calsfoundation@cals.org

Business, Commerce, and Industry

Business, commerce, and industry in Arkansas developed with the help of Arkansas’s natural resources. In the twentieth century, former governor Charles Hillman Brough boasted that if Arkansas were walled off from the rest of the nation, it could exist independently due to the fertile soil, multitude of minerals, and wide variety of trees. In addition, Arkansas’s location in the central United States, which gives it access to navigable waters, intercontinental railroads, and interstate highways, helped integrate and encourage a wide variety of businesses, commercial enterprises, and industries. Despite the state’s external reputation for backwardness, it was at the forefront of prehistoric development and, in the twentieth century, became home to the world’s leading revolutionizing business force, Walmart Inc.

Prehistoric Period

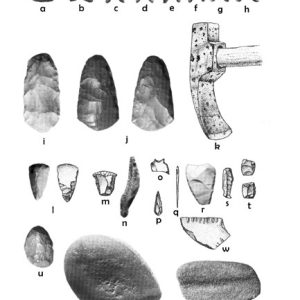

The prehistoric hunters who moved into Arkansas more than 10,000 years ago needed stone tools. Arkansas had suitable lithic materials everywhere except the Delta. Once a good stone source was found, bands visited the area and mined it. It was not necessary to go from rock removal to production of the finished point in one setting. Hence, pre-forms—semi-finished tools—were collected to be worked on at the band’s other migratory camps.

Because Native Americans retained their reliance on stone tools, the production of an increasing number of stone products—spear points, knives, adzes, hoes, and arrowheads—dominated Arkansas up to the eighteenth century. Novaculite served as the most important of these stone materials. The wide distribution of these items indicates that something of a national market existed, and the ones made in the Ouachita Mountains doubtless commanded the highest prices because of their rareness and beauty.

Other business activities consisted of trade in hides, furs, copper, seashells, and probably many ephemeral elements. The Quapaw were noted for the high quality of the buffalo robes they marketed, and the Caddo were also active traders in smoked buffalo meat and salt they obtained by boiling water from salt springs. By the protohistoric period, the Tunica tribe, some of whose members lived in southeast Arkansas, had developed a reputation as traders. Tribe members facilitated the transfer of goods between tribes on the Great Plains and the more settled agricultural communities farther east. The Spiro Site, just west of Fort Smith (Sebastian County), seems to have long been the locus of a large trade. Accounts from the Hernando de Soto expedition indicate that “traders” were present in some of the villages. Through such trade, tools and food plants were introduced from Mexico.

Local industries also included basket making and pottery. Because designs and materials were specific to particular regions, there was less trade in these areas. The rise of agriculture led first to farmsteads, but after AD 1100, when warfare broke out, fortified towns, comparable to European city-states, predominated. Slavery helped supply field labor and later a commodity for trade with arriving Europeans. The Hernando de Soto expedition disrupted the region, and the resultant population loss ended much of the business activity.

Colonial Period

French explorers Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet investigated the Mississippi River in hopes of finding a northwest passage to the Pacific. They stopped at the Quapaw villages near the mouth of the Arkansas River, but their trip sparked further exploration by French-Canadian businessman René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle. His grant of trading privileges to Henri de Tonti led to the founding of Arkansas Post in 1686. De Tonti found the place unprofitable, primarily because of the cost of shipping the hides and furs to Canada. Nevertheless, the post resulted in the Quapaw and other tribes becoming partners in a trans-Atlantic market system. This led them to abandon most of their traditional crafts and skills, as firearms superseded bows and arrows; iron pots and pans replaced pottery products; and European food, housing, and clothing came to predominate.

The post’s fortunes improved when the French secured the mouth of the Mississippi, permitting its products to move downstream to New Orleans, Louisiana, which became a thriving river port. Arkansas Post passed briefly to French banker John Law in the 1720s. His visionary development scheme rested largely on the assumption that mineral riches existed up the Arkansas River. Neither gold nor extensive rare gems were found, although the place name of Crystal Hill, now in North Little Rock (Pulaski County), reflects this legacy. Another legacy from the Law colony was the settlement of the first farmers near Arkansas Post.

In the eighteenth century, the Quapaw hunted near the Arkansas and White rivers, putting them into competition with the larger Osage tribe. Desultory violence lasted until both tribes eventually were moved west. The Caddo in southwest Arkansas were engaged in trade, primarily in horses, which they imported from the Plains tribes and sold to the eastern ones. They, too, were victims of Osage aggression. The Osage not only burned the Caddo villages on the Red River but stole horses from Europeans in Missouri and Arkansas and from every other adjacent tribe. Hides shipped from the post to New Orleans once constituted a salary inducement for Arkansas Post commandants, but trade declined, largely because of a combination of overhunting and Osage aggression. The buffalo robes that ended up in the Musée de l’Homme in Paris, France, probably were made as souvenirs to celebrate the Quapaw alliance with the French.

In the last decade of Spanish rule, Arkansas Post failed to develop as a major stopping point between St. Louis, Missouri, and New Orleans because it was too far upstream. But the presence of the garrison and government officials and some continuing trading sustained some business activity. Among other occupations, the Spanish census of the Post’s inhabitants listed “seamstresses”—a euphemism for prostitutes.

Early American Trading and Commercial Activities

By the 1790s, Euro-Americans brought cattle to Arkansas. The main commercial value was for the hides, so tanneries, first at home and then as commercial establishments, arose. The strong chemicals polluted soil and leached into water. One nineteenth-century promoter at Camden (Ouachita County) marketed waters from Bustin’s Celebrated Mineral Well, but the water’s unique flavorings were alleged to have come from an old tannery.

