calsfoundation@cals.org

Southern Cotton Oil Mill Strike

On December 17, 1945, 117 of the 125 mostly African-American employees of the Southern Cotton Oil Mill Company in Little Rock (Pulaski County) walked off the job, demanding sixty cents an hour and time and a half for anything over forty hours a week. The strikers—members of Food, Tobacco, Agricultural and Allied Workers (FTA) Local 98—set up picket lines, and the company ceased milling operations, although it did maintain a small workforce to receive shipments and maintain equipment. The strike remained peaceful until December 26, when an African-American strikebreaker named Otha Williams killed a striker, Walter Campbell, also an African American. A Pulaski County grand jury, empaneled by County Prosecutor Sam Robinson, refused to indict Williams on charges of murder or manslaughter, declaring that he had acted in self-defense. Robinson did, however, secure indictments against five members of the FTA Local 98 for their involvement in the incident. The men were charged with violating the Anti-Labor Violence Act, which the Arkansas General Assembly passed in 1943 amidst widespread fears that Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) unions—especially FTA predecessors such as the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU) and United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing, and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA)— would organize black workers and challenge Jim Crow labor systems. The statute made strikers—but not strikebreakers or employers—criminally liable for any violence that occurred during labor disputes. The convictions of the FTA members under this statute and subsequent appeals helped realign Arkansas politics, bringing black activists and union leaders into a de facto alliance pitted against the planters and industrialists committed to retaining the Jim Crow status quo.

Little Rock’s Southern Cotton Oil Mill, a subsidiary of an international corporation that made Wesson cooking oil and Snowdrift shortening, and UCAPAWA first signed a contract in 1941 and agreed to a second contract during World War II. The second contract, which provided fifty cents an hour with no overtime provisions, expired in the summer of 1945, and the parties entered into negotiations. The plant’s manager refused to consider any change in the contract. U.S. Conciliation Service tried to mediate the dispute but got nowhere. The FTA offered to submit the dispute to an independent arbitrator, but the company refused. With collective bargaining at an impasse, the employees went on strike.

When the Southern Cotton Oil Mill employees began the strike on December 17, 1945, they were aware of the Anti-Labor Violence Act. The local counseled the men about the law and allowed only long-time employees with families to walk the picket line. There were no incidents until Otha Williams killed Walter Campbell on the day after Christmas. Two distinct narratives of the incident quickly emerged. According to Prosecutor Robinson and supporters of the Southern Cotton Oil Mill, Williams and four other strikebreakers were leaving the mill when Campbell and another striker, Robert Brooks, set upon them with sticks at the behest of strike leaders. Williams pulled a knife and killed Campbell in self-defense. Local 98 and its supporters, however, argued that Campbell and Brooks, who were a block away from the mill and not on picket duty, had been set up, and that the five strikebreakers attacked the two strikers.

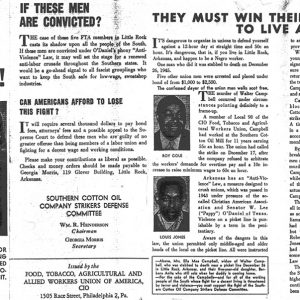

The indictment of the five members of FTA Local 98—Lewis Jones, chairman of the local’s committee at the Southern Cotton Oil Mill; Roy Cole, assistant chairman of plant committee; Jessie Bean; Robert Brooks; and Bishop Jackson—spurred the mobilization of both pro-union and anti-union forces. The local set up the Southern Cotton Oil Mill Workers Defense Committee to solicit funds from around the country to finance the legal defense. Conservative businessmen and planters formed the Arkansas Free Enterprise Association, which pledged to aid in the prosecution of the Southern Cotton Oil Mill strikers and, more generally, fight the state’s growing labor movement.

