calsfoundation@cals.org

Education Reform

Education reform, the process of improving public education through changes in public policy, has been slow and often ineffective in Arkansas. All aspects of public education are open to reform, including school finance, teacher quality, curriculum, transportation, and school facilities. Modern education reforms in Arkansas include school choice initiatives, alternative teacher pay, and standards-based accountability and testing.

Arkansas has historically been one of the lowest-performing states academically, and even today, despite major improvements in funding and student achievement during the last decade, Arkansas still ranks below the national average on many objective measures. Arkansas also has one of the most undereducated populations in the nation in terms of the percentage of adults with college degrees and the percentage of high school graduates; Arkansas ranks in the bottom five nationally in both categories. In addition to the low levels of academic achievement, the state’s historically poor education has been due to its reluctance to integrate, its low teacher salaries and per pupil expenditures, its efforts to outlaw the teaching of evolution, and its general lack of legislative support to fund education.

Early Statehood Era, 1836–1880

School reform was not a priority as the state was just beginning to establish a public education system. Governor Archibald Yell (1840–1844) led the early efforts in education reform by advocating a program of state aid for public schools, and Governor Thomas Drew (1844–1849) attempted unsuccessfully to convince the legislature to establish a state college. Public education faced similar difficulties under the next governor, John Roane (1849–1852). Despite the fact that the federal government had set aside land to be sold to raise revenue for new educational institutions, Roane was unsuccessful in persuading the Eighth General Assembly to ensure that localities would dedicate the proceeds of these sales to education. In general, the antebellum era in Arkansas was marked by repeated governmental budgetary shortfalls, and supporting public education at any level was not a high priority for the state. Although the pre–Civil War Arkansas state constitution had a general clause about supporting public education, it was not until after the war that the constitution required a system of free schools in the state.

The Gilded Age through the Progressive Era, 1880–1921

In 1885, Governor Simon Hughes (1885–1889) instituted the first round of special education reform in Arkansas by establishing the Deaf Mute Institute (now the Arkansas School for the Deaf) and the Institute for the Blind (now the Arkansas School for the Blind) at state expense. Hughes and other governors during the late nineteenth century continued to struggle to bring the state into financial solvency, and most education reforms lacked financial support.

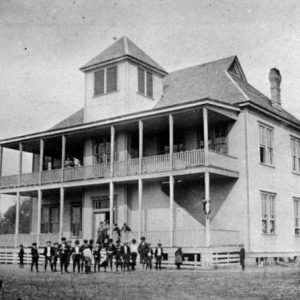

During the governorship of Xenaphon Pindall (1907–1909), the first major reform to professionalize teaching occurred with the founding of the Arkansas State Normal School (ASNS) in Conway. This institution for teacher training became the Arkansas State Teachers College (ASTC) in 1925 and ultimately the University of Central Arkansas (UCA).

One influential education reform governor was George Donaghey (1909–1913). Donaghey invited the Southern Education Board, an organization dedicated to reforming public education in the region, into Arkansas. During Donaghey’s tenure, secondary and higher education made important steps forward, as four agricultural high schools were established that later became Arkansas Tech University (ATU), Southern Arkansas University (SAU), the University of Arkansas at Monticello (UAM), and Arkansas State University (ASU). Donaghey’s governorship also saw a state law that made consolidation of rural schools less complicated.

The early twentieth century is often referred to as the progressive era of education reform, and in Arkansas, former professor Charles Brough was a supporter of progressive education as governor from 1917 to 1921. Brough was one of the first governors to get the General Assembly to pass a law that would allow for property taxes, or millage, to be used for the funding of state educational institutions. Brough also established a compulsory attendance law, an illiteracy commission, and support both for vocational education and special education.

The Early Twentieth-Century Era, 1921–1953

Thomas McRae (1921–1925) was another influential education reform governor in Arkansas history. The post–World War I climate in Arkansas was turbulent, and the state was in financial distress. During this time, the average school year was only 131 days, with twenty-five percent of students in school less than 100 days. Rural areas lacked high schools, and over 100,000 Arkansas adults were illiterate. During McRae’s first term, the General Assembly adjusted the state property tax in order to supply a stable revenue source for the support of educational institutions, including the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County). However, it was difficult for McRae to pass other tax measures for the support of education.

