calsfoundation@cals.org

Timber Industry

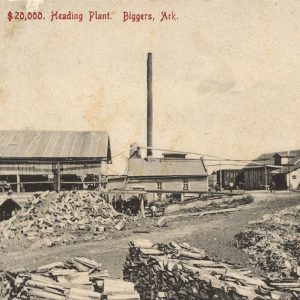

The timber industry in Arkansas developed in all directions after the Civil War. The abundant forests of the state made it possible over the years to produce lumber, kraft paper, fine paper, newsprint, chemicals, charcoal, and many other products. The industry’s development depended first upon the availability of abundant forests. From Little Rock (Pulaski County) in central Arkansas to the north, west, and south are forests and marketable timber. To the east is the Delta, where hardwood grows in the swamps and river bottoms. The Ozark Mountains in the north are home to a mix of slower-growing pine and hardwood. The Ouachita Mountains to the west abound in pine on the slopes and hardwood in the valleys. The rolling hills to the south contain more pine—generally yellow pine. The pine grows more quickly in the sandy soils and warm climate of south Arkansas than in the Ouachitas or the Ozarks. Hardwood grows in the swampy river bottoms.

From the earliest European exploration by Hernando de Soto in the 1500s through the Civil War in the 1860s, these forests were obstacles to travel and settlement. To a handful of hardy pioneers who cleared homesteads, the trees were best cleared for farming.

After the Civil War, the development of powered machinery allowed individuals to set up small sawmills. But these served only the local communities. The means to get lumber to larger, growing markets in the Northeast and the Midwest did not exist until railroad builders saw opportunity and began to extend their lines into Arkansas and Texas. Samuel Fordyce, a Civil War veteran from the Union side who spent time after the war recuperating in Hot Springs (Garland County), built the Cotton Belt railroad from St. Louis, Missouri, to Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), Camden (Ouachita County), and on to Texas.

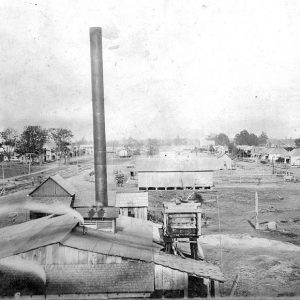

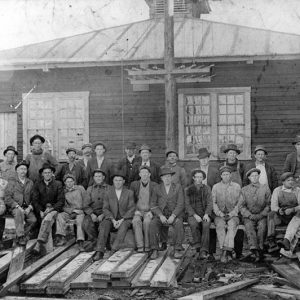

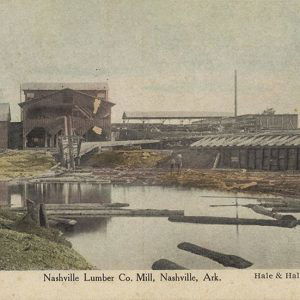

Once the mainline was in place, Northern lumber entrepreneurs from Illinois and Iowa—including Moses Franklin Rittenhouse, John William Embree, Frederick E. Weyerhaeuser, Dr. John Wenzel Watzek, Charles Warner Gates, and Edward Savage Crossett—began to acquire timberlands, especially in south Arkansas. Watzek, Gates, and Crossett founded the Fordyce Lumber Company at Fordyce (Dallas County) in 1892 and the Crossett Lumber Company at Crossett (Ashley County) in 1899; Rittenhouse and Embree established the Arkansas Lumber Company at Warren (Bradley County) in 1901; Weyerhaeuser founded the Southern Lumber Company in Warren in 1902. These and other entrepreneurs hired men, created feeder lines into the forests, built large sawmills, and began to harvest the virgin pine. Over time, additional power equipment—such as tree cutters, road building machinery, haulers, and material management tools—supported larger operations.

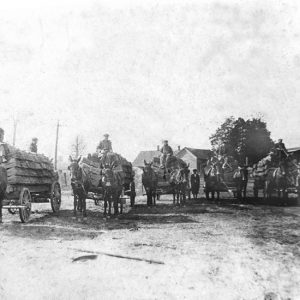

The relationship between railroads and the timber industry was mutually beneficial. The railroads needed cross ties and products to carry to market; the timber industry needed transportation and the mechanical skills supplied by railroad men. As the timber industry mechanized, men with metal-working skills in the railroad repair shops in Pine Bluff and Camden found jobs in the large lumber mills.

