calsfoundation@cals.org

Labor Movement

Soon after Arkansas’s 1836 admission to the Union, wage workers in the state began uniting for their mutual economic and political benefit. Throughout the nineteenth century, these associations—commonly called trade unions—tended to be short lived and unstable, reflecting the dominance of agriculture in Arkansas’s economy. But in the twentieth century, as industry began gaining a toehold in the state, the labor movement began improving the lives of wage workers through collective bargaining and by securing passage of legislation in the interest of all workers. Although weak when compared with their counterparts in more industrialized states, Arkansas’s trade unions were at the forefront of every significant wave of reform in the state during the twentieth century—the Progressive Era, the New Deal, and the 1960s.

The first known gathering of an association of Arkansas workers occurred on December 7, 1839, when a group of men calling themselves “the mechanics of Little Rock” held a public meeting at which they endorsed a slate of political candidates. This association appears to have been temporary, but, less than two years later, Little Rock (Pulaski County) workers attempted to form a permanent organization called the Mechanics Institute. A committee drafted rules for the new organization in March 1841 and scheduled meetings, but it is unclear how long this organization survived.

Little Rock’s working men created a more stable organization in June 1845 when a group of carpenters, millwrights, bricklayers, and other artisans came together in the Mechanics Association of Little Rock. The association sought to protect the workers from competition from convict labor through political action—lobbying the legislature, offering resolutions, and canvassing candidates. But it failed to eliminate the problem. In fact, the fight against prison labor continued to occupy Arkansas’s labor movement into the twentieth century.

The Mechanics Association achieved its only success in late 1858. Earlier that year, it had called on the Arkansas General Assembly to prohibit slave owners from training their slaves as mechanics and putting them in competition with white labor and to evict free blacks—many of whom were competing with white workers—from the state. The first proposal proved to be unpopular among the slaveholders who dominated the legislature, but the second found widespread support. In February 1859, the General Assembly passed Act 151, ordering free blacks to leave the state by January 1, 1860. After the passage of the law, the Mechanics Association began to break up slowly.

The earliest known attempt to organize workers along craft lines occurred in September 1856 when Little Rock’s journeymen printers formed a union. The organization did not last long, for in 1861 the printers again attempted to establish an association for “protection and contributory benefits.” That organization apparently did not take, because, in July 1865, they tried once more. This attempt proved more successful. The union received a charter from the International Typographical Union and operated into the twenty-first century. While the Mechanics Association had represented workers in the political arena, craft unions concentrated on improving the lives of members through collective bargaining—increasing pay, improving working conditions, and limiting those entering the trade through apprenticeship systems.

Arkansas witnessed a proliferation of craft unions following the Civil War—wagon makers in Russellville (Pope County); agricultural laborers in Pulaski, Phillips, and Ouachita counties; washer women in Little Rock; and carpenters and bricklayers throughout the state. Periodically, a town’s craft unions would form local federations to mobilize voters and lobby officials, but these federations—except for ones in Little Rock and Fort Smith (Sebastian County)—usually proved ineffectual. Except for periodic efforts to eliminate prison labor, Arkansas’s labor movement shied away from statewide political action, relying instead on skill and collective bargaining.

That changed in the mid-1880s with the arrival of the Knights of Labor in Arkansas. Formed in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1869, the Knights sought to unite all producers of wealth regardless of craft, race, or gender to fight against the emerging “wage system”—conditions that caused workers to labor for wages their entire lives rather than gaining economic independence. A secret organization until 1882, the Knights grew rapidly around the nation and in Arkansas after striking railroaders won concessions from Jay Gould’s Southwestern System in 1885. Although the state’s railroaders did not take part in that strike, by 1886, the Knights boasted nearly 3,000 members in Arkansas, mostly in towns along major railroads—Little Rock, Malvern (Hot Spring County), Prescott (Nevada County), Waldron (Scott County), and Pine Bluff (Jefferson County). That year proved to be the high-water mark for the Knights nationally as the failure of another strike against Gould’s Southwestern System (this one included Arkansas Knights) and 1887’s Haymarket Riot led to a sharp decline in membership. But in Arkansas, membership continued to grow. The addition of coal miners in the western part of the state, black agricultural workers in Woodruff and St. Francis counties, and other workers raised membership to almost 5,400.

