence County to generate electricity. In 1978, he easily defeated four candidates for the Democratic nomination for governor and then just as handily defeated the Republican candidate, Lynn Lowe of Texarkana (Miller County), compiling 63.4 percent of the votes. He was sworn in as governor in January 1979 at the age of thirty-two.

Governor of Arkansas

In his first term, Clinton proposed modest reforms in education and commercial regulation, particularly to control pollution, but his biggest initiative, a highway program, was expensive fiscally and politically. He persuaded the legislature to increase taxes on motor fuels and to raise other fees on vehicles. Increases in the annual registration fees of automobiles and trucks were particularly unpopular. Clinton would always say that the license fees cost him re-election in 1980, although other initiatives he undertook angered large interests. The trucking industry was irked by his efforts to raise taxes on big rigs and also by his opposition to raising the weight limits for Arkansas highways; poultry interests were irked by the highway weight issue, the wood-products industry by his office’s harsh criticism of clear-cutting forests, and bankers by his suggestion that idle state funds be distributed among banks based on their lending policies. Utility interests, which were particularly powerful, were angry over Clinton’s efforts to stiffen the regulation of rate increases, and he also battled the state’s largest electric utility, Arkansas Power and Light, over the parent company’s successful effort to make Arkansas ratepayers bear a large share of the costs of a big nuclear power plant at Port Gibson, Mississippi. Those interests tended to support his Republican opponent in 1980.

Clinton was also hurt politically by the presence of Cuban refugees at Fort Chaffee, sent there by Clinton’s friend, President Jimmy Carter. Cuba had temporarily lifted its exit restrictions and permitted about 125,000 Cubans to go to the United States by boat. Carter sent roughly 25,000 of them to Fort Chaffee. Incidents of rioting and other violence occurred in May and June 1980 inside and outside Fort Chaffee, with sixty-two people injured on June 1, none seriously, and four buildings at the fort set on fire. A video of the rioting Cubans turned up in an effective campaign ad for Clinton’s opponent in the election. Frank D. White, a former banker and state industrial-development official, switched parties to run for governor in 1980. He blamed Clinton for the threat to public safety that the Cubans represented and for higher vehicle license fees. He defeated Clinton in the election with almost fifty-two percent of the vote.

Clinton began practicing law in Little Rock (Pulaski County) and prepared for the 1982 governor’s race. He defeated former Attorney General Joe Purcell and former U.S. Representative Jim Guy Tucker for the Democratic nomination and easily defeated White to regain the office. He was re-elected in 1984, 1986, and 1990 (Arkansas adopted a four-year term for governors starting in 1986).

During the campaign of 1982, Clinton promised to make major strides in education, including a large investment of public money, but he avoided saying he would raise taxes. He was handed the opportunity to raise taxes when the Arkansas Supreme Court in the spring of 1983 ruled that the system of financing the public schools was unconstitutional because it provided unequal resources for school districts. Clinton called a special session of the legislature and proposed higher taxes and a large package of school laws, including a new formula for distributing the state’s dollars among school districts more equitably and a controversial law requiring all teachers and school administrators to pass a test of basic skills. The legislature raised the sales tax from three to four percent and approved most of his other legislation. The Arkansas Board of Education adopted tougher accreditation standards for schools, which were proposed by a study commission headed by the governor’s wife.

The regular legislative session of 1985 was devoted to economic development. The legislature approved almost all of Clinton’s program, which included changes in banking laws, start-up money for technology-oriented businesses, and large tax incentives for Arkansas industries that expanded their production and jobs. Arkansas was one of the best states in new job creation in the next six years, but most of the jobs did not pay high wages, and it remained one of the worst states in average income. The state of prisons also came to a head that same year with an investigation Clinton ordered into plasma extraction from prisoners.

