calsfoundation@cals.org

Higher Education

Formal education above the high school level came to be known as higher education in the twentieth century. In Arkansas, higher education appeared, at least in name, prior to the Civil War, but the state university and most of the private institutions were postwar products.

Early Nineteenth Century

During Arkansas’s colonial period (1686–1802), there is no evidence of any public interest in higher education and little interest in even the most elementary sort. The transfer of Louisiana from France to the United States resulted in the arrival in Arkansas of numerous persons with backgrounds in higher education. James Miller, the first territorial governor, had attended Williams College in Massachusetts, as had Chester Ashley, the leader of the state bar association and also a graduate of the Litchfield Law School in Connecticut. The first territorial delegate, James Woodson Bates, had attended Yale and graduated from Princeton. The most educated early official was the second territorial governor, George Izard, whose education career began in France at the College of Navarre and included attendance at Columbia University in New York City and the College of Philadelphia.

On March 2, 1827, Congress set aside from public sale two townships per state or territory (seventy-two square miles, or more than 46,000 acres) “for the use and support of a university…and for no other use or purpose whatsoever.” Originally, the grant was in the hands of the governor, but in response to pleas from legislators, Congress turned control over to them and in subsequent legislation removed the restrictions on how the land was to be treated. In what has been called “The Swindle of the Century,” not only the land itself but also the proceeds from what was sold disappeared, never even to be properly accounted for.

As soon as Arkansas became a state, Whig legislator Anthony H. Davies, a banker and planter from Chicot County, called for creating a “University of Arkansas.” Opponents ridiculed the idea of education and proceeded to pass a tax cut instead. Thereafter, governors occasionally harped about higher education, but perhaps typical was the observation of John Selden Roane who wondered where college students would come from when Arkansas still lacked common schools.

While seminary fund monies disappeared in the legislature, private initiative tried to step in. The most ambitious project was the Far West Seminary, to be located outside of Fayetteville (Washington County). Missionary and educator Cephas Washburn was the guiding light. Although the legislature passed a charter for the intended school, Democrats in the region voted against it, and religious and even educational prejudices were manifest. Unfortunately, the depression of 1838 had reached Arkansas, leading to a shortage of funds. Just prior to the school’s planned opening, a fire destroyed the only building, and the project had to be abandoned.

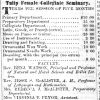

In the late 1840s, Arkansas’s Catholic bishop, Andrew Byrne, attempted to found an Irish colony and St. Andrew’s College in Fort Smith (Sebastian County), but the effort failed. Other antebellum failures, mostly from Presbyterians and Methodists, included Arkansas Synodical College and the Arkadelphia Female College in Arkadelphia (Clark County), the Jefferson Female College at Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), the Mine Creek Male and Female College in Hempstead County, the Ouachita Conference Colleges at Camden (Ouachita County) and Tulip (Dallas County), and Makemie College and Soulesbury Institute in Batesville (Independence County). Phi Kappa Sigma College, apparently the first and only institution to be named for a fraternity, opened in Monticello (Drew County) in 1859. It boasted the Philomathean Literary Society but closed at the outbreak of the Civil War.

In the 1850s, when prosperity reappeared, Fayetteville was again the educational center of the state. Nearby Cane Hill College was supported by the Cumberland Presbyterians. A neighboring female seminary offered similar opportunities. Cane Hill College granted the first bachelor’s degree in 1856. The Reverend Fontaine Richard Earle became president in 1859 and revived the institution after the Civil War. It then admitted women students, granting degrees to them in 1877.

Another Washington County project was Robert Graham’s Arkansas College (the first of two schools bearing that name, the other being a postwar creation in Batesville). An English-born carpenter, Graham had helped build Alexander and Thomas Campbell’s Bethany College (now located in West Virginia), stayed to get a degree, and then came to Arkansas, moving to Fayetteville in 1848. Graham was anti-slavery and left the college (and the state) prior to the Civil War. His successor, William Baxter, witnessed the burning of the college during the war.

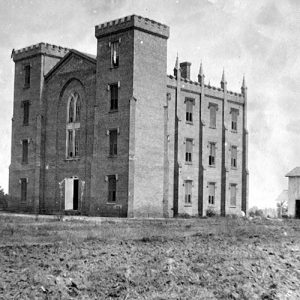

One major pre-war attempt epitomized the internal divisiveness characteristic of the state. Albert Pike used his power as a Mason to organize a planned Masonic-supported institution in Little Rock (Pulaski County). Named St. Johns’ College, it was chartered in 1850, but no work on the campus started until 1857, and the first class finally met in 1859. One major cause of the delay was that Helena (Phillips County) Masons sparred with Little Rock Masons over railroad funding issues and retaliated by encouraging other chapters not to pay their assessments. Repeated postwar attempts to vitalize the institution, first by Republican Ozro A. Hadley and then by Methodist minister Rev. Augustus R. Winfield, failed.