Although the Knights remained officially non-partisan, the group’s leaders in Arkansas joined the leaders of the Agricultural Wheel in the Union Labor Party (ULP) in 1888. Calling for regulation of mines and trusts, the elimination of convict labor, currency and bank reform, and the expansion of the state’s education system, the ULP worked closely with the Republicans that year, nearly beating the Democrats in an election marked by rampant fraud and intimidation. The association of the Knights with the ULP alienated some members, and membership fell to 3,035 in 1888. The Knights continued to be active among black agricultural workers in eastern Arkansas, but the murder and repression that accompanied the 1891 cotton pickers’ strike contributed to further decline. The death of the Knights in Arkansas ultimately came at the hands of its erstwhile ally, the Farmers’ Alliance, which raided the Knights for members.

In 1898, the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) began organizing coal miners in western Arkansas, and, by 1903, every miner in Arkansas belonged to the union and dug coal in mines operating under union contracts. The UMWA would become the most powerful union in early twentieth-century Arkansas.

The UMWA took the lead in the establishment of the Arkansas State Federation of Labor (ASFL) in 1904. That year, over 100 delegates from urban labor federations and craft unions declared that a “struggle is going on in all nations of the world between the capitalist and the laborer which grows in intensity from year to year and will work disastrous results on the toiling millions if they do not combine for mutual protection and benefit.” The federation, which affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL), sought to unite the state’s trade unionists for political action—endorsing sympathetic candidates and lobbying the legislature. Delegates elected S. F. Brackney, a UMWA official from Sebastian County, as president and L. H. Moore of Little Rock as secretary. Unlike most labor organizations, the ASFL did not establish a color line and included black unions, white unions, and biracial unions like the UMWA. The first convention even elected N. M. Thomas, a black carpenter from Pine Bluff, to a vice presidency.

The ASFL was an immediate success, becoming a principal architect of the Progressive movement in Arkansas. Working closely with the State Farmers Union, it convinced the legislature to enact a minimum wage for women, restrict child labor, regulate prison labor, prohibit blacklisting of union members, ban the payment of wages in scrip, and establish the Arkansas Bureau of Labor and Statistics. It also led the fight for a number of reforms focusing on life outside of the workplace—the initiative and referendum, women’s suffrage, and improvements in the education system.

The success of Arkansas’s labor movement provoked reactions among some employers, landowners, and civic leaders that often led to violence and death. In 1914, a southern Sebastian County coal operator abrogated a contract with the UMWA and imported replacement workers and armed guards to protect them, setting off a series of conflicts that spurred a handful of deaths, the prosecution of union officials, and a U.S. Supreme Court decision, Coronado Coal Co. v. United Mine Workers of America, that expanded the scope of legislation Congress could enact under the interstate commerce clause. In Harrison (Boone County), civic leaders in partnership with the Ku Klux Klan hanged a striking railroader from a bridge in 1923 and marched nearly 200 strikers to the Missouri line under threat of violence in what is now called the Harrison Railroad Riot. Most infamously, Phillips County landowners responded to the formation of a sharecroppers’ union, the Progressive Farmers and Household Union, by launching an attack, now called the Elaine Massacre, that saw as many as 400 African Americans killed in 1919 (though the number murdered remains in dispute).

This employer counter-offensive left Arkansas’s labor movement in tatters. The UMWA and the railroad unions were rendered ineffective—forced to accept wages and conditions dictated by employers. Only trade unions composed of highly skilled men—typographers, carpenters, masons, and machinists—retained enough power to protect members.

President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal to combat the Great Depression gave a boost to the labor movement. The National Industrial Recovery Act (1933) and the National Labor Relations Act (1935) promised federal protection to industrial workers who organized labor unions and required that companies bargain with such unions in good faith. In the coal fields and train yards of Arkansas, workers revived their unions. Workers also organized new unions throughout the state—paper mill workers in Crossett (Ashley County), furniture workers in Fort Smith, chemical and oil workers in El Dorado (Union County), and state and local employees in Little Rock. The number of organized workers in the state reached 25,000 by 1939.