Clinton tried, rather unsuccessfully, in 1987 and 1989 to raise new taxes for education, but after a resounding victory in the 1990 election over a well-financed Republican opponent, Sheffield Nelson, and the defeat of several key legislative opponents, he had major success in 1991. He had called a news conference in 1988 to announce plans to run for president but changed his mind at the last minute, explaining that the campaign and the job would be too hard on his wife and daughter, Chelsea Victoria, who was eight. Although he had promised during the 1990 campaign that he would complete his four-year term, he decided to run for president in 1992. His education reforms and his leadership of several national organizations, including the National Governors’ Conference and the Democratic Leadership Council—a group of moderate Democratic officeholders and businesspeople who sought to alter the liberal bent of the national Democratic Party—strengthened his national stature and gave him important connections.

Presidential Elections

On October 3, 1991, Clinton announced that he would run for president in 1992. He had five Democratic opponents: Senator Robert Kerrey of Nebraska, Senator Tom Harkin of Iowa, former senator Paul Tsongas of Massachusetts, Governor L. Douglas Wilder of Virginia, and former California governor Edmund G. (Jerry) Brown. Although he quickly established himself as the frontrunner, his campaign was nearly derailed by accusations of marital infidelity—including a charge by a Little Rock woman named Gennifer Flowers that she had had a long-running affair with Clinton when he was attorney general and governor—and by revelations that he had taken unusual steps to avoid military service during the Vietnam War. In addition, his ordering the execution of mentally impaired prisoner Rickey Ray Rector sparked controversy. He deflected those controversies and regained momentum. He easily won the Democratic nomination and chose Senator Albert Gore of Tennessee as his vice presidential running mate.

Having successfully led a war against Iraq a year earlier, President George H. W. Bush enjoyed high poll ratings when the campaign began, but a sluggish economy and high unemployment diminished his popularity. Clinton concentrated on the economy, promising to secure health insurance coverage for every American, reform the welfare system, enact a tax cut for the middle class, begin a national service program, reform the system of financing federal campaigns, and invest heavily in the nation’s infrastructure, which he said was deteriorating. H. Ross Perot, a wealthy Texas businessman, ran as an independent and promised to eliminate the federal budget deficit by raising taxes and cutting government spending. Clinton was helped by the weak economy and a perception that President Bush had put little emphasis on improving it, but Clinton also proved a far better campaigner, particularly in the three debates. The contrast between the aging and stiff president and the young and agile governor was especially sharp in the second debate, a town-hall arrangement where Clinton engaged questioners personally. (The campaign was documented extensively for the 1993 film The War Room.) Bush counted on his vast experience in foreign policy and the successful war to liberate Kuwait to give him an edge against the governor of what he described as a small and poor state. He called Clinton a “tax-and-spend liberal.” Clinton received forty-three percent of the popular vote to Bush’s thirty-eight percent and Perot’s nineteen percent and won even more decisively in the Electoral College, 370 to 168.

Although he had been battered by controversy during his first term and his party had lost control of both houses of Congress in 1994, Clinton had an easier election for a second term in 1996. Senator Robert Dole of Kansas, a longtime veteran of Congress and a moderate, won the Republican nomination. Perot ran again, this time as the candidate of the Reform Party, which he organized. Dole attacked Clinton’s character and pointed to his own long service in the military in World War II and in Congress. Dole’s age, seventy-three, was a subtle issue. Clinton was re-elected with forty-nine percent of the popular vote to Dole’s forty-one percent and Perot’s nine percent. Clinton won the electoral vote with 379 votes to Dole’s 159.

Domestic Record

Bitter controversy dogged Clinton from his election until he left office. He had said during his first campaign that he would lift the ban on homosexuals serving in the military, and soon after the election, he indicated that he would move quickly. Protests in Congress and from military leaders dominated the periods before and after his inauguration until he reached a compromise with service leaders: homosexuals could serve if they did not disclose their sexual orientation and did not engage in homosexual conduct. Still, the issue crippled him politically. In his first two years, he did succeed in passing a law that required companies with more than fifty workers to give workers up to twelve weeks of unpaid leave each year to cope with family problems, in addition to another law that established a national service program called AmeriCorps in which young people perform public service work for a period of time.