At this time, the state government was only supplying $2.60 of the average local per student expenditure per year, which was a mere $23.63 as compared to approximately $60 in Oklahoma and Missouri. Nonetheless, the General Assembly would not support an income tax to finance education. The legislature did, however, pass a tobacco tax, which helped enrich the education fund. By the time he left office, McRae had doubled the state’s per pupil contribution. Between the governorships of McRae and Harvey Parnell, the only major reform was that the public voted in 1926 to allow local districts to raise their property tax from twelve to eighteen mills.

Governor Parnell (1928–1933) finally got an income tax through the General Assembly in 1929 as a way to support public education. Shifting a portion of the tax burden from rural Arkansans whose wealth lay in property assets to urban dwellers dramatically improved the amount of revenue available for education. An advocate of consolidation as a way to help rural education, Parnell worked with interest groups and legislators to close hundreds of one-room school houses across the state. His reforms led to widespread school bus use, a twenty-percent increase in high school enrollment, and a lengthening of the school year. Parnell also supported teacher training through the establishment of Henderson State Teachers College (now Henderson State University) in Arkadelphia (Clark County) in 1929.

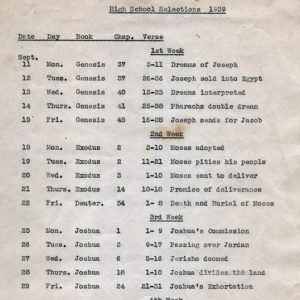

Curriculum reform also occurred during this time. In addition to a 1930 state law that required public school teachers in Arkansas to read Bible verses, Arkansas was one of only four states to pass a law prohibiting the teaching of evolution. Additionally, the Arkansas Education Association (AEA), the state’s most prominent educator advocacy group, became very active during this time as a reform organization. Two aspects of the AEA’s agenda were for the state to focus revenue on primary education rather than higher education and to use urban wealth to fund rural schools. In addition, the State Teachers Association of Arkansas, the state’s African-American educator organization, attempted to improve the quality of education for black students during the 1920s. The association tried to address the inequities resulting from the local autonomy in spending state education money. For example, in Chicot County during the 1929–30 school year, the per-pupil expenditure was only $6.36 for black students, compared to $54.11 for white students.

The reforms of this era did little to persuade Governor Junius Futrell (1933–1937) that education should be a state priority. Futrell did not believe that the state should fund education beyond the eighth grade. Moreover, he wanted the federal government to bear the costs of education, and only when the federal government threatened to withdraw support did Futrell assent to the legislature’s two percent retail sales tax to support public education.

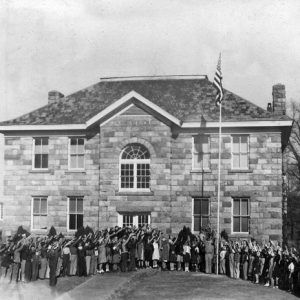

Although the federal government did not support Futrell’s education policy, it did contribute considerable resources through New Deal programs of the 1930s for the construction of school facilities. These building programs, along with the reforms of consolidation and statewide district reorganization during the 1940s, contributed further to the desertion of many one-room schoolhouses across the state.

The Desegregation Era, 1954–1971

The tenure of Orval Faubus (1955–1967) was an eventful period of education reform for Arkansas, as the state became a central figure in the anti-integration movement of the 1950s and 1960s. In the landmark desegregation case of 1954, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation of public schools was unconstitutional. White supremacy groups in Arkansas did not accept the Brown ruling and attempted to delay integration as long as possible through intimidation and boycotts. The first battle over integration occurred in Hoxie (Lawrence County). Ultimately, the school board at Hoxie ended up suing the segregationists for their efforts at obstruction, and through federal judicial intervention, integration in Arkansas took a slow step forward.

The segregationists were not defeated, however. With Governor Faubus as their political ally, segregationists next tried to delay the integration of Central High School in Little Rock (Pulaski County). On the grounds that he was preserving order, Faubus called in the National Guard to prevent black students from entering Central High on September 4, 1957. In the end, the federal courts ordered Faubus to allow the integration to take place, and President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent federal troops to ensure that black students could attend school safely.