Creation of the University of Arkansas

The absence of education-hating Democrats in the U.S. Congress in 1862 made possible the passage of Justin S. Morrill’s prewar bill, which became known as the Morrill Act. The law made extensive federal land grants to the states based on the number of senators and representatives. Arkansas was entitled to 150,000 acres of public land specifically to support “at least one college.” Institutions were required to offer “military tactics” as well as “liberal and practical education.” Arkansas’s Union government under Isaac Murphy accepted the terms in 1864 and again in 1867. The Constitution of 1868 mandated establishing a state university, and the Republican legislature elected under that constitution passed “An Act Creating an Industrial University” that same year. In 1871, a second enactment called for the state’s towns to bid for the university, which was snagged by Fayetteville. Since Arkansas still had not paid the U.S. government the monies due on state bonds, there was resistance in Washington DC to giving any more aid to the defaulting state, but ultimately the issue was resolved in Arkansas’s favor.

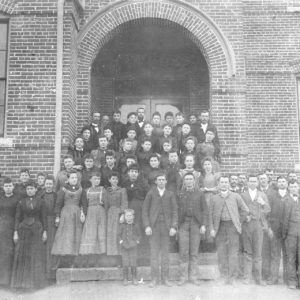

Arkansas Industrial University, now the University of Arkansas (UA), opened its doors on January 22, 1872, as eight students registered in the preparatory program. Of necessity, the university operated mostly as a high school, as such were lacking in Arkansas, until the twentieth century. Indeed the first “graduation” in 1872, consisted of preparatory students.

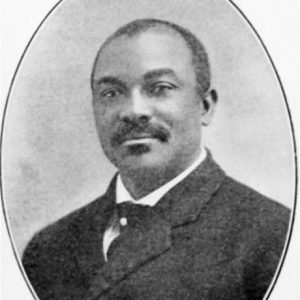

The state’s public schools were segregated by race, but two black students were admitted. Both were taught separately by the president, and neither graduated. The Republicans never got around to creating a college for African Americans, but in the aftermath of the Brooks-Baxter War that ended Reconstruction, Democrats promised to act on that. Thus, in 1875, Branch Normal College, designed to train black teachers, opened in Pine Bluff with Joseph C. Corbin as “principal.” Corbin, a graduate of Ohio University, remained at the school until ousted by Governor Jeff Davis in 1901. Branch Normal later became Arkansas AM&N College and then the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff (UAPB).

Late Nineteenth-Century Developments

With the collapse of public education after 1875, academies sprang up around the state. Although often the work of individuals, they sought a church connection in hopes of securing more students, and they included words suggestive of college in their titles. The list of these failed institutions is extensive. Northern Methodists between 1882 and 1896 failed to make a go of the University of Little Rock. Southern Methodists fared no better with the Arkansas Female College between 1874 and 1883, despite its location in Albert Pike’s commodious former home. Education historian Robert W. Meriwether believed that Quitman Male and Female College probably taught the first “real college courses.” Typical of the failed institutions of the period was Buckner College located at Witcherville (Sebastian County). Founded by prominent Baptist minister Ebenezer Lee Compere in 1875, the school endured until 1904 but changed denominational hands at least four times. The grandiloquently named Judson University was actually a Baptist academy with only five teachers.

As the century moved to a close, public schools slowly arose from the ruins. This left the academies with two choices: close or become colleges. The Methodist academy in Imboden (Lawrence County), Sloan-Hendrix, became that town’s public school building. A different route was taken by Central Institute. Founded at Altus (Franklin County) by Rev. Isham L. Burrow in 1876, it became Central Collegiate Institute in 1881 by adding college preparatory instruction. In 1889, the primary department was discontinued, and in 1890, after asking for bids, the school moved to Conway (Faulkner County), becoming Hendrix College. This “official” Methodist men’s school admitted women, although in 1899 Methodists established Galloway College in Searcy (White County), which once reportedly sported the largest female enrollment in the South.

Regionalism was strong even in the centralized Methodists. Conway’s securing of Hendrix College spawned a bid to create a south Arkansas rival. Hence, in 1890, Arkadelphia Methodist College came into being. In 1904, it was renamed Henderson College, and then in 1911, it became Henderson-Brown College.

Higher education also took place among Arkansas Catholics. A mission priory called New Subiaco Abbey was established in Logan County in 1878. St. Benedict’s College was created in 1887. The first college classes consisted almost entirely of children from German Catholic families so that English was taught as a foreign language. After reorganization, it became Subiaco College and Academy.

Nearly parallel was the early history of Ouachita Baptist College (now Ouachita Baptist University). It grew out of Ouachita Baptist High School in Arkadelphia (Clark County), located on the former grounds of the Arkansas School for the Blind. The state Baptist convention had become convinced of the need for a college, and Arkadelphia bid it in. The school opened in 1886. John William Conger rooted the school in classical education with a co-educational setting. Central College in Conway was the Baptist response to educating females. This institution failed in 1947, but the campus was then acquired by the Baptist Missionary Association of Arkansas, a more conservative group, and reborn as Central Baptist College.

Presbyterians in Batesville (Independence County) responded to their losing bid for Arkansas Industrial University by snagging Arkansas College (known as Lyon College after 1994). Rev. Isaac J. Long was both the creator and first president, and this institution shed its primary department in the 1890s and its secondary department in the 1920s. One third of its early graduates were headed for the ministry. Cumberland Presbyterians had more problems. Their flagship institution, Cane Hill College, declined in the face of competition from Arkansas Industrial University, the passing of school leader Rev. Fontaine Earle, a disastrous fire, and no railroad connections. The state synod then shifted its support to Arkansas Cumberland College in Clarksville (Johnson County). Denominational changes led the school to become the College of the Ozarks in 1920 (and the University of the Ozarks in 1987).

