calsfoundation@cals.org

Salt Making

Salt making was an enterprise carried out in Arkansas for more than 600 years, first by the prehistoric Native Americans, who began to make salt around AD 1400, during the time in which they adopted a diet rich in corn and other domesticated plants. Salt was desirable for flavoring stews and other corn dishes, and it was an important nutrient for people living in a hot climate. It may have had a number of other uses, including for rituals, but it was not commonly used by Indians then to salt meat in much the same fashion that Europeans were accustomed to. European explorers and American settlers made salt for their own uses and for sale, until good quality, commercially available salt became cheap and abundant in the mid-nineteenth century. To people from Old World cultures, salt was important for human consumption, for the care of animals, and for preserving and extending the shelf life of butchered livestock and other meats, among other uses.

Underground sediments formed by ancient seas are rich in salts. In some places, this mineral can be mined as a solid. Elsewhere, as in Arkansas, groundwater passing through these sediments brings salt to the surface in liquid form as brine springs or seeps. In Arkansas, brine is most commonly found seeping into streams in two places, along the Arkansas River Valley upstream from Little Rock (Pulaski County) and in the southern part of the state.

When brine is evaporated, salts are re-crystallized and left behind. Sodium chloride, also known as table salt, is one of the salts produced by this process. The manner of evaporation varies around the world, depending on the strength of the brine and the kinds of fuel and labor available to do the work. In Arkansas, there are several locations where brine was strong enough to be converted to salt with simple technology. Wood was also available in abundance for fuel. Evidence indicates that Arkansas salt makers always used a direct method of boiling brine in large containers over wood fires to make their product.

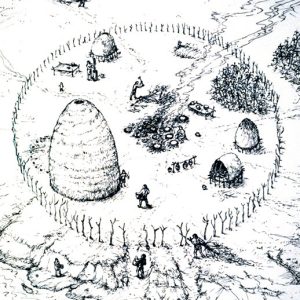

The best-known prehistoric salt-making sites are found in southwest Arkansas, although there are indications that some late prehistoric people in the Mississippi River Valley of northeast Arkansas, and people living along the Arkansas River upstream from Little Rock, made salt as well. One prehistoric Caddo salt-making settlement, the Hardman Site, situated near Arkadelphia (Clark County) in the Ouachita River valley, has been studied in detail. This site and data gathered from a few other prehistoric Caddo sites elsewhere in southwest Arkansas provide information about the manner of Indian salt making.

Some Caddo lived close to the banks of creeks and small streams where brine seeps were situated. The liquid was collected directly from the seep and transported only a short distance to the processing site. Large, thick, shallow ceramic pans—made on the site expressly for salt making—were filled with liquid while they sat on open fires or on beds of hot coals. Once the liquid was evaporated, a small amount of crystallized salt could be scraped out of the pan, and the pan was then re-used. Trees were cut and chopped into manageable pieces with stone axes for wood to fuel the fires.

It is likely that not all liquid was evaporated before the still-wet salt was collected and packed into thinner ceramic jars and other containers to air-dry into solid cakes in a shelter or storage building. This would speed up the process, save on fuel, and create a convenient, transportable package. The solid cakes were subsequently released by breaking the outer container. These relatively small blocks of salt could be transported from place to place on foot or in canoes and would remain solid for a long time, while small pieces were broken off for daily use.

Salt making appeared to have been a special but part-time activity for the prehistoric Caddo who lived near brine seeps. The other activities of normal daily life— such as tending gardens, hunting, and making and repairing houses—took place at the same location. It is possible that, for some Caddo, salt making was an inherited family tradition. Spanish explorers in the Hernando de Soto expedition temporarily appropriated some of these brine seeps to make salt during their trek across south Arkansas. One such location was probably in the vicinity of Arkadelphia in the Ouachita River valley.

When French settlers arrived in Louisiana in 1700, the Caddo of Arkansas and Louisiana were still well-known salt makers, and they were among the Indians who traded salt to both Indians and Europeans throughout the Mississippi Valley. For a while, salt was one of the commodities that European settlers had to acquire from Indian traders, as shipments from elsewhere were few and unreliable. Hunters and trappers periodically made small amounts of salt for their own use at brine seeps that they encountered during their travels. As Indian populations declined through disease and warfare and relocated their communities to new locations, people of European descent had greater access to salt-making sites.

After the Louisiana Purchase, Americans were eager to obtain access to brine seeps, given that salt was a valuable commodity. Realizing this importance, the government established a policy to remove land with salines from public sale, instead leasing the springs to prospective salt makers. Issues arising out of the control, ownership, and use of salines were frequent items of concern in territorial and national politics.

Frontier salt makers used large cast iron kettles, obtained from eastern manufacturers, in which they boiled brine. In order to obtain enough concentrated liquid, they often dug wells to tap underground sources. Kettles rested on brick or stone rubble furnaces, sometimes with chimney flues, in frame sheds that protected the furnaces from the weather. Timber was used for fuel, and these enterprises needed access to large tracts of woodland to be successful. Wet salt was piled in a separate building to dry, then was sacked or packed into barrels for shipment to markets. Some people bought personal supplies directly at local salt works.

The best-known salt works serving territorial Arkansas was on the Illinois River in what is now eastern Oklahoma, not far from Fort Smith (Sebastian County). It was situated in the Lovely’s Purchase section of Cherokee lands and was one source of contention regarding Cherokee land boundaries and treaty rights between 1817 and 1828. For most of this time, two white men, the brothers Mark and Richard Bean, held leases and gradually developed a salt-making facility that served Fort Smith, settlers in the Arkansas River Valley, and more distant settlements in Arkansas. Several other local salt makers provided their product on a small scale for settlers elsewhere in Arkansas, notably in the Ouachita valley near modern Arkadelphia and in the Little and Rolling Fork river valleys in southwest Arkansas.

In 1828, a treaty gave control of the salines around the Bean salt works to the Cherokee, and white settlers were ordered to leave Cherokee lands. The salt works operating in Arkansas were relatively unproductive for a variety of reasons, including disputes over rights to salines and neighboring timberlands, as well as the limited quantities of concentrated brine. Settlers depended increasingly on commercial salt bought from sources outside Arkansas until the outbreak of the Civil War. When outside market sources were lost during the war, several Arkansas salines were reopened temporarily to meet local demands and military needs. Salt making ceased in Arkansas shortly after the war, when abundant and relatively cheap salt was once again available from other sources.

For additional information:

Brown, Ian W. Salt and the Eastern North American Indian: An Archaeological Study. Lower Mississippi Survey Bulletin No. 6. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography, Harvard University, 1980.

Dumas, Ashley A., and Paul N. Eubanks, eds. Salt in Eastern North America and the Caribbean: History and Archaeology. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2021.

Early, Ann M., ed. Caddoan Saltmakers in the Ouachita Valley: The Hardman Site. Research Series No. 43. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 1993.

Littlefield Jr., Daniel F. “The Salt Industry in Arkansas Territory, 1819–1836.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 32 (Winter 1973): 312–336.

Lonn, Ella. Salt as a Factor in the Confederacy. Southern Historical Publications No. 4. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1965.

Stroud, Raymond B., Robert H. Arndt, Frank B. Fulkerson, and W. G. Diamond. Mineral Resources and Industries in Arkansas. Bulletin 645. Washington DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Mines, 1969.

Ann M. Early

Arkansas Archeological Survey

Hardman Site

Hardman Site  Salt Kettle

Salt Kettle  Salt Kettle

Salt Kettle

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.