calsfoundation@cals.org

Good Government Committee (Little Rock)

Little Rock (Pulaski County) business leaders formed the Good Government Committee in October 1956, which convinced the city’s voters to implement the city manager form of government in the November election. The Good Government Committee insisted the city manager system would make the municipal government more efficient and honest. Critics—mostly trade unionists and African Americans—charged that the Good Government Committee was simply a front for the Greater Little Rock Chamber of Commerce and argued that the city manager form of government would place municipal power firmly in the hands of the city’s economic elite.

On October 10, 1956, Mayor Woodrow Wilson Mann called for a vote on the city manager plan in the wake of a Pulaski County Grand Jury report that posited three things: “bossism” was rampant in the city, Mann’s administration was corrupt and inefficient, and the city manager system was needed to bring honest and efficient government to Little Rock. Although the mayor’s trade union supporters dismissed the grand jury’s report as a political hatchet job, noting that its highly publicized proceedings had not yielded a single local indictment, Mann was stung by it and called for a vote on the city manager system in the hope that its rejection would vindicate his administration.

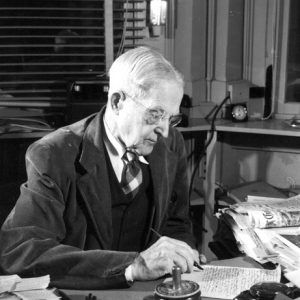

The founders of the Good Government Committee were four of the city’s most influential business leaders: J. N. Heiskell, owner and publisher of the Arkansas Gazette; August Engle, editor of the Arkansas Democrat; J. V. Satterfield, president of First National Bank and former mayor; and Stonewall Jackson Beauchamp Jr., a local businessman with close ties to Arkansas Power and Light. The four sent invitations to 200 members of the Chamber of Commerce. The 150 business leaders who showed up formally created the Good Government Committee, organized the campaign to enact the city manager system, and raised the funds necessary to conduct the fight.

Clyde Lowery, the chairman of the Good Government Committee campaign, insisted that that the city manager plan would make Little Rock’s government more efficient and less corrupt by removing political considerations from the city’s administration. The city manager plan on the ballot (detailed in Act 99 of 1921) would replace Little Rock’s mayor-aldermen system, cutting short the tenures of the mayor and city council. A seven-member board of directors, elected at large, would take the place of the ten aldermen, elected by wards, who made up the city council. Unlike the aldermen, who were paid $1,200 per year for time spent on city business, the directors would serve without compensation. The board of directors, in turn, would hire a professional city manager to carry out the duties that had been the responsibility of the elected mayor. Lowery and other city manager supporters cited the findings of the Pulaski County Grand Jury as evidence that a change was needed.

Opposition to the Good Government Committee’s campaign came from a coalition that one city manager backer described as “labor union officers, city hall politicians, and Negro factions.” Formed into the Committee for Democratic Government, opponents portrayed the push to enact the city manager form of government as little more than a power grab orchestrated by the Chamber of Commerce. Mann, who had been elected in November 1955 by a coalition of labor and black voters, called it an attempt “to overthrow democratic government.” City Attorney O. D. Longstreth portrayed the election as a fight between big business and working people. He questioned the businessmen’s enthusiasm for the city manager system, insisting that it only occurred after the election of an administration in which “labor had a chance to be heard.” Explaining that city directors would need the financial resources to win a city-wide election and work dozens of hours each week without compensation, Alderman James Griffey predicted that if the city manager system was enacted that only those from the affluent west side would have a voice in municipal governance.

With the backing of Little Rock’s two daily papers and the television stations, the Good Government Committee set the terms of the debate and transformed the election into a referendum on Mann. This was an effective strategy because Mann had alienated almost everyone in the city. His labor-friendly policies had angered the business community, his racial moderation had enraged the segregationists, and the people who had worked to elect him in the first place were put off by his call for an election on the city manager plan. Little Rock citizens made their displeasure with Mann known when they voted to implement the city manager form of government by a two-to-one margin in November.

Before the election, Good Government Committee leaders conceded that the plan they were asking voters to approve was unworkable but promised that the Arkansas General Assembly would remedy those problems after passage. When it convened in early 1957, the Arkansas General Assembly did as the Good Government Committee said it would, passing Act 8, which made several modifications—some of them significant—to the city manager plan approved by voters. In the wake of these changes, Mann argued that the plan had been altered so much by the General Assembly that another vote was needed to see if the citizens of Little Rock still approved, and he refused to set a date for the election of directors. Clyde Lowery, on behalf of the Good Government Committee, then filed suit against Mann, asking the court to order him to schedule the election. The issue remained in legal limbo until July 1, 1957, when the Arkansas Supreme Court sided with Lowery and ordered Mann to set a date for the city director election. Mann then called for the election to be held in November 1957.

On the eve of the November 1957 election, the Good Government Committee met and nominated a slate of seven candidates for the board of directors. In the midst of the Central High Crisis, the slate avoided weighing in on racial matters. This refusal to discuss race prompted segregationists to break away from the Good Government Committee and nominate a slate of their own. When the votes were counted, the Good Government Committee’s slate won six of the seven positions and took effective control of the board of directors, and Mann and other city officials left office.

Although the Good Government Committee hoped to continue after the 1957 election and play a continuing role in municipal politics, its influence quickly waned. The controversies growing out of the Central High crisis made it difficult for the Good Government Committee to maintain the unity that had enabled it to transform the municipal structure.

For additional information:

Bentley, George. “Jury Calls for Purge of City Hall Bosses.” Arkansas Gazette, September 22, 1956, pp. 1A, 2A.

Burnham, Ron. “City Manager Plan Wins by Large Margin.” Arkansas Democrat, November 7, 1956, p. 1.

———. “Mayor Calls for Vote on City Manager Plan in Surprise Move.” Arkansas Democrat, October 10, 1956, p. 1.

“City Manager Note.” Arkansas Recorder, October 26, 1956, p. 2.

Elizabeth Jacoway Little Rock Crisis Collection. CALS Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

“It’s the Manager Plan 2 to 1.” Arkansas Gazette, November 7, 1956, p. 1A.

Jacoway, Elizabeth. “Taken by Surprise: Little Rock Business Leaders and Desegregation.” In Southern Businessmen and Desegregation, edited by Elizabeth Jacoway and David R. Colburn. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1982.

———. Turn Away Thy Son: Little Rock, the Crisis that Shocked the Nation. New York: Free Press, 2007.

Mann v. Lowry, 227 Ark. 1132 (1957).

Pierce, Michael. “The City Manager System and the Collapse of Racial Moderation in Little Rock, 1955–1957.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly (Summer 2019): 166–205.

———. “Revenge of the Elite: The City Manager System and the Collapse of Racial Moderation in Little Rock, 1955–1957.” Arkansas Times, March 2019, pp. 67–75. Online at https://www.arktimes.com/arkansas/revenge-of-the-elite-in-little-rock/Content?oid=28592759 (accessed March 4, 2019).

Spitzburg, Irving, Jr. Racial Politics in Little Rock, 1954–1964. New York: Garland, 1987.

“Text of Jury’s Report.” Arkansas Gazette, September 22, 1956, p. 3A.

Touhey, Matilda. “Manager Plan Foes, Pros Trade Blows.” Arkansas Gazette, November 5, 1956, pp. 1A, 2A.

Valachovic, Ernest. “Civic Leaders Start Action to Back City Manager Plan.” Arkansas Gazette, October 23, 1956, pp. 1A, 2A.

Michael Pierce

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.