Two congressional battles in the first two years decided the course of his presidency. Even before he took office, Clinton was persuaded by his new economic team—including Robert E. Rubin (chairman of the National Economic Council), Laura D’Andrea Tyson (chair of the Council of Economic Advisers), Leon Panetta (director of the Office of Management and Budget), Lawrence H. Summers (undersecretary of treasury for international affairs) and Alan S. Blinder (an economic adviser)—that the nation’s critical economic need was to lower the huge federal budget deficit, which had reached $290 billion in President Bush’s last fiscal year (1992–93). Lowering or eliminating the deficit would reassure the bond markets, reduce long-term interest rates, and encourage greater business investment and more jobs. His budget package—which passed both houses of Congress without a vote to spare and without a single Republican vote—reduced spending over five years by $255 billion and increased taxes, mainly on high incomes, by $241 billion. The legislation also expanded the Earned Income Tax Credit, which provided extra income for millions of families earning less than $30,000 a year. The deficit declined sharply over the next two years and disappeared in 1998.

The other congressional battle was over national health insurance. Clinton appointed his wife to chair a task force to study insurance problems and recommend a plan for guaranteeing coverage for everyone. Under that plan, people would join an alliance in each state that would contract with insurance companies and other groups to offer insurance to members. The long, complicated legislation was opposed by many insurance companies and other healthcare groups and by every Republican in Congress. Clinton failed to work out a compromise with moderate Republicans who wanted an expanded insurance system, and the initiative died. That failure and the unpopularity of tax increases cost a number of Democrats their seats in the 1994 congressional elections, and Republicans gained control of the House of Representatives and the Senate, making it difficult for Clinton to get any of his proposals through Congress in his last six years.

After Republicans gained control of Congress, Clinton spent the next six years battling conservatives over the federal budget and social issues such as abortion. The Republican majority, led by the new speaker of the House of Representatives, Newt Gingrich of Georgia, sought to cut federal spending on education, environmental protection, and Medicare and Medicaid. Clinton used his power of veto and the threat of a veto to thwart most of the cuts. Years later, he said halting all the Republican initiatives that he considered so harmful was one of his greatest achievements. When Clinton and the congressional majority could not agree on a budget in 1995 and 1996, the Republicans forced a temporary shutdown of the government. Public opinion seemed to side with the president, and Congress eventually capitulated, which greatly strengthened Clinton’s standing in the presidential election year of 1996.

Despite the stalemate with Republicans on most issues, Clinton succeeded on two major initiatives after 1994. Since 1985, when he was governor, Clinton had advocated a major overhaul of the welfare system to encourage work, and in his 1992 campaign, he had promised to “end welfare as we know it.” When Congress approved a harsher version of his proposal in 1996, he signed it into law over the objections of many in his own administration and in Congress. He had vetoed two earlier measures that were even harsher. The law limited lifetime welfare benefits to five years and required adult recipients to work after two years on welfare. In 1997, he worked out a compromise budget package with Congress that included tax cuts and spending cuts aimed at hastening a balanced budget, which was balanced the next year for the first time since 1969. The legislation also began a new children’s health insurance program, which expanded Medicaid coverage to millions more children from low- and middle-income families. Clinton also signed into law bipartisan measures to combat terrorism, allowing more spending to fight terrorism and making it easier to deport foreigners suspected of terrorism.

Foreign affairs

World communism was no longer the nation’s principal adversary when Clinton took office. Instead, he was confronted with religious and ethnic strife, genocide, and suffering in smaller and weaker countries where the interests of the United States were not clear. He was at first reluctant to commit military forces to such regions, but he developed an expansive view of the country’s strategic interest in protecting human rights and promoting stability. He sent forces to end fighting and protect civilians in Haiti, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Kosovo in the former republic of Yugoslavia. He would later state his regret that he had not done the same in 1994 when two million people were displaced and hundreds of thousands were slain in the African nation of Rwanda.