Parallel developments took place among the separate and substantially unequal African-American colleges. Pine Bluff’s Branch Normal remained largely a high school well into the twentieth century, although still a nominal branch of the state university. Nevertheless, it bestowed ten bachelor’s degrees between 1882 and 1894. In 1890, Congress passed another Morrill Act, requiring Southern states either to show that their land grant universities had non-discrimination policies or that they had created separate but equal educational facilities for African Americans. This had the effect of creating what later would be styled public historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs), and it made Branch Normal a self-standing land-grant college, albeit one that, in 1894, was reduced to a junior college and which remained in this obviously unequal status until 1929. Pathetically under funded, it ranked at the bottom among similar Southern schools and was not even accredited until 1950.

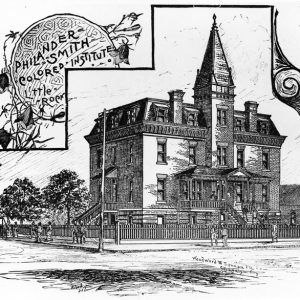

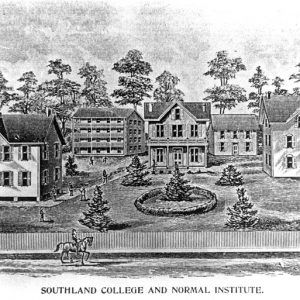

Black religious denominations paralleled white ones in college creation. The oldest institution was Southland College. Begun in 1864 as an orphanage in Helena (Phillips County) for displaced black children, it was supported by the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) and endured until 1925. Bethel University turned into Shorter College in North Little Rock (Pulaski County), sponsored by the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. Across the river, Philander Smith College began as Walden Seminary in 1877. It was sponsored at first by Northern Methodists and eventually by the United Methodist Church. Arkansas Baptist College, founded in 1884 as Minister’s Institute, became the state four-year liberal arts college for Arkansas’s National Baptists.

Nineteenth-century student life differed markedly from that in the twentieth century. Most of the early colleges did not have dormitories, with the result that out-of-town students boarded out and locals lived at home. Rules were strict. General Daniel Harvey Hill at Arkansas Industrial University was more likely to expel students for acquiring too many demerits than for getting bad grades. But probably the most contested disciplinary issue concerned persons of the opposite sex. Parents hoping to secure the safest environment for their daughters often sent them to women’s schools, but no state institution for women came into being in Arkansas. Hendrix College, which admitted women, had, under President Alexander Copeland Millar, this rule: “No student is allowed to communicate orally, by writing, or by sign with students of the other sex.” Daily (and later weekly) chapel and Sunday school attendance were required. Until the 1890s, most student organizations were academically based. Students at postwar St. Johns’ College had a student newspaper, and various debating clubs and literary organizations abounded.

Early Twentieth-Century Developments

The 1890s saw the introduction of college football. Soon virtually every college in the state had teams, and college life became centered on sports rather than academics. In place of former literary societies, fraternities and sororities arose. “Rush” became central to the college experience, and liquor, dancing, cigarettes, and gambling, among other vices, crept into college life. Hendrix College embodied these changes more than any other institution in the state. In 1923, the school erected Young Memorial Stadium, a 5,000-seat football arena; around that time, their historic literary magazine, the Mirror, shut down for lack of support, and their two literary societies, once the center of college life, became defunct. In the 1920s, Methodists engaged in an internal debate over the value of sports, and Hendrix de-emphasized its program.

There were some signs that intellectual concerns did matter. At Fayetteville in 1912, thirty-six students put out an underground newspaper called X-Ray that criticized a number of university and local conditions. All thirty-six, including most of the leading students on campus, were expelled. A majority of the rest of the student body (724 in number) protested, boycotted classes, and paraded through Fayetteville’s downtown. Another crisis in 1919 led to five expulsions and a number of suspensions. One result of the crisis was the creation of student government on the Fayetteville campus.

While working-class students were not unknown, higher-education students typically came from the middle classes and either returned to their communities to assume eventual control of family businesses or headed off into the greater world. Typically, their children attended the same institutions.

Despite the relative weakness of all education in Arkansas, the office of state superintendent of education was vigorously contended for in Democratic Party conventions, and college presidents such as John Hugh Reynolds and Alexander Copeland Millar could be found in many other state endeavors. The climax came in 1917 when former UA professor Charles Hillman Brough became governor of Arkansas. Never before or after were educational leaders as important in state life.

The evolution of Arkansas institutions of higher education was slowed by the state’s poor showing in elementary and secondary education. In 1917–1918, Arkansas ranked next to last, with only 6.9 percent of the age-eligible children enrolled in high school. Further, the total number of high school graduates that year was a mere 979.

Training teachers had been a concern for half a century when Superintendent of Public Instruction Josiah H. Shinn decided to provide state support for Arkansas Normal College, a private school in Jonesboro (Craighead County). Unfortunately, the depression of 1893 and a fire ended this experiment. Arkansas entered the new century still with its only state-funded normal (i.e., teacher training) school being for African Americans at Pine Bluff.