The nineteenth century also brought a greatly increased demand for salt, the essential ingredient in preserving meat (primarily pork). Salt was found in springs and boiled in kettles. Twelve important salt springs (salines) were identified in government surveys, and private parties were permitted only to lease the springs. John Hemphill’s Blakelytown salt works near Arkadelphia (Clark County) in 1811 was the earliest, but the richest source of salt was west of Fort Smith (Sebastian County) where Mark and Richard Bean made extensive use of slave labor in their operation. After these lands became home to the Cherokee, the Beans were dispossessed. They then used their slaves and federal compensation to open a cotton factory near Fayetteville (Washington County). The extent of Euro-American pioneers’ dependence on salt can be seen in several ways. The road from the Missouri River to the White River was known as the Salt Road; and using the word “saline” in naming creeks, counties, and towns suggested the presence of the mineral. Newer and cheaper production methods after 1840 led to the abandonment of the old boiling method before the Civil War, but during the conflict, desperate families congregated at the old springs. The sites most safely in use by the war’s end were along the Louisiana state line.

Fur and hides remained important enough after the Louisiana Purchase for the federal government to set up a factory (in the original meaning, the factor’s warehouse or store) at Arkansas Post. Under this system, the government gave tribal hunters fair prices and no liquor. At least one part-Cherokee trader, John Hill (a.k.a. Connetoo), fell afoul of the law by intercepting White River hunters. Additional factories operated at Spadra (Johnson County) and at the mouth of the Sulphur River in Miller County. The factory system was abolished in 1822, but by that time, the fur and hides frontier was closing in on the Rocky Mountains.

The emergence of Arkansas Territory coincided with the founding of the Arkansas Gazette. Despite ups and downs, suspensions, and sales, the newspaper continued operating until 1991. The first issue contained an assessment of Arkansas’s potential resources. In its lifetime, it promoted and publicized industrial development. Colonel M. L. de Mahler covered the state in the late nineteenth century, writing business reports, thus making him the first regular business writer.

The question of what natural resources might exist was a contentious matter. Governor Archibald Yell vetoed a bill to fund a state geological survey. Work finally began in the 1850s. David Dale Owen published two reports in 1858 and 1860 accompanied by valuable illustrations in his own hand. John C. Branner resumed work in the late nineteenth century, but his funding was cut when he reported that Arkansas did not have enough silver to warrant the silver boom that was in progress. Branner’s most important discovery was documenting the existence of bauxite, the ore from which aluminum was made, in 1891.

The discovery of important minerals led to the creation of a small but important mining industry. Lead mining began in the early 1800s on the Strawberry River in north-central Arkansas, but Newton County led in production. More than 20,000 pounds of ore were shipped out before 1860. Zinc, often discovered with lead, also found a market. The Independence Mining Company’s works at Calamine (Sharp County) consisted of three small mines and a smelter. Manganese mining began north of Batesville (Independence County) near present-day Cushman (Independence County) before 1860. The first coal shipments from Spadra started in 1841, but the irregularity of water levels on the Arkansas River hindered shipment. Coal expanded greatly after the arrival of railroads, with most of the mining being concentrated east of Fort Smith. Iron production started in 1850. Whetstone production started in the Ouachita Mountain area near Hot Springs (Garland County) in 1818.

Yell’s veto of the state geological survey reflected the belief that the new industrial age was neither needed nor wanted, although the state did create the Arkansas Geological Survey in 1857. Most items, including clothing, food, furniture, and tools, were made at home. These household manufacturers were supplemented by neighborhood industries such as gristmills, blacksmith shops, and the shops of artisan craftsmen. Poor transportation perpetuated the system into the 1880s.

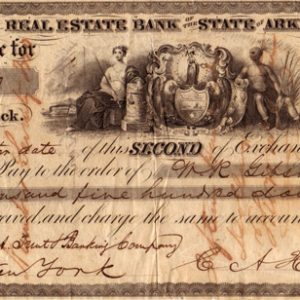

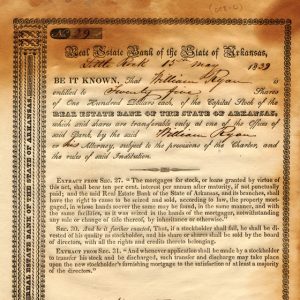

Late-twentieth-century economists described the precursors of industrial development as infrastructure. This term could refer to many items, all lacking in Arkansas. First, the state failed at its two experiments with public-funded banking. The Real Estate Bank (an early sort of savings and loan) and the State Bank suffered from bad timing—going into operation at the start of the worst depression America had experienced—and bad management, which included insider trading and fraud. The state was left liable for the debts, which, unpaid until the end of the nineteenth century, not only made the state technically bankrupt but soured the financial markets on the state’s very name. This bad reputation would return during the Great Depression when the state defaulted on its new highway debt.

Second, absence of a capital lending source retarded the establishment of such improvements as canals, toll roads, and railroads. No canals were built, but an early toll bridge over the Ouachita River at Rockport (Hot Spring County) fell victim to a flood in 1847 and was not rebuilt. Railroad construction issues dominated the 1850s, but the funding for the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad and the Cairo and Fulton line came from out-of-state sources.

Finally, the failure of the state to establish and fund public education resulted in a largely illiterate work force, although at a time when most employment was agricultural, the economic liability probably was limited.

In spite of the obstacles, a merchant class arose in the towns. Philadelphia, probably because of family connections, loomed large in supplying merchants, who typically made one trip east each year to arrange for merchandise. Scotch-Irish Presbyterians and Jews rose to prominence. Their response to the paroxysms of Southern nationalism that led to secession was best demonstrated then Mrs. Frederick Trapnall threw a bouquet to the unrepentant and embattled Unionist Isaac Murphy for voting “no” to secession.

