calsfoundation@cals.org

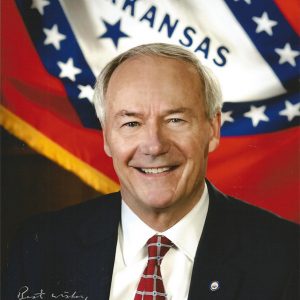

Asa Hutchinson (1950–)

aka: William Asa Hutchinson

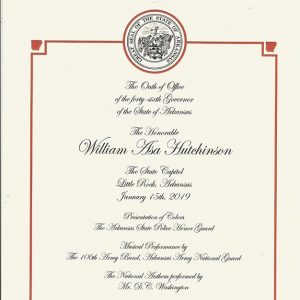

Forty-sixth Governor (2015–2023)

William Asa Hutchinson first gained national attention as the youngest district attorney in the nation in 1982. He went on to represent the Third District of Arkansas in Congress as a Republican from 1997 to 2001, resigning his post on August 6, 2001, to become the director of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). Hutchinson left the DEA to become the Under Secretary for Border and Transportation Security at the Department of Homeland Security, a post he held from 2003 to 2005. In 2005, Hutchinson began actively campaigning for the governorship of Arkansas but lost the race to Mike Beebe in November 2006. However, he was elected governor eight years later in 2014 and reelected in 2018.

Asa Hutchinson was born on December 3, 1950, in Bentonville (Benton County) to John Malcom Sr. and Coral Hutchinson. John Malcom Hutchinson Sr. was a grocer, farmer, and eventually mayor of Sulphur Springs (Benton County). Hutchinson was the youngest of six children. He attended grade school in Gravette (Benton County) and graduated from Springdale High School in 1968. Hutchinson attended Bob Jones University in Greenville, South Carolina, graduating with a BS in accounting in 1972. He went on to receive a JD in 1975 from the University of Arkansas School of Law in Fayetteville (Washington County). While at Bob Jones University, he met his future wife, Susan Burrell. They were married in 1973 and have four children.

Hutchinson first held public office as the city attorney of Bentonville from 1977 to 1978. In 1982, Ronald Reagan appointed Hutchinson as district attorney (DA). As the U.S. attorney for the Western District of Arkansas, Hutchinson successfully investigated and prosecuted a group of right-wing extremists called the Covenant, the Sword and the Arm of the Lord (CSA) in 1984 and 1985. Hutchinson also prosecuted Bill Clinton’s younger brother, Roger, on charges of cocaine possession. After his service as the DA from 1982 to 1985, he made the first of several unsuccessful bids for public office by attempting to unseat the popular Senator Dale Bumpers in 1986.

Hutchinson was a partner in the Karr & Hutchinson law firm from 1986 to 1996 and was active in the Arkansas Republican Party. After an unsuccessful attempt to beat Winston Bryant in a campaign for attorney general in 1990, he became the co-chairman and later chairman of the Arkansas Republican Party from 1990 to 1995.

Hutchinson’s older brother Tim was also active in state and national politics, holding seats in the state House of Representatives and as the Third District congressman from 1993 to 1997. After two terms in Congress, Tim Hutchinson decided to run for U.S. Senate, thus leaving the Third District congressional seat vacant. Asa Hutchinson ran and won with fifty-six percent of the vote in a tough race against Democrat Ann Henry in November 1996. He was easily reelected in 1998 and 2000.

Hutchinson was quick to get involved in tough national issues such as drug abuse, bounty hunter reform, and campaign finance reform. He was soon appointed to the Bipartisan Freshman Task Force on Campaign Finance Reform and co-sponsored (with seventy-seven others) the base bill for campaign finance debate in the 105th Congress, the Bipartisan Campaign Integrity Act of 1997 (HR 2183). This piece of legislation sought to limit soft-money campaign contributions and other financial conflicts of interest on Capitol Hill. However, it was bombarded with amendments and did not become law, although it passed in the House.