The first important development in the new century was the creation of a teachers’ college at Conway in 1908. First called Arkansas State Normal School, it became Arkansas State Teachers College in 1925 and is now the University of Central Arkansas (UCA). By that time, though, all colleges were turning out teachers. Meanwhile at Pine Bluff, not only was long-time principal James C. Corbin fired but Governor Jeff Davis, who elevated bigotry into his credo, consistently vetoed the institution’s already pitiful state allotments.

The idea that Arkansas needed educated white farmers found a ready response from the Farmers’ Union. Their push for agricultural high schools succeeded—with four being established in Jonesboro, Russellville (Pope County), Monticello (Drew County), and Magnolia (Columbia County)—but then was trumped when the federal government began giving aid to all high school agriculture programs. The four schools did not disappear but instead, by four different routes, began their twisted processes of becoming universities. Little Rock, which did not get an agricultural high school, spent the early 1920s trying to get UA moved to Little Rock. Allied in this were groups that wanted engineering and agriculture sent to Russellville. The Arkansas University Removal Association, unable to win in the legislature, also abandoned trying to get the issue on the ballot in 1924.

A third development was the first appearance of junior colleges. The argument that the first two years of basic education courses could be farmed out reached Arkansas in the early twentieth century. Crescent College, housed in the historic Crescent Hotel in Eureka Springs (Carroll County), operated as a women’s school from 1908 to 1934. In 1927, longtime legislator William H. Abington crafted a bill for a junior agricultural school, the legislative requirements of which meant that only Beebe (White County) could house the institution. In 1931, the school became the first state-operated junior college. A third junior college was operated by the El Dorado (Union County) school board between 1925 and 1942; Fort Smith engaged in a similar operation. Dunbar Junior College started in 1929 in Little Rock’s African-American high school. Finally, Little Rock Junior College, supported with funds from the Donaghey Foundation, opened in 1927. A proposed constitutional amendment in 1942 to allow tax support for junior colleges failed to pass.

A fourth development in the twentieth century was the rise of graduate schools. The oldest was the medical school. Begun as the School of Medicine of Arkansas Industrial University in 1879, it was privately owned and received no university or state assistance. A rival College of Physicians and Surgeons appeared in 1906. The American Medical Association’s Flexner Report in 1909 observed that “neither has a single redeeming feature” and found it “incredible” that the university allowed its name to be used. Major reforms followed with Dr. Morgan Smith becoming dean in 1912.

The School of Law at Fayetteville started as the Little Rock Law Class in 1868, but no official university affiliation followed despite some discussion. Then, in 1890, the university created a school in Fayetteville with Frank M. Goar as dean. The result was so bad that Goar moved to Little Rock in 1893, where he enlisted the services of George B. Rose, Thomas B. Martin, and other well-known practitioners. The law school continued despite Goar’s death in 1898, but while the state assumed responsibility for the medical school, the crisis also prompted the university to disaffiliate itself from the Little Rock operation, which thereafter was called the Arkansas Law School, with John H. Carmichael, one of the state’s premier attorneys, serving as dean until his death in 1950. The University of Arkansas School of Law was finally created in 1924 at Fayetteville with Julian S. Waterman, a president of the Southwest Athletic Conference and prolific writer of legal articles, as dean. What had been the Arkansas Law School is now the University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law.

Arkansas has always lacked dental and veterinary schools. Dental care was not a rural priority; the absence of a numerically important middle class would have left most dentists without any real clientele. Regarding the latter, virtually every farmer was a veterinarian of sorts, but it was also true that the low level of the stock made vet expenses impractical.

Finally, the educational world remained fluid. On the one hand, the Methodists abandoned their Southern outpost, Henderson-Brown (having merged the students into Hendrix College), deeding it to the City of Arkadelphia—which then deeded it to the State of Arkansas—in 1929; it became Henderson State Teachers College (now Henderson State University). On the other hand, the Baptists continued creating more schools than they could support. Jonesboro first had Woodland College in the early years of the twentieth century and then Jonesboro Baptist College. A two-year institution that nevertheless sported a football team appeared at Mountain Home (Baxter County). Catholics created Little Rock College in 1908 in downtown Little Rock. In 1911, the Seminary of St. John the Baptist held its first classes at the college. In 1916, the college and seminary moved to new buildings (now the diocesan headquarters building in Pulaski Heights), but the seminary in 1920 moved back to the old site.

A group of outside experts led by Arthur J. Klein offered the first objective evaluation of state-funded schools. Declaring that Arkansas could afford to create adequate institutions if the will existed, the panel analyzed in detail a multitude of problems. The medical school, for example, was so inadequately housed in the Old State House that it was “a menace to American standards of health” and needed to be closed. At Russellville, where local interests “exercise a sinister influence over the institution,” so many things were wrong that the authors urged closing the college. Everywhere they found inferior dormitories, bad sanitation, and (at Monticello) students sleeping in flooded basements. Although the report made headlines in the Arkansas Gazette, its detailed proposals were ignored. Other even greater problems had surfaced.

Depression and World War II

Arkansas was hard hit by the drought of 1930–1931 and the subsequent collapse of cotton prices. The immediate impact on higher education was that students disappeared as middle-class families saw their incomes disappear. Small, already-struggling religious schools felt the blow the hardest, and Depression-era closings included Subiaco College (although the academy endured), Little Rock College, Mountain Home College, Jonesboro Baptist College, Crescent College, Arkansas Holiness College at Vilonia (Faulkner County), and Galloway College. All schools slashed salaries. One form of student aid common to the period consisted of colleges employing students to work on campus. At Arkansas State College, now Arkansas State University (ASU), the pay was fourteen cents an hour. The New Deal’s National Youth Administration (NYA) aided these programs, with the result that enrollments not only recovered but increased. More federal money came from government loans and from the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and other federal sources, resulting in a number of substantial new buildings.