Typically, the cry for modernization came from the Whig Party, but even Whig planters preferred to invest in land and slaves rather than industry. Pro-industrial sentiment came largely from newspapers. Perhaps the most conspicuous resource was water power, of which Arkansas had an estimated 1.255 million horsepower units. Before the Civil War, gristmills, mostly in the Ozarks, constituted the primary tapping of this resource.

The one conspicuous example of both problems and successes in establishing industry came from Henry Merrell’s mill complex at Royston (Pike County). Merrell used water to drive a saw, a gristmill, a flour mill, a cotton mill, and for carding wool and spinning thread. The county responded with a hate campaign claiming that he charged too much and was not sufficiently patriotic. During the Civil War, Merrill sold out and moved to Texas. The only other comparable establishment was a steam-powered 1,800-spindle cotton mill at Van Buren (Crawford County) that employed over thirty workers. It burned during the Civil War.

The Civil War prompted several enterprises. In the towns, women’s groups made uniforms with sewing machines. Home production of cotton depended on cotton cards, an item in short supply but produced by a factory in Camden at the rate of eight to twelve a day. Medicines, including blue mass and castor oil, were manufactured at Arkadelphia. Saltpeter, processed from bat guano found in Ozark caves, was one of the vital elements for making gunpowder, but guerrillas disrupted production. The section of the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad from DeValls Bluff (Prairie County) to what is now North Little Rock was completed in early 1862 but was used by Federal troops from 1863 to 1865. By war’s end, many towns were in ruins, and abandoned fields had begun to grow up in weeds. The war did not promote modernization in Arkansas as it did in the North.

Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century

The centerpiece of Republican Reconstruction was railroad promotion. Between 1865 and 1874, the first completed roads reached the state. From 1874 to 1910, railroads penetrated to all but one county, Newton County. In 1880, Arkansas had 859 miles of track; in 1915, the figure was 5,407. In the aftermath of this connectivity came the collapse first of cottage industries. Mass-produced hats, shoes, furniture, and other consumer items put local craftsmen out of business. Home industries took longer to extinguish, for only when rural residents had access to ready money could they buy rather than make or grow items. The rural country store offered cash or credit for such items as eggs, railroad ties, hides, and furs while offering steel-tipped plows, hardware, and canned goods. The extension of credit often was the first step for the storeowner to become the lord over sharecroppers. Indeed, in the Delta, most necessities came from the store or, as often it was styled, the plantation commissary. Fully ninety-six percent of the business was done in the last four months of the year (harvest time). Across the state, merchants typically closed one day a week. Rural shoppers went into town on Saturdays, and it was customary to stay open even to midnight to get the last dollar. Several small town merchants grew their businesses over the decades, becoming some of the first regional department store chains in the country. An example of this growth was the M. M. Cohn chain, founded in Arkadelphia in 1874 before moving to Little Rock before the end of the decade.

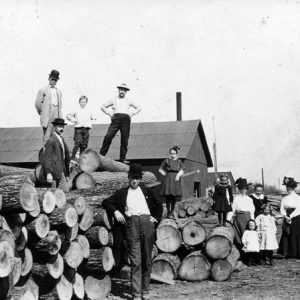

The greatest changes took place in timber. The first steam-powered sawmill opened in Helena (Phillips County) in 1827. Most mills until the 1870s were water powered, and an output of 5,000 board feet a day was considered exceptional. Transportation limitations meant most mills served buyers within twenty miles. Even by 1869, timber or related products far outranked all other industrial products. In the 1880s, as Northern forests were decimated, timber companies from Michigan, Illinois, and Iowa moved south. Sawmill towns arose along railroad lines, or timber companies built their own lines. In the first phase of activity, it was cut and run. Entire towns such as Graysonia (Clark County) disappeared almost overnight. Other sawmill towns, notably Crossett (Ashley County), endured as company-owned units until after World War II. By 1900, after the creation of drainage districts in the Delta, some companies began making land sales.

By 1909, the timber boom was over, and not until the 1920s did modern replanting methods ensure that the industry would endure. In 1909, seventy-three percent of Arkansas workers worked in the timber industry; by 1927, that had fallen to fifty-seven percent. After 1920, the industry was concentrated primarily in the Ouachitas and Gulf Coastal Plain; large areas of the Delta by the turn of the twenty-first century had become nearly treeless.

The movement toward industrialization had many obstacles. Arkansas had local deposits of minerals, but local production often was limited. The state had brick factories but not a brick industry. Bauxite, the state’s most important mineral, was mined and sent out of state to be fabricated. Even in timber, Arkansas was primarily a source of wood rather than home to a furniture industry. In some areas, nationwide monopolies doomed Arkansas’s ambitions. Cottonseed was monopolized at the expense of farmers; a similar fate befell local tobacco. Unfavorable rail rates that lasted until 1946 put Arkansas industries at a disadvantage in the national market. Indeed, national forces dictated that the South would remain a colonial economy.

By the 1880s, Arkansas was linked to the national economy. Town creation was virtually complete, and while there was enormous turnover in businesses, by 1910, many family businesses that would endure well into the twentieth century had taken root. Opposition to the modernization persisted, however, and culminated under then-governor Jeff Davis, who used the Rector Anti-Trust Act to drive fire insurance companies out of Arkansas.

Segregation led to the establishment of businesses to offer goods and services to the African American community. In smaller towns, some stores served all customers regardless of their race, but cities with larger populations supported entire districts of businesses to cater to African Americans. The West Ninth Street area in Little Rock contained more than 100 Black-owned businesses, as well as the headquarters of several African American fraternal organizations.