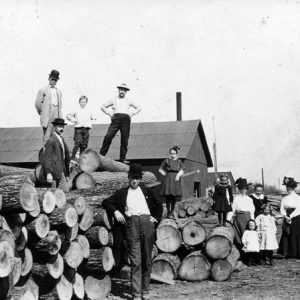

Between 1880 and 1920, community development enjoyed a similar beneficial relationship with the timber industry. Camden and Pine Bluff both predated the railroads and the timber industry. Camden, on the Ouachita River, had a cloth-manufacturing industry before and during the Civil War. Pine Bluff, on the Arkansas River, had long served Delta cotton growers. Fordyce and Warren owed their existence to the local farm economy and the development of railroads. Crossett developed out of virgin pine forest, first as a sawmill camp, then as a company town to house workers and their families.

When the timber industry arrived in a town, many new services and institutions—schools, churches, stores, police and fire departments, hospitals, newspapers, and utilities—were needed to support the growing numbers of employees and their families. Generally, when families arrived, entrepreneurs followed to create the support functions essential to a modern city.

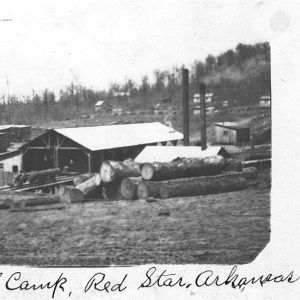

The prosperity had drawbacks. Timber-cutting operations, even large ones, practiced a technique known as “cut out and get out” until the 1920s and later. With this method, a company would enter an area, buy one or more parcels of virgin timber, build a sawmill and production facilities, cut all the marketable trees out of each parcel, mill it and ship it, and move on to another parcel. The chief difference between a large operation and a small one was that the smaller operation bought smaller areas of land and produced less lumber, using a more modest production plant. The larger operations bought much greater areas of land, built large sawmill plants, and left them in place as they shipped raw logs over rail lines that they built to them. The distinguishing characteristics of the “cut out and get out” method were large areas of denuded land and periodic relocation of the production facilities. For towns whose livelihood relied on the timber industry, relocation of production meant the town’s decline and possible death.

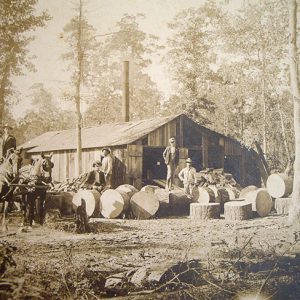

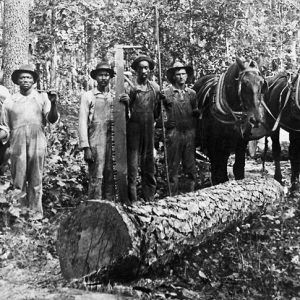

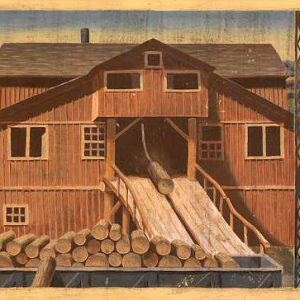

In 1900, timber processing was fairly straightforward. Contractors, or company employees, extended the company logging railroad into the woods as needed, selected a tree, trimmed its branches, cut it down, rough-sawed it into manageable log sections, and skidded it out of the woods to the rail head using mule teams. They would then load the logs onto the company logging railroad cars. Once logs made it to the sawmill, they were sorted by size, cut into boards, planed, dried, and seasoned before being shipped to the lumber markets by rail.

By the mid-1920s, owners of huge timber acreages in south Arkansas, such as the Crossett-Watzek-Gates group and International Paper, began to notice a new phenomenon. Timberlands cleared at the turn of the century had new, usable forests. The forest was growing back, and it was growing quickly compared with northern forests, where regrowth could take fifty years or more. But a small group of professional foresters had been studying the problem for more than a decade.