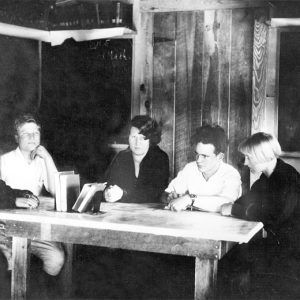

A somewhat different impact came from Polk County, home of Commonwealth College. A labor school that had moved from Louisiana to Arkansas, it sported a cosmopolitan enrollment known locally for mixed swimming and other egregious sins. Commonwealth long had been accused of communist leanings, and during the 1930s, it supported the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union (STFU) by producing pamphlets and attacking the sharecropping system. A subsequent legislative investigation prompted the passage of legislation that finally shut down the school in 1940.

State colleges benefited greatly from federal assistance, and enrollments were up by the late 1930s. Numerous specialized degree programs were begun. Scientific agriculture replaced the “practical” courses that emphasized student labor. Business administration programs came to the fore, as did journalism. The heightening world crisis was reflected in the addition of Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) programs (but not at Pine Bluff’s AM&N) and the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPT).

Congress instituted a prewar draft of eligible young men in 1940. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, higher education faced new challenges. The first, politics, manifested itself most conspicuously at UA. Following the death of long-time president John C. Futrall, Governor Carl E. Bailey, the chairman of the university’s board of trustees, led in selecting law professor J. William Fulbright as the new president despite his young age. At the same time, the board adopted a policy fixing sixty-five as the retirement age. This move was aimed at removing professors who had made political enemies, among them being David Yancey Thomas, the outspoken political scientist. Following Bailey’s failure to win a third term, the new governor, Homer Adkins, packed the university’s board, and in 1941, it fired Fulbright. Public discontent resulted in the passage of constitutional Amendment 33, which prevented future board-stacking and gave staggered terms to board members. Not only was the university covered, but so were all state institutions.

The second problem was a lack of male students as many left for war. Campuses became training schools, with a hangar and flying fields at Arkansas State College. Arkansas State College had grown to about 430 students by 1939 but fell to 114 in 1943. At Fayetteville, graduate offerings almost ceased, but more than 2,400 U.S. Army Air Corps students made up the difference. At Fayetteville, a federally funded research program, Army Ordnance–Arkansas (ORDARK) began classified research under Dr. Wladimir W. Grigorieff. Another program, Arkansas–Naval Ordnance (ARNO), followed.

Private schools did not share equally in war’s largess, and thereafter the balance shifted to public rather than private education. The war did coincide with the creation of another Baptist school, Southern Baptist College, founded by Hubert E. Williams in Pocahontas (Randolph County) in 1941. After the war, it moved into part of the former air force base at Walnut Ridge (Lawrence County) and eventually became Williams Baptist University.

The GI Bill and Baby Boomers

The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly called the GI Bill, gave returning veterans every incentive to attend college. Despite Arkansas’s low high school graduation rate, the effect on college campuses was considerable. First, returning veterans were serious about their studies. Second, many had wives and children, so married student housing became an issue for the first time in Arkansas history. Third, their numbers were simply overwhelming. Arkansas State College in 1946 witnessed an enrollment increase of 300 percent. By 1948, there were 1,093 registered students. Finally, although veteran enrollments tapered off after 1951, Initiated Act Number One of 1948 forced consolidation, thus setting the stage for universal high school education and increasing the pool of future college enrollees.

These dramatic enrollment increases upset the legislative appropriation plan, in place since 1909, which gave equal allotments to each of the state colleges. Arkansas State College in 1949 was able to get a separate appropriation, but the precedent proved to be of little value as hard times in the 1950s strained the already underfunded colleges. A 1951 study marked the first attempt to survey existing conditions. The Arkansas Commission on Higher Education included all the state’s college presidents and chancellors, as well as five state representatives, three state senators, and four gubernatorial appointees. Although in later years, the presidents and chancellors would wage war against the Department of Higher Education, the consensus in 1951 was that a co-coordinating board was a top priority, along with uniform accounting procedures. The commission put the blame on the state for not acting and also gave examples of obsolete laws still on the books. Both teachers’ colleges (Henderson and State) were supposed to require students to teach in Arkansas for two years after graduation. The “art of textile manufacturing,” along with agriculture and horticulture, was mandatory at the former district agricultural high schools. Paid leaves, for example, elsewhere called sabbaticals, were illegal. Like most reports, it was printed, filed, and forgotten.

One carryover from the war years was research at UA. Organized in 1948 and headed by Grigorieff, the Institute of Science and Technology sought to coordinate campus research projects, win funding from outside sources, and assist state agencies and the Arkansas State Chamber of Commerce in economic development. Opposition from within the university and from opportunistic politicians led to the dismantling of the institute in 1955, thus preventing Fayetteville from developing into a research center like North Carolina’s research triangle.