Early twentieth-century developments reflected a contrast between wildly exaggerated promotional claims and dry statistical refutation. Central to the promotionalist view was the notion that advertising could overcome Arkansas’s low statistical rankings in industry, income per capita, education level, public library expenditures, and the like. The first state nickname—“The Wonder State”—was adopted in 1923 after a promotional campaign led by former governor Charles H. Brough. He took to the premier national lecturing circuit, Chautauqua, with a message that emphasized every positive statistic and ignored fundamental realities. National critics, led by H. L. Mencken, responded with jeers and jokes. Other campaigns came in the late 1930s, mid-1940s, and thereafter about every five to ten years as Arkansas became successively “The Land of Opportunity” and “The Natural State,” although the state’s national rankings generally remained static.

The new century also saw new commercial developments. The two most important were utilities and petroleum. Electricity was virtually synonymous with Harvey Couch, founder of Arkansas Power and Light (AP&L). After creating a small telephone network in areas ignored by the Bell system and then selling out, he began buying small local electric companies that often provided minimal service; he built hydroelectric dams and, to ensure his profits, had the legislature create a state utilities commission that allowed him to raise rates almost at will. Couch’s politics created much resentment. The collapse of a national utility holding company during the Depression helped spur the New Deal’s Rural Electrification Administration (REA), thus initiating a bitter war between co-ops and AP&L. Not until after 1945 was more than half the state served with electricity. A few communities, notably Jonesboro (Craighead County) and Paragould (Greene County), held out against AP&L, and their economic success in the late twentieth century was greatly influenced by their substantially lower utility rates.

Petroleum became important when the Busey No. 1 Well, the first profitable oil well in the state, came in on January 10, 1921, near El Dorado (Union County). From having no oil in 1920, the state rose to fourth place in 1926, but its rank declined precipitously. The absence of state regulation resulted in waste and fraud. The severance tax, the commonly applied tax on diminishable natural resources, was first long delayed and then pitifully low in comparison with other states. The first local company to emerge with regional visibility was Lion Oil. Its founder, Thomas Harvey Barton, was a state political figure, sponsor of the state fair, and promoter of cattle production.

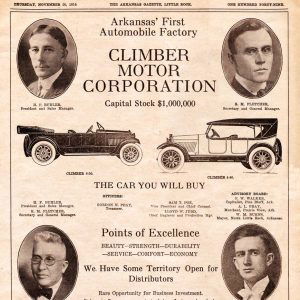

Two petroleum-related industries were represented in Arkansas. The Climber Motor Company in Little Rock turned out automobiles and trucks between 1919 and 1924. Command-Aire, an airplane factory founded in 1926, at its height employed 290 workers and turned out an airplane a day, until the Depression killed its market.

Unions appeared even before the Civil War. Officially, the first nationally recognized union was created by the typographers who manned presses. Other unions followed in railroads, coal mining, and even agriculture. The radical International Workers of the World (IWW, a.k.a. the “Wobblies”) appeared prior to World War I, but the 1920s ushered in a strong anti-union movement both state-wide and nationally.

The war had a positive impact on the infrastructure in the state, with several facilities constructed by the federal government, which in turn supported private industries. These sites included the Little Rock Aviation Supply Depot and the Little Rock Intermediate Air Depot, which evolved into the Bill and Hillary Clinton National Airport. Business leaders in Pulaski County led an effort to construct a major army training facility in the state, which came to fruition with the establishment of Camp Pike in 1917, later renamed as Camp Joseph T. Robinson.

Despite progress, the state’s per capita wealth was half the national average in 1922. Some farmers benefited from the advent of canning factories after 1890. Because American agriculture was so dispersed, monopolization in this field was long delayed. Although larger canneries had to meet federal standards if their goods crossed state lines, local firms for decades avoided federal Pure Food and Drug laws by restricting their sales. Canning plants were all over the state, with the greatest concentration in the Ozarks, and tomatoes were “red gold” for farmers. More than 900 workers, mostly women, were employed in canneries in 1927. Companies such as Allens, Inc., prospered for decades with a strong local workforce and consistent supply of produce. Strawberries remained important until after World War II, and although apple production peaked in 1919, peaches and apples remained important for decades. In the early twenty-first century, two watermelon-producing areas, Cave City (Sharp County) and Hope (Hempstead County), labeled and marketed branded melons.

Such developments did not tend to benefit tenant farmers, and with each passing year, tenancy increased until half the state’s farmers were landless. Overwhelmingly, they were tied to one crop, cotton, and its price collapse at the start of the Depression nearly brought about revolution in the South.

The Great Depression

The Great Depression began in Arkansas in the wake of the drought of 1930, which cut farm income by sixty-two percent. Many small-town banks could not cope, and a wave of closures followed. The biggest hit was taken by Aloysius Burton Banks, who had created a statewide chain of more than fifty banks. The state’s leading financier of the 1920s went to jail while many towns and counties were left virtually without a credit system or even a circulating currency. The Helena Daily World was not the only newspaper that printed “scrip” (small denomination paper money) for local use.

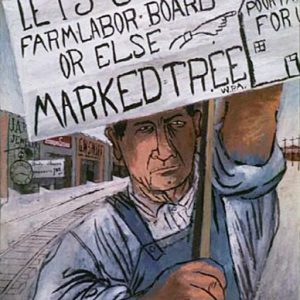

Arkansans welcomed the New Deal, but the Agricultural Adjustment Act, written to benefit landowners rather than tenants, not only failed to attain social justice but helped usher out the family farm. In the newly established quota system, small- and medium-size farms found their cotton allotment too small to be profitable. King Cotton, grown in every county, shrunk to a mere handful of counties in the Delta by 1980.