As a member of the Judiciary Committee and, later, the Committee on Government Reform, Hutchinson was a key player in the investigations that led to the impeachment of President Bill Clinton and was appointed one of the thirteen House managers of the Senate impeachment trial of Clinton on December 19, 1998. Hutchinson was a prosecutor during the Senate impeachment trial and worked closely with the other House managers as they prepared to interview witnesses and present arguments on the Senate floor. As House manager, Hutchinson achieved national and international acclaim and reinforced his reputation for being a level-headed and effective trial lawyer.

As a member of the Veterans’ Affairs Committee, Hutchinson worked to improve veteran healthcare, specifically through the expansion of the Veterans Administration clinic system in northwest Arkansas. For area active and National Guard military personnel, he worked to ensure that the Fort Chaffee base closure would be turned toward the most positive economic and social outcomes possible through working closely with the Fort Chaffee Community Trust. As a member of the Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, he worked to fund major road improvements.

Through earlier experiences as a trial lawyer and district attorney in Arkansas, Hutchinson had developed a special interest in the effects of drug use on individuals and communities. He was nominated for the Speaker’s Task Force on Drugs on June 21, 1999. This task force was in charge of developing a legislative package dedicated to reducing foreign production, drug smuggling, and domestic drug usage. Hutchinson was integral in shining a national spotlight on the particular dangers of methamphetamines.

President George W. Bush nominated him for an appointment in the DEA in June 2001. Hutchinson accepted the job and resigned from Congress on August 6, 2001. He left the DEA to become the Under Secretary for Border and Transportation Security at the Department of Homeland Security in 2003, a position he held until he resigned in 2005.

In early 2005, Hutchinson founded a consulting firm, Hutchinson Group, LLC, in Little Rock (Pulaski County) and also accepted a one-year position with the Venable Law Firm in Washington DC. He drew criticism for negotiating his contract with Venable (the firm has many national and international legal specialties, including national security) while still working as Homeland Security Under Secretary, though he insisted that he complied with the law, working with the legal and ethics team of the Department of Homeland Security.

Hutchinson left Venable in March 2006 to focus on his campaign for Arkansas governor. On June 7, 2006, the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette revealed that Hutchinson had received a $1,080,000 windfall on an investment of $2,800 in Fortress America Acquisition Corp., a shell company that, at the time of his investment, had no revenues, products, or employees; Hutchinson initially failed to report his ownership of this stock on campaign finance disclosure forms. Following a difficult race in which the national shift in public opinion about Republican leadership in the White House and in Congress played a role, Hutchinson lost to Democrat Mike Beebe. Hutchinson re-joined the Venable Law Firm in January 2007. He split his time between Venable in Washington DC and the Hutchinson Group, LLC, in Little Rock before founding the Asa Hutchinson Law Group, PLC, in Rogers (Benton County) in 2008. Following the 2012 massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut, Hutchinson was appointed the head of a National Rifle Association (NRA) task force that, the following year, issued a list of recommendations to combat school shootings, including the training and arming of school staff members. At the time, Hutchinson was also sitting on the board of directors of Pinkerton Government Services, a subsidiary of Securitas, a private security contractor for whom Hutchinson once lobbied while part of Venable and which would have stood to benefit from the expansion of the use of armed security guards in schools.

Hutchinson again ran as a Republican gubernatorial candidate for the 2014 election, defeating former congressman Mike Ross with over fifty-five percent of the vote. His election was part of a larger Republican sweep of the state in which the party claimed all of the constitutional offices and solidified its majority in both houses of the Arkansas General Assembly.

The Republican supermajorities assured passage of Hutchinson’s key agenda items—significant tax cuts, a commitment to computer science education in the state’s schools, and (during the 2017 legislative session) separation of the Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert E. Lee state holidays. Hutchinson was also able to ensure the continuation of Medicaid expansion in the state that was key to balancing the state’s budget and to providing continued health insurance coverage to over 250,000 Arkansans through a combination of support from all Democratic legislators and most of the Republicans. To gain the necessary GOP votes, Hutchinson rebranded the program “Arkansas Works” and, after the election of Donald J. Trump as president in 2016, was able to obtain a waiver from federal officials that allowed a controversial work requirement that bumped thousands of participants from the program.