The New Deal’s Agricultural Adjustment Act paid farmers to reduce the amount of acreage under cultivation. In the cotton areas of eastern Arkansas, landowners were reluctant to follow the program’s requirement that payments be shared with tenant farmers and sharecroppers. To demand their share of these payments and improve conditions, eleven white men and seven black men formed the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union (STFU) in Poinsett County in July 1934. The union quickly spread throughout Arkansas. Leaders of the STFU, one of the few interracial unions, boasted a membership of 25,000 in Arkansas. At the behest of lawmakers from agricultural states, the National Labor Relations Act and other New Deal labor legislation explicitly excluded agricultural workers from the protections offered to industrial workers. Without federal support, the STFU proved unable to survive the harassment of landowners and local officials, as well as internal ideological disputes. By 1939, the STFU only operated in two Arkansas counties.

Empowered by the rising membership rolls, the ASFL launched successful campaigns to create unemployment and workmen’s compensation programs. The ASFL led the coalition that crafted Arkansas’s unemployment compensation plan in 1937, an effort encouraged by federal law. The next year, an ASFL initiative campaign created Arkansas’s workmen’s compensation program.

Arguments over how best to organize workers rushing into trade unions in the 1930s produced a split in the nation’s labor movement. Some labor leaders argued that workers should be organized along industrial lines (i.e., the workers in one industry should join the same union). Within the AFL, industrial unionists formed the Committee on Industrial Organization—later the Congress on Industrial Organization (CIO)—to organize those laboring in mass production industries. Other leaders wanted to organize workers along craft lines. The conflict came to a head in late 1936 when the AFL expelled unions associated with the CIO. In 1937, the ASFL followed suit, kicking out those unions associated with industrial unionism. Arkansas’s CIO unions quickly formed a statewide federation, the Arkansas Industrial Council (AIC), to mirror the ASFL. By 1939, the Fort Smith–based AIC represented 5,400 workers, including coal miners, paper and cotton millhands, furniture makers, and glass workers.

The success of the Arkansas labor movement, especially the unions associated with the CIO, whose leaders publicly advocated racial equality, provoked a reaction among landowners and segments of the business community in the 1930s and early 1940s. In 1943, the Christian American Association (CAA) convinced the legislature to make it a felony to use force or threats of violence to prevent individuals “from engaging in any legal vocation of their choice.” This measure had the potential to transform picketing into a felony—strikebreakers could claim that the mere presence of picketers constituted a threat of violence. The next year, the CAA joined with Arkansas Free Enterprise Association to circulate petitions to enact a law forbidding labor unions and companies from signing agreements requiring union membership as a condition of employment. The state’s voters approved the so-called “Right to Work” initiative in the fall, 105,300 to 87,652.

The industrial expansion that accompanied World War II and the postwar years provided a boost to Arkansas’s labor movement. Between 1939 and 1944, union membership went from 25,000 to 43,300. Membership would continue to grow after the war, reaching 75,000 by 1955. This growth increased the political power of trade unionists, especially in manufacturing centers like Little Rock, Fort Smith, and El Dorado.

The strength of Arkansas labor was further enhanced when the ASFL and AIC united in March 1956. The AFL and the CIO merged in December 1955, and the unified organization called for state affiliates to do likewise. Arkansas, in fact, was the first state to have its federations merge. The new organization, which styled itself the Arkansas State Federated Labor Council (later the Arkansas AFL-CIO), set out an ambitious legislative agenda to improve the lives of workers, both the organized and the unorganized: increase of workmen’s compensation and unemployment benefits, revocation of legislation forbidding unions and employers from agreeing to closed shops, collective bargaining for public sector and intrastate workers, passing of prevailing wage laws, and improvements in education. The biggest obstacle to the enactment of labor’s agenda, according to its leaders, was the existence of the poll tax, which robbed wage earners of political power and made it possible for wealthy planters to vote for scores of their tenants and sharecroppers. Led by President Odell Smith, the federation helped place an initiative on the ballot in 1956 to repeal the state’s poll tax, but, amid the heightened racial tension over school integration, the campaign fell short.

In the 1960s, union rolls continued to grow, and by 1964, fifteen percent of the state’s nonagricultural workers—some 85,000 Arkansans—belonged to trade unions. About 25,000 of those union members belonged to unions affiliated with the Arkansas AFL-CIO, which under the leadership of J. Bill Becker became one of the state’s most effective political players. The labor movement took the lead in the creation of a liberal coalition that convinced the General Assembly to pass measures that helped all workers regardless of union affiliation: increases in workers’ compensation and unemployment benefits, replacement of the poll tax with a voter registration system, and passage of a minimum wage law. There were limits to labor’s power, however, especially when it came to the enactment of legislation that specifically benefited unions. The Arkansas AFL-CIO proved unable to muster the support needed to rid the state of its “right-to-work” law or pass legislation extending collective bargaining rights to public employees.