The hit taken by Arkansas industries would have received more attention had there been more industries. The state had almost 300,000 wage earners in 1929; the Depression cut that in half, and wages fell from almost $40 million in 1929 to $15 million in 1933. New Deal labor policies allowed unions, which had been driven out of the coalfields and kept out of lumber, to return to Arkansas. The Depression also devastated business not associated with agriculture, with many closing, including more than ten percent of the Black-owned businesses located along West Ninth Street in Little Rock.

World War II and Postwar Developments

Arkansas’s recovery late in the Depression was fueled in part by federal programs, including public works projects by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the Public Works Administration (PWA), and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). But even more development resulted from World War II.

Arkansas’s congressional delegation in 1941 lacked seniority, so Arkansas benefited comparatively little from wartime expenditures. Such expenditures created eighty-one percent of wartime jobs. Arkansas did receive a local boost from the wartime creation of various munitions production facilities that included the Southwest Proving Grounds outside Hope, the Incendiary Munitions Plant (later the Pine Bluff Arsenal) at Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), the Arkansas Ordnance Plant in Jacksonville (Pulaski County), and the Shumaker Naval Ammunition Depot in Ouachita and Calhoun counties, as well as the Jones Mills (Hot Spring County) and Hurricane Creek aluminum-processing plants in Saline County; the completion of Norfork Dam on the White River in Baxter County was also a boon. The state also benefited by the construction of multiple military airfields, with major locations at Walnut Ridge (Lawrence County), Camden, Helena (Phillips County), Pine Bluff, Newport (Jackson County), Blytheville (Mississippi County), and Stuttgart (Arkansas County). Smaller auxiliary airfields were constructed across the state to support the pilot training efforts based at the major airfields. Despite these projects, more than ten percent of the state’s population left, mostly for wartime jobs in the North and West.

Business interests used the conservative wartime atmosphere to again attack labor. Amendment 34, labeled as guaranteeing the right to work but better described as how to retard the growth of unions, was added to the state constitution in 1944. Arkansas joined other Southern states in promising Northern businesses a union-free environment, lax safety laws, low state minimum wages, and fiscal benefits for relocating. After workers at the Daisy plant rejected unionization in 1962, owner Cass S. Hough pronounced Arkansas’s industrial climate to be “ideal.” Typical of labor/management relations was the Singer plant in Trumann (Poinsett County), which manufactured wooden cases for sewing machines. The company told workers that if they unionized, it would close the plant. The threat worked, but in the early 1980s, the company closed it anyway and moved to Mexico.

Unionization, which had grown rapidly, stagnated. Fighting a rear-guard action was the state head of the AFL-CIO, Bill Becker, who for decades provided visibility for labor issues. Serious decline began in the Reagan administration. The timber industry began open warfare on unions. Georgia Pacific won a major victory at Crossett, replacing longtime workers with permanent strikebreakers. Another significant defeat took place at Forrest City (St. Francis County), where Sanyo employed some 1,800 workers.

By the 1950s, the Cold War generated an American military-industrial complex, and Senator John McClellan of Arkansas was one of the key national players. Governor Sid McMath had been a major supporter of Harry Truman in 1948, and the reelected Democrat returned the favor. One conspicuous example was the Little Rock Air Force Base (LRAFB), employing more than 16,000 workers in the mid-1980s. Additional dam construction included Greers Ferry and other lakes. McClellan’s greatest accomplishment was the McClellan-Kerr Navigation System, which made the Arkansas River navigable year-round to Catoosa, Oklahoma.

Arkansas’s industry recruitment efforts received a major boost when Winthrop Rockefeller decided to settle on Petit Jean Mountain in Perry County. Not only did he encourage better cattle production, but he served as head of the Arkansas Industrial Development Commission (now the Arkansas Economic Development Commission) and later became governor of the state.

Meanwhile, Arkansas continued to lose population. As machines replaced people, depopulation, often up to ninety percent, occurred in the plantation areas. The small towns dependent on the cotton trade faded. Often, the efforts of residents to set up an industrial park or lure industry were frustrated by landowners who opposed change for fear that industries would pay competitive wages and thus lure away their workers. The Delta started dying, a process that continued into the twenty-first century. The upper Delta counties, which were less a part of the plantation system, fared better. Jonesboro had Arkansas State College (now Arkansas State University) and the low electricity rates from its municipally owned utility. Paragould, too, had locally owned power. In the early 1950s, many shoe and textile factories moved to the region, providing low-paying jobs, predominately for women.

Electricity—ubiquitous after 1950—resulted in the brief rise of a dairy industry and the sustained growth of chicken (broiler) production. By the start of the twenty-first century, chicken was the state’s top agricultural product. Tyson Foods was virtually synonymous nationwide with this industry. The actual raising of chickens was done by contracting with landowners, who sometimes came to the conclusion that they were but modern sharecroppers due to their limited freedom and income. The most important part of the company’s profit came not from sales of raw chickens but from “valued-added” processing that included de-boning and pre-cooking. In addition, the company branched out into pork and cattle production. Meanwhile, only rice received much “valued-added” processing in Arkansas; cotton and soybeans were mostly exported raw.

Arkansas’s march toward the average national income level was stunted by bad press from the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock. But, by the late 1960s and early 1970s, Arkansas was surging forward again. Examples were Stephens, Inc., the largest off–Wall Street brokerage; Tyson, synonymous with chicken but also pork and beef products; TCBY, a frozen-yogurt company that made a brief splash with Wall Street traders; several trucking companies (P. A. M. Transportation Services, Inc.; J. B. Hunt’s Transport Services, Inc.; American Freightways); Alltel in telecommunications (until it merged in January 2009 with Verizon Wireless, based in New Jersey); Murphy Oil in El Dorado; and Dillard’s, a national department store chain. Arkansas was even home to Daisy, Cass Hough’s air-rifle company, headquartered at Rogers (Benton County). Although Arkansas ranked low in Internet usage, Little Rock was home to Acxiom: a data management company founded in 1969; it became, over time, an international presence.