Over time, some factionalism did show itself among Republican elected officials, with an establishment wing (led by Hutchinson) pitted against a more populist wing grounded in the rural parts of the state with a particular affinity for President Trump. The conflict came to the fore on a number of social issues such as the 2015 battle over the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. Populists favored a more expansive version of the law called the “Conscience Protection Act” that would have allowed individuals and businesses to discriminate against others when state actions led to violations of their religious beliefs. Fearing a nationwide backlash, business leaders in the state raised concerns regarding the act, and, in response, Hutchinson demanded that the legislature revise it in a manner that was consistent with federal law. In the 2018 Republican primaries, establishment Republicans—including Hutchinson—generally fended off populist challengers, allowing the conservative pragmatism of the establishment to remain dominant in the state.

Hutchinson had in 2017 received even more national and international attention (and criticism) because of his attempt to carry out a series of executions unprecedented since the return of the death penalty in the United States in the 1970s. A combination of forces had kept Arkansas from executing any death row inmates for a dozen years. Driven by the coming expiration of one of the three drugs included in Arkansas’s lethal injection regimen, Hutchinson originally scheduled eight executions to be conducted within an eleven-day period in April 2017. Ultimately, four of those executions were blocked by courts, but the other four were carried out despite protests.

During the first Hutchinson term, a multi-faceted corruption scandal surfaced that resulted in convictions and indictments of a number of current and former state legislators and other state officials (including Hutchinson’s nephew, former state senator Jeremy Hutchinson). A thread through much of the scandal was the state’s General Improvement Fund, an allocation of excess state revenues to projects identified for funding by legislators. An Arkansas Supreme Court ruling deeming unconstitutional the process used in the funding as well as the worsening scandal led Hutchinson to advocate the elimination of the program in 2017.

Hutchinson was reelected in 2018 with about sixty-five percent of the vote. In that reelection campaign, Hutchinson focused on his success in implementing the computer science education program and the state’s general economic health. He also promised significant pay increases for teachers and a wide-ranging reorganization of state government if he were allowed a second term.

Hutchinson’s election victory margin was expected, but his success in gaining approval of his major initiatives during the 2019 General Assembly session impressed political observers. Particularly in the terms limits era, second-term Arkansas governors confronted restive legislators with diminished leverage. Hutchinson, however, moved forward with his ongoing program to reduce the income tax while sustaining existing public services through restructuring bureaucracy and collaborating more fully with the private sector.

Governor Dale Bumpers in 1971 had to overcome opposition from entrenched interests to consolidate sixty agencies into thirteen departments, while Governor Mike Huckabee’s efforts in 2003 to pare the executive branch to ten departments floundered in the House of Representatives. During his first term, Hutchinson had established an advisory group to consult with agency directors and prepared legislative leaders for a proposed reorganization that would not expunge current functions nor spark employee layoffs. By the time the legislature convened in 2019, the governor’s plan to meld forty-two agencies into fifteen departments easily passed and took effect within months. While the financial savings from consolidation were modest, the new agency alignments appeared to intensify state government’s mission to bolster job and business development.

The legislature briskly approved a new round of tax reductions that chopped the top rates. Hutchinson and Republican leaders emphasized the fact that lower-income Arkansans had benefited from previous cuts that mitigated the effect of the state’s high sales taxes. Lawmakers were confident that relief for high earners and companies would attract capital and wealthy migrants. The governor took no position on a bipartisan bill that would have aided low wage earners through an earned income tax credit, and the measure died in the House after securing a narrow Senate majority.

