calsfoundation@cals.org

Mount Holly Cemetery

Located in Little Rock (Pulaski County), Mount Holly Cemetery is often called the Westminster Abbey of Arkansas, a name that seems justified by the great number of individuals of significance in the fields of art, literature, religion, and politics who are buried there. Eleven Arkansas governors are interred therein, as well as thirteen Arkansas Supreme Court justices, four United States senators, four Confederate generals, and twenty-one Little Rock mayors.

Mount Holly Cemetery dates from February 23, 1843, when ground was deeded by two leading citizens, Chester Ashley and Roswell Beebe, to the city of Little Rock. The cemetery is located on a four-square-block site between 11th and 13th streets and from Broadway to Gaines Street. Before the establishment of Mount Holly, burials were made in private family cemeteries and a public burial ground on what would first become the Peabody School site and later the location of the present-day Federal Building at Capitol Avenue and Gaines Street. A number of grave markers with dates predating the formation of Mount Holly represent reinterments from the Capitol Avenue site.

Feeling the town fathers were not giving the cemetery the attention it deserved, a group of Little Rock businessmen formed a cemetery commission on March 20, 1877. Charter members of the commission were J. H. Haney, Fay Hempstead, James Austin Henry, Philo O. Hooper, and Frederick Kramer. This form of cemetery administration continued for almost forty years, until a contingent of the town’s women became critical of the cemetery’s unkempt appearance and took over the reins from the men. Following adoption of City Ordinance No. 2199 in June 1915, the ladies’ Mount Holly Cemetery Association was incorporated on July 20, 1915; it continues in that role.

A national study made in 1940 indicated that Arkansas had fewer foreign-born residents than any other state in the union. This demographic statistic is borne out by the cemetery’s burial index, which indicates that most of the early deceased were native-born. On March 7, 1843, a city ordinance designated a portion of the cemetery for Catholic burials, but with the formal opening of Little Rock’s Calvary Cemetery on Asher Avenue in 1872, most Catholic burials were thereafter made there. Between 1860 and 1862, early members of Little Rock’s Jewish community made use of twelve lots purchased exclusively for their use. Many of these remains were removed to Oakland Cemetery (on Little Rock’s east side) between 1913 and 1916, when its Jewish section became available. Section 9 of a March 7, 1843, city ordinance called for a portion of Lot No. 210 at Mount Holly to be set aside for the interment of African Americans, described in the ordinance as “deceased persons of color.”

A representative few of the many noteworthy citizens buried at Mount Holly are: Elias N. Conway, territorial auditor and governor of Arkansas; John H. Crease, a founder of Little Rock’s Christ Episcopal Church; Matthew Cunningham, first mayor of Little Rock (1832), his wife, Eliza Bertrand Cunningham, the first white female resident of Little Rock, and their son, Chester, the first white child born in Little Rock; Cherokee chief John Ross’s wife, Elizabeth Ross (known as Quatie), who died on a steamship en route to Indian Territory on the Trail of Tears in 1839; Sanford Faulkner, who popularized the Arkansas Traveler in song and legend; Isaac Folsom, for whom Folsom Clinic (at the University of Arkansas Medical Center) is named; John Gould Fletcher, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1939, and his wife, the writer Charlie May Simon, known nationally for her children’s works; Augustus Hill Garland, U.S. senator and attorney general of the United States; Herndon Haralson, spoken of as a friend of Sam Houston; John Netherland Heiskell, editor of the Arkansas Gazette from 1902 to 1972; George Izard, a major general in the War of 1812 and Arkansas territorial governor; George R. Mann, an architect of the present State Capitol building; Naorooz Rustam, a Zoroastrian, born in Persia; Ambrose H. Sevier, minister to Mexico; Cephas Washburn, a Presbyterian missionary to the Indians, who preached the first Little Rock sermon in 1820; his son, artist Edward Payson Washburne (who used an alternate spelling of the family surname), best known for his oil painting, the Arkansas Traveler; John Wassell, finishing contractor for the Old State House and mayor of Little Rock by military appointment in 1868; Isaac Watkins, in whose home the first local Baptist church was organized in 1824; Dr. Thomas Welch, founder of the first Presbyterian church in Arkansas; Edward M. Weigel, who discovered bauxite in Arkansas in 1887; William E. Woodruff, founder of the Arkansas Gazette in 1819; W. B. Worthen, early banker and founder of Worthen Bank in 1877; and Weldon E. Wright, who financed the Brooks-Baxter War, a local post-Civil War political disturbance.

Confederate generals resting at Mount Holly include Thomas J. Churchill (who also served as governor), James Fleming Fagan, Allison Nelson, and John Edward Murray, who was killed at the Battle of Atlanta the day his nomination was confirmed.

Of the eight founders of the Medical Department of Arkansas Industrial University (now the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences) in 1879, six are buried at Mount Holly, including Augustus L. Breysacher, the attending physician at the birth of General Douglas MacArthur at the officers’ quarters in Little Rock’s City Park (later renamed MacArthur Park).