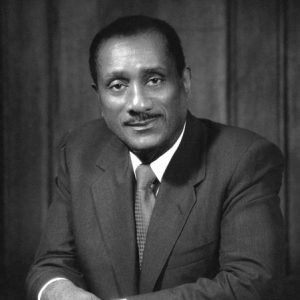

A series of publications have recorded Arkansas’s business activity. One of the first was the Rural and Workman newspaper in the 1880s. Colonel M. L. De Malher served as the state’s chief industrial promoter in the late eighteenth century. Working for the Arkansas Gazette between 1883 and 1898, he walked to every county in the state, producing long technical reports published under the name “Potomac.” During the 1950s and 1960s, the Arkansas Almanac provided much industrial promotion material. By the 1980s, business activity reached a level sufficient to support a weekly newspaper, Arkansas Business, which later added a northwestern Arkansas edition. The Arkansas Business Hall of Fame, established in 1999, presented a cross section of business leaders; for a long time, the only African American inductee was John H. Johnson, the founder and publisher of Ebony and other magazines, but it has since expanded. Arkansas, however, remained best noted for Walmart Inc. founder Sam Walton.

Modern-day Developments

The much-told Walmart Inc. story focused on how a displaced storeowner in Newport (Jackson County) moved to Bentonville (Benton County) and founded a discount chain. That chain not only swamped its competitors but became the world’s largest retailer after its founder’s death in 1992. Walmart Inc. probably led the nation in hostility to unions, supporting a secret union-spying operation. It called its workers “associates” even though the majority of them worked less than a forty-hour week (and therefore were ineligible for medical coverage, stock options, etc.). Its small-town critics called it a “town killer” because local business districts were decimated once a Walmart Inc. store opened outside town. During Walton’s life, the annual shareholder meeting in Fayetteville (Washington County) resembled more a religious revival than a business meeting. Walmart Inc. became a polarizing example of modernization and change in retailing, either glorified as the “most admired company” or damned for its labor relations and perceived negative impact on local communities. Curiously, outside of the newspaper industry in Arkansas, which lost its advertising to Walmart Inc.’s own in-house printing plant, the controversies made little impact in the state of Walmart Inc.’s genesis. Both Tyson and Walmart Inc. stayed in Arkansas, while a Little Rock firm, Federal Express, moved to Memphis.

Arkansas ended the twentieth century with an outmoded industrial program. All over the nation, companies were fleeing offshore. Almost overnight, textiles, shoes, and thousands of other industrial jobs disappeared. Reductions or disappearances took place in the aluminum-processing industry, Camden’s Cold War–related jobs, and Fort Smith’s appliance jobs. Whirlpool in Fort Smith employed some 4,800 workers during the peak summer of 1995; about 2,000 jobs were gone by 2006, and Whirlpool, having purchased Maytag, shuttered the Searcy (White County) Maytag plant, formerly with 600 jobs, the largest employer in White County.

Retarding Arkansas’s development was the attitude of many of its citizens, some of whom felt that a high school diploma was not necessary to secure a job. In addition, much vocational preparation was directed at jobs already headed overseas. Given its small town and rural nature, Arkansas was ill prepared for the Information Age. The 2002 State New Economy study gave Arkansas an overall rank of forty-eighth in the nation. Ironically, the state government ranked twenty-fourth in digital technology and even thirtieth on a weighted measure of computer and Internet use in the schools, but the state stood dead last—fiftieth—in the level of workforce education, forty-ninth in information technology jobs, forty-ninth in patents, and forty-eighth in scientists and engineers.

Deregulation was a major part of the new order that arose in the 1970s. The transitions in industry were not smooth. First came airline deregulation in the 1970s; virtually every firm in business then is gone now. A similar chaos hit banking in the 1980s. Within ten years, nearly every established bank was gone. One new bank, First Commercial, the work of William H. Bowen, emerged from the chaos, but it was sold to an out-of-state firm, Regions (formerly Alabama Bankshares). Examples of growth followed by buyouts became the norm at the end of the twentieth century. The New Federalism promised states more control, but in banking in particular, federal laws robbed the states of their traditional regulatory role. State government grew, becoming Arkansas’s largest employer. Reflective of an important Arkansas business, the three highest paid state employees at one time were coaches at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville.

Not all modern-day industries could take advantage of the new environment and move offshore or to Mexico. Two pillars of the food-processing industry, Nestlé and Frito-Lay, were lured to Jonesboro with multimillion-dollar state support; a micro-steel plant at Barfield (Mississippi County) succeeded; and a surprising tourist draw was the William J. Clinton Presidential Center and Park in Little Rock. Arkansas was over-represented by an aging population, and had two percent more smokers than the national average of twenty-three percent. At the same time, the number of uninsured kept rising, from 391,594 in 2001 to 455,798 in 2004. Medical services were badly hit by the closing of rural and small-town hospitals caused by a Reagan-era policy that paid proportionately more to urban medical centers. Arkansas had one claim to national recognition in this field with Arkansas Children’s Hospital, specializing in burn cases. Less revered was the state’s nursing home industry. Fraud and neglect lawsuits followed Fort Smith’s Beverly Enterprises, which in early 2006 was sold to GGNSC Holdings. In 2001, damages of $78 million (later reduced) were assessed against Rich Mountain Nursing Home in Mena (Polk County) for its neglect of an elderly patient.