Clinton tried to arrange peace between religious and ethnic rivals in the Middle East and in Northern Ireland. His intervention brought an end to religious strife in Northern Ireland, a declaration of peace between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization, and an agreement between Israel and Jordan to end their state of war.

In most foreign interventions, he was opposed by leaders of the Republican Party and sometimes, according to polls, by the public. When the Mexican peso collapsed in 1995, threatening the failure of the Mexican economy, Clinton proposed a loan package to Mexico to ease the crisis. Congress balked when polls showed public opposition to the bailout. Clinton then devised a $20 billion loan package to restore world confidence in Mexico and executed it alone. Mexico rallied and paid off the loans with interest in 1997, three years ahead of schedule.

But the major instrument of Clinton’s foreign policy was not military intervention or diplomacy but trade and economic leverage. He believed that lower tariffs and freer trade with other nations would raise the standard of living in poor nations, increase U.S. exports, and improve the American economy. Over the opposition of many in his own party who thought it would cost too many American jobs, he completed negotiations and won ratification in late 1993 of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which reduced tariffs and created a free-trading bloc among the United States, Canada, and Mexico. He also finished work on a comprehensive world trade agreement called the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which Congress ratified in 1994.

Investigations and Impeachment

For his entire presidency, Clinton, his wife, and members of his administration were hounded by accusations of wrongdoing, concerted campaigns to discredit him, as typified by the 1994 Clinton Chronicles video and Richard Mellon Scaife’s so-called Arkansas Project, as well as allegations, advanced by right-wing outlets, that he had personally framed serial rapist and killer Wayne DuMond. When Republicans gained control of the House of Representatives and the Senate after the 1994 elections, congressional committees conducted investigations and lengthy hearings on accusations of misconduct. Also, an unprecedented seven independent counsels (special prosecutors) were appointed to investigate allegations of misconduct. A law enacted during the Watergate scandals relating to the administration of President Richard Nixon provided for the appointment of independent counsels when there were suspicions of misconduct involving the president, vice president, or other major administration officials. Most of the investigations did not involve the president. Allegations included the following: a White House aide had improperly raised funds through a private group while he ran Clinton’s national service corps, Clinton’s first agriculture secretary had accepted improper gifts from companies that his department regulated (including Arkansas-based Tyson Foods), Clinton’s commerce secretary had engaged in improper financial deals, the secretary of Housing and Urban Development had lied to FBI agents during a background check about the size of payments that he had made to a former mistress while he was a Texas mayor, Clinton’s interior secretary had lied to Congress about his role in granting a federal license for a gambling casino, and Clinton’s labor secretary had taken part in an influence-peddling scheme in a former job as a White House aide. None of those investigations produced evidence of illegal activities, although the Housing and Urban Development secretary admitted that he had not been completely truthful about payments to the mistress.

The most troublesome and damaging investigation involved a real estate deal that Clinton and his wife undertook in 1978, while he was attorney general of Arkansas. The investigation became known as “Whitewater,” after the name of the land development company, Whitewater Development Corp., which the Clintons formed with James D. and Susan McDougal of Little Rock. The four had purchased 230 acres of wilderness near the White River and Crooked Creek in Marion County and had lost money when they could not develop and sell the lots. The principal accusation was that the McDougals, and perhaps the Clintons and their real estate project, had benefited from the operations of a Little Rock savings and loan association that James McDougal formed in Little Rock in the 1980s, which eventually went bankrupt. Business deals between the McDougals and a small business lending company in Little Rock run by David Hale, a Little Rock municipal judge, also became a focus of the investigation. The probe was expanded to look into the 1993 suicide of Vincent Foster Jr.—a Little Rock lawyer who became deputy White House counsel—as well as the firing of the White House travel staff and other activities at the White House.