During this period, controversy arose over race issues. Desegregation in Arkansas had a twisted history. In contradistinction to the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada (1938), Arkansas had never established a law school or any other kind of “separate but equal” graduate school programs. Thus, both the medical and law schools desegregated in advance of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (1954). Silas Hunt, the first to integrate the law school, died of tuberculosis shortly after enrolling. Jackie L. Shropshire, who took his place, was supposed to sit in a little cage during class, but it quickly disappeared.

Following the crisis at Central High School in Little Rock, segregationists, who controlled the legislature, passed Act 10 in 1958, requiring every teacher to file a report listing every organization to which he or she had belonged or had contributed to during the past five years. Coupled with the legislative finding that the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was a communist organization, Act 10 set the stage for massive purges. Some instructors refused to return their forms and were fired. After the act was declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in Shelton v. Tucker (1960), the university refused to reinstate one of the fired faculty members at Fayetteville who still wanted to remain in Arkansas. Rebuffed by the president and board, John L. McKenney took his case to the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), with the result that in 1964 UA found itself on the “List of Censured Administrations.”

Meanwhile, Arkansas began losing population as machines were replacing people in agriculture. High school seniors and college graduates shared one feature: they often left the state after graduating at rates that exceeded fifty percent. The “brain drain” reflected the harsh reality that there were indeed few jobs for educated Arkansans. The state in 2014 ranked ahead of only West Virginia in being home to the fewest college graduates.

After some stability in the 1950s, enrollments began to grow again as the first of the wartime baby boomers entered college. Their enrollments were followed in very short order by the postwar baby boomers. Again, classes and dormitory space were at a premium, while the same population spikes resulted in shortages of qualified faculty. Virtually every degree program had to meet certain national standards in order to be certified. As a result, the number of PhDs grew rapidly after the war. Arkansas State College president Carl Reng used these PhDs and the new programs as proof of the school’s claim to university status. Similar developments took place in private schools. Hendrix College, which had only two PhDs in 1923 and had just fired its best-qualified professor for pro-Darwin statements, had a faculty by the 1970s consisting of more than half with terminal degrees.

The coming of PhDs as well as decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court led to a growing secularism. Compulsory chapel in state institutions was abandoned in the 1950s and early 1960s, although official prayers and other constitutionally suspect religious activities often remained. Hendrix College abolished compulsory chapel in 1967. However, the much more conservative Church of Christ institution, Harding University, in 2014 considered chapel central to its mission and required daily chapel for all students registered for nine or more hours. John Brown University held chapel twice a week, and Ouachita Baptist University had attendance at three-fourths of the chapel sessions as a graduation requirement.

Growing pains were felt all over the state but more strongly in northeast Arkansas, where Arkansas State College was attempting to gain university status despite the persistent opposition of UA. Repulsed in 1961, the college’s board used the gubernatorial election of 1966 as its springboard. The Democratic nominee, James D. “Justice Jim” Johnson, printed up bumper stickers reading “Jim Johnson and ASU.” Republican Winthrop Rockefeller would only admit that the college had “ingredients” for attaining university status. The legislation passed in January of 1967, and Arkansas State College became Arkansas State University.

What was seen as a major triumph and a great step forward ultimately had little meaning. Over the next decade, every other state college turned into a “university,” and name inflation reached into the state’s private institutions as well, leaving by 2014 only a handful of schools that did not claim the supposed high status the term implied.

Unleashed in the process was a vicious battle for state funds. Educational values had little to do with legislative largess, which depended on lobbying and influence. Complicating the matter was that enrollments went up and down depending on the state of the economy (bad times made for more students than good times) and the birth rate. Educational expenses for faculty were less flexible, so crisis after crisis became the norm in state-funded higher education.

The first attempt to make order came in 1961 with the creation of the Commission on Co-Ordinating Higher Education Finance (CCHEF). After some attempts to fulfill its mission only to encounter legislative hostility, the head and staff resigned in 1969 and suggested that the commission be abolished. Instead, it was renamed the Department of Higher Education in 1971. While it was able to investigate duplicate programs, attempts at enforcement failed. First, the legislature continued to micromanage to the point, in 1981, of attempting to abolish the department and deny it any funds. As early as 1975, it was unable to stop Southern State College (now Southern Arkansas University) in Magnolia from setting up a junior college in El Dorado.

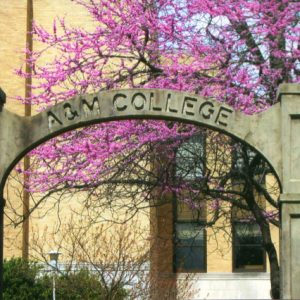

In the late 1960s, rapid changes hit state higher education. The first consisted of the financial collapse of two state institutions, AM&N at Pine Bluff and Arkansas A&M at Monticello (now the University of Arkansas at Monticello). The historically black college AM&N at Pine Bluff desperately needed money, but fiscal investigations did not reflect well on its president. In addition, while black college enrollments had doubled by 1966, the increases were going to formerly all-white schools. Also in danger of closing was A&M at Monticello. Regionally important, especially with its forestry program, it too could not be allowed to shut down. Both schools were then incorporated into the University of Arkansas, which, in the case of Pine Bluff, reestablished the legal relationship that had existed at the beginning. Slightly different was the case of Little Rock University. Its 3,256 students in 1967 made it the fourth-largest institution in Arkansas. Despite talk of merging it with State College of Arkansas at Conway (earlier Arkansas State Normal College and later University of Central Arkansas), it too was added to the emerging UA “system,” becoming the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UALR).