In the first decades of the twenty-first century, outdoor recreation grew into an outsized portion of the state’s economy. With multiple national and state parks, Arkansas attracts visitors for hiking, cycling, boating, and other activities, the area is an important economic driver. Amendment 75, passed in 1996, designates 1/8 cent of the state sales tax to be utilized for conservation and recreation purposes, providing the state funding to support state parks and the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission.

Growth in other types of recreation also drive the economy of the state in the early twenty first century. Breweries and distilleries have always played a role in the food and beverage market in the state, but an explosion of growth in that area began around 2000 and continues in 2024. Well known business such as Diamond Bear Brewery and Rock Town Distillery help lead the charge. In 2016, state voters approved the sale of cannabis in Arkansas for medical purposes, although efforts to approve recreational have failed. Gambling, a popular past time even during colonial times in Arkansas, has also experienced growth in the first two decades of this century. Long popular past times like horse racing have now been joined by a variety of other betting opportunities. Thanks to a 2008 ballot initiative, a statewide lottery began operations. Voters approved Amendment 100 in 2018 to allow the creation of four casinos in the state. This led to Oaklawn Park Racetrack and Southland Greyhound Park to add games of skill and adopt new names. The amendment also approved the addition of new casinos in Jefferson and Pope counties, although a long running legal battle in the latter jurisdiction has prevented any meaningful progress to be made on that project, while Saracen Casino now operates in Pine Bluff.

An overview of Arkansas in 2006 revealed enormous growth (and growth-related problems) in the economy and population of northwest Arkansas; a lesser but significant amount of development outside of Little Rock in its predominately white suburbs; surprising growth in the Jonesboro/Paragould corridor; and stagnation or decline throughout the rest of the state. This trend continues in 2024, despite economic development efforts across the state. Major business development continues in central Arkansas, northwestern Arkansas, and in a few counties in the northeast. Scattered projects are located in other counties, with many areas of the state, especially much of the Delta, southwestern Arkansas, and north-central Arkansas seeing little economic investment.

For additional information:

“150 Years of Arkansas Business.” Arkansas Business, June 30, 1986.

Arkansas Scrip Collection. Old State House Museum Online Collections. Scrip Collection (accessed August 11, 2023).

Balogh, George W. Entrepreneurs in the Lumber Industry: Arkansas, 1881–1963. New York: Garland Pub. Co., 1995.

Barber, Melvin C. “Change in the System of Central Places of the St. Francis Region.” PhD diss., Southern Illinois University, 1971.

Duvall, Leland, ed. Arkansas: Colony and State. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Co., 1973.

Griner, James Emmett Pool. “The Growth of Manufacture in Arkansas, 1900–1950.” PhD diss., George Peabody College for Teachers, 1958.

Rosenberg, Leon Joseph. Dillard’s: The First Fifty Years. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1988.

Besom, Robert D. “Little Rock Businessmen Invest in Coal: Harmon L. Remmel and the Arkansas Anthracite Coal Company, 1905–1923.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 47 (Autumn 1988): 273–287.

Blakely, Jeffrey A. “The Nineteenth Century Pottery Industry in Sebastian County.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 49 (Spring 1990): 57–77.

Buckalew, A. R., and R. B. Buckalew. “The Discovery of Oil in South Arkansas, 1920–1924.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 33 (Autumn 1974): 195–238.

Faulkner, Ed. “The Climber: A Chapter in Arkansas Automotive History.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 29 (Autumn 1970): 215–225.

Flemmons, Kenn. “Little Rock Brewery & Ice Company.” Pulaski County Historical Review 70 (Spring 2022): 18–25.

Galchus, Kenneth E., Charles G. Martin, and Ashvin P. Vibakar. “A History of Usury Law in Arkansas, 1839–1990.” University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review 12 (1989–1990): 695–737.

Griffen, Richard W. “Pro-Industrial Sentiment and Cotton Factories in Arkansas, 1820–1863.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 15 (Summer 1956): 125–139.

Halpern, Martin. “Arkansas and the Defeat of Labor Law before 1978 and 1994.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 57 (Summer 1998): 99–133.

Littlefield, Daniel F. “The Salt Industry in Arkansas Territory, 1819–1836.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 32 (Winter 1973): 312–336.

Merrell, Henry. The Autobiography of Henry Merrell: Industrial Missionary to the South. Edited by James L. Skinner III. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1991.

Minchin, Timothy J. “Torn Apart: Permanent Replacements and the Crossett Strike of 1985.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 59 (Spring 2000): 31–58.

Orejel, Keith. “Factories in the Fallows: The Political Economy of America’s Rural Heartland, 1945–1980.” PhD diss., Columbia University, 2015.

Pitcaithley, Dwight. “Zinc and Lead Mining along the Buffalo River.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 37 (Winter 1978): 293–305.

Quinn, Bill. How Wal-Mart is Destroying America and the World and What You Can Do About It. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press, 2001.

Ritgerod, Henry A. A History of Capital Stock Insurance in Arkansas. Little Rock: Association of Insurance Agents, 1952.

Schwartz, Marvin. Tyson: From Farm to Market. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991.

Smith, Kenneth L. Sawmill: The Story of Cutting the Last Great Virgin Forest East of the Rockies. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1986.

Smith, Shanika. “The Success and Decline of Little Rock’s West Ninth Street.” Pulaski County Historical Review 67 (Summer 2019): 41–50.

Spier, William. “A Social History of Manganese Mining in the Batesville District of Independence County.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 36 (Summer 1977): 130–157.

Switzer, Ronald R. Arkansas, Forgotten Land of Plenty: Settlement and Economic Development, 1540–1900. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2019.

Trimble, Vance. Overnight Success: Federal Express and Frederick Smith, Its Renegade Creator. New York: Crown Publishing Co., 1993.