Hutchinson and General Assembly majorities boosted revenue for highways and budgeted raises for public school teachers, the same aims pursued by their predecessors. The popularity of better roads and education endured regardless of which party dominated state government. End-of-the-session assessments generally overlooked a significant overhaul of the juvenile justice system. Republican women legislators developed the measure that included, among other reforms, procedures to shift accused juvenile offenders from incarceration in prison-like lockups to appropriate treatment in community programs.

Hutchinson continued to be wary of social and cultural issues that complicated the attraction of industries from other states and nations. He had throughout his career been a staunch anti-abortion advocate and signed nine bills in 2019 that were designed to fortify barriers to abortions. The governor would later express regret, however, over the absence of exceptions for incest and rape in the so-called trigger bill that took effect within hours of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision in 2022 that permitted states to end access to abortion procedures.

While rural conservative legislators had been able to push through contentious measures that fit uneasily in the Hutchinson program, the governor had good reason to believe he could sustain his overall initiatives, harvesting votes at times from the diminished Democratic caucus to compensate for Republican defections.

The confirmation that COVID-19 had reached Arkansas in March 2020 wrenched state government into uncharted territory. The pandemic and the responses to its spread revealed a sharp divide across the nation and in Arkansas stoked opposition to the governor from within his own party. Yet, the massive flow of federal monies into the state over the course of nearly two years allowed Hutchinson to advance his economic program.

Initially, Arkansas was jolted by the recession that battered the national economy and depleted state revenue. After declaring a public health emergency, Hutchinson ordered the shuttering of certain businesses as well as requiring the shift to virtual school instruction. By late April, the governor reversed some business closures as part of a phased lifting of restrictions and discouraged local governments from adopting regulations beyond those he had authorized. Hutchinson’s emphasis upon keeping the economy running and his skepticism over the ability of government to compel personal behavior kept his policies in line with other Republican-led states.

Arkansas was one of the last states to institute a mask mandate (even GOP bastions such as Alabama had done so earlier), and observance was largely voluntary. Local sheriffs and chiefs throughout the state vowed they would not enforce the directive. Nevertheless, Hutchinson’s rhetoric during his daily public briefings did not dismiss the severity of the crisis nor ridicule public health policies, in contrast to the tone that often characterized the pronouncements of President Donald Trump and other prominent national Republicans.

Arkansans who believed that the governor’s restraint endangered health and lives renewed their criticism when Hutchinson announced in August 2020 that school districts had to provide in-class instruction each day of the week. Still, opinion in Arkansas was fractured and passionate. Many residents and elected officials throughout the state raised alarms that the governor’s COVID policies threatened personal autonomy. In February 2021, Hutchinson loosened nearly all of the restrictions, with the exception of the mask mandate, as legislators considered proposals to give the General Assembly a greater role in a public health crisis. The governor terminated the health emergency in May 2021, although COVID variants were beginning to circulate in the state, reinstated the order in August as cases numbers revived, and then allowed it to expire in September. Most states had also lifted emergency declarations by that point.

The onset of COVID vaccine distribution in Arkansas saw a backlash that raged in the country and etched new partisan tensions. During the sessions convening in 2021, Republican lawmakers approved measures prohibiting private employers as well as government agencies from requiring their workers to get vaccinated without offering an exemption process. Hutchinson contended that the General Assembly was risking excessive regulation of private enterprise but could do little as the bills gained veto-proof majorities.

Ideology was not the only mainspring of Republican defiance of the governor, whose public influence was sliding. The Arkansas Poll showed that Hutchinson’s approval ratings had soared during the crisis of 2020 but then sank when the poll was taken late the following year. (Mike Beebe, who was a Democratic governor in a Republican state, had enjoyed notably higher ratings in his last year in office than Hutchinson did in 2021.) This trend tracked Hutchinson’s open criticism of Trump’s sway over the Republican party. The governor’s perspective was an anomaly among Republican officeholders and led to regular invitations to be interviewed on national television news programs.

