calsfoundation@cals.org

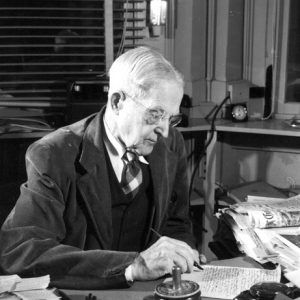

John Netherland Heiskell (1872–1972)

aka: J. N. Heiskell

John Netherland (J. N.) Heiskell served as editor of the Arkansas Gazette for more than seventy years. During his tenure, he headed the newspaper during two world wars, the Roaring Twenties, the Great Depression, the civil rights movement, the war in Vietnam, and thousands of other events. He was an active civic affairs activist and used his influence to guide the state through decades of change.

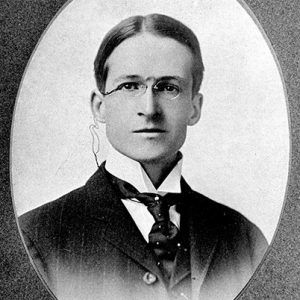

J. N. Heiskell was born on November 2, 1872, in Rogersville, Tennessee, to Carrick White Heiskell and Eliza Ayre Netherland Heiskell. He was the elder of two sons. Heiskell’s father—a former Confederate officer, lawyer, and later a judge—moved the family to Memphis shortly after the Civil War. Heiskell, whom his family and friends called Ned, was a bookish youth who preferred reading the encyclopedia to novels. He entered the University of Tennessee at Knoxville before his eighteenth birthday and graduated in three years at the head of his class on June 7, 1893. At the university, Heiskell studied languages, mathematics, and physics, but his true interest was in journalism, an area in which the university had no formal curriculum.

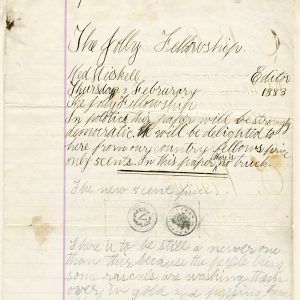

His early journalism career included jobs with newspapers in Knoxville and Memphis and with the Associated Press in Chicago and Louisville. On June 17, 1902, Heiskell’s family bought controlling interest in the Arkansas Gazette. Heiskell became the editor, and his brother, Fred, became managing editor.

Under the Heiskell brothers’ leadership and editorial direction, circulation nearly doubled in four years. Heiskell kept the Gazette neutral in Democratic primary contests and faithfully supported Democratic candidates against the Republicans. Though he generally avoided political fights, in 1903, Heiskell got into a long-term editorial battle with the state’s most powerful Democratic officeholder, Governor Jeff Davis, after Davis branded the Gazette “a Republican sheet” and implied it was subsidized financially by outsiders. Heiskell asserted that Davis had lied and that the real reason the governor was upset was because the newspaper had published embarrassing aspects of his record and would not do his bidding.

In an ironic twist, Governor George Donaghey later chose Heiskell to succeed Davis in the United States Senate after Davis’s death in office. Heiskell served from January 6, 1913, until January 29, 1913, when a successor was elected.

On June 28, 1910, Heiskell married Wilhelmina Mann, daughter of the nationally prominent architect, George R. Mann. The couple had four children: Elizabeth, Louise, John N. Jr., and Carrick.

A reserved, sometimes shy, and polite man, Heiskell was non-confrontational and generally left most of the unpleasant tasks of daily newspapering to a series of tough sub-editors. His carefully constructed editorials avoided personal attacks and focused on issues. He was quick to defend the state against outside criticism. However, his shy nature did not deter him from speaking out from the editorial page and becoming active in civic affairs. In 1907, he joined a successful effort to build the city’s first public library. He served on the library board from that year until his death and was issued the first library card.

Heiskell’s editorial opinions ranged widely: for city planning and the commission form of city government, against the Little Rock School Board’s decision to drop German from its curriculum during World War I, for curbs on immigration so that newly arrived foreigners could be more easily assimilated, and against anti-Semitism. His editorials defended conventional morality and supported Prohibition. Under Heiskell, the Gazette’s editorials supported laws and other measures to bolster racial segregation under the “separate but equal” theory. They were paternalistic toward African Americans, urging them to trust in white leaders to further their interests. At the same time, he waged a long campaign against lynching and called for a grand jury investigation into the breakdown of Little Rock (Pulaski County) law enforcement during racially motivated mob violence against John Carter in 1927.

Gazette staff members recall Heiskell as a man of formal bearing and dry wit. His personal memory stretched back to the end of Reconstruction, and he was an avid reader and collector of Arkansas history materials. Heiskell’s personal collection of Arkansiana was housed at the newspaper, and during the 1950s, the Gazette was believed to be the only newspaper in the country with a full-time staff historian.

Heiskell’s eldest son died during childhood, and his younger son died while flying for the Air Transport Command in the Himalayas during World War II. In his seventies, and with no male heir to carry on for him, Heiskell had to look elsewhere for continued leadership for the newspaper. In 1945, he began the search for his successor and, in 1947, chose Harry S. Ashmore, a reform-minded Southerner and rising star in American journalism, to head the editorial page. Heiskell’s daughter, Louise, married Hugh B. Patterson Jr., an Army major who had worked in commercial printing before the war. Patterson became the advertising manager for the Gazette.

After expanding Ashmore’s role to executive editor and Patterson’s role to publisher, Heiskell was able to leave most of the responsibility for the newspaper to the younger men. However, he retained the title of editor and continued to come to the office daily. When the desegregation of Little Rock’s Central High School began in 1957, Heiskell supported Ashmore and Patterson’s stand for law and order and obedience to the federal courts. The resulting editorials written by Ashmore and the newspaper’s coverage of the desegregation crisis won two Pulitzer Prizes and several other awards. In 1961, Heiskell was one of the charter members of the Arkansas Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists.

Although Heiskell stopped going to the office at age ninety-nine, he continued to take an active interest in the newspaper. He began by having a copy of the newspaper delivered to his home by messenger as soon as it came off the press each night. Eventually, he switched to having his secretary call him daily at his home and read the entire newspaper to him. He operated on the premise that “anyone who runs a newspaper needs to know what’s in it, even to the classified ads.”

Heiskell died of congestive heart failure brought on by arteriosclerosis on December 28, 1972. He is buried in Little Rock’s Mount Holly Cemetery.

For additional information:

A Gazette Staff Tribute to J. N. Heiskell. Supplement to the Arkansas Gazette. November 2, 1972.

Heiskell Family Papers. Center for Arkansas History and Culture. University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Reed, Roy, ed. Looking Back at the Arkansas Gazette: An Oral History. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2009.

Rutherford, William K., Jr. “Arkansas Gazette Editor J. N. Heiskell: Heart and Mind.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 1987.

Stephens, Donna Lampkin. “The Conscience of the Arkansas Gazette.” Journalism History 38 (Spring 2012): 34–42.

Thompson, John A. “An Ambition Achieved: J. N. Heiskell Becomes Editor of the Arkansas Gazette.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 46 (Summer 1987): 156–166.

———. “Gentleman Editor: Mr. Heiskell of the Gazette. The Early Years: 1902–1922.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 1983.

Nathania Sawyer

CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

John Thompson

North Little Rock, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.