Second, the legislature succumbed to the lure of junior colleges. Every county could have one, so the argument went. The main financial burden was to rest with local communities who would have to authorize a millage to support the schools. Support turned out not to be universal. Baxter County initially rejected having a junior college in 1973, largely because of the fear of higher taxes. Further, in 1978, both Phillips County Community College and Garland County Community College got into trouble by firing teachers without due process. Both were censured by the AAUP, and neither censure has ever been erased, even though the Helena institution was later taken into the UA system. That move was widely seen at the time as a way to keep local African Americans from gaining control of its board. The Hot Springs (Garland County) institution changed its name to National Park Community College but refuses even to acknowledge its censured condition.

Hard times in the 1970s prompted Governor David Pryor to commission another study. The outside consultants in 1978 said Arkansas needed intelligent planning and a department with real powers. Instead, the legislature spent the early years of the decade trying to get Grant Cooper, a UALR professor, fired because of his membership in the Progressive Labor Party. A 1980s study revealed disparities in pay for males and females in the extension service programs. Sex discrimination suits followed on many college campuses.

Governor Frank White in 1981 admitted that the state could not afford eleven “major” universities, the growing number of junior colleges, and the vocational-technical schools. UA board member James Blair replied that such opinions were typical of someone who could not pronounce correctly the words “library” or “incarcerate” and who “thinks Taiwan is in the Middle East and believes religion is science.” Although every state college had become a “university,” funding was often in the “C” category, meaning that no revenue was expected. In some years, even “A” funds, the highest level of expected funding, had to be cut. In 1990, the flush Razorback Foundation, which feasted off the football and basketball programs, gave $350,000 to the UA library.

Arkansas was not out of the woods on integration. In 1983, the Office of Civil Rights found that problems still existed. Racial incidents occurred in private schools, notably the College of the Ozarks (now the University of the Ozarks), but the deepest resentment among the black community was the loss of an independent AM&N.

Civil rights issues also included the emerging student opposition to the Vietnam War. Joe Neal and his wife were officially expelled from Arkadelphia (Clark County) for the “crime” of speaking against the war to students, a move that led to the organization of the state chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). Such “outsiders” aroused the ire of legislators, and UA responded in 1962 by banning all speakers, including even the state’s gubernatorial candidates. As off-campus radical underground newspapers appeared, often with the encouragement of faculty members, some administrators fought back. Carl Reng at ASU by 1972 had a purge list of forty-two faculty members. Grounds for firing included being a member of the AAUP or the Republican Party. Private schools had their difficulties as well. Firings at Philander Smith College resulted in that school receiving AAUP sanctions.

Recent Developments

Despite fiscal problems, state institutions pushed ahead with the special agendas. UCA in 1995 set up doctorate programs without approval of the Department of Higher Education. Amendment 33, the school argued, made its board exempt from state control. UCA also concentrated on getting as many students as possible, figuring that student numbers would lead to eventual funding.

Lacking adequate state assistance, the state schools proceeded to raise tuition. At UA, a single semester in 2015 cost $8,521 in tuition and $3,509 in room and board. Out-of-state students faced tuition charges twice as high. Hendrix College was the leader in costs, with a tuition rate of $40,520 per year in 2015. Such rates seemed astronomical to many Arkansas residents but were relatively modest compared to national norms. Some institutions kept tuition increases down by substituting fees. Automobile parking became another source of income as institutions kept increasing their fees, while campus police forces generated considerable income from traffic tickets. The shifting of the financial burden from the state to the student was funded in part by student loans.

Major changes also took place among faculties. During the late 1960s and 1970s, Arkansas benefited from a surplus of PhDs. These professors were able to staff effectively many of the new or expanded programs. Faced with monetary restraints, universities failed to replace many of these professors as they retired in the 1990s and early twenty-first century. Instead, “adjuncts” became popular. These professors were retained to teach individual classes but were denied health insurance, tenure, retirement, and other normal rights. The “out-sourcing” of faculty had many other parallels that included selling off dormitories, the college bookstore, and food services to private enterprises. In some instances, notably at ASU, the greatest need was to produce somewhere in the vicinity of $1 million to cover the deficit from the athletic department’s expenses.

Faculties were also impacted by plans that allowed high school seniors to take freshman level classes and by the growing number of junior colleges. On-campus enrollments suffered, often leading to reduced staffing. Deemed demeaning, the term “junior college” passed from use. The Arkansas Association of Two-Year Colleges was the title used by this twenty-two-member body. University faculty members were evaluated on the basis of teaching, research, and service, but two-year institutional staffs were hired only to teach.

Finally, the public’s perception was that higher education meant only one thing—better-paying jobs. “We cannot separate economic development and education,” Governor Mike Beebe proclaimed in 2007. Students were seen by the governor as customers. Thus, the core curriculum courses were constantly under attack from students as well those departments such as nursing and business. Because Arkansas higher education lacked the constitutional standing accorded public schools, issues of school finance had become a constant in legislative sessions and governors’ agendas.