U.S. pioneers in scientific forest management had established the first college-level forestry schools in the 1890s and 1900s. Gifford Pinchot, a Yale University graduate, trained in forestry at the French Forest School in Nancy, France. On his return to the United States, Pinchot began experimenting with continuous forest regrowth at the Biltmore Estate in Ashville, North Carolina, in 1892. He then further refined this process, known as sustained yield forestry. In 1898, Cornell University offered a degree program in scientific forestry, and Pinchot was instrumental in launching a master’s degree program in practical forestry at the Yale University School of Forestry in 1900. Professionals from those programs began to view pine forests as a crop and to communicate their message to forest owners all over the South.

In 1926, Edgar Woodward “Cap” Gates, hands-on manager of the Crossett Lumber Company since its 1899 founding, contacted Professor H. H. Chapman of the Yale forestry school for advice about sustained yield. Chapman, who had conducted camps in Urania, Louisiana, for several years for Yale forestry students, advised Gates to hire a professional forester. Gates hired W. K. Williams and began a tradition of professional forest management at Crossett. Arkansas visionaries such as L. K. Pomeroy, E. P. Connor, A. E. “Wack” Wackerman, and R. R. Reynolds joined national forestry figures to spread the message of sustainability across the country. The management techniques used in Arkansas are still being applied to U.S. forests.

Technical specialists and owners of the Arkansas timberlands grappled with the problems of reducing waste, using smaller trees, and producing more diversified products. A long string of useful developments occurred between 1926 and 1980 to accomplish these objectives. Collectively these improvements are known as process orientation because they incorporated technology-based processes to add value to basic forest products. In 1928, International Paper opened a kraft paper mill in Camden. Kraft paper is used to make cardboard boxes and heavy-duty wrapping paper. By 1968, the Camden mill employed 2,100 and turned out more than 500 tons of paper a day. Crossett opened a chemical company to produce turpentine, acetic acid, wood alcohol, and other commercially useful chemicals from wood waste. By 1960, Crossett had opened a kraft paper mill, a food board plant that made milk cartons and frozen-food packaging material, and a flake board plant that made sheets of boards used much like plywood. In 1963, Crossett Lumber Company’s successor, Georgia-Pacific, opened a first-of-its-kind pine plywood plant in Fordyce. International Paper opened another kraft mill in Pine Bluff.

Process orientation meant more stable business conditions and steady employment. Throughout the twentieth century, other companies, large and small, were active across the state. Dierks Forests, Inc. purchased by Weyerhaeuser in 1969, had large lumber operations in Mountain Pine (Garland County) and other communities in the Ouachitas. Potlatch had a large lumber operation in Warren and kraft mills in Pine Bluff and McGehee (Desha County). Anthony Timberlands had a large lumber and forest products operation in Bearden (Ouachita County), and Green Bay Packaging had a kraft mill and lumber operations around Morrilton (Conway County). International Paper had lumber operations in Malvern (Hot Spring County), Leola (Grant County), and many other small towns.

In 1998, one-sixth of all manufacturing jobs in Arkansas—43,000—were in forest product harvesting and manufacturing. There were 2,500 companies in the forest product business, and they supported $1.2 billion in payroll, the largest of any manufacturing sector. Of two and a half million acres of forestland, private landowners owned fifty-eight percent, timber manufacturing firms owned twenty-five percent, and the public owned seventeen percent, largely as national forest. Since World War II, Arkansas’s forests have been sustained.

The success of the timber industry in Arkansas has been accompanied by controversy on several fronts. Process orientation led to significant unionization of the paper mills and other processing facilities. There were notable labor strikes in Crossett in 1940 and 1985. Sustainable forest management practices, such as clear-cutting and the replacement of native timber stands with more marketable pine plantings, have drawn criticism from environmentalists and outdoorsmen alike. Paper and chemical operations have drawn the attention of the environmental agencies of the federal government. National Forest management practices have been questioned. And, finally, forest product market conditions have led to periods of economic distress for companies and communities in Arkansas.

