calsfoundation@cals.org

John Gould Fletcher (1886–1950)

John Gould Fletcher, poet and essayist, is widely acknowledged as one of the state’s most notable literary figures. He enjoyed an international reputation for much of his long career, earned the Pulitzer Prize in poetry, and participated in movements that shaped twentieth century-literature.

John Gould Fletcher was born on January 3, 1886, in Little Rock (Pulaski County) to Adolphine Krause and John G. Fletcher. After the Civil War, Fletcher’s father formed a successful cotton brokerage firm with fellow veteran Peter Hotze, bringing him wealth and prominence. Fletcher’s mother had abandoned the prospect of a musical career to tend to her ailing mother and likely centered her artistic ambitions on her only son. Fletcher was reared and educated by tutors in the company of his two sisters, Adolphine and Mary. As a child, he was rarely permitted to leave the grounds of the antebellum mansion—built by Albert Pike and purchased by the Fletchers in 1889—that was his home. Fletcher developed a dense imaginative life, nurtured by his reading of Edgar Allan Poe, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

In 1903, following a year at Phillips Andover Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, Fletcher enrolled at Harvard University. He made little progress toward his father’s goal that he would study business and law, instead adopting his mother’s assumption that artistic accomplishment was superior to mercantile success. During a 1905 train journey, the landscape of the American West inspired his first poetry. His father’s death and an estate settlement allowed Fletcher to leave Harvard without a degree and sail for Italy in 1908. The family fortune gave the poet an independent income and the freedom to write full time throughout his life, although the regular checks from a trust fund did not relieve his anxieties about his livelihood. His anxieties and sudden rages grew from his bipolar disorder, an illness marked by cyclical episodes that first erupted during his college years.

By 1913, Fletcher settled in London, where he sought the aid of Ezra Pound, the influential American poet, whom he had met earlier in Paris. Pound promoted Fletcher’s free-verse experiments to Harriet Monroe, founder of Poetry magazine, and invited Fletcher to join a group of poets that Pound had dubbed Des Imagistes. However, Fletcher resisted Pound’s attempts to revise his poems. Only when Amy Lowell, who was less dogmatic on poetic principles, supplanted Pound as the leader of the group did Fletcher agree to include his work in Imagist anthologies.

In 1914, Fletcher sailed to America. He wrote incessantly during his tour, enjoyed the critical attention given to his newly published Irradiations: Sand and Spray (1915), and relished the controversy surrounding the publication of the experimental Some Imagist Poets (1915). Fletcher returned to England to resume a liaison with the recently divorced Florence Emily “Daisy” Arbuthnot at her house in Kent. The couple married on July 5, 1916. Their marriage produced no children, but Arbuthnot’s son and daughter from her previous marriage lived with the couple.

Following the end of World War I, Amy Lowell and the other Imagist poets were surprised by the new verse Fletcher produced. His early poetry, as represented in Irradiations and Goblins and Pagodas (1916), attempted to arouse strong emotions in the reader through the sound of words rather than through their meanings. Throughout the 1920s, he crafted poems intended to shake readers from their complacency and confront a grim society corrupted by the excesses of industrialism and mass politics. Fletcher’s work, which owed much to nineteenth-century Romanticism, placed him at odds with influential modernists such as T. S. Eliot and Pound, who held that poetry should not overtly address or reflect contemporary conditions. His most significant contribution in this Romantic mode was the epic Branches of Adam (1926), which echoed the prophetic works of William Blake.

In early spring 1927, Fletcher met John Crowe Ransom, Donald Davidson, and Allen Tate while on another visit to America. These young Southerners had formed the Fugitive group of poets at Vanderbilt University but became increasingly unhappy with the direction of the industrial society. They organized the Agrarian movement to uphold the traditional hierarchy of the Old South as a better model for the good society. Fletcher eagerly enlisted in their cause, but his overwrought, anti-democratic essay on education in the Agrarian symposium, I’ll Take My Stand (1930), signaled the onset of a depressive crisis. Following a suicide attempt in late 1932 and committal at Royal Bethlehem Hospital, Fletcher permanently left his English family and took up residence in Little Rock.

