calsfoundation@cals.org

My Life

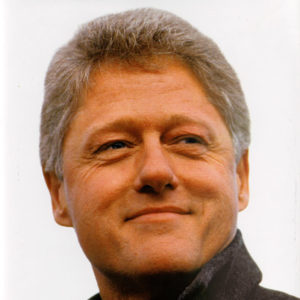

My Life is the autobiography of William Jefferson Clinton, a former governor of Arkansas and the forty-second president of the United States, and was written during the three years after he left the office of president in 2001. The 957-page book, published in hardcover in 2004 by Alfred A. Knopf of New York, was the most thorough memoir of a presidency ever published and the most financially successful. Knopf ordered a first printing of one and a half million copies, but two million orders were received before its release; the company ordered a second printing of 1,075,000. On the day of its release, booksellers sold more than 400,000 copies.

Clinton had received a ten-million-dollar advance to write the book, which lifted him out of debt and made his family wealthy. Clinton and his wife had accumulated nearly twelve million dollars in legal bills defending themselves in numerous investigations during Clinton’s presidency, and the bills were finally paid one year after the publication of My Life. My Life was published a year after Hillary Clinton’s Living History, which stimulated interest in her husband’s forthcoming memoir and contributed to their financial solvency.

Bill Clinton moved to Chappaqua, New York, after he left office because his wife, the former first lady, had been elected U.S. senator from New York in the 2000 election. In a remodeled barn behind the house, Clinton assembled memorabilia from his life and wrote the book. The handwritten narrative filled more than twenty thick notebooks. In an interview on a CBS television show before the book’s release, Clinton said, “When I was a young man, getting out of law school, I said one of the goals I had in life was to write a great book. I have no earthly idea if it’s a great book. But it’s a pretty good story.”

Critics tended to agree that it was not a great book but rather an extraordinary one for the magnitude of the recollection and detail and for the fact that it was done without the help of a professional writer. Still, some critics said the book was self-serving because it glossed over the events that led to so many investigations and that it was made needlessly long by the detailed recapitulation of events that were widely reported at the time. Although rich with anecdotes about Clinton’s upbringing, political campaigns, and the workings of the White House, it made no fresh revelations about the preponderant events of Clinton’s life. When the book was published, the sex scandal that led to Clinton’s impeachment in 1999 was fresh in the public’s mind, and there was anticipation that the former president would illuminate those events. He wrote little of the real and alleged escapades but much about the pain they caused him and his family, recalling that he slept on sofas at the White House for two months after revealing to his wife and daughter that he had lied about his relationship with White House intern Monica Lewinsky.

Most poignant are the recollections of growing up in Hope (Hempstead County) and Hot Springs (Garland County) in the discordant or dysfunctional households of his maternal grandparents and of his mother and violent stepfather. In later chapters, he would blame the indiscretions of his presidency on the unconquered demons of his youth.

Accounts of the last quarter-century of his political career, from the first political races in Arkansas in the 1970s through the eight years in the White House, were a massive compendium of people, places, stories, and speeches that some critics found tiresomely detailed. The index ran thirty pages.

The final two-thirds of the book comprise an almost day-to-day chronology of the two campaigns for the presidency and the affairs of governing for eight years. It provides a glimpse of presidential decision-making and the workings of the White House unmatched in political literature. It recounts in detail the internal debate in 1992–93 on whether to stimulate the economy with public investments and a tax cut or to attack the nation’s budget deficit with spending reductions and a tax increase, as well as the bitter argument in 1994 on whether to appoint a special counsel to investigate the Clintons’ 1978 investment in a real-estate development in Marion County, Arkansas, called Whitewater. His communications director, George Stephanopoulos, persuaded the president to have his attorney general appoint an independent counsel, which Clinton would describe as the worst decision of his presidency. It resulted in his eventual impeachment, though on charges arising from his dalliance with a female intern.

Private anecdotes often humanized historic events of his presidency. Preparing for the historic signing of a peace agreement between Israel and the Palestine National Authority at the White House on September 13, 1993, Clinton exercised diplomacy to arrange a public handshake between Yitzhak Rabin, prime minister of Israel, and Yasser Arafat, president of the Palestinian National Authority, which would be seen around the world; he then rehearsed elaborately with an aide on how to use body language to prevent Arafat from kissing him and then trying to kiss Rabin.

As a literary and historical document, My Life exceeded every presidential memoir but one, President Ulysses S. Grant’s monumental Personal Memoirs. However, Grant’s memoirs were almost completely a recapitulation of his commands in the Mexican War and the Civil War rather than of his presidency.

For additional information:

Clinton, Bill. My Life. New York: Knopf, 2004.

Hertzberg, Hendrik. “The Politician.” The New Yorker. August 2, 2004, p. 79–83.

McMurtry, Larry. “His True Love Is Politics.” The New York Times. July 4, 2004, pp. 1, 8–9.

Simpson, David. “The Kid Who Talked Too Much and Became President.” London Review of Books. September 23, 2004, available online at http//www.lrb.co.uk/v26/n18/simp01_.html.

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

My Life by Bill Clinton

My Life by Bill Clinton

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.