As befits its City of Roses location, the cemetery’s many varieties of old roses, mature trees, handcrafted signs that identify its narrow lanes, and styles of its structures give Mount Holly a look of understated Victorian elegance. Its Victorian ambience is further reflected in its grave markers, which exhibit interesting iconographic motifs and epitaphic material and include a number of white bronze markers (manufactured only between 1875 and 1915). Several grave markers are the work of mainstream American stone carvers, and the marker for Albert Pike’s family (which Pike designed) is the work of Robert Eberhard Launitz, said to be the father of monumental art in America. Mount Holly’s collection of cemetery furniture includes a number of very old cast iron pieces, and ornate iron fencing encloses several older lots. A handsome cast iron fountain, a nineteenth-century product of the famous J. L. Mott Company of Bronx, New York, has been at the cemetery since 2002. With cremation’s growing popularity, both locally and nationally, a columbarium was completed in 2003 to the west of the handsomely landscaped fountain.

The burial plots of Elbert H. English, Fay Hempstead (a poet laureate of Freemasonry), and Samuel Calhoun Roane (organizer of the first Masonic lodge in Arkansas Territory in 1819 and designer of the seal of Arkansas Territory) draw attention to the Masonic order. Though Albert Pike, prominent in international Masonic circles, is buried in Washington DC, family members are buried at Mount Holly. Indicative of their standing, ten persons buried at Mount Holly have counties named for them: Ashley, Conway, Faulkner, Fulton, Garland, Izard, Johnson, Newton, Sevier, and Woodruff.

In 1884, 640 Confederate soldiers buried in Mount Holly (troops belonging to commands from Missouri, Arkansas, Texas, and Louisiana) were removed to Oakland Cemetery, with a monument erected there in their honor by trustees of the Mount Holly Cemetery Commission. Structures within the cemetery offer a wide range of architectural styles and include private mausoleums, a community mausoleum, a sexton’s cottage, a picturesque Carpenter Gothic bell house, and a receiving house dating back to 1897, which was restored in 1996. The community mausoleum, designed by Charles L. Thompson, a noted Little Rock architect, is reminiscent of the style of John Russell Pope, architect of the National Archives in Washington, and typical of the period from 1915 to 1925.

Mount Holly was one of the earliest cemeteries to be placed on the National Register of Historic Places (March 5, 1970), and in 1993, its sesquicentennial anniversary was highlighted by the publication of Jubilee, an illustrated cemetery history, and a burial index with every name listed.

On the morning of April 20, 2016, the cemetery’s sexton discovered that the cemetery had been vandalized, including damage to nearly a dozen monuments and the cemetery’s flags. The damage totaled more than $290,000.

For additional information:

Crawford, Sybil F. Jubilee: The First 150 Years of Mount Holly Cemetery, Little Rock, Arkansas. Little Rock: August House, 1993.

Crawford, Sybil F., and Mary F. Worthen. Mount Holly Cemetery, Little Rock, Arkansas, Burial Index, 1843–1993. Little Rock: August House, 1993.

Fuller, Ron. “The Epitaphs of Mount Holly Cemetery.” Pulaski County Historical Review 72 (Spring 2024): 13–23.

Mount Holly Cemetery. http://mounthollycemetery.org/ (accessed April 5, 2023).

Mount Holly Cemetery Association Records. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas. Finding aid online at https://cdm15728.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/findingaids/id/11108/rec/2 (accessed February 23, 2024).

Sybil Crawford Mount Holly Cemetery Research Collection. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas. Finding aid online at https://cdm15728.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/findingaids/id/12658/rec/1 (accessed February 23, 2024).

Sybil F. Crawford

Dallas, Texas

Historic Preservation

Historic Preservation Ashley Grave

Ashley Grave  Thomas Churchill Family Plot

Thomas Churchill Family Plot  Elias Conway Grave

Elias Conway Grave  Matthew Cunningham

Matthew Cunningham  Jeff Davis Gravesite

Jeff Davis Gravesite  David O. Dodd Gravesite

David O. Dodd Gravesite  Elbert English

Elbert English  Izard Grave

Izard Grave  Robert Ward Johnson Gravesite

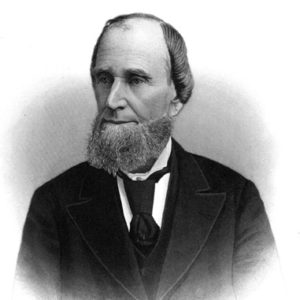

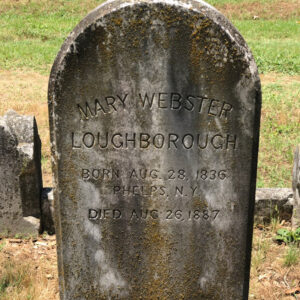

Robert Ward Johnson Gravesite  Mary Loughborough Grave

Mary Loughborough Grave  Mount Holly Cemetery

Mount Holly Cemetery  Mount Holly Cemetery

Mount Holly Cemetery  Fent Noland Grave

Fent Noland Grave  Quatie Ross Tombstone

Quatie Ross Tombstone  Ambrose Sevier Gravesite

Ambrose Sevier Gravesite  Sprague Memorial

Sprague Memorial  W. B. Worthen Gravesite

W. B. Worthen Gravesite

My grandfather, Jess Gibson, was the sexton at Mount Holly in the early 1920s. My mother was a very small child and they lived in the little house that now looks updated and converted to an office (?). My mom played around the various angels on some of the plots. She thought of them as her playmates. Nice to know this cemetery is so well cared for. Mom had happy memories there.