During this tumultuous period, the General Assembly, which had widened its review of executive agencies’ budgets and operations in recent years, probed for ways to expand its authority at the expense of the governor’s office. The burst of federal COVID-19 relief funds reinforced legislative oversight as departments moved to collect revenue to accomplish long-deferred aims.

Overall, in 2020 and 2021, Arkansas state and local governments gained $8 billion primarily through two major federal laws: the CARES Act, passed in April 2020 with a bipartisan congressional majority, and the American Rescue Plan, relying solely on Democratic votes in March 2021. In addition, federal checks also went to keep afloat Arkansas businesses and individuals during the disruptions of the pandemic and soaring unemployment. The sharp and sudden COVID recession proved to be the shortest in American history, as the federal stimulus that buoyed personal incomes proved a boon for the financial health of state governments.

The guidelines of American Rescue Plan largely allowed the states to decide how to spend the federal money, and on average just under eight percent of the spending in the nation was dedicated to public health purposes and improvement. Arkansas went against the grain, devoting two-thirds of its allotment to the healthcare sector. Much of the balance subsidized a popular objective stretching back to the Beebe administration and designated a priority by Hutchinson: expanding broadband internet service throughout Arkansas to narrow the connectivity gap between rural and urban centers.

In April 2021, shortly before the legislature recessed, Hutchinson explained that careful management had enabled a slight spending reduction for the upcoming fiscal year and that robust tax revenue underwrote the state’s reserve funds. The divisions and emotions stirred during the first pandemic year, however, had led to a combustible 2021 session. Twenty anti-abortion measures, a record number, demonstrated the salience of cultural issues for the Republican majority, while measures intended to check enforcement of federal laws in the state echoed earlier eras of defiance. The legislature also continued to curtail the prerogatives of the constitutionally weak executive. With only majority votes needed to override vetoes, Hutchinson resigned himself to permitting seven measures to become law without his signature while seeing two of his three vetoes upheld.

National coverage and debate surged after the legislature set aside Hutchinson’s veto of a bill banning gender-affirming healthcare for transgender children. Arkansas was the first state to block treatments endorsed by national medical professional organizations for transgender minors and was the first to defend its law in federal court. Hutchinson had signed other acts imposing restrictions upon transgender citizens but viewed the 2021 measure as harmful because it included children already undergoing therapy.

Consistently in the face of criticism from rural conservatives, the governor repeated his long adherence to conservative principles and pointed to the ways he undercut the policies of President Joe Biden. In June 2021, the governor cut off supplemental unemployment payments to Arkansans two months earlier than authorized and in 2022 made Arkansas one of two states to reject additional federal rental assistance.

Above all, continuing tax cuts, including accelerating the drop of the maximum rate to 4.9 percent, defined Hutchinson’s legacy as much as the rise to 7.1 percent and expansion of public services had been the hallmarks of the Bumpers administration. And, yet, lawmakers to the political right of the governor contended that the struggle remained unfinished until the abolishment of the income tax, the source for half of the state’s revenue.

Hutchinson asserted throughout his tenure that a program to limit regulations, assist private business, nurture technological innovation, and create a modern workforce proficient in marketable skills was the proper course for his party in the state and nation.

In April 2022, as he prepared for a trip to New Hampshire, Hutchinson said he was undecided about running for president of the United States in the 2024 election but was not ruling it out. Hutchinson stated on April 2, 2023, that he was running for president, and he said that Donald Trump should drop out of the race following his indictment by a New York grand jury on March 31, 2023. He formally announced his presidential campaign in Bentonville on April 26, 2023. Although he qualified for the first Republican Party presidential primary debate, he did not attract sufficient support to qualify for the second, and he ended his campaign after garnering 0.2 percent of the vote in the January 15, 2024, Iowa Republican caucus.

In August 2024, the University of Arkansas School of Law announced that Hutchinson would be joining the faculty with the spring 2025 semester.