Yielding to Republican criticism, Clinton asked Attorney General Janet Reno in 1994 to appoint an independent counsel on Whitewater. Her appointee, a Republican lawyer named Robert B. Fiske, was later removed by a panel of judges in Washington and replaced with Kenneth W. Starr, who had been solicitor general under President George H. W. Bush.

Starr continued the investigation through the rest of the Clinton presidency. While several Arkansans were indicted in various property dealings in Arkansas, including Governor Jim Guy Tucker, neither the Clintons nor others in his administration were ever implicated in any wrongdoing in the Whitewater-related activities. The investigations concluded that Foster had committed suicide and that the firing of travel staff involved no wrongdoing.

But one part of Starr’s investigation paid off. Agents conducted lengthy inquiries into reports of marital infidelities by Clinton. A former employee of the Arkansas Industrial Development Department, Paula Corbin Jones, filed a lawsuit in 1994 alleging that Clinton had made unwanted sexual advances toward her in a Little Rock hotel room in 1991, and the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that trying the suit would not distract Clinton from his duties as president. In 1998, Linda Tripp, a confidante of Monica Lewinsky, an intern at the White House, gave Starr recordings in which Lewinsky talked about having oral sex with the president. Although the Lewinsky affair was unrelated to any of the Whitewater issues, Starr justified this investigation by saying it was part of a pattern of obstructing justice at the Clinton White House. On September 9, 1998, Starr gave the House of Representatives a lengthy report on Clinton’s indiscretions with Lewinsky, including his efforts to cover them up during testimony before Starr’s grand jury and during a deposition that he gave in the civil case of Paula Jones.

The House Judiciary Committee accused Clinton of “high crimes and misdemeanors,” the grounds for impeaching and removing a president, and brought four articles of impeachment against him. On December 19, voting largely along party lines, the House adopted two of the articles—perjury before the grand jury and obstruction of justice—by votes of 228 to 206 and 221 to 212. Democrats charged that the impeachment proceedings were a Republican vendetta to destroy a popular president. But only the Senate can remove a president, by a two-thirds vote. On February 12, 1999, after hearing lengthy arguments presented by Republican members of the House and by defenders of the president, including a passionate closing argument by former Arkansas senator Dale Bumpers, the Senate defeated the perjury article, forty-five for and fifty-five against, and the obstruction of justice article, fifty to fifty. Starr said he would seek criminal charges against Clinton for the Lewinsky affair after the president left office, but on the day before he left office in January 2001, Clinton issued a statement apologizing for giving erroneous testimony to the grand jury, and Starr closed the investigation. Starr’s independent counsel office did not close until May 2004. Owing to the admission of giving false testimony and proceedings instituted by the Professional Ethics Committee, Clinton surrendered his license to practice law in Arkansas.

Post-presidency

Clinton’s wife decided early in 1999 to run for the U.S. Senate seat in New York being vacated by Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan. She and Clinton bought a house in Chappaqua, New York, to establish residency in New York, and she was elected to the U.S. Senate in November 2000 and again in 2006; she became secretary of state in 2009 and ran for president in 2008 and 2016.

Bill Clinton retired to New York after leaving office on January 20, opened an office in Harlem neighborhood, and began to write his autobiography. The book, My Life, was published in 2004 and became a bestseller. That same year, the University of Arkansas Clinton School of Public Service was established, and Clinton’s presidential library opened in November 2004 on the Little Rock riverfront. He traveled extensively throughout the world, particularly in Africa and Asia, where he instituted efforts to import medicine to combat the AIDS epidemic. In 2005, President George W. Bush appointed Clinton and the elder President Bush to direct humanitarian relief efforts for the victims of a tsunami that killed more than 200,000 people along the coasts of the Indian Ocean on December 26, 2004. Both were also involved in the relief efforts for the victims of Hurricane Katrina in 2005. In 2010, Clinton and George W. Bush created the Clinton Bush Haiti Fund to assist the people of Haiti after an earthquake there in January. In 2013, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama. In 2018, he released his first novel, The President Is Missing, which he co-authored with James Patterson. In 2021, the pair released a follow-up, The President’s Daughter. In 2024, Clinton published another memoir, Citizen: My Life after the White House, and the following year, he and Patterson released another novel, The First Gentleman.