Beginning in 2008, the wood products industry suffered due to the downturn in the American economy. Demand for lumber in the housing industry declined as fewer houses were being built. In September 2011, for example, the Georgia-Pacific Company announced the indefinite suspension of production and the layoff of about 700 workers in its Crossett plants. The layoff of thirty-six employees of the Arkansas Forestry Commission in late 2011 added to the image of a depressed industry.

The recovery of the housing market has, in time, improved the outlook of the wood products industry. It is uncertain whether that industry will return to its former prominent position as a producer of housing materials, shift to other ways of marketing the natural timber resources, or assume a smaller role in the state economy. The impact on the people and communities that rely on the industry also remains uncertain.

For additional information:

Arnold, Margaret. “Clear-Cutting in Arkansas: How Much Is Enough?” Arkansas Times, September 1979, pp. 34–42.

Balogh, George W. Entrepreneurs in the Lumber Industry: Arkansas, 1881 –1963. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1995.

Barrett, John W., ed. Regional Silviculture of the United States. New York: The Ronald Press, 1980.

Bragg, Don. “Cypress Lumbering in Antebellum Arkansas.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 42 (December 2011): 185–196.

Buckner, John W. Wilderness Lady. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1979.

Clark, Thomas D. The Greening of the South: The Recovery of Land and Forest. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1984.

Cottingham, Jan. “Arkansas Timber Industry Reborn.” Arkansas Business, November 26–December 2, 2018, pp. 1, 16–17.

Cox, Thomas R., Robert S. Maxwell, Phillip Drennon Thomas, and Joseph J. Malone. This Well-Wooded Land: Americans and their Forests from Colonial Times to the Present. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1985.

Darling, O. H. “Doogie,” and Don C. Bragg. “The Early Mills, Railroads, and Logging Camps of the Crossett Lumber Company.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 67 (Summer 2008): 107–140.

Forrester, Jami Marie. “From Swamp Forest to Cotton: Three States Lumber Company and the Development of Burdette, Arkansas in the Early Twentieth Century.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2011.

Martin, Richard. “The Last Stand.” Arkansas Times, August 19, 1993, pp. 14–15.

Minchin, Timothy J. “Torn Apart: Permanent Replacements and the Crossett Strike of 1985.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 59 (2000): 31–58.

Smith, Kenneth L. Sawmill: The Story of Cutting the Last Great Virgin Forest East of the Rockies. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1986.

George W. Balogh

Conway, Arkansas

Mary M. Swanson: Joseph Joshua Brown is my second-great-uncle. His father was Isaac Brown, born in Utica, New York, in 1803, and moved to Maryland at the age of nineteen. He married Annie Wesley in 1825 in Baltimore, with all of his children being born in Maryland. Isaac was a sawyer in Maryland and had quite a few patents for improvements to sawmills. (I have the original model of one that has an engraved plate that says “I. Brown, 1863.” This is how I began my search for him!) His sons followed in his footsteps and became sawyers.

According to Joseph’s obituary and the “Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Pulaski, Jefferson, Lonoke, Faulkner, Grant, Saline, Perry, Garland and Hot Spring Counties, Arkansas, Comprising A Condensed History of the State Biographies of Distinguished Citizens[Etc.]” Author: Goodspeed, firm, publishers, Chicago. (1886-1891. Goodspeed publishing Company):

In 1862, Joseph enlisted in Woodruff Battery and fought throughout the Civil War for the Confederacy until surrendering in Little Rock in 1865. At this time, Joseph married Margaret E. Dickson in August of 1865 and he and his brother opened the first circular sawmill in Little Rock, continuing in that trade until 1875, when he came to Gifford, Hot Springs, Arkansas, and established a large lumber manufacturing business. At the time of the above-cited publication, he employed twenty-five hands and turned out 25,000 or 30,000 feet of lumber daily. In addition to his mill he owned about 15,000 acres of timber land.

In 1899, Joseph moved his family to Los Angeles, California, and became the founder of the Los Angeles Paper Manufacturing Company. He was still the active president at the time of his death at the age of 90 (Feb 1928), which was a result of being hit by an automobile in LA.

Joseph was also a member of the Masonic Order.

One of my ancestors, Joseph Brown (who also served in the Civil War), built the first circular saw in Little Rock, Arkansas, for milling the lumber.