For additional information:

“Asa Hutchinson (1950–).” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=H001014 (accessed April 25, 2022).

Asa Hutchinson Papers (Unprocessed). Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Barth, Jay. “Arkansas’s GOP Factions.” Arkansas Times, May 18, 2017. https://www.arktimes.com/arkansas/arkansass-gop-factions/Content?oid=6824178 (accessed September 7, 2023).

Berman, Mark. “With Lethal Injection Drugs Expiring, Arkansas Plans Unprecedented Seven Executions in 11 Days.” Washington Post, April 7, 2017.

Birnbaum, Ben. “The Totally Not Boring Story of the Most Normal Republican Presidential Candidate.” Politico, August 11, 2023. https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2023/08/11/asa-hutchinson-post-trump-republican-candidate-00110698 (accessed August 14, 2023).

Brock, Roby. “Governor Outlines Legislative Accomplishments, Disappointments.” Talk Business, April 18, 2021. https://talkbusiness.net/2021/04/governor-outlines-legislative-accomplishments-disappointments/ (accessed October 28, 2022).

Cournoyer, Caroline. “Arkansas’ Ambitious Plan to Reorganize State Government.” Governing, October 17, 2018. https://www.governing.com/archive/gov-arkansas-governor-huthinson-reorganization.html (accessed October 28, 2022).

DeMillo, Andrew. “Arkansas Session Marked by Culture Wars, Coronavirus Fights.” AP News, May 1, 2021. https://apnews.com/article/arkansas-cultures-health-coronavirus-business-7617e970d54631663b2572c9283f156e (accessed October 28, 2022).

Greenblatt, Alan. “Patience and Pragmatism Dominate Asa Hutchinson’s First 100 Days.” Governing (April 2015). http://www.governing.com/topics/politics/gov-asa-hutchinson-arkansas-first-100-days.html (accessed April 25, 2022).

Hardy, Benjamin. “Asa at Last.” Arkansas Times, January 15, 2015, pp. 14–18. Online at http://www.arktimes.com/arkansas/arkansan-of-the-year-asa-hutchinson/Content?oid=3618228 (accessed September 7, 2023).

Johnson, Ben F., III. Arkansas in Modern America since 1930. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2019.

Minton, Mark. “Hopeful’s Outlay of $2,800 Pays Off.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, June 7, 2006, pp. 1A, 3A.

Moss, Teresa. “Hutchinson Weighing Presidential Run.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, April 25, 2022, pp. 1A, 4A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/apr/25/hutchinson-hasnt-ruled-out-2024-presidential-bid/ (accessed April 25, 2022).

Murphy, Tim. “NRA Private Security Advocate Works for Private Security Company.” Mother Jones, January 8, 2013. https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2013/01/asa-hutchinson-nra-pinkerton-securitas-lobbyist/ (accessed October 28, 2022).

Thomas, Alex. “With Speech, Hutchinson Makes His ’24 Run Official.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, April 27, 2023, pp. 1A, 6A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/apr/27/hutchinson-a-consistent-conservative-officially/ (accessed April 27, 2023).

Thompson, Doug. “Hutchinson’s New Story an Old One.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, April 23, 2023, pp. 1A, 9A. Online at https://www.nwaonline.com/news/2023/apr/23/presidential-hopeful-hutchinson-has-a-history-of/ (accessed April 24, 2023).

Trimble, Mike. “The Right-Hand Man.” Arkansas Times, April 1986, pp. 40–43, 76–80.

Wickline, Michael R. “Hutchinson Looks Ahead.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 11, 2022, pp. 1A, 8A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/dec/11/hutchinson-looks-ahead/ (accessed December 12, 2022).

Felicia Thomas

University of Arkansas Libraries

Jay Barth

Hendrix College

Ben F. Johnson III

Southern Arkansas University

One of the Hutchinson Family Singers was named Asa. I wonder if Asa Hutchinson, former governor of Arkansas, is a descendant of that Hutchinson family.