The labor movement’s power in Arkansas peaked in the 1960s. Following national trends, the percentage of Arkansas workers belonging to unions began dropping as foreign competition, the collapse of the Democratic Party’s New Deal coalition, and the emergence of anti-union or non-union companies such as Walmart Inc. and J. B. Hunt took their toll. By 2006, only 5.1 percent of non-agricultural workers in Arkansas belonged to unions, placing the state ahead of only five states in terms of union density. The Republican Party’s takeover of all statewide offices and the state legislature, complete with the election of 2014, increased the repression of unions in the state. For example, the state takeover of the Little Rock School District in 2015 was regarded by many as an attack upon teacher’s unions in the capital city. In 2021, the legislature passed, and Governor Asa Hutchinson signed, Act 612, which would bar many public employees from participating in collective bargaining through a union; exceptions were carved out for more conservative-leaning unions, such as those representing police offices and firefighters. In 2023, Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders signed Act 195, eliminating the requirement that minors under the age of sixteen verify their age and receive the written consent of a parent or guardian before being employed. Opponents of the bill argued that it would increase the potential of vulnerable children being exploited, and Sanders’s signing of the bill came after Packers Sanitation Services, a food sanitation company with facilities in Arkansas, was fined for employing children between ages thirteen and seventeen in hazardous conditions.

For additional information:

Arkansas Labor Collection. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Arkansas State AFL-CIO. Program of Progress for Arkansas. Little Rock: Arkansas State AFL-CIO, 1962.

Atkins, Joseph B. Covering for the Bosses: Labor and the Southern Press. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2008.

Babcock, Bernie. “Trade Unions in Arkansas.” Union Labor Bulletin. July 10, 1936, pp. 2–5.

Biegert, M. Langley. “Legacy of Resistance: Uncovering the History of Collective Action by Black Agricultural Workers in Central East Arkansas from the 1860s to the 1930s.” Journal of Social History 32 (Autumn 1998): 73–99.

Blevins, Brooks R. “The Strike and the Still: Anti-Radical Violence and the Ku Klux Klan in the Ozarks.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 52 (Winter 1993): 405–426.

Coronado Coal Co. et al. v. United Mine Workers of America et al., 268 U.S. 295; 45 S. Ct. 551; 69 L. Ed. 963 (1925). Online at http://supreme.justia.com/us/268/295/case.html (accessed September 7, 2020).

Cullison, William Eugene. “An Examination of Union Membership in Arkansas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma.” PhD diss., University of Oklahoma, 1967.

Feight, Patrick. “From Picketers to Entrepreneurs: Labor Dispute Leads to Union Furniture Business Venture.” Journal of the Fort Smith Historical Society 36 (April 2012): 32–36.

Gall, Gilbert J. “Southern Industrial Workers and Anti-Union Sentiment: Arkansas and Florida in 1944.” In Organized Labor in the Twentieth-Century South, edited by Robert H. Zieger. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1991.

Gellman, Eric, and Jarod Roll. The Gospel of the Working Class: Labor’s Southern Prophets in New Deal America. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2011.

Grubbs, Donald H. Cry from the Cotton: The Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union and the New Deal. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1971.

Haiken, Elizabeth. “‘The Lord Helps Those Who Help Themselves’: Black Laundresses in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1917–1921.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 49 (Spring 1990): 20–50.

Halpern, Martin. “Arkansas and the Defeat of Labor Law Reform in 1978 and 1994.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 57 (Spring 1998): 99–133.

Hild, Matthew. Arkansas’s Gilded Age: The Rise, Decline, and Legacy of Populism and Working-Class Protest. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2018.

———. Greenbackers, Knights of Labor, and Populists: Farmer-Labor Insurgency in the Late-Nineteenth-Century South. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2007.

Holmes, William F. “The Arkansas Cotton Pickers Strike of 1891 and the Demise of the Colored Farmers’ Alliance.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 32 (Summer 1973): 107–119.

Lewis, Suzanne S. “The Wheelbarrow Strike of 1915: Union Solidarity in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 43 (Autumn 1984): 208–221.