Fletcher hoped that a return to a place far from centers of literary ambition would help stabilize his bipolar condition. He began to work with folklorist Vance Randolph in promoting the collection of upland folk songs and stories. Fletcher was among the first to visit and bring attention to Emma Dusenbury, the noted Mena (Polk County) folk singer. However, Fletcher remained unsettled. Within two years, he had bitterly seceded from the Agrarians and persisted in making plans to relocate from the South. His older sister and civic leader, Adolphine Fletcher Terry, now lived in the old Pike mansion and took in her wayward brother for a brief period. The prominence of the poet’s family did not keep many in his hometown from regarding him as remote and temperamental. Fletcher’s primary source of stability was the talented writer Charlie May Simon, whom he married on January 18, 1936, on the heels of the divorce from his first wife. The restless couple arranged extended stays in New York, Santa Fe, and the MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire. They traveled less frequently after moving in 1941 to the home they built on the western edge of Little Rock, a place they christened Johnswood.

Simon’s book royalties bolstered their income as Fletcher found that publishers were less willing to bring out his work. A rare opportunity came when John Netherland Heiskell of the Arkansas Gazette commissioned Fletcher to write an epic poem to commemorate the state’s centennial in 1936. A revised version of “The Story of Arkansas” later appeared in his collection, South Star (1941). Although the Arkansas poem suggested his recent allegiance to his native region, the publication of his memoir, Life is My Song, the following year concentrated on his early Imagist career.

In May 1939, Fletcher learned that he had received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for his Selected Poems (1938). He was the first Southern poet to receive the prize, although this volume was more heavily weighted toward his early free verse experiments rather than his more decidedly Southern work. Despite receipt of the prestigious award and induction into the National Institute of Arts and Letters, he did not gain a new readership. The Burning Mountain (1946), his last collection, was not widely recognized for containing vital, well-crafted poems. Arkansas (1947), his impressionistic history, served for many years as the most readable and accessible history of the state but attracted little attention elsewhere.

The knowledge that he was falling into obscurity, coupled with worsening arthritis, ignited more bouts with depression. On May 10, 1950, Fletcher drowned himself in a shallow pond near Johnswood. He is buried at Mount Holly Cemetery in Little Rock. In 1974, the John Gould Fletcher Library was opened to serve as a branch of the Central Arkansas Library System. Beginning in 1988, the University of Arkansas Press began reprinting some of the poet’s works as part of the John Gould Fletcher series.

For additional information:

Carpenter, Lucas, ed. The Autobiography of John Gould Fletcher. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1988.

———. John Gould Fletcher and Southern Modernism. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990.

Carpenter, Lucas, and Leighton Rudolph, eds. Selected Poems of John Gould Fletcher. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1988.

“John Gould Fletcher.” Character Collection, University of Arkansas at Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture. https://ualrexhibits.org/characters/confederate-ghosts-to-yankee-brahmins-jgf-1/ (accessed May 18, 2023).

Johnson, Ben F. Fierce Solitude: A Life of John Gould Fletcher. Fayetteville. University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

Rudolph, Leighton, and Ethel C. Simpson, eds. Selected Letters of John Gould Fletcher. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1996.

Stephens, Edna B. John Gould Fletcher. New York: Twayne, 1967.

Ben Johnson

Southern Arkansas University

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Literature and Authors

Literature and Authors Adolphine Krause Fletcher

Adolphine Krause Fletcher  John G. Fletcher Sr.

John G. Fletcher Sr.  John Gould Fletcher

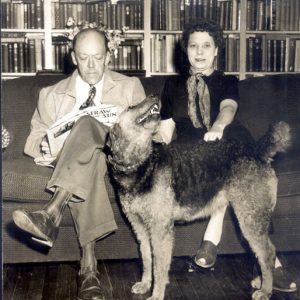

John Gould Fletcher  John Gould Fletcher and Charlie May Simon

John Gould Fletcher and Charlie May Simon  Johnswood

Johnswood

T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound cannot be characterized as poets who do not address or reflect contemporary conditions. Pound wrote explicitly about World War I in what are commonly called the Hell Cantos (Cantos 1415)–he picks up his treatment of World War I in Canto 16; his Hugh Selwyn Mauberly is one of the great anti-war poems; and Eliots The Waste Land is widely considered one of the major poems of the twentieth century because of its powerful depictions of contemporary social and spiritual conditions.

But it is true that Fletcher’s work of the 1920s shows that he was moving away from his earlier Imagist associations with Pound (Imagism being fairly radical in the mid-1910s) and toward what many would see as the more conservative cultural politics of something like I’ll Take My Stand.