Clinton’s name has been frequently linked with that of Jeffrey Epstein, a financier and sex offender known to have provided prominent men with sexual access to underage girls, especially at Little St. James, his private Caribbean island. Epstein discussed policy with some of Clinton’s presidential staff in the 1990s and attended fundraisers for Clinton. According to flight logs, between 2001 and 2003, Clinton flew multiple times on Epstein’s private plane to various international destinations, but a Clinton spokesman, following Epstein’s arrest in 2019, stated that Clinton had never traveled to any of Epstein’s private residences and had, by that time, not spoken to Epstein in more than a decade. Clinton has not been accused of any wrongdoing in connection to the multiple lawsuits that have spun out of the Epstein case, and his involvement with Epstein was markedly less than that of later president Donald Trump, who regularly attended Epstein-hosted events, and hosted Epstein himself, in the 1990s and early 2000s. Interestingly, Kenneth Starr, the independent counsel who had investigated Clinton’s affair with Monica Lewinsky, served as part of Epstein’s legal defense team following his arrest for sexually abusing thirty-six girls, some as young as fourteen, and helped him in 2008 to secure a lenient plea deal that granted him effective immunity from federal prosecution.

Summary

Clinton was among Arkansas’s most productive governors and brought about extensive reforms in public education. His long tenure ended with an extended period of job creation and moderate economic growth. He was even more ambitious as president but not as successful, partly because he dealt with a largely hostile Congress for the last six years of his presidency. He steered the Democratic Party gently away from its modern liberal tradition that traced back to Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry Truman, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson, but he still succeeded in improving the economic well-being of low-income working families by $20 billion a year, with a combination of health insurance for their children, refundable tax credits for work, and tax credits for college expenses. While economists debated the extent to which his policies were responsible, his presidency marked the longest period of sustained economic growth in the nation’s history and yielded four consecutive years of federal budget surpluses. Clinton was president at the peak of U.S. supremacy in the world, and he personally basked in unprecedented global admiration.

For additional information:

Bennett, David H. Bill Clinton: Building a Bridge to the New Millennium. New York: Routledge, 2014.

Birkett, Chris. Bill Clinton at the Church of Baseball: The Presidency, Civil Religion and the National Pastime in the 1990s. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2023.

Brummett, John. Highwire: From the Backroads to the Beltway: The Education of Bill Clinton. New York: Hyperion, 1994.

Carter, Daryl A. Brother Bill: President Clinton and the Politics of Race and Class. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2016.

———. “President Bill Clinton, African Americans, and the Politics of Race and Class.” PhD diss., University of Memphis, 2011. Online at https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/etd/201/ (accessed July 6, 2023).

Clinton, Bill. Between Hope and History: Meeting America’s Challenges for the 21st Century. New York: Random House, 1996.

———. Citizen: My Life after the White House. New York: Knopf, 2024.

———. My Life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004.

Conanson, Joe. Man of the World: The Further Endeavors of Bill Clinton. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016.

Conason, Joe, and Gene Lyons. The Hunting of the President: The Ten-Year Campaign to Destroy Bill and Hillary Clinton. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000.

Dumas, Ernest C., ed. The Clintons of Arkansas: An Introduction by Those Who Know Them Best. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992.

Fallows, James, et. al. “Bill Clinton and His Consequences.” The Atlantic Monthly 287 (February 2001): 45–69.

Hamilton, Nigel. Bill Clinton, An American Journey. New York: Random House, 2003.