Little Rock Typographical Union No. 92, Souvenir of the 100th Anniversary Celebration, 1865–1965, Hotel Marion, Little Rock, Ark., January 8–9, 1966. Little Rock: Allied Printers, 1966.

“Merger Convention of the Arkansas State Federated Labor Council, March 20–21, 1956.” Little Rock: 1956.

Minchin, Timothy J. “Torn Apart: Permanent Replacements and the Crossett Strike of 1985.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 56 (Spring 2000): 31–58.

Mitchell, H. L. Roll the Union On: A Pictorial History of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union. Chicago: Charles Kerr, 1987.

Moyers, David B. “Trouble in a Company Town: The Crossett Strike of 1940.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 48 (Spring 1989): 34–56.

Pierce, Michael. “Great Women All, Serving a Glorious Cause: Freda Hogan Ameringer’s Reminiscences of Socialism in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 69 (Winter 2010): 293–324.

———. “John McClellan, the Teamsters, and Biracial Labor Politics in Arkansas, 1947–1959.” In Life and Labor in the New South, edited by Robert H. Zeiger. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2012.

———. “The Mechanics of Labor: Free Labor Ideas in Antebellum Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 67 (Autumn 2008): 221–244.

———. “Odell Smith, Teamsters Local 878, and Civil Rights Unionism in Little Rock, 1943–1965.” Journal of Southern History 84 (November 2018): 925–958.

———. “Orval Faubus and the Rise of Anti-Labor Populism in Northwestern Arkansas.” In The Right and Labor in America: Politics, Ideology, and Imagination, edited by Nelson Lichtenstein and Elizabeth Tandy Shermer. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012.

Pierce, Michael, and Calvin White, eds. Race, Labor, and Violence in the Delta: Essays to Mark the Centennial of the Elaine Massacre. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2022.

Quincin, Ashley. “Arkansas Advocates Voice Concern as State Weakens Child Labor Protections.” Facing South, July 20, 2023. https://www.facingsouth.org/arkansas-weakens-child-labor-protections-sarah-sanders (accessed December 20, 2023).

Ray, Victor K. “The Role of Labor Unions.” In Arkansas: Colony and State, edited by Leland DuVall. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1969.

Schmidt, Kyra. “Hello Girls on Strike: Telephone Operators, the Fort Smith General Strike and the Struggle for Democracy in Great War Arkansas.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2020.

Turner, Ralph, and William Rogers. “Arkansas Labor in Revolt: Little Rock and the Great Southwestern Strike.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 24 (Spring 1965): 29–46.

Sizer, Samuel A. “‘This is Union Man’s Country’: Sebastian County, 1914.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 27 (Winter 1968): 306–329.

Michael Pierce

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

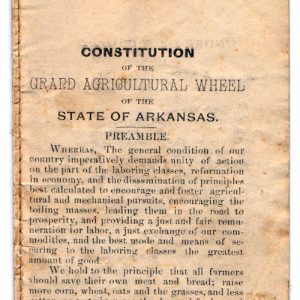

Agricultural Wheel Constitution

Agricultural Wheel Constitution  Arkansas City Cotton Picker

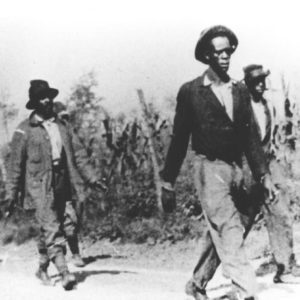

Arkansas City Cotton Picker  Crossett Strike

Crossett Strike  Elaine Massacre Prisoners

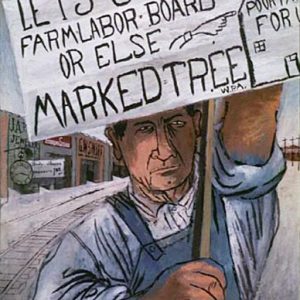

Elaine Massacre Prisoners  Lest We Forget by Ben Shahn

Lest We Forget by Ben Shahn  Limedale Plant Strike

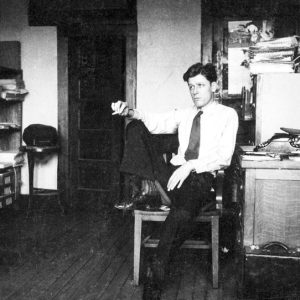

Limedale Plant Strike  Harry Mitchell

Harry Mitchell  Southern Tenant Farmers' Union

Southern Tenant Farmers' Union

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.