In 2009, after a popular referendum on the matter, the state legislature created the Arkansas Scholarship Lottery, for which any Arkansas high school graduate enrolled full time at an Arkansas college is eligible. Beginning the fall of 2010, students attending a four-year college received $2,500 each semester, with those attending a two-year institution receiving $1,250. Due to decreased lottery ticket sales, those amounts were reduced by $250 in the fall of 2011. Initial reports show that approximately sixty percent of students renewed the scholarship after the first year. However, scholarship amounts were decreased again in 2013 and 2015 due to decreasing revenue. Another challenge to students, particularly lower-income students, is reduced state support for higher education, which means higher tuition at public institutions. Higher tuition forms a barrier to poor students, who then enter the workforce without the skills or knowledge they need for higher-paying jobs. This maintains a cycle of poverty and can further harm the already struggling economies of many areas of Arkansas and the South.

In February 2017, Governor Asa Hutchinson signed into law a bill linking state funding of colleges and universities to the percentage of students who complete their degrees, among other factors, a move some felt would cause budget difficulties at those institutions whose students are poorer and require more remedial education.

During the 2025 legislative session, the Arkansas General Assembly passed—and Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders signed—HB 1512, known as the Arkansas ACCESS Act (Acceleration, Common Sense, Cost, Eligibility, Scholarships, and Standardization), which Sanders promoted as offering higher education reforms comparable to the K-12 reforms in the LEARNS Act of 2023. The act prohibits state-supported institutions of higher education from collecting and reporting information relating to DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion), even if required for purposes of institutional accreditation. The act also made it illegal for state institutions to offer excused absences to students engaged in protest or advocacy, including such attempts to influence state legislation as testifying before a legislative committee. The ACCESS Act also expanded various scholarships offered by the state.

Conclusion

Over the past 200 years, higher education has moved from being a non-issue into one of the basic concerns of state finance as well as a major issue for families. For all these years, a consensus on what constitutes good education or how to pay for it has been elusive. These concerns have only increased in the twenty-first century.

The following chart lists Arkansas institutions of higher education, both current and defunct, on which the Encyclopedia of Arkansas has entries.

For additional information:

Arrington, Michael E. Ouachita Baptist University: The First 100 Years. Little Rock: August House, 1985.

Bledsoe, Bennie G. Henderson State University: Education since 1890. 2 vols. Houston: D. Armstrong Co., Inc., 1986.

Blevins, Brooks. Lyon College: The Promise and Perseverance of an Arkansas College. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Cobb, William H. Radical Education in the Rural South: Commonwealth College, 1922–1940. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2000.

Dew, Lee A. The ASU Story: A History of Arkansas State University, 1909–1967. Jonesboro: Arkansas State University Press, 1967.

Hall, John G. Henderson State College: The Methodist Years, 1890–1929. Arkadelphia, AR: Henderson State College Alumni Association, 1974.

Kennedy, Thomas C. “The Society of Friends and Black Education in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 42 (Autumn 1983): 207–238.

Jones, Virgil L. “John Clinton Futrall, University Builder.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 16 (Summer 1957): 97–116.

Klein, Arthur J., et al. Survey of State-Supported Institutions of Higher Learning in Arkansas. Bulletin No. 6. Washington DC: United States Department of the Interior, Office of Education, 1931.

Leflar, Robert A. The First 100 Years: Centennial History of the University of Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Foundation, Inc., 1972.

Lester, James E., Jr. Hendrix College: A Centennial History. Conway, AR: Hendrix College Centennial Committee, 1984.

———. The People’s College: Little Rock Junior College and Little Rock University, 1927–1969. Little Rock: August House, 1987.

Luck, H. D. Arkansas Higher Education, 1971–1995. San Antonio: The Watercress Press, 1996.

Meriwether, Robert W. Hendrix College: The Move from Altus to Conway. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Co., 1976.

Morgan, Gordon D. Lawrence A. Davis: Arkansas Educator. Millwood, NY: Associated Faculty Press, 1985.

Ostrander, Rick. Head, Heart, and Hand: John Brown University and Modern Evangelical Higher Education. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Pratt, Timothy. “Poor and Uneducated: The South’s Cycle of Failing Higher Education.” The Atlantic, August 25, 2016. Online at http://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2016/08/the-failures-of-southern-universities/497102/?utm_source=atltw (accessed September 27, 2022).

Shinn, Josiah H. Higher Education in Arkansas. Contributions to American Educational History, No. 26; U.S. Bureau of Education Circular of Information, No. 1. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1900.

Sparkman, James T., et al. Comprehensive Study of Higher Education in Arkansas. N.p.: Commission on Coordinating Higher Education Finance, 1968.

Startup, Kenneth M. The Splendid Work: The Origins and Development of Williams Baptist College. Walnut Ridge, AR: Williams Baptist College, 1991.

State-Controlled Higher Education in Arkansas. N.p.: 1951.

Walker, Kenneth R. History of Arkansas Tech University, 1909–1990. Russellville: Arkansas Tech University, 1992.

Wheeler, Elizabeth C. “Isaac Fisher: The Frustrations of a Negro Educator at Branch Normal College, 1902–1911.” Arkansas Historical Association 41 (Spring 1982): 3–50.

Willis, James F. “The Farmers’ Schools of 1909: The Origins of Arkansas’s Four Regional Universities.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 65 (Autumn 2006): 224–249.

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.