calsfoundation@cals.org

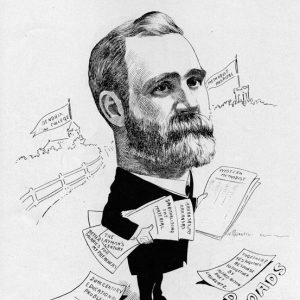

Alexander Copeland Millar (1861–1940)

Alexander Copeland Millar was a prominent Methodist minister, educator (elected one of the nation’s youngest college presidents), and publisher.

Alexander Millar was born May 17, 1861, in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, to William John Millar and Ellen Caven. His father engaged in the drug business in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, until the great fire of April 10, 1845, destroyed at least one third of the city, including his drug business and his family’s home. Later, William Millar tried his hand at being an inventor. In 1867, he moved his family to Missouri, where he bought a farm near Brookfield in Linn County. In 1885, Alexander Millar graduated from the Methodist-affiliated Central College in Fayette, Missouri. Four years later, he earned an MA from Central College. Millar received honorary doctorates from Wesleyan College (Kentucky) in 1907, the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) in 1922, and Hendrix College in Conway (Faulkner County) in 1940.

Millar married Elizabeth Harwood on June 27, 1887; they had three children. In 1924, Elizabeth died, and he married Susie McKinnon, a professor and author from Jacksonville, Texas, on October 15, 1925.

Millar’s first teaching job was with the private Brookfield Academy in Missouri, where he taught English and German while attending Central College. At Central, he studied Greek, Latin, and mathematics. Millar moved to Texas in 1885 and taught at Grove Academy in Dallas, Texas. However, citing a dislike for Grove Academy and for life in Texas, Millar resigned in January 1886 and returned to Missouri. That year, he accepted a professorship at Neosho Collegiate Institute (NCI), teaching math, ethics, logic, and bookkeeping. Soon after, he was elected NCI’s president and became one of the nation’s youngest college presidents. In 1887, he became president of Central Collegiate Institute in Altus (Franklin County), where he played a major role in changing the school’s name to Hendrix College and moving it to Conway in 1890.

In 1889, Millar toured U.S. colleges to find ways to improve instruction. The tour shaped his ideas about higher education, as evidenced by his 1901 book, Twentieth-Century Educational Problems. Describing himself as a “practical idealist,” he promoted uniform ideals among the state’s institutions of higher education. He was elected president of the Arkansas Education Association in 1911.

Millar was ordained a Methodist minister in 1888. He supported overseas missions and moral behavior and opposed the direct election of U.S. senators, Sunday baseball, liquor sales, gambling, and divorce. He only nominally supported efforts to prohibit the teaching of evolution in public schools. Although he never held a pastorate in Arkansas, he served in several church administrative positions, including presiding elder of the Morrilton (Conway County), Little Rock (Pulaski County), and Arkadelphia (Clark County) districts; delegate to Southern Methodism’s General Conference; and delegate to the commission that selected the name and site of the Western Methodist Assembly at Mount Sequoyah in Fayetteville. In 1934, he was elected to the Judicial Council of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. As a member of the executive board of the Federal Council of Churches, he supported the reunion of the Southern and Northern branches of the Methodist Church.

Millar was an advocate of the conservation and development of the state’s natural resources and improvements in its railroads and highways. He was chairman of the state’s first Good Roads Convention. His activities helped lead to the state constitutional amendment authorizing counties to levy road taxes. Later, he was appointed to the state forestry commission.

In 1902, Millar left Hendrix to become a professor at Central College. Two years later, he returned to Arkansas and bought the Arkansas Methodist with his friend, Dr. James A. Anderson of Little Rock. For nearly ten years, he was associate editor and business manager. During this time, he composed “My Own Loved Arkansas,” a song approved for use in public schools. In 1908, the Arkansas Penitentiary Board appointed him to investigate conditions at the Cummins prison farm; the legislature later enacted many of his recommendations. Governor George W. Donaghey, a close friend, appointed him to the first executive board of the Arkansas History Commission (now called the Arkansas State Archives).

In 1910, Millar celebrated his return to Hendrix, as president, by composing “Hendrix, O Hendrix.” In 1914, he became president of Oklahoma Methodist College, which was to be in Muskogee, but, partly because of the outbreak of World War I, the college never opened. In late 1914, he returned to Little Rock and became editor-in-chief of the Arkansas Methodist, a position he held until his death. He was twice elected president of the Southern Methodist Press Association.

An organizer of Arkansas’s Anti-Saloon League, Millar was president from 1925 until his death. In 1928, he sought the Democratic nomination for lieutenant governor. He dropped out when Democrats nominated Governor Alfred E. Smith of New York, an Irish Catholic anti-Prohibitionist, for president. Although a lifelong Democrat, he helped organize Arkansas Democrats, called anti-Smith Democrats, opposed to the ticket of Smith and Arkansas’s popular senior senator, Joseph T. Robinson, and urged them to vote for the Republican candidate Herbert Hoover. Five years later, he played a major role in leading “dry” Democrats who opposed the repeal of Prohibition.

In his final years, Millar continued to preach, visiting churches around the state, edited the Arkansas Methodist, and continued to fight for Prohibition and moral behavior. He died on November 9, 1940, in Little Rock and is buried in Oak Grove Cemetery in Conway.

For additional information:

Alexander Copeland Millar Papers. Arkansas United Methodist Archives. Bailey Library. Hendrix College, Conway, AR.

Lester, James. Hendrix College: A Centennial History. Conway, AR: Hendrix College Centennial Committee, 1984.

Rothrock, Thomas. “Dr. Alexander Copeland Millar.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 22 (Autumn 1963): 215–223.

Strickland, Michael Richard. “‘Rum, Rebellion, Racketeers, and Rascals’: Alexander Copeland Millar and the Fight to Preserve Prohibition in Arkansas, 1927–1933.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 1993.

Williams, Nancy A., ed. Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Michael Strickland

Arkansas State Library

Education, Higher

Education, Higher Mass Media

Mass Media Music and Musicians

Music and Musicians Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Prison Reform

Prison Reform Religion

Religion Alexander Millar

Alexander Millar

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.