calsfoundation@cals.org

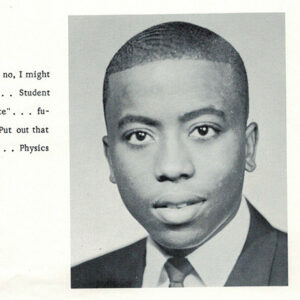

Herbert Denton Jr. (1943–1989)

Herbert Denton Jr. was a leading African-American journalist at the Washington Post. Raised in Little Rock (Pulaski County), the son of a prominent public educator, Denton became the first person of color to hold a supervisory position at the Post. During his career, Denton reported for the metro, national, and foreign desks; served as both Maryland and District editor; hired and mentored a generation of minority journalists (especially African Americans and women); and built a potent legacy of journalistic excellence at the Washington Post.

Herbert H. Denton Jr. was born on July 10, 1943, in Muncie, Indiana, the first of four children of Herbert Denton Sr. and Lucille Battle Denton. “Herbert Junior” spent part of his infancy in Arkadelphia (Clark County), his mother’s hometown, and was living in Little Rock, at 1859 Ringo Street, by the age of two. Later, the Denton family moved to 2107 Pulaski Street. Denton attended Gibbs Elementary and Dunbar Junior High. He was raised in the church at Mount Pleasant Missionary Baptist, where his father was a deacon and later a trustee.

When the Central High desegregation crisis began in 1957, Denton was in the ninth grade at Dunbar, just one grade below the youngest members of the Little Rock Nine. He knew many members of the Nine personally; Ernest Green lived two blocks away from him. During the Lost Year of 1958–59, Denton attended high school in Hot Springs (Garland County). There, a teacher recommended him for a summer program at Howard University in Washington DC.

At the summer program, Denton met another black student who was enrolled at the Windsor Mountain School—a preparatory boarding school in the Berkshires of Massachusetts—and he sold Denton on its quality of education. Denton was able to gain admission with a full scholarship and then convinced his parents to allow him not only to leave Arkansas, but also to forego public education for private.

Denton graduated as valedictorian of the Windsor Mountain class of 1961 and was admitted to Harvard University. He majored in American history and spent a good deal of his time working at the Harvard Crimson. His first article was an opinion piece that defended his refusal to join the nascent Association of African and Afro-American Students at Harvard. This garnered him some notoriety on campus.

Denton graduated from Harvard in 1965 and went to work for J. P. Morgan in New York City, but he quickly changed paths. For about one-fifth of what he was making as a banker, Denton moved to Washington and began co-editing a magazine called The American Student with his best friend from Harvard, Hendrik Hertzberg.

Denton began his career at the Washington Post as a summer intern in 1966. He was drafted into the military that August. After basic training and an assignment in Massachusetts, Denton spent one year as a public information specialist in Vietnam with the First Cavalry Division of the U.S. Army. In the process, Denton earned a Bronze Star for Valor. After two years of service, he left the army at the rank of Specialist Five.

Denton returned to Washington and the Post in August 1968 and began covering education issues, especially those that affected African-American students. He then reported on local affairs in the Maryland suburbs, most notably the controversies of desegregation and busing in Prince George’s County throughout 1972. In 1974, he was named Maryland editor. This marked the first time in the newspaper’s history that a non-white journalist was given command of a section of the newsroom.

In 1976, Denton was named the paper’s city editor. Again, he was the first person of color to occupy this position—a historic achievement made all the more significant by the fact that more than seventy percent of the residents in the District of Columbia were African American, and that Congress had granted the city Home Rule barely two years earlier. As city editor, Denton oversaw coverage of all politics and culture in DC, most notably the 1978 mayoral election that gave Marion Barry the first of his four terms in that office.

In 1980, Denton returned to reporting, this time for the Post’s prestigious national staff. He covered the early years of the Reagan White House, as well as major stories across the United States, including the Liberty City (Miami) riots and the eruption of Mount St. Helens. He also published occasional analysis and opinion pieces, for both the Post and other publications, including a major reflection on the twenty-fifth anniversary of Central’s desegregation in the Post’s Sunday Outlook section.

In October 1982, Denton transitioned to the foreign desk. He was dispatched to Beirut, where he covered the Lebanese civil war. He served as Beirut bureau chief and correspondent throughout 1983 and most of 1984.

In the latter half of 1984, Denton fell gravely ill and was evacuated from Beirut. From November until the end of January 1985, he covered the blockbuster libel lawsuit brought against Time Inc. by Israeli Defense Minister Ariel Sharon in the Southern District of New York. In March, he returned to the Middle East to cover the Iran-Iraq War. This assignment only lasted a month, however, as Denton appears to have fallen ill again.

In June 1985, Denton took what would become his final assignment: bureau chief (and sole correspondent) for the Washington Post in Canada, a position that had not existed until then. For almost four years, Denton was based in Toronto and covered all aspects of Canadian politics and culture, from coast to coast. “Canada is my beat,” he liked to say. His deep and multifaceted coverage of the country earned him tremendous admiration from his journalistic peers in Canada.

Herbert Denton Jr. filed his last story, from Toronto, on April 11, 1989. Several days later, he was rushed to the hospital, where friends would learn that he was suffering from a lethal case of pneumonia, abetted by full-blown AIDS. A host of friends and family members from Washington and Little Rock came to see him in these final days. The vast majority of them never knew that he was gay. Those who did were only able to guess so; he never revealed his sexuality except to a few friends in Canada. On the morning of April 29, by his own volition, Denton was taken off the respirator and slipped into death. A week later, he was buried at Little Rock National Cemetery.

Denton left behind rich legacy at the Post. He profoundly diversified the newsroom through his mentorship of Juan Williams, Courtland Milloy, Milton Coleman, Gary Lee, Keith Richburg, Athelia Knight, Cynthia Gorney, Dorothy Gilliam, and many other reporters. Leonard Downie Jr., who succeeded Ben Bradlee as the paper’s executive editor from 1991 to 2008, counts Denton as one of his greatest mentors at the Post, despite having been Denton’s superior in the management hierarchy during the time they worked together.

For additional information:

Coleman, Milton. “The Life and Times of Herbert Denton.” https://erinroberts.atavist.com/herbdenton (accessed February 4, 2020).

Denton, Herbert H., Jr. “Afro-Americans.” Harvard Crimson, May 14, 1963. Online at https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1963/5/14/afro-americans-psome-time-ago/ (accessed February 4, 2020).

———. “The Deeper Dilemmas of Little Rock.” Washington Post, September 5, 1982. Online at https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/1982/09/05/the-deeper-dilemmas-of-little-rock/5243291a-4089-4db2-a9be-16c5f478b8b5/ (accessed February 4, 2020).

“Herbert Denton Jr., Post Reporter and Editor, Dies.” Washington Post, May 1, 1989. Online at https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1989/05/01/herbert-denton-jr-post-reporter-and-editor-dies/fea9bd6a-bc9d-4ed8-8224-9d249a923401/ (accessed February 4, 2020).

“Herbert Denton, 45, Foreign Correspondent.” New York Times, May 2, 1989, p. 6B.

Benji de la Piedra

Central Arkansas Library System

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Mass Media

Mass Media Herbert Denton Jr.

Herbert Denton Jr.  Herbert Denton Jr.

Herbert Denton Jr.  Herbert Denton Jr.

Herbert Denton Jr.

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.