Although teacher salaries grew by 125 percent between 1954 and 1966, Faubus’s failure to support the school board in Hoxie and his response at Central High did little to promote support for integration or to improve the image of the state’s public education system.

The Modern Era, 1971 to the Present

Education reform progressed after Faubus left office. In cooperation with the legislature, Governor Dale Bumpers (1971–1975) passed multiple reforms. Some of the more prominent legislation during Bumpers’s tenure consisted of state-funded kindergarten, free high school textbooks, and special education funding reform. During the administration of David Pryor (1975–1979), the AEA was prominent in opposing tax reform that would shift the responsibility for funding education to the localities. In 1977, the General Assembly did, however, pass legislation to establish the minimum foundation funding level for state aid to public schools.

Governors Bill Clinton (1979–1981, 1983–1992) and Mike Huckabee (1996–2007) were perhaps the most education reform–oriented governors in the history of the state. The major contribution of Governor Frank White (1981–1983) to education was his support of a bill that put creationism on par with evolution; in doing so, White contributed to the negative reputation of Arkansas education.

In his first term, Clinton stated that education was his top legislative priority, and his agenda promoted new teacher competency examinations, standardized student achievement testing, widespread consolidation, and a “fair dismissal” law to protect teacher tenure. Clinton was unsuccessful, however, in getting legislative support to raise taxes to support these reforms.

In 1983, the state Supreme Court ruled in Dupree v. Alma School District that the state’s funding formula was unconstitutional. This ruling and the federal A Nation at Risk report gave momentum to Clinton’s education agenda during his second term. The Education Standards Committee, which was headed by state first lady Hillary Rodham Clinton, concentrated on bringing higher teacher quality, a more rigorous curriculum, a longer school year, and smaller class sizes to the state. Governor Clinton connected school consolidation to these new standards, and this time, he was able to raise the state sales tax by one percent to fund his reforms. The AEA stridently opposed his teacher testing initiative but ultimately benefited during this period by gaining large increases to teacher salaries.

In 2001, education reform during Governor Huckabee’s administration was also affected by a school funding lawsuit, Lake View v. Huckabee, and a federal education reform initiative, the No Child Left Behind Act. In Lake View, the court again found the state’s funding system unconstitutional. As a result, the legislature enacted comprehensive legislation to modify the funding formula, increase teacher pay, improve facilities, and impose an extensive standardized testing program. The reforms enacted during Huckabee’s administration significantly improved the condition of public education in the state and the reputation of the education system.

The focus of state policymakers on reforming public education continued under the administration of Governor Mike Beebe (2007–2015). For example, during the Eighty-sixth General Assembly, the state approved the largest single capital expenditure for education in Arkansas history by committing $456 million to improve school facilities.

Though much progress has been made in Arkansas to improve public education in recent years, education reform in Arkansas has historically been a slow and contentious process. All three branches of government have been involved in changing education policy, but the state’s governors have perhaps been most instrumental, for better or worse, in these reforms.

For additional information:

Clement, R. Davis, II. “Education Reform as Moral Disengagement: The Racist Subtext of the State Takeover of the Little Rock School District.” PhD diss., College of William and Mary, 2018.

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard B. Gatewood, and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Johnson, Ben F. “‘All Thoughtful Citizens’: The Arkansas School Reform Movement, 1921–1930.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 46 (Summer 1987): 105–132.

Klotz, Daniel. “State Power and School Reform in Faulkner County, 1873–1931.” MA thesis, University of Central Arkansas, 2016.

Ledbetter, Calvin R., Jr. “The Fight for School Consolidation in Arkansas, 1946–1948.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 65 (Spring 2006): 45–57.

Leveritt, Mara, and Judith M. Gallman. “Grading the Gov.” Arkansas Times, November 1990, pp. 34–43.

McAndrews, Lawrence J. The Era of Education: The Presidents and the Schools, 1965–2001. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2006.

Rutherford, Blake S. “Progress to Privatization: The Curious Case of Education Reform in Arkansas, 1983–2024.” In Post-Truth’s Assault on America’s Schools and Colleges, edited by Joseph L. DeVitis. Leeds, UK: Emerald Insight, 2026.

Tyack, D., Thomas James, and Aaron Benavot. Law and the Shaping of Public Education, 1785–1954. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987.

Marc J. Holley

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.