calsfoundation@cals.org

African Methodist Episcopal Church

The African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) was founded in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, after white Methodist Episcopalians at the city’s St. George Chapel forced those of African descent out of the congregation in 1787. This led to the dedication of the first AME chapel, Bethel AME, in 1794. However, the AME was not represented in Arkansas until 1863 after President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

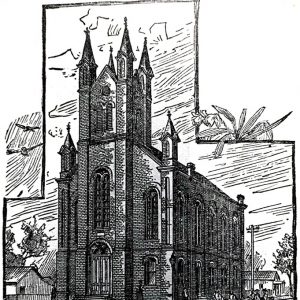

Arkansas’s earliest AME congregation formed under the leadership of the Reverend Nathan Warren. Warren, reared a slave in the District of Columbia, arrived in Arkansas in 1819 with Robert Crittenden, who served as the first secretary of the Arkansas Territory. Warren was later emancipated, after which he married and lived as a freedman and successful confectioner in Little Rock (Pulaski County) until 1856. Warren and other freedmen had to leave the state after groups such as the Mechanics’ Institute of Little Rock, a working-class white union, began agitating for the removal of free Blacks from the state. This helped along the passage of Act 151 of 1859, which banned non-enslaved African Americans from Arkansas. Warren and his family returned to Washington DC, where they lived until 1863, and Warren became involved with AME congregations there. When the family returned to Little Rock, Warren became the minister to a small group of African Americans in Little Rock and Helena (Phillips County) who had been worshiping as Methodists. This was the first AME congregation in the state. Three years later, the growing body began constructing the first church at the corner of 9th Street and Broadway in the heart of Little Rock’s Black community.

The church later known as Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church was dedicated as Campbell Chapel (named after Bishop Jabez Pitt Campbell) in 1875. Arkansas’s inaugural congregation placed service, education, and the social and political uplift of African Americans alongside its quest to minister to Black men and women’s spiritual needs. Under the direction of Little Rock Bethel AME Church, Bethel Institute (now Shorter College) was founded in 1886 to offer spiritual guidance, education, and opportunity to Arkansas’s Black students.

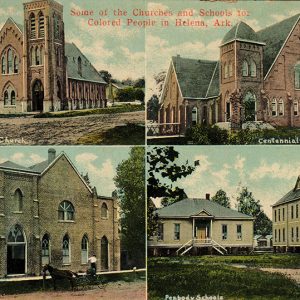

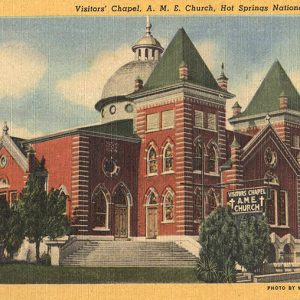

Bethel AME served as a springboard for other congregations to form across the state. Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) residents established St. John’s AME Church, while Helena citizens founded Carter’s Chapel in 1866, which became one of the largest AME congregations in the Delta. At Hot Springs (Garland County), residents established Visitors’ Chapel in 1870.

The growth of the denomination in Arkansas merited the establishment of annual state conferences and representation at the regional and national level. Under the direction of Bishop James A. Shorter, Arkansas became a destination for southern AME members and placed the state in a national spotlight. The first Arkansas Annual Conference was held on November 19, 1868. Four years later at the general conference in Nashville, Tennessee, the state was accepted into the Sixth Episcopal District. By the last decade of the nineteenth century, congregational growth demanded sectional state conferences that resulted in the establishment of the West Arkansas Annual Conference at Arkadelphia (Clark County) and the East Arkansas Annual Conference at Marianna (Lee County).

An 1890 national census showed that the AME Church in Arkansas included 333 churches and 27,956 members. Shorter’s direction had been an essential factor in earning Arkansas’s reputation as a bastion of AME leadership. The congregation of Little Rock Bethel AME Church worked to have Bethel Institute rededicated as Shorter University in 1892.

At the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, the AME Church in Arkansas remained committed to what Reverend Dennis Dickerson called a “liberationist” mission. This concept was particularly evident in the Jim Crow South. When racial tensions in the region escalated in the 1880s and 1890s, Arkansas’s AME leaders and assemblies performed mission work in Africa and were part of the Back-to-Africa Movement that was heavily promoted by southern African Americans for the purpose of establishing communities on that continent. AME leaders in Little Rock, Brinkley (Monroe County), and El Dorado (Union County), among other communities, raised tens of thousands of dollars for the movement and supported several individual missionaries during the last decades of the nineteenth century.

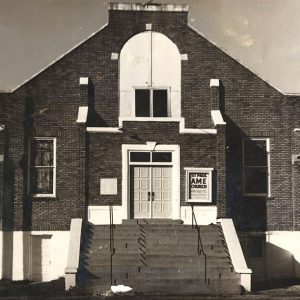

Growth continued, with smaller communities establishing their own congregations and Little Rock’s AME parishioners worshiping in several chapels, including St. Andrew’s AME Church, founded in 1905.

AME members continued to fight for social justice in the state and effect national change. Arkansas lawyer Scipio A. Jones, who successfully defended twelve Black men arrested after the 1919 Elaine Massacre and helped prevent a similar tragedy in Little Rock in 1927, belonged to the city’s Bethel AMEC congregation and was a graduate of the Bethel Institute. The AME Church was also an entrenched presence during the Little Rock Central High School desegregation crisis of 1957. Reverend Rufus K. Young Jr., who ministered at Bethel AME Church, supported the efforts of the Arkansas chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the leadership of AME member Daisy Bates. As president of the Arkansas NAACP, Bates became the face of the school desegregation movement in the state. In addition, several of the Little Rock Nine, students selected to integrate Little Rock Central High School, belonged to the AME Church and attended various churches within the city.

In the twenty-first century, the AME Church in Arkansas (a member of the AME Twelfth District) remains dedicated to its mission to care for the intellectual, physical, and environmental—as well as spiritual—needs of all people through its initial liberationist creed. The AME Church continues to offer faith-based education through Shorter College in North Little Rock (Pulaski County) and serve the people of Arkansas through approximately 150 congregations across the state.

For additional information:

12th Episcopal District of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. https://www.ame12.org/ (accessed October 30, 2025).

Barnes, Kenneth C. Journey of Hope: The Back-to-Africa Movement in Arkansas in the Late 1800s. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Lindsey, William, and Mark Silk. Religion and Public Life in the Southern Crossroads Showdown States. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press, 2005.

McSwain, Bernice Lamb. “Shorter College: Its Early History.” Pulaski County Historical Review 30 (Winter 1982): 81–84.

Ross, Margaret Smith. “Nathan Warren: A Free Negro of the Old South.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 15 (Spring 1956): 53–61.

“Visitor’s Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church: 1870–1995.” The Record 36 (1995): 75–79.

Misti Nicole Harper

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.