By the time the trial got under way in March 1946, charges had been dropped against Brooks and Jackson, with the prosecution focusing on Local 98’s leadership at the mill. The judge, Lawrence Auten, appointed a prominent member of the Arkansas Free Enterprise Association to choose potential jurors. The prosecution and defense presented their competing narratives of events and brought in witnesses to substantiate key points. In the end, the jury dismissed the defense’s narrative and evidence, concluding that the prosecution had proven its case beyond a reasonable doubt. The judge sentenced Lewis Jones, Roy Cole, and Jessie Bean each to a year of hard labor.

The outcry was immediate. The black community rallied to protest the convictions, and labor unions solicited funds for an appeal. The most outspoken critics were Daisy and L. C. Bates, publishers of the black newspaper the Arkansas State Press. The paper’s front-page headline read “FTA Strikers Sentenced to Pen by Handpicked Jury.” The accompanying article began, “Three strikers, who by all observation were guilty of no greater crime than walking a picket line, were sentenced to one year in the penitentiary yesterday by a ‘hand-picked’ jury, while a scab who killed a striker is free.” Judge Auten was so angered by the Arkansas State Press’s coverage that he found the Bateses in contempt of court and sentenced each of them to ten days in jail and a $100 fine. The Arkansas Supreme Court later vacated the contempt convictions, finding the convictions to be in violation of the state constitution’s guarantee of “liberty of the press.”

In the fall of 1946, the Arkansas Supreme Court ordered a new trial for Jones, Cole, and Bean on the grounds that the judge had allowed improper testimony. The ongoing dispute over the Southern Cotton Oil Mill strikers as well as broader concerns about the Anti-Labor Violence Act, so called right-to-work laws, and the CIO unions became the defining issues in 1946 elections throughout the state. In Pulaski County, the Arkansas Free Enterprise Association and other antiunion forces rallied on behalf of Sam Robinson’s campaign to be reelected county prosecutor. Blacks and labor got behind his opponent, State Representative Edwin Dunaway. Dunaway won the prosecutor’s job, but antiunion forces made headway in other areas of the state. Neither side won a clear victory. Two years later, Arkansas elections were still defined by debates over labor and civil rights. The Arkansas Free Enterprise Association ran the Dixiecrat campaign, while labor and black voters coalesced behind the gubernatorial campaign of Sidney McMath.

In the retrial, a Pulaski County jury again found the three men guilty. The trade unionists, with funds from the CIO and the black community, launched a series of appeals. The Arkansas Supreme Court heard the case on two more occasions, and the U.S. Supreme Court twice refused to vacate the convictions; it did, however, order the case back to state court for further adjudication. Appeals were ongoing. On his last day in office, December 31, 1952, Governor McMath pardoned the men, ending the legal struggle more than seven years after Otha Williams killed Walter Campbell.

For additional information:

Bates, Daisy. The Long Shadow of Little Rock: A Memoir. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1986.

Bates, L. C. “All Victories Have to Be Paid For.” Southern Patriot (February 1950): 2.

Cole, Jones and Bean v. State (1946), 210 Ark. 433 (Case No. 4414), Arkansas Supreme Court Case File, Bowen Law Library. University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Cole, Jones and Bean v. State (1947), 211 Ark. 836 (Case No. 4448), Arkansas Supreme Court Case File, Bowen Law Library. University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law, Little Rock, Arkansas.

“Cotton Oil Mill Closed By Strike.” Arkansas Gazette, December 18, 1945, p. 5.

Fletcher, John L. “Labor and Management to Fight It Out.” Arkansas Gazette, June 16, 1946, pp. 1, 4.

“McMath Grants 3 pardons, Last Official Act.” Fort Smith Union News, January 22, 1953, pp. 1, 3.

“Nation Focuses Attention on Arkansas Voting: Labor Issue and Negro Balloting Closely Watched.” Arkansas Democrat, July 28, 1946, pp. 1–2.

“Strike Picket Slain In Fight Near Oil Mill.” Arkansas Gazette, December 27, 1945, p. 1.

Michael Pierce

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Business, Commerce, and Industry

Business, Commerce, and Industry World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967 FTA Pamphlet

FTA Pamphlet  Southern Cotton Oil Mill Strike

Southern Cotton Oil Mill Strike

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.