Kalb, Marvin. One Scandalous Story: Clinton, Lewinsky & 13 Days that Tarnished American Journalism. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2001.

Klein, Joe. “Eight Years.” The New Yorker 76 (October 16 and 23, 2000): 188-217.

———. The Natural: The Misunderstood Presidency of Bill Clinton. New York: Doubleday, 2002.

Lamb, Charles M., Joshua Boston, and Jacob R. Neiheisel. “Presidential Rhetoric and Bureaucratic Enforcement: The Clinton Administration and Civil Rights.” Political Science Quarterly 134 (Summer 2019): 277–302.

Levin, Robert E. Bill Clinton, The Inside Story. New York: Shapolsky Publishers, Inc., 1992.

Levy, Peter B. Encyclopedia of the Clinton Presidency. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2002.

Lichtenstein, Nelson, and Judith Stein. A Fabulous Failure: The Clinton Presidency and the Transformation of American Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2023.

Maney, Patrick J. Bill Clinton: New Gilded Age President. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2016.

Maraniss, David. First in His Class: A Biography of Bill Clinton. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995.

Marcus, Alan. “Bill Clinton in Arkansas: Generational Politics, the Technology of Political Communication and the Permanent Campaign.” Historian 72 (June 2010): 354–385.

Mast, Jason L. The Performative Presidency: Crisis and Resurrection during the Clinton Years. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Nelson, Michael. Clinton’s Elections: 1992, 1996, and the Birth of a New Era of Governance. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2020.

Nelson, Michael, Barbara A. Perry, and Russell L. Riley, eds. 42: Inside the Presidency of Bill Clinton. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2016.

Riley, Russell L. Inside the Clinton White House: An Oral History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Root, Paul, ed. To the Grassroots with Bill Clinton. Arkadelphia, AR: The Pete Parks Center for Regional Studies, Ouachita Baptist University, 2002.

Schier, Steven E. The Postmodern Presidency: Bill Clinton’s Legacy in U.S. Politics. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2000.

Sebold, Karen. “How the Social Context of Bill Clinton’s Childhood Shaped His Personality: Using Oral History Interviews of His Childhood Peers and Relatives.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2008. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2485/ (accessed July 6, 2023).

Shields, Todd G., Jeannie M. Whayne, and Donald R. Kelley, eds. The Clinton Riddle: Perspectives on the Forty-second President. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2004.

Siewert, Markus B. “‘It’s Never Easy for the President to Get Exactly What He Wants’: Presidential Activism and Success in the Legislative Arena during the Presidencies of Clinton, Bush, and Obama.” PhD diss., Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universitaet Frankfurt am Main, 2018.

Smith, Stephen A., ed. Preface to the Presidency: Selected Speeches of Bill Clinton, 1974–1992. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1996.

Staley, Carolyn Yeldell. The Boy Next Door: My Sixty-Year Friendship with Bill Clinton. Marion, MI: Parkhurst Brothers Publishers, 2025.

Takiff, Michael. A Complicated Man: The Life of Bill Clinton as Told by Those Who Know Him. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010.

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Daisy Bates with Bill Clinton

Daisy Bates with Bill Clinton  Beef Promotion

Beef Promotion  Clinton and Kelley

Clinton and Kelley  Clinton and Tucker

Clinton and Tucker  Clinton Birthplace

Clinton Birthplace  Clinton Meets Goldwater

Clinton Meets Goldwater  William J. Clinton Presidential Center and Park Dedication

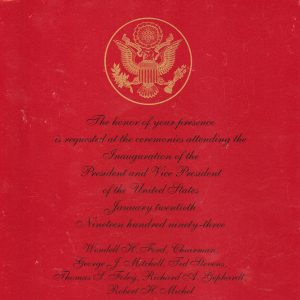

William J. Clinton Presidential Center and Park Dedication  Clinton Presidential Inauguration