Vance, Sandra S., and Ray V. Scott. “Sam Walton and Wal-Mart Stores, Inc.: A Study in Modern Southern Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Southern History 58 (May 1992): 231–252.

———. Wal-Mart: A History of Sam Walton’s Retail Phenomenon. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1994.

Veasey, R. Lawson, and Kent L. Oots. “Citizen Opinion: The Future of the Arkansas Economy.” Arkansas Business and Economic Review 24 (Fall 1991): 1–5.

Willis, James F. “Antitrust in Arkansas Politics during the Progressive Era.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 80 (Winter 2021): 436–467.

Worley, Ted R. “The Arkansas State Bank: Ante-bellum Period.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 22 (Spring 1964): 65–73.

———. “The Batesville Branch of the State Bank, 1836–1839.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 6 (Autumn 1947): 286–299.

———. “Control of the Real Estate Bank of the State of Arkansas.” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 37 (December 1950): 403–426.

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Revised 2024 by David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Former Acxiom Corporation Headquarters

Former Acxiom Corporation Headquarters  Arkansas Business Hall of Fame

Arkansas Business Hall of Fame  Arkansas Children's Hospital

Arkansas Children's Hospital  Arkansas Power & Light (AP&L) Ad

Arkansas Power & Light (AP&L) Ad  Arkansas Real Estate Bank Draft

Arkansas Real Estate Bank Draft  Arkansas Real Estate Bank Stock Certificate

Arkansas Real Estate Bank Stock Certificate  T. H. Barton

T. H. Barton  Bauxite, Official State Rock

Bauxite, Official State Rock  John Casper Branner

John Casper Branner  Clarendon Button Factory

Clarendon Button Factory  Climber Motor Corporation Ad

Climber Motor Corporation Ad  Clinton Presidential Library and Museum

Clinton Presidential Library and Museum  Corner Cafe

Corner Cafe  Harvey Couch

Harvey Couch  Dalton Period Artifacts

Dalton Period Artifacts  Henri de Tonti

Henri de Tonti  Devil's Den State Park

Devil's Den State Park  Dillard's, Inc., Headquarters

Dillard's, Inc., Headquarters  Dryden Pottery

Dryden Pottery  El Dorado Oil Rig

El Dorado Oil Rig  Harrison First Passenger Train

Harrison First Passenger Train  Hartz-Thorell Seed-Processing Plant

Hartz-Thorell Seed-Processing Plant  Hunter Sawmill

Hunter Sawmill  Hunterville

Hunterville  I. W. Carpenter Store

I. W. Carpenter Store  J. B. Hunt Intermodal Service

J. B. Hunt Intermodal Service  J. B. Hunt, Aerial View

J. B. Hunt, Aerial View  John H. Johnson

John H. Johnson  Judsonia Hat Shop

Judsonia Hat Shop  Judsonia Strawberry Wagons

Judsonia Strawberry Wagons  Kraft-Phenix Cheese Factory

Kraft-Phenix Cheese Factory  Lest We Forget by Ben Shahn

Lest We Forget by Ben Shahn  LRAFB Grand Opening

LRAFB Grand Opening  M. M. Cohn Department Store

M. M. Cohn Department Store  Marshall Strawberry Pickers

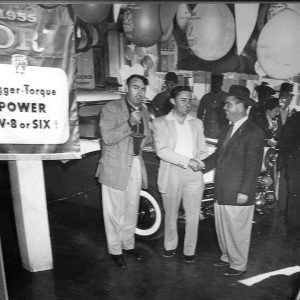

Marshall Strawberry Pickers  Frank McLarty at Dealership

Frank McLarty at Dealership  Harry Mitchell

Harry Mitchell  Moore Motor Company

Moore Motor Company  Charles Murphy

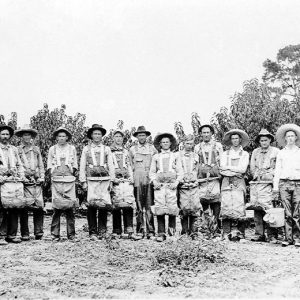

Charles Murphy  Nashville Peach Pickers

Nashville Peach Pickers  Ordnance Plant Workers

Ordnance Plant Workers  Ozark REA Plant

Ozark REA Plant  Riceland Foods Facility

Riceland Foods Facility  Rogers Broiler Show

Rogers Broiler Show  Salt Kettle

Salt Kettle  Security Bank

Security Bank  Smackover Oil Field

Smackover Oil Field  Southern Mercantile Store

Southern Mercantile Store  St. Paul: Railroad Timber

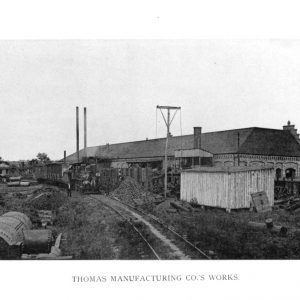

St. Paul: Railroad Timber  Thomas Manufacturing

Thomas Manufacturing  Timber Cutting

Timber Cutting  Turrentine Hotel

Turrentine Hotel  Don Tyson

Don Tyson  First Opening of Wal-Mart

First Opening of Wal-Mart  Waldron Western Auto Store

Waldron Western Auto Store  White Hall: Lock & Dam No. 5

White Hall: Lock & Dam No. 5  William Woodruff

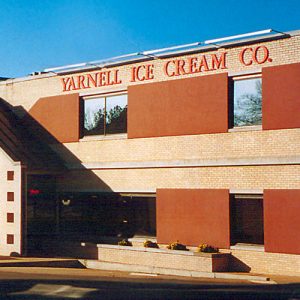

William Woodruff  Yarnell Ice Cream Company

Yarnell Ice Cream Company  Yarnell Ice Cream Company

Yarnell Ice Cream Company

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.