Clinton Presidential Inauguration  Clinton Presidential Library and Museum

Clinton Presidential Library and Museum  Clinton Quilt

Clinton Quilt  Bill Clinton with Lions Club

Bill Clinton with Lions Club  Bill Clinton

Bill Clinton  Bill Clinton Signing Act 1092 for Arkansas Children’s Hospital

Bill Clinton Signing Act 1092 for Arkansas Children’s Hospital  My Life by Bill Clinton

My Life by Bill Clinton  Clintons' House

Clintons' House  Bill Clinton Campaign Button

Bill Clinton Campaign Button  Clinton Inauguration Ticket

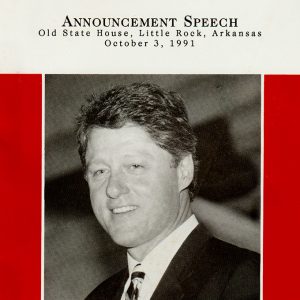

Clinton Inauguration Ticket  Bill Clinton for President Announcement

Bill Clinton for President Announcement  Bill Clinton Presidential Campaign

Bill Clinton Presidential Campaign  Bill Clinton

Bill Clinton  Bill Clinton

Bill Clinton  Hillary and Bill Clinton

Hillary and Bill Clinton  Hillary Rodham Clinton

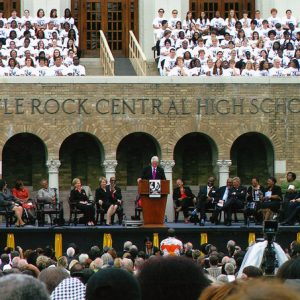

Hillary Rodham Clinton  Desegregation of Central High 50th Anniversary

Desegregation of Central High 50th Anniversary  Five Arkansas Governors

Five Arkansas Governors  Governors' Reunion; 1986

Governors' Reunion; 1986  Bill Clinton at Greers Ferry

Bill Clinton at Greers Ferry  Heifer Project International HQ Dedication

Heifer Project International HQ Dedication  B. B. King and President Clinton

B. B. King and President Clinton  Cone Magie and Bill Clinton

Cone Magie and Bill Clinton  Ozark Frontier Trail Festival

Ozark Frontier Trail Festival

I was born in Fort Smith, Arkansas, in 1957 and resided on a county road north of Van Buren during my youth and early adult life. I worked as a nurse for St. Edward Mercy Medical Center (Mercy Medical Center). I remember the Clinton years well, seeing the state enjoy economic growth for lower- and middle-income families, as well as improved educational standards. We saw better standards for teachers and tax relief for citizens (except for higher taxes for the upper class) while facing opposition from business: trucking, poultry, and wood products. My cousin in Little Rock worked on all Clinton’s races for governor, as well as his first presidential campaign. I first met Bill Clinton at a festival in Fort Smith about a year and a half before he first announced he would run for president. I told everybody–friends, family, coworkers–that he would be president one day soon, meeting a lot of criticism for my comments (I live in a very Republican part of a Republican-leaning state). I have supported him throughout his career, not counting his early run for attorney general of Arkansas. I am extremely proud of his time as governor and later as president of the United States, as well as his humanity efforts with former presidents George Bush and Jimmy Carter. I strongly believe Arkansas and the United States are better for having his leadership during these past forty odd years, and the world as well.

William Jefferson Clinton, in his memoirs, says that he was born William Jefferson Blythe III. Many sources, such as his biography at http://www.whitehouse.gov, agree with that statement. Others say that he was born William Jefferson Blythe IV.

The solution to this puzzle is complicated. The future president’s father and grandfather were both named William Jefferson Blythe. That grandfather was named for an uncle of the same name. Ergo, if one considers only the direct line of fathers and sons, the future president was the third in the line. One could just as easily say that the grandfather’s uncle was the first, the grandfather was the second, making the future president the fourth. In other words, either number is correct.